INTRODUCTION

Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is one of the most challenging abdominal surgeries, which requires complicated anastomosis. Since Whipple reported the first one-stage operation for complete excision of the head of the pancreas and the entire duodenum in 1940, the surgical techniques and postoperative managements have constantly evolved over the decades [

1]. Nowadays, the safety of this operation has improved; its morbidity and mortality rates have been lowered to 18%–43% and 1%–2.3%, respectively [

234].

Recently, the surgical outcomes and long-term prognosis in patients with gastric cancer have improved due to the development of imaging modalities, surgical techniques, and the regimens of adjuvant chemotherapy [

5678]. Most patients with gastric cancers have frequent postoperative follow-up every 3 or 6 months using various high-resolution imaging modalities, including CT and/or MRI. Therefore, the detection rates of the pancreatobiliary lesions in patients who underwent previous gastrectomy have increased [

910].

Despite the difficulties mentioned above, PDs are being performed in patients with a history of gastrectomy. However, little is known about the clinical outcomes of the patients who underwent secondary PD after previous gastrectomy. Many studies were case series due to the difficulty in collecting a large cohort of these patients from a single institution [

11121314151617]. Although there was also one multicenter study, case number was also not large enough [

9].

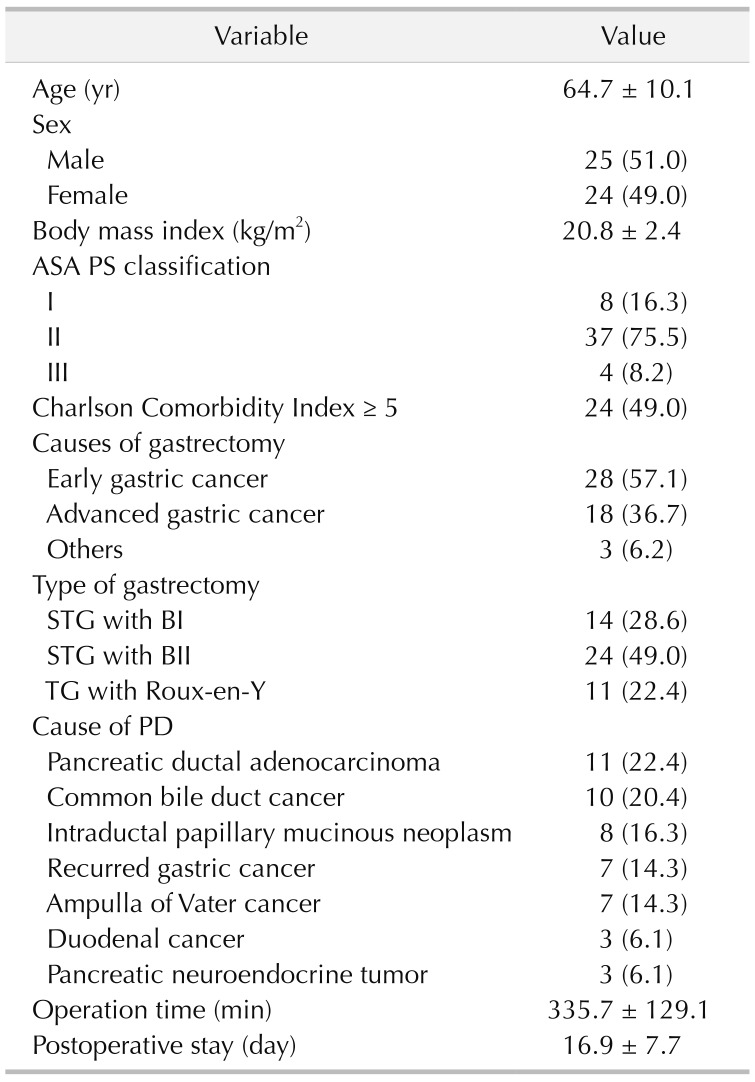

Therefore, this study was designed to analyze a relatively large number of patients who underwent secondary PD after previous subtotal or total gastrectomy (TG) in a high-volume tertiary referral center. We also evaluated the clinical outcomes of these patients and compared them with the patients who underwent conventional PD without history of previous gastrectomy using a statistical compensation method.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

