INTRODUCTION

Pheochromocytomas (PCC) and paragangliomas (PGL) are rare chromaffin cell-derived neuroendocrine tumors of the adrenal medulla and extraadrenal paraganglia, respectively. The incidence of PCC/PGL is estimated between 2 and 5 patients per million per year [

1] while the prevalence in hypertensive patients is between 0.2% and 0.6% [

2]. Within this group of tumors, PCC make up 85% of the cases while 15%–20% are PGL [

3]. PGL can be derived from either the parasympathetic or sympathetic nervous system. Parasympathetic PGL are usually located in the head and neck region and these tumors are rarely functional (<5%) [

45]. Abdominal PGL, on the other hand, are predominantly sympathetic in origin and are located in the paraaortic and paracaval areas and around the inferior mesenteric artery and aortic bifurcation [

4]. Some are also found in the duodenum, bladder, and spine. Abdominal PGL can produce, store and/or secrete catecholamines and their metabolites and produce the classic symptoms and signs of hypertension, palpitation, dizziness, anxiety, flushing, headache, and diaphoresis due to catecholamine surges. The hypertensive episodes and symptoms are usually paroxysmal in nature; hence, diagnosis may not be apparent for years as a result.

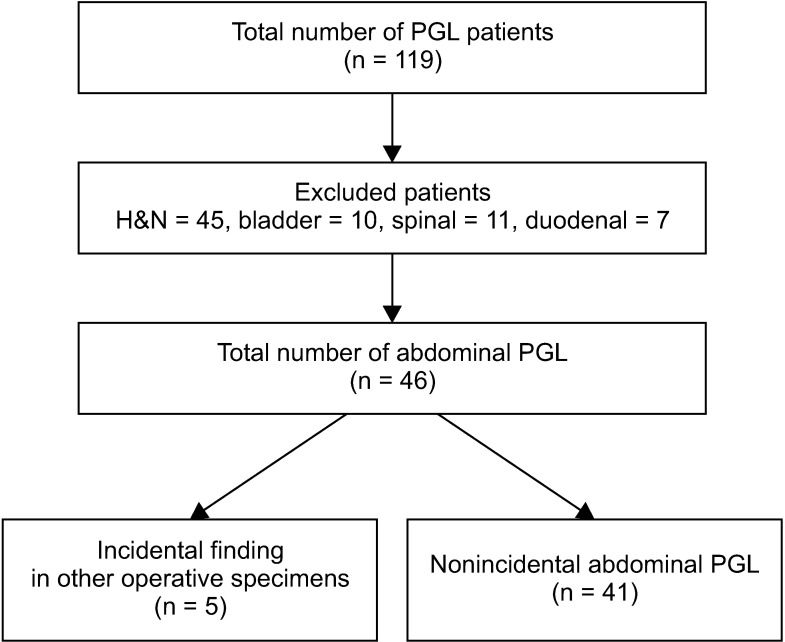

The rarity of abdominal PGL has limited the number of publications on this subject and most are case reports and literature reviews. Many series include both PCC and PGL in their reports. We, therefore, aim to analyze our data of PGL on its own and report our experience in managing this rare condition over the last decade at Severance Hospital, a tertiary referral center for endocrine surgery in Seoul.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

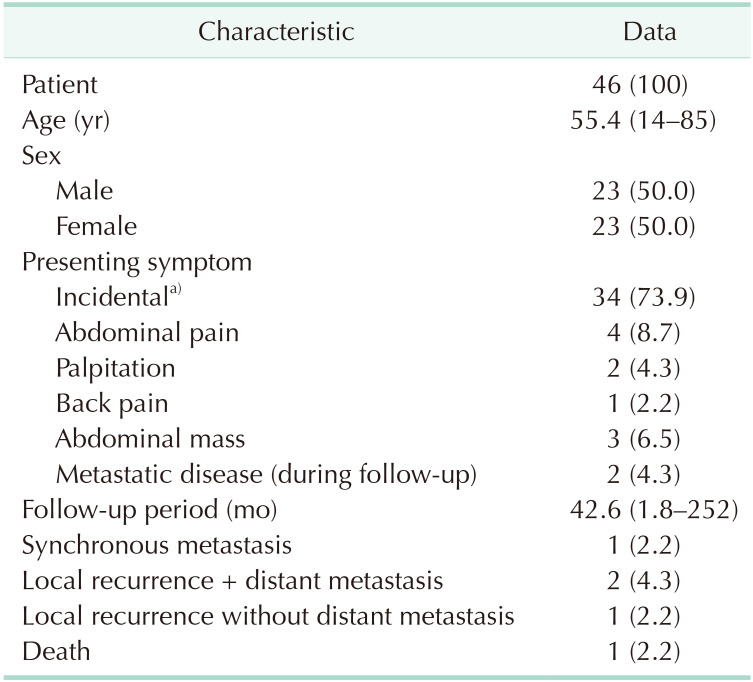

Abdominal PGL are rare tumors, highlighted by the fact that only 46 patients were treated at our hospital over the last decade, despite our hospital being a large tertiary referral center for endocrine surgery. Our results are consistent with other published data with regard to the roughly equal sex distribution [

