Abstract

Purpose

Inguinal hernia repair is one of the most common treatments worldwide, but there are few studies about the use of mesh in late adolescent patients because hernias are rare in this group. This study aimed to evaluate the postoperative outcomes of hernia repair with and without mesh in late adolescent patients.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the data of 243 male patients aged between 18 and 21 years who underwent inguinal hernia repair at a single institution from January 2013 to December 2017. We distinguished 2 groups depending on the repair method; mesh (n = 121) and no-mesh (n = 122) groups. We compared the baseline characteristics, immediate postoperative outcomes, and recurrence and chronic pain rates between the 2 groups.

Results

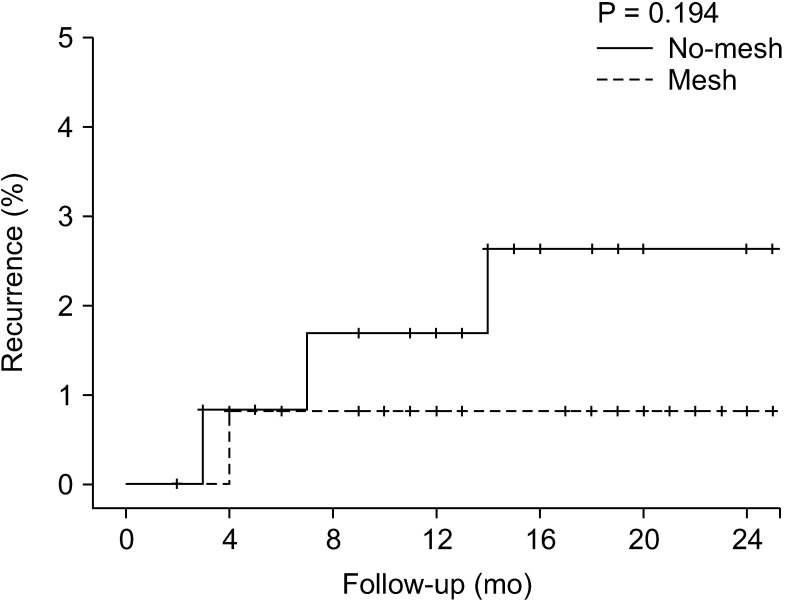

There were no significant differences between the mesh and no-mesh groups on immediate postoperative outcomes (length of stay: 18.5 ± 8.9 days vs. 17.0 ± 6.0 days, P = 0.139; postoperative complications: 8.2% vs. 6.6%, P = 0.821) and 2-year recurrence rate (0.8% vs. 2.6%, P = 0.194). There was a significant difference in the chronic pain rate (9.0% vs. 1.7%, P = 0.023).

Go to :

Inguinal hernia is one of the most common diseases worldwide. More than 20 million people undergo hernia repair surgery annually [1]. The incidence of inguinal hernia has a bimodal distribution with peaks in early childhood and old age [2]. The reason for the bimodal distribution is the different etiologies of inguinal hernia across the lifespan. Most of the pediatric inguinal hernias are congenital and indirect as they result from a patent processus vaginalis [3]. However, the frequency of inguinal hernia increases with aging, and most of them are acquired [4].

There are various methods for the surgical repair of inguinal hernias that differ in the operative tools, usage of mesh, surgical approach, and further aspects. Therefore, surgeons choose the optimal surgical technique after assessing the individual characteristics of a patient [5]. Among patient factors, age is a major aspect when deciding on the best method. Several guidelines recommend considering the use of a mesh for inguinal hernia repair according to the age of the patient [5678]. While surgeons commonly use mesh in adults, they rarely use it in pediatric patients out of concern about the potential long-term sequelae resulting from the body's inflammatory response to the mesh material [9].

However, there is currently no consensus about the usage of mesh in late adolescence who are “between” pediatric and adult patients. One reason for this is the low prevalence of inguinal hernia repair in adolescents [2]. Although there were a few studies that included young patients, they either enrolled patients whose age was up to 30 years or showed an imbalance in the age distribution [1011]. Thus far, there is no evidence on the impact of mesh on inguinal hernia repair outcomes in adolescent patients. Therefore, the preferred surgical method for adolescent inguinal hernia repair differs considerably between pediatric and general surgeons [12].

