INTRODUCTION

An abnormal liver function test (LFT) is commonly observed in pediatric patients with acute infectious diseases such as respiratory tract infections, gastroenteritis, and urinary tract infections.

12 Most patients only show modest aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation; however, some patients might have more severe hepatic injuries showing other LFT abnormalities such as elevated bilirubin levels, prolonged prothrombin time, and hypoalbuminemia.

1 Some pathogens, such as tuberculosis,

Campylobacter,

Clostridium perfringens, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and herpes virus could cause not only transient abnormal LFTs but also acute liver failure and hepatic encephalopathy.

1 This condition is usually self-limiting; however, sometimes it can persist for longer than a year, which could annoy parents and physicians.

2 The exact pathophysiology of liver involvement in systemic infection is not well known; it can induce hepatic injury through direct invasion, indirect toxin-induced injury, or cytokines.

1

Nonspecific reactive hepatitis (NRH) is defined as a nonspecific inflammatory process without any specific histologic finding suggestive of a specific liver disease.

34 NRH is usually used to refer to secondary liver injury due to extrahepatic disease without any primary cause of liver-specific disease. However, it is unclear which pathogen could be regarded as the cause of NRH, from among those such as enterovirus, CMV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), rotavirus, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), because they primarily evoke systemic infection and are known to be associated with liver injury.

4 Although it should be confirmed through histology, due to the relatively mild clinical course of the disease and invasiveness of liver biopsy, we usually regard NRH as having no symptoms indicating hepatitis and showing elevation of liver enzymes in their blood test without any evidence of hepatotropic virus or other specific liver disease.

4 Therefore, in clinical situations, it might be acceptable to consider NRH if there is no evidence of other specific causes and symptoms of hepatitis and the AST and ALT are elevated in acute infectious diseases.

To our knowledge, there are only a few studies and no clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of NRH. We conducted a multicenter study to elucidate the cause of NRH and factors associated with prolongation of liver enzyme elevation, which are of concern to physicians. Furthermore, through this multicenter study, we might know the physician's approach to NRH in real-world practice in Korea.

Go to :

METHODS

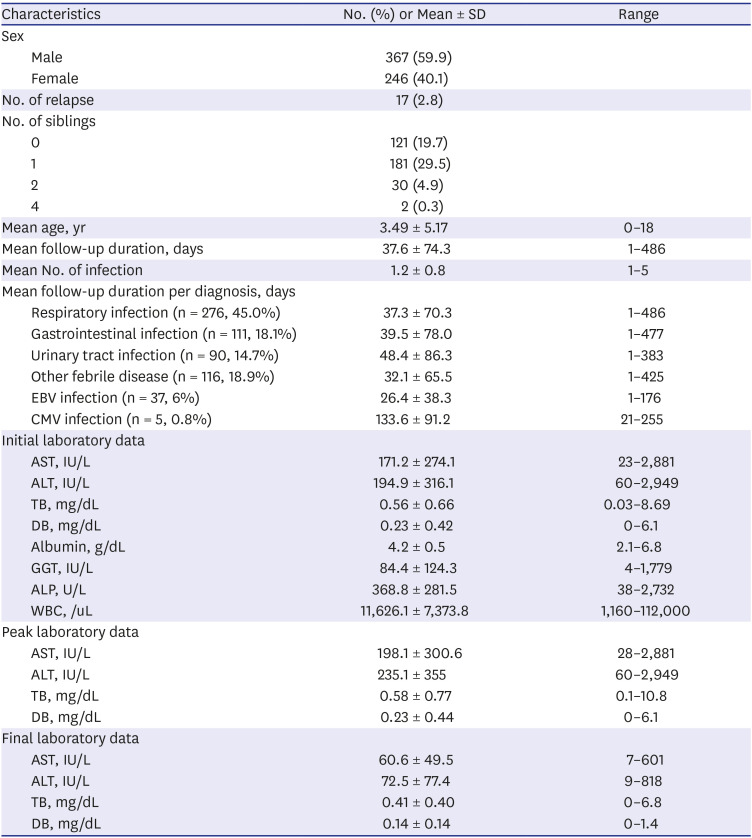

A retrospective study was conducted on all patients younger than 18 years who visited any of the six tertiary teaching hospitals around Korea in December 2016 to December 2018 for acute infectious diseases and showed ALT levels above 60 IU/L which are twice the upper limit of the normal range.