167] and the mean age of diagnosis in the 5th decade, particularly in the sporadic form of the disease [

3].

The classic presentation of PCC/PGL is related to intermittent surges of catecholamine resulting in symptoms such as palpitation, headache, and flushing. However, contrary to other publications [

3], our patients mostly presented incidentally. This could be related to the high rates of CT scans performed as part of health screening in South Korea. Though imaging modalities become more sophisticated and cheaper to obtain, the pattern of presentation would become increasingly incidental rather than symptom related. This trend is not unique to PGL, but also all other medical conditions.

According to the Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines on management of pheochromocytomas and PGL published in 2014 [

2], the initial testing for PCC/PGL should include plasma free metanephrines or urinary fractionated metanephrines. Unfortunately, in our patient population, only 18 patients had these blood tests done. The reason for this is not very clear from the medical records, but we presume that the tests were not performed because not all patients were managed by an endocrinology team and many of the patients did not present with the classic symptoms. Fortunately, this did not result in any adverse outcome in terms of blood pressure management perioperatively. This highlights that a strong clinical suspicion of PGL should be present when dealing with retroperitoneal tumors located close to the midline in the abdomen, regardless of whether the classic symptoms are present.

The location of PGL close to or at the midline is due to its origin, being derived from the sympathetic chain in the abdomen and pelvis. Our patients predominantly had tumors located to the left of midline, which is similar to other studies [

78]. This is, however, not a regularly reported finding, and the laterality of PGL is still equivocal.