Therefore, there is a need to determine the optimal treatment method for inguinal hernias in the adolescent population. This study aimed to compare the postoperative outcomes of inguinal hernia repair using mesh with other established methods that do not use mesh in late adolescent patients.

Go to :

This study was a retrospective file review of patients who underwent inguinal hernia repair at a single institution (Armed Forces Capital Hospital, Seongnam, Korea) from January 2013 to December 2017 during their military service. Patients aged between 18 and 21 years old were included in the study. Patients who underwent emergency operation were excluded. Finally, 243 patients were enrolled the study. Patients were divided into 2 groups depending on whether or not the operation method involved mesh implantation; mesh and no-mesh group.

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Armed Forces Capital Hospital (No. AFCH-20-IRB-003). All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Requirement to obtain informed consent was waived by the IRB for this study based on the retrospective chart review design only, with no more than minimal risk.

The operative method for inguinal hernia was determined by the surgeon's preference and included Bassini, high ligation, Lichtenstein, and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) repair. There was no case of transabdominal preperitoneal repair, and the mesh was anchored using fibrin glue rather than tacker in TEP cases.

Preoperative patient characteristics, hernia and operation details (Bassini, high ligation, Lichtenstein, and TEP), and immediate postoperative outcomes including length of stay, pain, and complications were recorded for all patients. Complications were counted in accordance with Clavien-Dindo classification and chronic postoperative inguinal pain (CPIP); recurrences were not included in this complication rate. Data on recurrence and chronic pain were collected during the outpatient follow-up.

Postoperative pain was measured using the numeric rating score (NRS) during the first 5 postoperative days (POD) [13]. The maximum pain intensity at any time during 5 days was defined as NRSmax, and the average score over 5 days was defined as NRSavg [14]. CPIP was defined as prolonged inguinal pain for more than 6 months after surgery [1516].

We compared patients' baseline characteristics, immediate postoperative outcomes, and the occurrence of chronic pain between the 2 groups. Nominal data were compared using the chi-square test, and continuous parametric data were compared using the t-test. Recurrence rate was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test.

In the subgroup analysis of outcomes for the different operative methods, continuous parametric data were compared using analysis of variance, and the Bonferroni correction was used for the post hoc analysis. The criterion for statistical significance was P-value < 0.05.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows ver. 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Go to :