PD remains one of the most challenging surgeries among abdominal surgeries. This challenging surgery can become even more complex in patients with previous operation history, especially if gastrointestinal surgery. Previous gastric surgery may alter the anatomy of the alimentary tract and cause a significant amount of adhesion around the surgical field of PD. Despite the challenges, PD after previous gastrectomy is possible and continues to be performed. However, there is only a very limited number of reports on secondary PD in patients with a history of previous gastrectomy. Most of the previous reports are case reports or case series of less than 10 patients [

111214151617]. Lee et al. [

9] reported a multicenter study about secondary PD in patients with a history of previous gastrectomy in 2017. They analyzed 39 patients and confirmed the safety and feasibility of secondary PD, based on results which were similar to those of our study.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the clinical outcomes of secondary PD after prior gastrectomy and primary conventional PD using the largest study population based on the unified surgical maneuver from a single institution.

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignancies in Asian countries, such as Korea, Japan, and China [

567]. For this reason, we are able to find the pancreatobiliary tumors in patients with a history of gastric surgery more frequently in these countries. In addition, the treatment outcome of gastric cancer has been so greatly improved that the number of gastric cancer survivors is increasing. Furthermore, because these patients receive regular follow-up using high-resolution cross-sectional imaging techniques, incidental detection of pancreatobiliary tumors is becoming more frequent nowadays [

2021]. For such reasons, confronting pancreatobiliary neoplasm in need of PD in patients who have received previous gastric surgery is not such a rare occasion today, especially in Asian countries. Therefore, surgeons need to be familiar with the operative techniques and the unique outcome of PD in these patients.

There are several challenges in performing a secondary PD in patients with previous gastrectomy. First of all, because gastric surgery, especially if it was cancer surgery, shares the operation field with PD, much adhesion is formed around the hepatoduodenal ligament, the common hepatic artery, and the anterior/superior surface of the pancreas. This results in difficulty and challenges in surgical dissection. These adhesions increase the risk of intraoperative bleeding and injury of structures and vessels in the process of dissection [

12]. Moreover, in the patients who had been suffering from complications after previous gastrectomy, the adhesions may be even more severe than expected. Therefore, very meticulous adhesiolysis and dissection are especially important in the secondary PD.

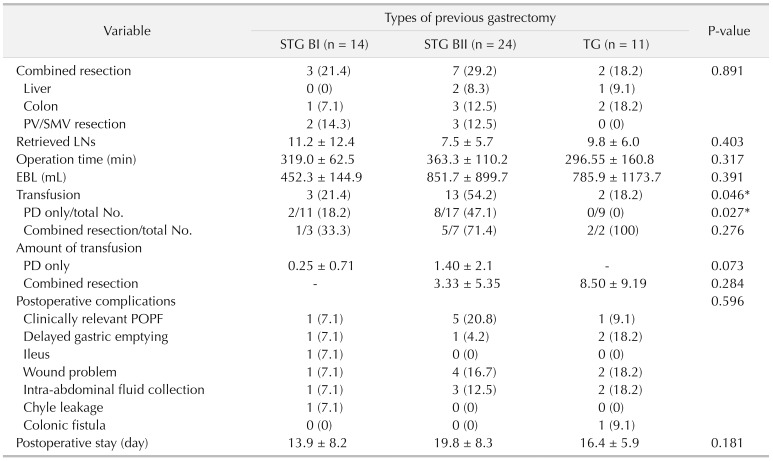

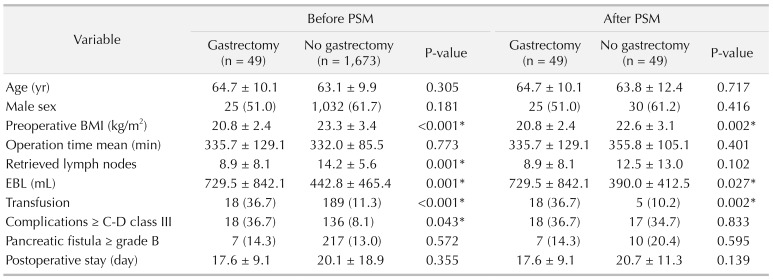

Secondly, it is difficult to perform fine LND and to retrieve a sufficient number of LNs in the secondary PD. In cases of operations for gastric cancer, the LNs around the hepatoduodenal ligament (D1+ LND) and the common hepatic artery (D2 LND) are routinely removed. This previous LND in these regions causes adhesions and fibrosis around the structures. The LND becomes very hard occasionally leading to incomplete LND, and distinguishing fibrotic tissues and lymphatic tissues becomes difficult. In this study, the mean number of retrieved LNs in the gastrectomy group was 8.9, comparable to the results of previous studies [