5 Other previous studies among Korean children and adolescent, ALT 30 IU/L or ALT 30–33 IU/L for male adolescents and 19–25 IU/L for female adolescents could be used for reference range based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data.

67

Patients with confirmed other disease that cause LFT elevation such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, hepatotropic virus infections, autoimmune disease, muscular disease, and other toxic hepatitis were excluded within the scope of hepatitis work up.

The number of infections during the period of elevated liver enzyme levels was measured; in cases with ALT recovery followed by recurrent ALT elevation above 60 IU were defined as ‘relapse of the LFT elevation.' We collected the results of initial LFTs such as AST, ALT, total bilirubin (TB), direct bilirubin (DB), alkaline phosphatase, gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT), albumin, white blood cell counts, and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR). We also collected the peak and final AST, ALT, TB, and DB levels.

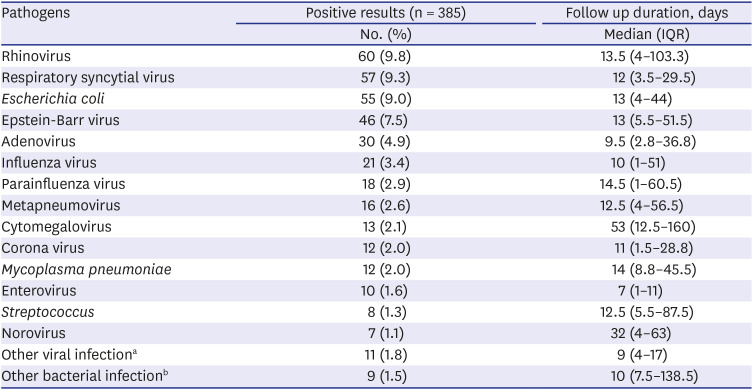

We categorized the infections that cause LFT elevation into six groups: respiratory infection, gastrointestinal (GI) infection, urinary tract infection (UTI), other febrile disease, and EBV and CMV infection. We evaluated the etiology of the infection using culture, polymerase chain reaction, and rapid antigen testing.

