Abstract

Objective

To compare the voice onset time (VOT) differences of Korean stops in the initial and intervocalic positions between the aphasic patients with peculiarities of aspiration and a control group.

Method

We examined 15 aphasic patients (nine males, six females) who had suffered a stroke (average age 49.7 years) and 15 healthy controls (average age 47.4 years). An aphasia examination was made by an aphasia battery of three standard tests and VOT was analyzed instrumentally. Stop consonants in the initial and intervocalic position were measured to categorize them according to aphasia types, place of articulation, and manner of articulation.

Results

VOT of the aphasic patients with peculiarities of aspiration had a greater difference than that of the controls, indicating that the temporal non-coordination between the laryngeal adjustment and oral articulators of aphasic patients happens due to the VOT of stops in the initial and intervocalic positions (p<0.05).

Conclusion

VOT of stop consonants in the initial position produced by aphasic patients tends to be proportional to their breathing. It can cause glottal width and make aphasic patients' VOT duration longer. Lastly, the method to measure the VOT of aphasic patients is more significant for the types of phonation than for the places of articulation, and makes it possible to induce abnormal VOT.

Aphasia is a partial or general disorder of recognition systems and other communication mechanisms, which are the basis of language patterns and language itself, and which is due to damage to the speech portion of the central nervous system, and it is often defined as the neurological disability to understand or form language.1 Also, the language disorder of aphasic patients can be categorized in two ways: typological, in which one or more aspects of language understanding, where the output of aphasia patients is invaded, and non-typolo gical, in which all other aspects of language understanding and output have been damaged.2 However, there can be some cases where this definition might not be limited to language and the cognitive process or the domain of language.3

Generally, a language disorder from cerebral damage is termed 'aphasia' and a speech sound disorder is termed 'dysarthria'. For several decades, cerebral neurologists, psychologists, and linguists have studied mainly aphasia lan guage disorder. Recent advances phonology and sound analysis equipment have enabled the study of dysar thria, which occurs when aphasia patients speak. In the phonological field,4 phonological codes or damage to work memory have been intensively studied, while the voice onset time (VOT) of aphasic patients and the length of vowels and syllables have been studied and compared with a control group in the field of acoustics.5 The study of temporal abnormalities,6 especially those related to VOT and the length of syllables of aphasic patients, has contributed to the study of damage to language or word exercise plans, or the apraxia func tion, and the evaluative study of time coordination7 bet ween larynx and oral articulating organs. It also has emphasized the importance of articulation places and the output of the voiced and voiceless consonants of stop con sonants.8 Such studies make it possible to expand the range of interpretation for the speech evaluation of apha sia patients, and VOT studies can be understood as extensive, involving speech exercise plans and apraxia function.

VOT has been used as a phonological clue or index for the study of interaction between articulating exercises and laryngeal adjustment. Thus, this study aimed to address the hypothesis that, in the Korean language, the phonological characteristics of consonants rather than those of vowels are more focused because the VOT shows the degree of aspiration better in the beginning of the speech when the stop sounds are articulated, and is used as a main measure in light of the fact that it can show phonological difference according to the places of consonants and the types of phonation. Also, to analyze whether there is any difference in phonetic processes according to articulation places phonologically, the output of voiced and voiceless consonants was analyzed according to the articulation sites, and the sound spectral time of the phonetic environment was compared and evaluated, to be used as the baseline data for the evaluation and diagnosis of aphasic patients.

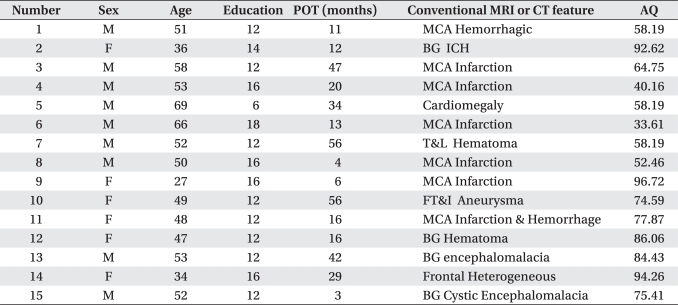

Subjects were 15 aphasic patients (nine males and six females) who were diagnosed with cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral hematoma, and/or aneurysm-related diagnosis from the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Chonbuk National University, between August 20, 2008 and February 28, 2009. Their average age was 49.7±11.02 years (Table 1). When evaluated, they had no sensitivity problems and were right-handers before they were diagnosed. Subjects of the control group were similar to the patients in their age (47.4±8.24), sex, dialects, and right-handedness. They had no problems with their hearing and language use, and did not have any anatomical drug problems either.