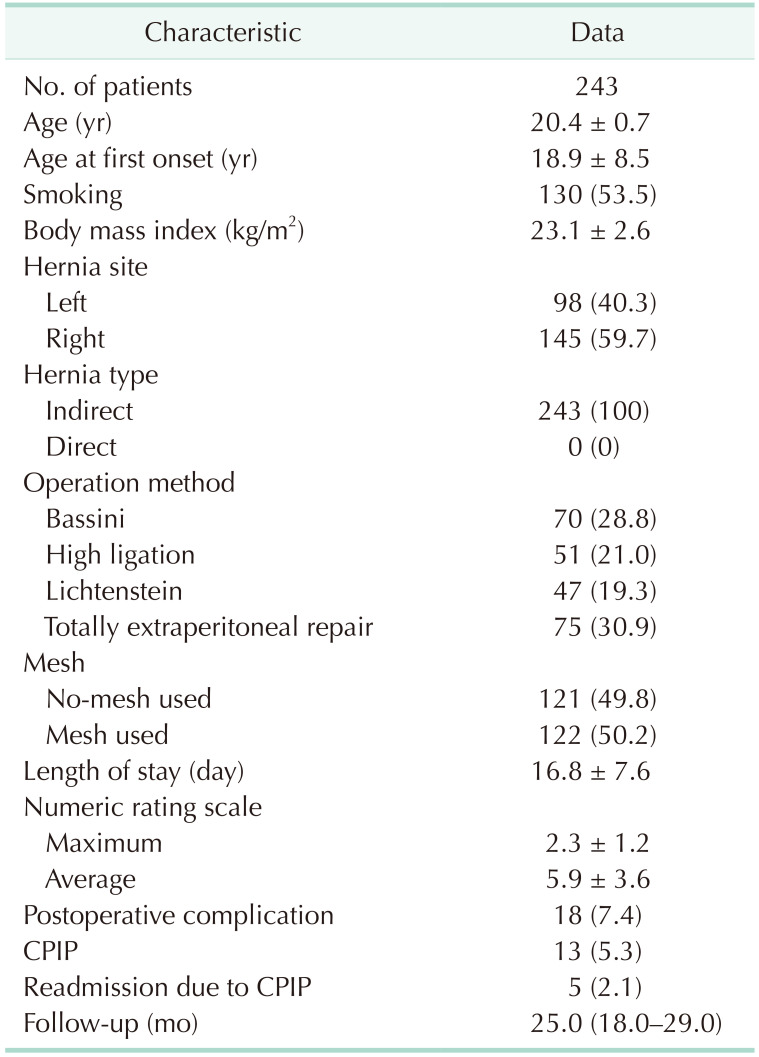

The clinical characteristics of the 243 patients are shown in Table 1. All of the enrolled patients were males, and their mean age was 20.4 ± 0.7 years. All of the enrolled patients had indirect inguinal hernia. The mean length of stay was 16.8 ± 7.6 days, and the median follow-up duration was 25.0 months (range, 18.0–29.0 months).

Half of the patients (n = 122, 50.2%) received a mesh during their hernia repair, whereas the other half (n = 121, 49.8%) were treated with different alternative repair methods.

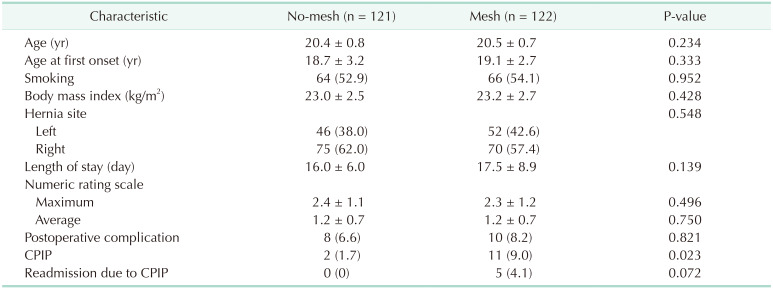

There were no significant differences in the baseline and clinical characteristics between the mesh and no-mesh groups except for the CPIP rate (mesh vs. no-mesh, 9.0% vs. 1.7%; P = 0.023). Major complications (corresponding to Clavien-Dindo Classification IIIa and higher) were not observed in either of the groups (Table 2).