22]. It should be noted that the mean number of retrieved LN was significantly lower in patients with a history of previous gastrectomy in the overall analysis, although it did not show statistical differences after PSM analysis. Also, although statistical significance was not reached, the absolute number of retrieved LN was lower in patients with a history of previous gastrectomy (8.9

vs. 12.5), even in PSM analysis. This may reflect how much more effort needs to be asserted in patients with a history of previous gastrectomy to perform comparable LND with those without a history of gastrectomy, even considering that some LND was performed in the previous surgery.

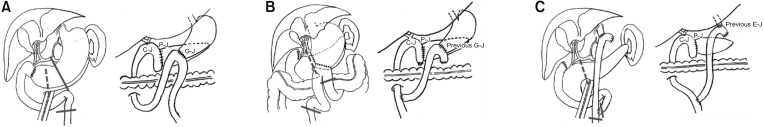

Thirdly, the altered anatomy of the alimentary tract due to previous gastric surgery makes anastomoses in secondary PD more difficult. The surgeon should recognize what type of gastrectomy was performed previously and carefully plan how the new anastomoses and reconstructions should be done. In our institution, Child method is routinely used for reconstruction, in which P-J is done at the most proximal of the jejunal stump, followed by C-J approximately 10 to 15 cm distal to P-J site, and G-J or duodenojejunostomy most distally (about 50 cm distal from C-J) [

18]. Reconstruction in STG BI is not very complicated, and similar routine anastomosis could be performed once dissection and adhesiolysis are successfully completed. More complicated reconstruction is needed for the patients who underwent either STG BII or TG than those who underwent STG BI. In both STG BII and TG, bowel continuity is altered and the adhesions around the previous bowel anastomosis may interfere with the dissection and new reconstruction [

23]. However, our experience demonstrates that it is all possible with careful dissection and planning. Although, a previous study reported some cases of postoperative afferent loop syndrome due to kinking of the small bowel, none of the patients in our study experienced such complications.

Finally, extending on the challenges inflicted by adhesion, the problems with adhesion are not only limited to the operation field of PD but applies to the whole length of the bowel. Every inch of small intestine is important. Perforations or small intestine segmental ischemia during adhesiolysis or dissection may make the planned reconstruction impossible if caused on a critical area. The surgeon may have to alter the plan and improvise with whatever remains available. This may lead to possible postoperative complications such as leakage or perforations. If very unfortunate, reconstruction may not be at all possible. To avoid unnecessary bowel injury, entire bowel evaluation should not be insisted on if there are severe adhesions, as long as bowel continuity can be inferred.

Through this analysis, we found that secondary PD after previous gastrectomy is characterized by lower preoperative BMI, higher EBL and rate of transfusion compared to conventional PD. After PSM analysis, there were no significant differences in postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo classification ≥ III) according to the presence of history of prior gastrectomy. The operation time, frequency of clinically relevant POPF, and duration of postoperative hospital stay were also comparable in the 2 groups.

Current study is limited due to its retrospective nature; however, the nature of the population makes a prospective design difficult, and compensation for the shortcomings of retrospective PSM analysis was additionally performed. Another limitation may be the focus on the surgical techniques and short-term surgical outcomes and no long-term results.

In summary, performing secondary PD in patients with a history of gastrectomy is more likely to have bleeding or transfusion; however, there are no significant differences in the actual quality of surgery, postoperative course, and short-term clinical outcomes. Multicenter studies with a larger population are needed in the future to evaluate the oncologic outcomes and establish proper treatment guidelines for patients who require secondary PD after previous gastrectomy.

In conclusion, this study showed that patients who underwent PD after gastrectomy had a lower preoperative BMI, greater blood loss during surgery, and higher transfusion rates than those who underwent conventional PD. However, there were no differences in postoperative clinical courses, including complication rates, clinically relevant POPF and delayed gastric emptying, and hospital stay. This demonstrates that secondary PD after previous gastrectomy is safe and feasible when performed by experienced surgeons, but requires high caution and meticulous skills.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download