INTRODUCTION

The exchange of students studying abroad is being offered in various study fields on a worldwide basis. The total number of foreign college students studying abroad in Korea increased from 123,858 students in 2017 to 142,205 students in 2018, and 160,165 students in 2019, and of these 71,067 (44.4%) were Chinese college students [

1]. They chose to study abroad in Korea because they were interested in Korean culture as results of the Korean wave, excellence in their major, a low cost of living, and personal safety [

2].

Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea are familiar with Korean food due to Korean wave media such as K-Pop and K-Drama [

3]. However, it is difficult for them to adapt due to differences in food culture and changes in lifestyle. Most Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea live self-boarding or in college dormitories, but are more likely to eat out or late-night snack than eating in a college cafeteria selling mainly Korean food [

4]. However, when Chinese students eat out, they were stressed by the lack of diversity in Korean restaurants menus and difficulty choosing menu items [

5]. The frequency of meal was changed irregularly and frequency of skipping breakfast increased by 20% after the migration of Chinese college students studying abroad compared to before moving to Korea [

6]. Changes in dietary habits of foreign students studying abroad after migration were reported to affect health adversely such as poor diet, increased consumption of cooked meals, overweight, and obesity [

789]. Due to these differences in food culture and the need for convenience almost a quarter of the Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea use a convenience store more than 5 times a week and tend to rely on home meal replacement [

10].

Home meal replacement (HMR) refers to products that are manufactured, processed, and packaged in a complete and semi-cooked form and can be consumed immediately or after simple cooking procedures [

11]. HMR is classified as Ready to Eat (RTE), Ready to Heat (RTH), Ready to Cook (RTC), or Ready to Prepare (RTP). The market size of HMR in Korea was about 3,200 billion won in 2018 and is expected to reach about 5,000 billion won in 2022 [

12]. On the other hand, the market size of HMR in China was about 500 billion yuan in 2018 (KRW 85.9 trillion) and was expected to increase by 16.0% annually [

13]. In Korea in 2017, RTE foods, which require no additional preparation, such as lunchboxes,

gimbap, and sandwiches accounted for 52.1% of the HMR market size and RTH foods such as processed rice and soup that can be simply heated accounted for 42.0% [

12], Korean singles in metropolitan were satisfied with the positive psychology and convenience of HMR [

14]. In the Chinese HMR market in 2018, canned food accounted for 38.0%, semi-finished food materials for 31.0%, and instant noodles for 16.0%, which means that the market size of RTC products is substantial [

13]. However, energy, carbohydrate, and protein per serving size of RTH products (fried rice, cup rice, and porridge) sold in Korea, were all lower than the Korean dietary reference intake. And the average energy of the products was about 324 kcal (12.4% of 2,600 kcal for males aged 19–29), so it was reported that there was insufficient nutrition as one meal [

15]. In addition, the average sodium in convenience store lunchboxes was contained about 1,237 mg, which was reported as 62% of the recommended daily intake of sodium in World Health Organization [

16].

Recently, countermeasures against the spread of coronavirus disease 2019, such as movement restrictions and social distancing have resulted in increases in the consumption of HMR in Korea and China [

1718]. Furthermore, for the reasons mentioned above, Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea would prefer HMR, but the consumption of unhealthy HMR products can lead to nutritional imbalance. Thus, a range of customized HMR is needed to satisfy the dietary needs of not only Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea, but also Korean and Chinese college students.

Cultural differences between Koreans and Chinese showed differences in the emotions about HMR products [

19], and consumers' emotions about foods were reported to have an effect on food preference and consumption behaviors [

2021]. In this regard, Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea may have changed their emotions and preferences for HMR products as they adjust to life in Korea. Therefore, this study was conducted with the aim of suggesting developmental directions of HMR products by comparing consumption behaviors and development needs of HMR among Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea, Chinese college students in China, and Korean college students in Korea.