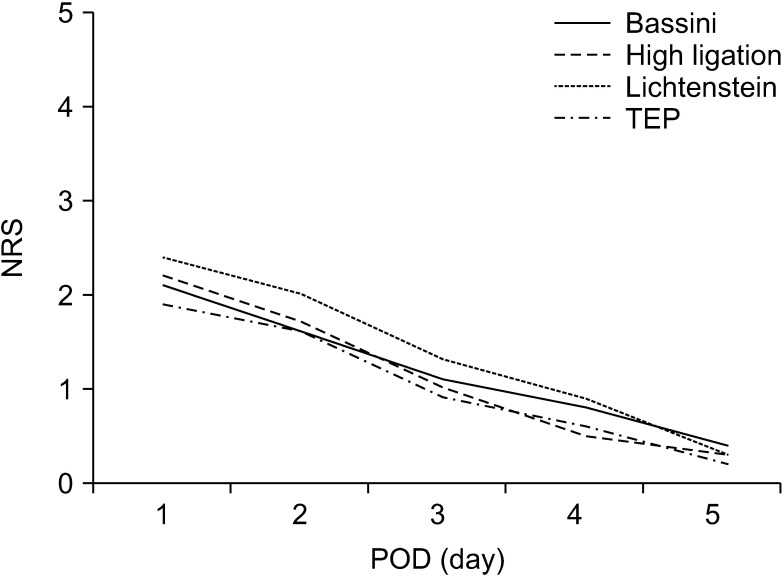

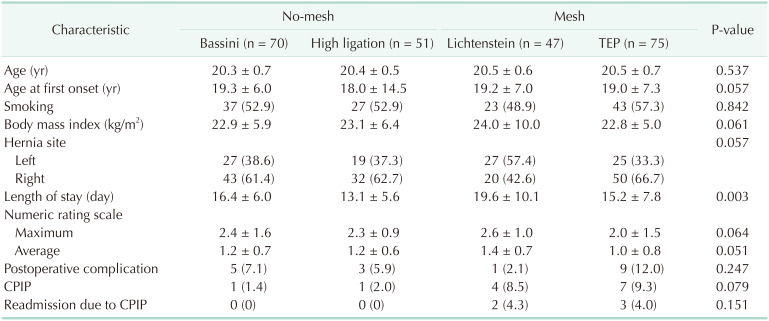

In the subgroup analysis for the different operation methods, immediate postoperative pain in accordance with POD did not differ significantly among the 4 methods (POD 1, P = 0.136; POD 2, P = 0.094; POD 3, P = 0.114; POD 4, P = 0.139; and POD 5, P = 0.335) (Fig. 1). However, the length of stay was significantly different between the 4 methods (P = 0.003). In the post hoc analysis, there were significant differences between the high ligation (removal of the hernia sac only) and Lichtenstein groups on the length of stay (high ligation vs. Lichtenstein, 13.1 ± 5.6 vs. 19.6 ± 10.1; P = 0.002) (Table 3).

There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (mesh vs. non-mesh) in the recurrence analysis (2-year recurrence rate mesh vs. non-mesh, 2.6% vs. 0.8%; P = 0.194). The hazard ratio for the mesh group compared with that for the no-mesh group was 0.26 (P = 0.228) (Fig. 2).

Go to :

Across the lifespan, the incidence of inguinal hernias is lowest (<0.25%) in late adolescence [2]. Because of this low incidence, study data on this group are relatively limited. In the Republic of Korea, military service for approximately 2 years is mandatory for most men over the age of 18 years [17]. As a result, most of the late adolescent male patients with inguinal hernias primarily visit the Armed Forces Hospital, which enabled us to accumulate the data reported in this study.

Based on the nature of the armed forces, most of the patients completed their convalescence at the hospital and were only discharged once they had fully recovered [18]. In other words, their hospital stay was longer than that of the general population due to other reasons [19]. While patients who underwent Lichtenstein repair stayed longer than patients who underwent high ligation in our study, 3 of the patients with Lichtenstein repair stayed longer after recovering from surgery because of orthopedic problems. Although the length of stay can be a useful parameter to estimate surgical outcomes in the general population, it might not correlate with surgical outcomes in our patients [20].

Since we were aware of this factor, we applied the pain scale that was routinely measured. Because postoperative pain frequently delays discharge, pain is used as an indirect parameter to evaluate surgical outcomes [21]. In the pain analysis, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups in our study. The groups also showed similar postoperative complication rates. Overall, there was no difference in the immediate postoperative parameters between patients undergoing repair with or without mesh.

The recurrence rate was also not significantly different between the 2 groups. However, we should interpret this result carefully because the study period was for only 2 years. Several studies have shown that the use of a mesh reduced the recurrence rate after inguinal hernia repair [2223]. A study that investigated the 5-year recurrence rate in young males also found a statistically significant difference between the mesh and no-mesh group [10]. Even though the recurrence rates in our study were similar, there is a possibility that a significant difference might be demonstrated during long-term follow-up.