To evaluate their aphasia, the Chonbuk National University Aphasia Battery (CNUAB) was used. The battery is comprised of three test kits: Japanese Standard Language Test of Aphasia,9 the Minnesota Test for Differential Diagnosis of Aphasia,10 and the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination.11

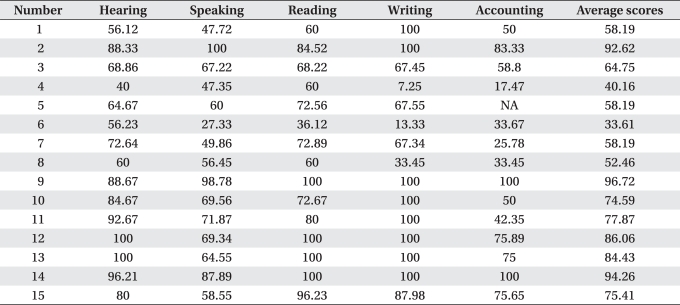

Table 2 shows the test scores for the language evaluation of the experimental group.

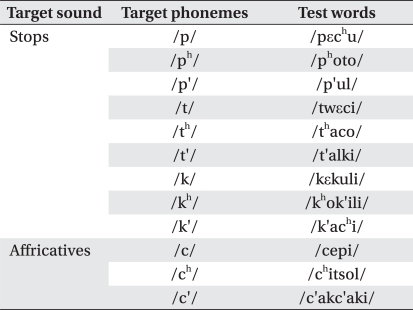

Evaluation of the articulation disorder of the aphasia patients was done using the words of the VPI Articulation Differential Examination kit,12 with single- or multi-syllable words made up of CV (con sonant vowel) or CVC (C: stop sound) types, which have meaning (Table 3). As subjects of the experimental group could read colloquial language, they were asked to read the cards on which pictures and words were provided together. If they could not respond within 15 seconds, they were given oral stimulus. The voice files of the subjects were stored and analyzed using the Computerized Speech Lab Model 4500 KayPentax (Montvale, NJ, USA). The sampling rate of the voice files was 11,025 Hz, which operated at 100 points (161.50 Hz) above the Nyquest Frequency. The VOT was analyzed on the broadband spectrum.

For statistical analysis, SPSS version 14.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used to discriminate the significance using one-way ANOVA analysis independent samples, t-test mean comparison on the voiced and voiceless according to the places of articulation, types of phonation, and the places of articulation in the intervocalic VCV combinations. To verify the identity of the variance of the two groups, it was statistically analyzed by f value. The quantitative evaluation of the VOT category was done based on the previous research methods which used the comparison of mean difference.

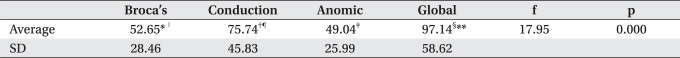

After testing the aphasic patients, differential and variance analyses of the results were done and compared with the results of the control group. In the differential analysis of the VOT length according to aphasia types, the length of the VOT was the shortest in ano mic aphasic patients (49.04 ms) and there was no significant difference with the control group, yet all the other patients revealed significant differences (p<0.05). In addition, the length of the VOT and vowels of the experimental group were longer compared with the results of the control group, which was consistent with the results of the previous study.13

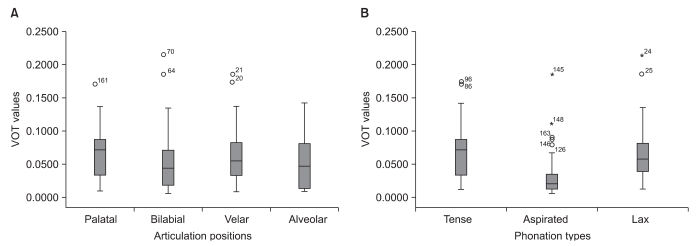

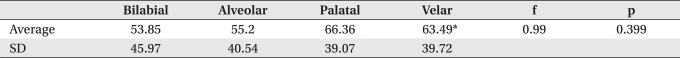

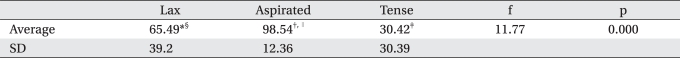

Based on the study results show that VOT closely related with aspiration degree and that this is related to the length of the VOT, we compared the VOT difference with aphasic patients who displayed aspiration according to the articulation places and phonation types. While the vocal cords remained distant during the lead time, aphasic patients revealed differences in phonation types (Table 4) rather than in articulation sites (Table 5).