Go to :

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

The subjects of this cross-sectional study were 188 Chinese college students who have studied in a metropolitan area of Korea for more than 1 year (188 CSK), 200 Chinese college students in Shenyang, China who have never been to Korea (200 CSC), and 200 Korean college students in a metropolitan area of Korea (200 KSK). All subjects had an experience of HMR consumption and voluntarily agreed to participate in this study. A survey was conducted by face-to-face interviews using an anonymous self-administered questionnaire from January to April 2019. Out of the 588 questionnaires distributed, 18 questionnaires with incomplete data were excluded from the statistical analysis. Accordingly, the subjects of this study were composed of 570 students (180 CSK, 200 CSC, and 190 KSK). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inha University in Korea (No. 181113-4A).

Study procedure and contents

The questionnaire of this study was constructed based on those used in previous studies [

22232425] and was initially written in Korean and then translated into Chinese. After conducting a preliminary survey on 45 people (15 CSK, CSC, and KSK), a description of HMR was added to the questionnaire, and duplicate questions were deleted. The final questionnaire consisted of four sections that addressed consumption behaviors for HMR, the importance of attributes when selecting HMR, development needs for food groups and cooking methods for HMR, and preferences for foods (meats, fish, seafood, and vegetables).

General characteristics of the subjects included sex, age, residence type, and pocket money. These variables were used to test intergroup homogeneity.

Consumption behaviors for HMR were assessed using 6 items; utilization of HMR, reason for purchase, frequency of consumption, average purchase price per HMR, place of purchase, and person to eat together.

As regards importance when selecting HMR, 10 attributes were considered, that is, taste, freshness, amount, price, diversity, nutrition, hygiene, origin, appearance, and cooking method. These attributes were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, which ranged from 1 (very unimportant) to 5 (very important). We assumed that the higher the Likert score, the greater was the importance of the attribute when selecting HMR.

Development needs of HMR were assessed using 7 food groups, that is, rice, porridge, soup and stew, meat side dishes, fish or seafood side dishes, vegetable side dishes, and dessert and were assessed using 4 cooking methods, that is, grilling, frying, stir-frying, and boiling or steaming. Responses were scored using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unnecessary) to 5 (very necessary). We assumed that the higher the score, the greater was the developmental need.

Food preferences were assessed using 4 groups (meats, fish, seafood, and vegetables) that might be used as side dishes. The items included in these food groups were foods found to have high preferences in previous studies [

2226]. The survey was enabled multiple responses so that preferred food materials could all be selected.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means and standard errors. The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The χ

2 test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), or analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to determine the significances of intergroup differences among the CSK, CSC, and KSK. General characteristics (except for age), consumption behaviors for HMR, and food preferences of intergroup were compared using the χ

2 test, and ages were compared using ANOVA. Previous studies [

272829] reported that consumption behaviors of convenience foods among Korean college students differ depending on sex, age, residence type, and pocket money. So, non-homogeneous general characteristics were adjusted to covariates, and the three groups were compared by controlling the effect of them. Intergroup differences regarding the importance of attributes when selecting HMR, the development needs of food groups, and cooking methods were compared using ANCOVA adjusted for sex, age, residence type, and pocket money. ANCOVA was used for multiple comparisons among groups and post-hoc test was performed using Bonferroni's method. Correlations among development needs regarding meat, fish or seafood, and vegetable side dishes and development needs regarding cooking methods for HMR, and importance when selecting HMR in each group were determined using Pearson's correlation coefficients. The level of significance was set at

P < 0.05.

Go to :