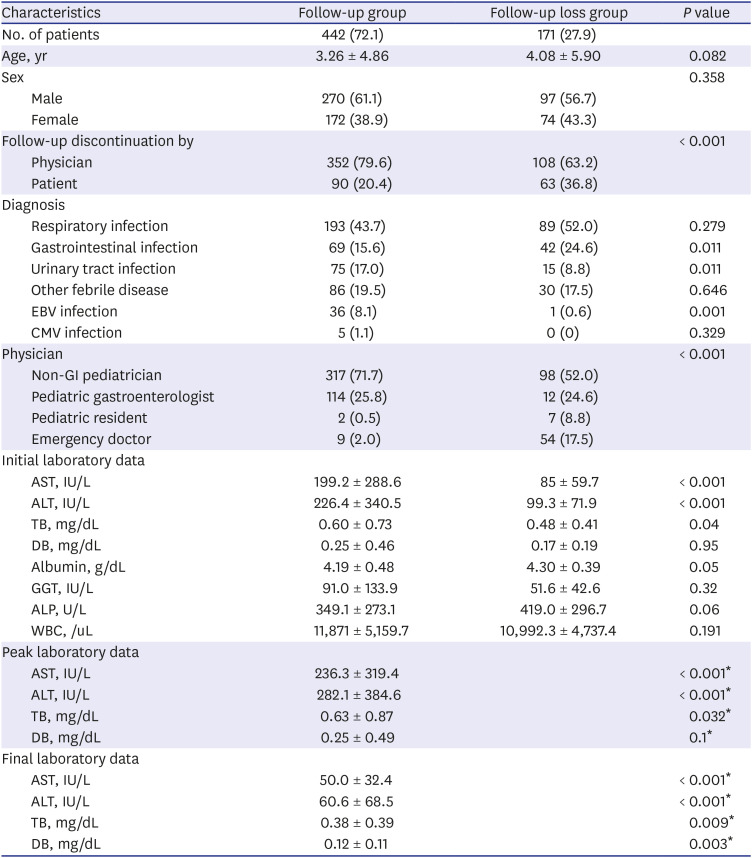

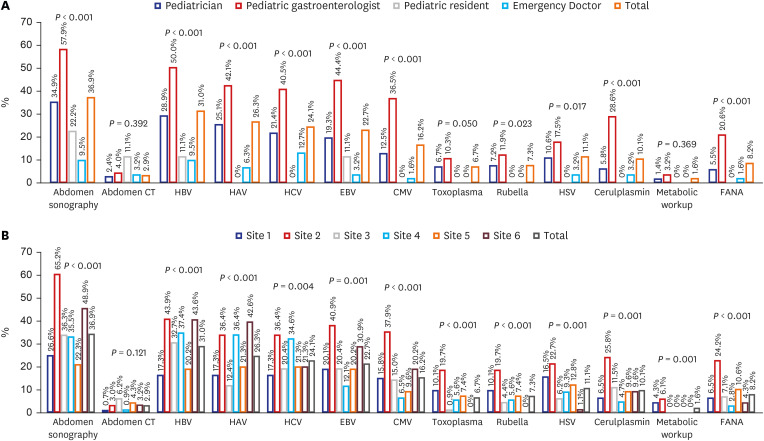

To evaluate the actual practice for managing NRH, we collected data on the medical specialty of the attending physician who followed up the subject, as well as those on follow-up duration, percentage of follow-up loss, and the investigation of NRH. We defined the follow-up group as the patients undergoing repetition of the LFT, and the follow-up loss group as the patients who underwent only one LFT, although the ALT level was above 60 IU/L. We grouped physicians into four groups: non-GI pediatricians, pediatric gastroenterologists, pediatric residents, and emergency doctors. We evaluated hepatitis workup, such as radiologic examination, viral markers, and metabolic screening, according to physician groups and institutions. We evaluated the frequencies of tests such as those involving hepatitis B surface antigen, antibody, and other antibodies or polymerase chain reaction for hepatitis A virus, hepatitis C virus, EBV, CMV, toxoplasma, and HSV for infectious workup. We also checked the number of metabolic tests, such as the neonatal screening test, serum and/or urine amino-acid, organic acid, and ceruloplasmin for metabolic disease and fluorescent antinuclear antibody (FANA) for autoimmune disease.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 20.0 statistical program software (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics for continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) according to their distribution. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Analysis of the differences between categorical variables was performed using the χ2 test. Based on the distribution of the variables, the t-test and Mann-Whitney test were conducted to compare the means between the groups. To investigate the factors associated with ALT recovery time (time to ALT < 60 IU), the Cox proportional-hazards model was used. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

All institutional review boards (IRBs) of the six hospitals approved the study and provided waiver of informed consent; Korea University Anam Hospital IRB No. 2020AN0123, Chung-Ang University Hospital IRB No. 1812-020-16236, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital IRB No. 2019-07-021-004, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital IRB No. 2019-09-012, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital IRB No. 2019-07-021 and Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital IRB No. 2019-04-022. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Systemic infection-related liver enzyme elevation in children is a common clinical situation.

24 Although hepatic enzymes are increased in various diseases such as sepsis, respiratory infections, digestive diseases, and urinary tract infections, the clear mechanism of liver injury after systemic infection is still unknown.

1 In addition, there is no clinical guidelines, and there are only a few studies about these conditions, follow-up interval, period, and diagnostic modalities that vary widely among doctors and institutions. The purpose of this study was to investigate the clinical characteristics of LFT elevation after systemic infection and the management by doctors and hospitals in the real world in Korea.

In the present study, ALT levels in some patients were elevated above 2,000 IU, which was 50 times higher than the normal reference range, but none of them progressed to hepatic failure or had other signs of severe hepatic damage such as severe hyperbilirubinemia, clinically significant coagulopathy, or hepatic biosynthesis/clearance defects. Considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria of this study, these findings are natural. However, it is noteworthy that ALT can be elevated to the extent that severe hepatic pathologies are suspected, even in non-specific benign conditions.