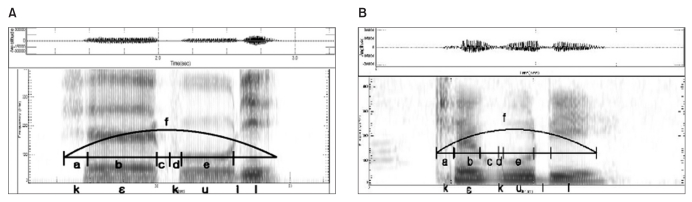

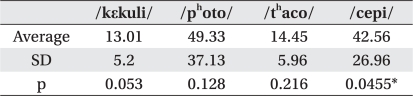

To observe voicing phenomenon, the voicing errors and voice lead times of aphasic patients with pronounced aspiration were analyzed. When they were analyzed on the spectrogram with four voiced words (/kεkuli/, /photo/, /thaco/, /cepi/) according to the articulation places, only the bilabial sounds showed significant differences (p<0.05) and the lead time was long (Fig. 1-A , 1-B) in differential analysis with the control group (Table 5).

VOT had a close relationship with the degrees of aspiration or glottal width, and all types of aphasic patients revealed significant differences in VOT compared with the control group (Table 6). Also, the length of VOT was related with the aspiration, as evidenced by significant differences articulating the aspirated normal sound and aspiration (Table 4). In other words, the noise interval can be understood as a voice lag until the vowel formant is observed after the vertical spike on the spectrogram, which is observed due to the opening of the stop sound that is located at the word-initial. In addition, the finding that the length of the VOT of aphasic patients was longer than that of the normal control group indicated that the sound timing could vary relating to the lead time between abnormal or vocal abduction and oral plosive, owing to non-coordination between larynx and oral articulating organs, due to the turbulence which is formed at larynx.14 These results are likely attributable to an inelastic stiffness of the larynx and the loss of exercise due to the damage to the central nervous system and cranial nerves,15 so the VOT differences arise according to the degree of damage to the interaction between the tongue, pharynx, and larynx, which are related with stop sounds.

As word-initial stop sounds come out as either white or short noise intervals on the spectrogram, owing to a lack of energy because of their articulating characteristics, there could not be any information found to notify the articulating places. However, according to the VOT length, types of phonation can be categorized into normal, aspirated, or fortis sounds. One thing that could be understood is that there was a difference according to the degrees of VOT aspiration at word-initial of aphasic patients (Table 4, Fig. 2-A), confirming that the phonation type analysis of the VOT of aphasic patients with more degrees of aspiration is more significant than that of the articulating sites.

The experimental group was asked to speak normal Korean sounds that consisted of phonologically consonants. When the 15 patients of the experimental group were asked to speak four VCV words, each to find out the articulating positions, 58% (35/60) of the words were uttered as consonants, and bilabial and velar sounds showed differences with the control group in lead time (Table 7).

According to a prior study16 on the phonological aspects, some studies have indicated that words uttered as voiced or voiceless depend on the speaker's phonation speed or phonological environment, but in the case of aphasic patients they showed different results from those of the control group in voicing errors and the lead time of intervocalic VCV. However, sometimes lead time and the vowel length before the consonant stop sound are often measured and compared because it is not always true that all aphasic patients make voicing errors. As seen in Fig. 1-A and 1-B, the c interval was long as the lead time in aphasic patients and the vowel length is also shown long, consistent with previous studies.17,18 Some studies have assumed that the output difference of voiced · unvo iced consonants of aphasic patients are the interaction between the muscles of arytenoids cartilage and posterior cricoarytenoid cartilage, which are known to control the distinction of the voiced and voiceless consonants.19

Although the normal sound of VCV has a small amount of aspiration, the vocal cord's vibration interval (d) in aphasic patients turns out long, which means that there could be a temporal non-coordination between the larynx and the oral articulating organs, not only at the word-initial, but also at the intervocalic VCV. This should be examined more widely in more subjects.

This study was performed to find out the temporal abnormalities of aphasic patients. Their VOT was measured using word-initial stop consonants to provide differential analysis according to the places of articulation and the types of phonation, as well as measuring the differential analysis of voicing errors and lead time in intervocalic VCV (C: stop consonant) combination.