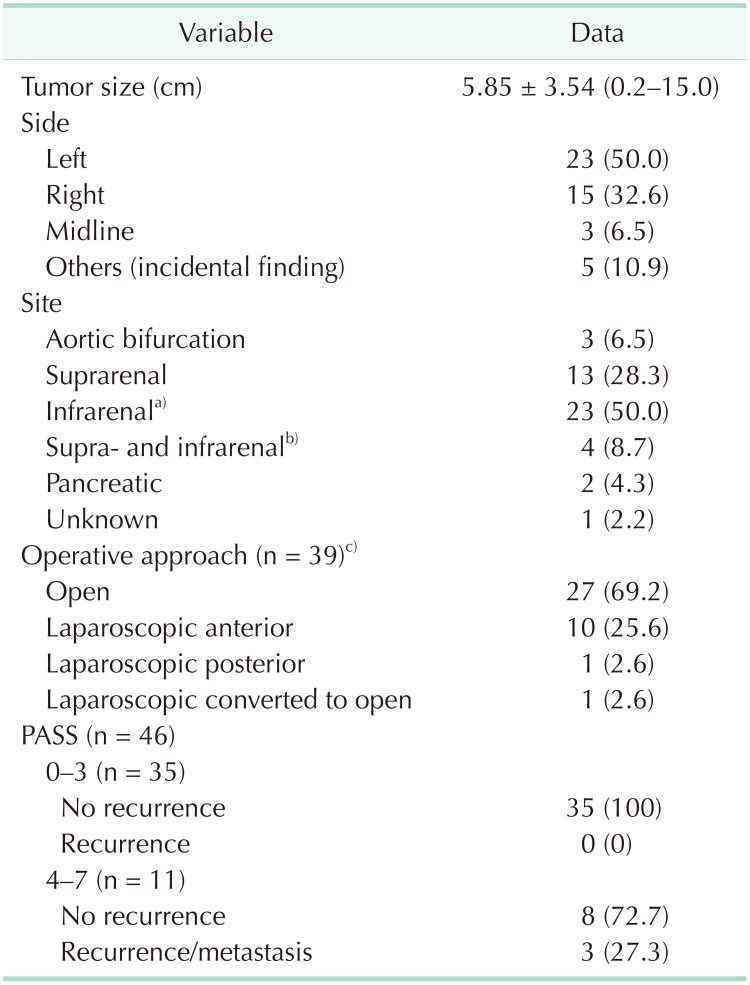

The surgical approach of PGL is quite variable depending on the size, location, suspicion of malignancy, and surgeon skill. In our study, most operations were performed with the open approach, followed by the laparoscopic transperitoneal anterior approach. All tumors less than 7 cm were resected with the open approach apart from one 10-cm tumor which was resected with the laparoscopic anterior approach. The reason for the higher open approach as opposed to a minimally invasive technique could be because referrals in our hospital are made to surgeons from different specialties such as endocrine surgeons, hepatobiliary surgeons, and urologists, depending on the location of the tumors rather than a streamlined referral to 1 specialty. With the smaller number of cases per surgeon, many surgeons would have felt more comfortable approaching these tumors via the open technique as the locations of these tumors can be very challenging. The most difficult tumors would be large tumors located in the aortocaval space and those adherent to or encasing major vessels such as the aorta, inferior vena cava, and renal vessels. However, as surgeons become more comfortable with laparoscopic transperitoneal or retroperitoneal adrenal surgeries, small PGL can be safely resected with minimally invasive techniques [

89101112]. The retroperitoneal approach also has the added advantage of not entering the peritoneal space hence reducing the potential injury to adjacent organs such as the liver, duodenum, stomach, spleen, and pancreas. This approach is also useful in patients who have had previous abdominal surgeries, and hence abdominal adhesions.

The pathological diagnosis of PGL is made in the presence of the classic feature of cell nests arranged in the Zellballen pattern separated by fibrovascular stroma and surrounded by sustentacular cells. The cells are typically polygonal or oval-shaped and stain positive for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and CD56. Sustentacular cells are usually S100 positive [

1314]. To differentiate it from other neural origin tumors, PGL usually stain negative for MelanA, inhibin, keratin, and calretinin. On the other hand, the diagnosis of malignancy cannot be made based on any one or more histopathological criteria alone. Malignancy is defined as the presence of tumors in sites that do not usually contain chromaffin cells, i.e., evidence of metastasis [

4]. Several scoring systems have identified factors that increase the risk of malignancy. One such scoring system is the PASS which was developed by Thompson [

14] in 2002. This score has been widely used internationally, including in our hospital. Thompson proposed that a score of ≥4 increases a patient's risk of developing metastasis. In our cohort of patients, all patients with metastasis and/or local recurrence had PASS of ≥4. However, not all patients with scores of ≥4 recurred. This is consistent with Thompson's study where 17 out of 50 patients who had histologically “malignant” features had not developed clinical metastasis during his study period [

14]. Other authors have also not been able to validate the accuracy of PASS [

1516]. The other scoring system in use currently is the Grading System for Adrenal Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma (GAPP), proposed by Kimura et al. [

17] in 2014. The main difference between GAPP and PASS is the inclusion of the type of catecholamine secreted by the tumor and the Ki67 index. Only norepinephrine secretion scores a point, while nonfunctioning and epinephrine secreting tumors have zero scores. However, because this is a relatively new scoring system, the GAPP scores have not been reported by our pathologists. This scoring system, however, has been validated by Koh et al. [

16] in 2017, and these authors have also included mutation in the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) type B to obtain a modified GAPP score, which was predictive of metastasis.

In our patient population, the mean follow-up period was 42.6 months, with the longest follow-up period of 252 months in a patient with local and distant recurrence after 19 years. This patient is still alive with the disease after 21 years. The other 2 recurrences occurred 2 and 3 years after their initial diagnoses. This demonstrates the highly variable disease pattern, with recurrence possible decades after the initial diagnosis. The disease-specific mortality is also low, with only 1 death reported out of a total of 46 patients over the 11.5 years of the study period.

The limitation of this study is its retrospective design. The most significant omission is the genetic profile of patients, as up to 60% of PCC/PGL cases may have a germline or somatic mutation [

1]. Associated mutations are located in the von Hippel Lindau (

VHL), SDH complex (

SDHx:

SDHA,

SDHB,

SDHC, and

SDHD;

SDH5/

SDHAF2), neurofibromin 1 (

NF1), rearranged during transfection photo oncogene (

RET), transmembrane protein 127 (

TMEM 127), Myc associated factor X (

MAX), and menin (

MEN1) genes [

125]. Mutation in the

SDHB gene has been linked to high rates of malignancy of 40% or more [

2]. Large prospective studies investigating the link between genetic mutation and long-term survival and recurrence would be useful to risk stratify patients and tailor the intensity of followup for patients.

Abdominal PGL are rare tumors with excellent prognosis. However, given that recurrence can occur more than a decade after diagnosis, long-term follow-up is essential, especially for patients with PASS of ≥4.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download