Although the recurrence rate after hernia repair without mesh is higher than that with mesh in young males, some surgeons suggest that this rate is acceptable, and that hernia repair without mesh is an efficient method [24]. The reason is the relatively high rate of CPIP observed in young patients [25]. However, other factors than age may induce CPIP and have to be simultaneously considered when choosing the best surgical method. For example, it has been reported that mesh decreases CPIP in general population [5]. Yet, this was not observed in a study of young males only [9]. On the contrary, in our study, we found a higher CPIP rate in late adolescent male patients with mesh. Furthermore, a laparoscopic approach is reported to decrease CPIP rate compared with an open approach [26]. However, we did not observe a difference in CPIP between the 2 approaches when mesh was used. Our data showed that mesh increased CPIP rate regardless of the surgical method (open vs. laparoscopic) in late adolescent patients.

The clinical features and course of CPIP have shown some further interesting aspects in previous studies. About 45% of patients (n = 5) with CPIP in the mesh group experienced moderate to severe CPIP and needed admission. Moreover, in the majority of patients (n = 4), the pain characteristics were similar to nociceptive but not neuropathic pain, and all pain had decreased after one year [27]. CPIP seems to be worse in adolescents, severe enough to require admission. However, the pain also improves more dramatically compared with other age groups.

This finding might be related to ongoing physical development during adolescence. Biological growth is one of the major factors that determine adolescence [28]. Therefore, although CPIP caused by mesh is generally explained by chronic inflammation or nerve entrapment, biological growth might be a powerful factor in late adolescence when the mesh might cause tension that induces CPIP [29].

In summary, the immediate postoperative outcomes and recurrence rates after hernia repair in our late adolescent patients showed similar trends as those in the general population. However, the rate of CPIP was significantly higher after hernia repair with mesh than that in repairs without mesh, and we explain this with the unique nature of late adolescence. This period of life is relatively short compared with the lifespan of patients, which might justify a tailored approach, such as watchful waiting until adulthood [30]. However, to clarify this aspect, further studies are needed.

Our study has several limitations. First, this study was retrospective and had a small sample size. Well-designed and larger studies are required to verify our findings. Second, due to loss to follow-up of retired soldiers, this study was short-term, with a median follow-up of about 2 years. Although this allowed us to evaluate the immediate postoperative outcomes, the duration was insufficient to show a statistically significant difference in recurrence rates. Long-term follow-up, such as telephone survey follow-up, is necessary to clarify recurrence rates in this patient population. Finally, our patients were all relatively healthy because people with comorbidities are exempted from military service. Therefore, our results could be slightly different compared to late adolescents in the general population. Nonetheless, our study provides meaningful insights into the clinical outcomes of hernia repair in late male adolescence.

In conclusion, our retrospective study showed that the use of mesh in the repair of inguinal hernia in late adolescent male patients increased CPIP. Larger and randomized studies are required to investigate these results further.

Go to :

Notes

Fund/Grant Support: This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences (KIRAMS), funded by Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Republic of Korea (No. 50543-2020).

Go to :

References

2. Burcharth J, Pedersen M, Bisgaard T, Pedersen C, Rosenberg J. Nationwide prevalence of groin hernia repair. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e54367. PMID: 23342139.

4. Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Risk factors for inguinal hernia among adults in the US population. Am J Epidemiol. 2007; 165:1154–1161. PMID: 17374852.

5. HerniaSurge Group. Internat ional guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia. 2018; 22:1–165.

6. Othersen HB Jr. The pediatric inguinal hernia. Surg Clin North Am. 1993; 73:853–859. PMID: 8378824.

7. Rosenberg J. Pediatric inguinal hernia repair: a critical appraisal. Hernia. 2008; 12:113–115. PMID: 18060351.

8. Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia. 2009; 13:343–403. PMID: 19636493.

9. Bay-Nielsen M, Nilsson E, Nordin P, Kehlet H. Swedish Hernia Data Base the Danish Hernia Data Base. Chronic pain after open mesh and sutured repair of indirect inguinal hernia in young males. Br J Surg. 2004; 91:1372–1376. PMID: 15376186.