The research results show that since the word-initial VOT of aphasic patients is proportional to the degrees of aspiration, VOT could be much better analyzed by the types of phonation than at the places of articulation, and there is a significant difference from normal people. In the analysis of the output of voiced · voiceless consonants of aphasic patients, more than half (approximately 58%) of the aphasic subjects showed voicing errors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A091220).

References

1. Rosenbek JC, LaPointe LL, Wertz RT. Aphasia: a clinical approach. 1989. 1st ed. Boston: Pro-Ed.

2. Hegde MN. A coursebook on aphasia and other neu rogenic language disorders. 1994. 2nd ed. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group.

3. Brookshire RH. Introduction to neurogenic communication disorders. 2007. 7th ed. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier.

4. Caplan D, Futter C. Assignment of thematic roles to nouns in sentence comprehension by an agrammatic patient. Brain Lang. 1986; 27:117–134. PMID: 3947937.

5. Kent RD, Kent JF, Rosenbek JC. Maximum performance tests of speech production. J Speech Hear Disord. 1987; 52:367–387. PMID: 3312817.

6. Koenig LL. Distributional characteristics of VOT in children's voiceless aspirated stops and interpretation of developmental trends. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001; 44:1058–1068. PMID: 11708527.

7. Adams SG, Weismer G, Kent RD. Speaking rate and speech movement velocity profiles. J Speech Hear Res. 1993; 36:41–54. PMID: 8450664.

8. Grigos MI, Saxman JH, Gordon AM. Speech motor development during acquisition of the voicing contrast. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005; 48:739–752. PMID: 16378470.

9. Japan society of high tea brain. Standard Language Test of Aphasia. 2003. Tokyo: Sinheunh Medical Press.

10. Schuell H. Differential diagnosis of aphasia with the minnesoto test. 1997. Minnesota: University of Minnesota.

11. Goodglass H, Kaplan E, Barresi B. Boston diagnostic aphasia examination. 2000. 3nd ed. Pennsylvania: Penny-Lea&Febiger.

12. Kim HG, Shin HK. VPI Articulation differential examination. 2001. Jeonju: Research Institute of Speech Science Press.

13. Grigos MI. Changes in articulator movement variability during phonemic development : a longitudinal study. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009; 52:164–177. PMID: 18664683.

14. Klatt DH. Voice onset time, frication, and aspiration in word-initial consonant clusters. J Speech Hear Res. 1975; 18:686–706. PMID: 1207100.

15. Weismer G. Philosophy of research in motor speech disorders. Clin Linguist Phon. 2006; 20:315–349. PMID: 16728332.

16. Koenig LL. Distributional characteristics of VOT in children's voiceless aspirated stops and interpretation of developmental trends. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001; 44:1058–1068. PMID: 11708527.

17. Lofqvist A. Acoustic and aerodynamic effects of intera rticulator timing in voiceless consonants. Lang Speech. 1992; 35:15–28. PMID: 1287385.

18. Zlatin MA, Koenigsknecht RA. Development of the voicing contrast: a comparison of voice onset time in stop perception and production. J Speech Hear Res. 1976; 19:93–111. PMID: 1271805.

19. Baum SR, Blumstein SE, Naeser MA, Palumbo CL. Temporal dimensions of consonant and vowel production: an acoustic and CT scan analysis of aphasia speech. Brain Lang. 1990; 39:33–56. PMID: 2207620.

Fig. 1

Relative comparison of VOT, VD duration and lead time between aphasic patients (A) and normal controls (B). These figures indicate that VOT, VD duration and lead time of aphasic patient are longer than those of normal control (VD: vowel duration, a: initial VOT, b: initial vowel duration, c: hold, d: lead time, e: second vowel duration, f: total duration).

Fig. 2

Comparison of (A) phonation types and (B) articulation positions. Phonation types were significantly showed differences than articulation positions compared with normal control group.

Table 5

VOT ANOVA of Articulation Positions and the VOT t-test of Aphasic Patients and Control Groups

Table 6

VOT ANOVA of Aphasia Types and the VOT t-test of Aphasic Patients and Control Groups

ANOVA: Analysis of variance, SD: Standard deviation

*p<0.05, compared to conduction, p<0.01, compared to global, †p<0.05, compared to Broca's, p<0.01, compared to anomic, ‡p<0.01, compared to conduction, p<0.01, compared to global, §p<0.01, compared to Broca's, p<0.01, compared to anomic, ∥,¶p<0.01, by t-test to control group, **p<0.05, by t-test to control group

Unit: ms

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download