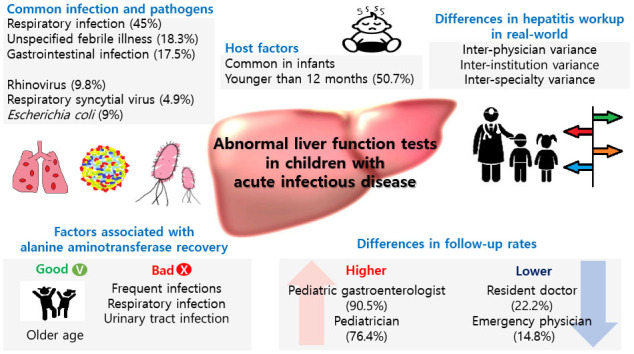

Respiratory infection was the most common cause of the NRH, and rhinovirus was the most common pathogen following RSV and adenovirus in our study. Interestingly, according to the Korean Disease control and Prevention Agency (kdca.go.kr), most common pathogen causing acute respiratory infection during our study period, was rhinovirus, followed by RSV, adenovirus and parainfluenzavirus.

8 Previous Korean studies conducted in 2005–2014 and 1996–2006 also reported that respiratory infection was the most common infection focused in NRH; however, adenovirus and RSV were more common than rhinovirus.

24 Some case reports also show that these respiratory viruses can cause liver injury during systemic infection.

91011121314 In addition to viruses, bacterial pneumonia (e.g.,

Streptococcus pneumonia,

Haemophilus influenza,

Staphylococcus aureus, or

Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and mycoplasma pneumonia can cause hepatocellular damage and cause laboratory abnormalities, including hyperbilirubinemia.

1

Similar to several previous reports, we found that GI (18.1%) and UTI (14.7%) were also common causes of NRH.

24 One small pediatric study showed the relationship between reactive hepatitis and gastrointestinal infection, and rotavirus infection was associated with significantly higher transaminase levels than the infection with the norovirus or adenovirus group.

15 However, in our study, adenovirus was more common than other GI pathogens. In terms of UTI, a previous Korean study reported that 20.5% of patients had elevated liver enzyme levels during urinary tract infection and the liver enzyme levels became normal within 1 month, except in one of 249 cases.

16 However, in the current study, the mean follow-up duration of 90 patients with UTI was 48.4 ± 86.3 days, and

E. coli infection showed a somewhat longer duration (median, 13 days; IQR, 4–44 days) of ALT elevation than the previous study. This difference was probably due to the different study designs and study populations.

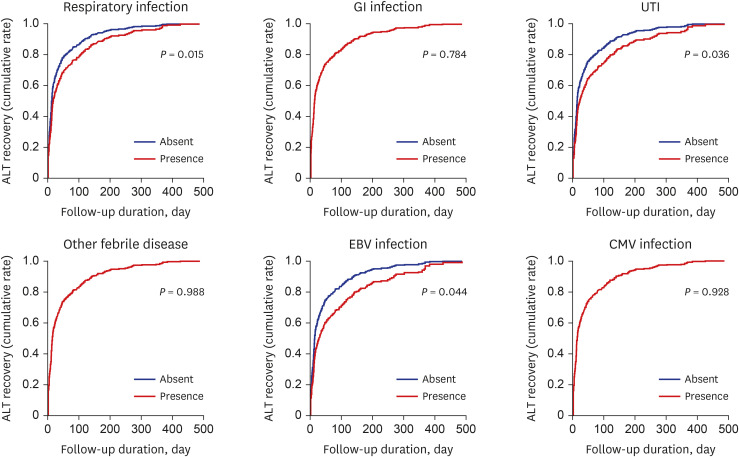

We found that the older age of patients was related to a shorter duration of hepatic enzyme elevation; the mean age of our study patients was 3.5 years, and 311 (50.7%) were younger than 12 months. Other studies have also shown that children younger than 5 years commonly experience increased liver enzyme levels during systemic infections.

410131516 As the exact mechanism of NRH remains unknown, the explanation of the poorer prognosis in younger infants is even more difficult. In terms of the mechanism of NRH, Polakos et al.

12 suggested that the formation of inflammatory foci, including apoptotic hepatocytes, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, and Kupffer cells might be related to the ‘collateral damage’ of the liver in many extrahepatic viral infections.

12 In bacterial infection with/without septic conditions, the interaction between Kupffer cells, hepatocytes, neutrophils, and endothelial cells in response to systemic infection is thought to result in hepatic dysfunction.