10. Bisgaard T, Bay-Nielsen M, Kehlet H. Groin hernia repair in young males: mesh or sutured repair? Hernia. 2010; 14:467–469. PMID: 20454990.

11. Criss CN, Gish N, Gish J, Carr B, McLeod JS, Church JT, et al. Outcomes of adolescent and young adults receiving high ligation and mesh repairs: a 16-year experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018; 28:223–228. PMID: 29261090.

12. Bruns NE, Glenn IC, McNinch NL, Rosen MJ, Ponsky TA. Treatment of routine adolescent inguinal hernia vastly differs between pediatric surgeons and general surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2017; 31:912–916. PMID: 27357926.

13. Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978; 37:378–381. PMID: 686873.

14. Meissner W, Mescha S, Rothaug J, Zwacka S, Goettermann A, Ulrich K, et al. Quality improvement in postoperative pain management: results from the QUIPS project. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008; 105:865–870. PMID: 19561807.

15. Aasvang E, Kehlet H. Chroni c postoperative pain: the case of inguinal herniorrhaphy. Br J Anaesth. 2005; 95:69–76. PMID: 15531621.

16. Charalambous MP, Charalambous CP. Incidence of chronic groin pain following open mesh inguinal hernia repair, and effect of elective division of the ilioinguinal nerve: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hernia. 2018; 22:401–409. PMID: 29550948.

17. Jung JS, Sohn M. Korea's military service policy issues and directions for mid- & long-term development. Korean J Def Anal. 2011; 23:473–488.

18. Rusk HA, Taylor EJ. Army air forces convalescent training program. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. 1945; 239:53–59.

19. Wittenbecher F, Scheller-Kreinsen D, Röttger J, Busse R. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay associated with open-mesh, totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair, and transabdominal preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: an analysis of observational data using propensity score matching. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27:1326–1333. PMID: 23093240.

20. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017; 152:292–298. PMID: 28097305.

21. Rawal N. Current issues in postoperative pain management. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016; 33:160–171. PMID: 26509324.

22. EU Hernia Trialists Collaboration. Mesh compared with non-mesh methods of open groin hernia repair: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Surg. 2000; 87:854–859. PMID: 10931018.

23. Kehlet H, Bay-Nielsen M. Danish Hernia Database Collaboration. Nationwide quality improvement of groin hernia repair from the Danish Hernia Database of 87,840 patients from 1998 to 2005. Hernia. 2008; 12:1–7. PMID: 17939015.

24. van Kerckhoven G, Toonen L, Draaisma WA, de Vries LS, Verheijen PM. Herniotomy in young adults as an alternative to mesh repair: a retrospective cohort study. Hernia. 2016; 20:675–679. PMID: 27522362.

25. Bjurstrom MF, Nicol AL, Amid PK, Chen DC. Pain control following inguinal herniorrhaphy: current perspectives. J Pain Res. 2014; 7:277–290. PMID: 24920934.

26. Bignell M, Partridge G, Mahon D, Rhodes M. Prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic (transabdominal preperitoneal-TAPP) versus open (mesh) repair for bilateral and recurrent inguinal hernia: incidence of chronic groin pain and impact on quality of life: results of 10 year follow-up. Hernia. 2012; 16:635–640. PMID: 22767210.

27. Hu QL, Chen DC. Approach to the patient with chronic groin pain. Surg Clin North Am. 2018; 98:651–665. PMID: 29754628.

28. Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018; 2:223–228. PMID: 30169257.

29. Massaron S, Bona S, Fumagalli U, Battafarano F, Elmore U, Rosati R. Analysis of post-surgical pain after inguinal hernia repair: a prospective study of 1,440 operations. Hernia. 2007; 11:517–525. PMID: 17646895.

30. Sarosi GA, Wei Y, Gibbs JO, Reda DJ, McCarthy M, Fitzgibbons RJ, et al. A clinician’s guide to patient selection for watchful waiting management of inguinal hernia. Ann Surg. 2011; 253:605–610. PMID: 21239979.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download