1718 Assuming the above-mentioned mechanism, poorer prognosis in young infants may be related to different hepatic immune functions and/or different hepatic functional reservoirs in younger children; however, we have failed to find supporting evidence.

Although the mean ALT (99.3 ± 71.9 IU/L) in the follow- up loss group was significantly lower than the follow-up group (282.1 ± 384.6 IU/L), it was still high three times higher more than normal range.

567 A considerable number of patients (n = 108, 17.6%) discontinued follow-up by physicians' decisions in this study. Most of them were seen by pediatricians and emergency doctors. It is impossible to make a final diagnosis of the LFT elevation in the follow-up loss group due to a potential cause of the LFT elevation. Since most of the emergency departments are busy, LFT elevation among children with acute infectious disease is easily overlooked. Physicians should keep in mind that there will always be a possibility of other cause of LFT elevation except for NRH.

Furthermore, the hepatitis workup was also significantly different between physicians and hospitals. Pediatrician and pediatric gastroenterologists usually repeat the LFT and perform hepatitis workup, such as sonography and tests involving other viral markers, more frequently than other doctors. This difference might be related to differences in clinical concerns due to their specialized medical fields and/or experiences and knowledge of liver diseases. Due to the fact that NRH is the diagnosis of exclusion, the diagnosis could be changed by physician's extent of hepatitis workup and follow up duration. Although the generalist-specialist differences are not rare in many diseases,

192021 the general physicians have to follow up with these patients to see the LFT normalization and appropriatly refer to the gastroenterologist if necessary.

Inborn errors of metabolism are also associated with liver dysfunction and jaundice in young children. In many cases, abnormal liver function test results are the earliest sign of such diseases; therefore, proper evaluation and treatment are required to avoid undesirable outcomes.

22 However, in our study, only a few patients (1.6%) underwent metabolic studies, even by pediatric gastroenterologists. Similar to the absence of cases with liver failure mentioned previously, this result might be related to the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the current study. Therefore, this could not reflect the actual number of metabolic screenings for pediatric LFT elevation. The clinical importance of metabolic screening cannot be overlooked. More attention toward metabolic diseases might be required to some extent.

When we encounter children with abnormal LFTs, we should consider various reasons for hepatitis in children, including infectious, toxic, metabolic, autoimmune, and others.

2324 There are some review articles suggesting that we should repeat LFTs, including AST, ALT, GGT, and creatinine phosphokinase, if there is a persistent increase in liver enzyme levels; it suggested a stepwise approach to evaluate the etiology.

24 It also suggested that the first-line panel should consist of liver ultrasonography and other frequent causes such as a hepatotropic virus and ceruloplasmin (> 3 years). Second-and third-line investigations should be considered to exclude autoimmune hepatitis and other metabolic diseases, including liver biopsies.

24 However, it remains unclear when children have only mild transaminase elevation with a recent infection, because we should consider the cost-benefit effect, risk of recurrent vein puncture, and delayed diagnosis. We need to thoroughly review the patient's history, physical examination, and laboratory results to evaluate the timely and correct diagnosis of reactive hepatitis in children.

The limitations of this study are as follows. This was a retrospective study, and we collected data from six tertiary teaching hospitals, which might not reflect nationwide Korean data. However, through a multi-center study, we could determine the clinical characteristics, associated etiology, prognosis, and hepatitis workup for LFT abnormalities after a systemic infection. Second, because we excluded patients with other liver diseases within the scope of the hepatitis workup among all patients with LFT elevation, diagnoses other than NRH might be included especially in the patients who were not able to follow up. However, from this population, we could report real-world data on the differences among physicians and institutions in hepatitis workup under these conditions. This could be explained by the lack of evidence in this field, although it is a common clinical situation, especially in the pediatric field. Further studies on the etiology, mechanism, and prognosis of NRH are needed to establish consistent guidelines.

In conclusion, Abnormal liver function test results after systemic infection was common in respiratory infection and under the age of 1 year. Age, number of infections, and initial results of LFTs were significantly associated with ALT recovery time. Inter-physician, inter-institution, and inter-specialty variances were observed in real-world practice. Therefore, the development of standardized clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of NRH should be considered for appropriate and consistent management.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download