RESULTS

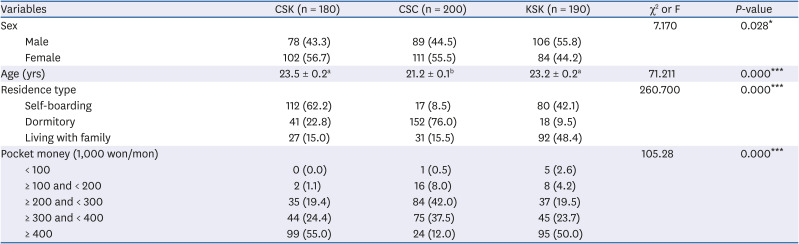

General characteristics of the study subjects

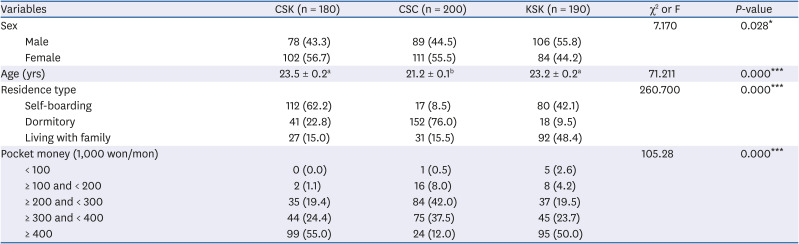

As shown in

Table 1, sex, age, residence type, and pocket money are shown a significant difference in the three groups. The proportion of male students was higher in the KSK, while proportions of females were higher in the CSK sand CSC than in the KSK (

P < 0.05). The average age in the CSC was significantly less than that in the CSK and KSK (

P < 0.01). Residence types showed a significant difference depending on country and study abroad (

P < 0.01). In pocket money, proportions with over 400,000 won to spend per month were higher in the CSK and KSK than in the CSC, whereas the proportion with from 200,000 won to less than 300,000 won to spend was higher in the CSC (

P < 0.01). All general characteristics differed significantly in the 3 groups, and thus, they were used as covariates.

Table 1

General characteristics of the subjects

|

Variables |

CSK (n = 180) |

CSC (n = 200) |

KSK (n = 190) |

χ2 or F |

P-value |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

7.170 |

0.028*

|

|

Male |

78 (43.3) |

89 (44.5) |

106 (55.8) |

|

Female |

102 (56.7) |

111 (55.5) |

84 (44.2) |

|

Age (yrs) |

23.5 ± 0.2a

|

21.2 ± 0.1b

|

23.2 ± 0.2a

|

71.211 |

0.000***

|

|

Residence type |

|

|

|

260.700 |

0.000***

|

|

Self-boarding |

112 (62.2) |

17 (8.5) |

80 (42.1) |

|

Dormitory |

41 (22.8) |

152 (76.0) |

18 (9.5) |

|

Living with family |

27 (15.0) |

31 (15.5) |

92 (48.4) |

|

Pocket money (1,000 won/mon) |

|

|

|

105.28 |

0.000***

|

|

< 100 |

0 (0.0) |

1 (0.5) |

5 (2.6) |

|

≥ 100 and < 200 |

2 (1.1) |

16 (8.0) |

8 (4.2) |

|

≥ 200 and < 300 |

35 (19.4) |

84 (42.0) |

37 (19.5) |

|

≥ 300 and < 400 |

44 (24.4) |

75 (37.5) |

45 (23.7) |

|

≥ 400 |

99 (55.0) |

24 (12.0) |

95 (50.0) |

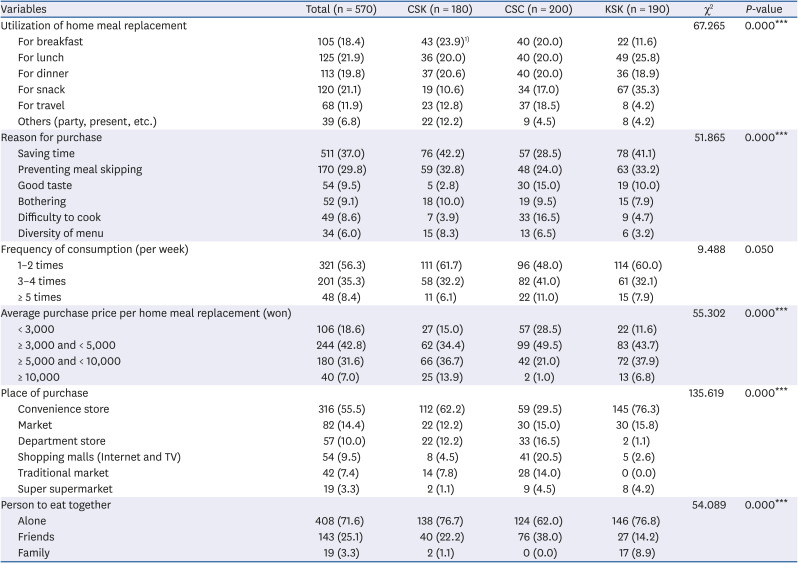

Consumption behaviors for home meal replacement

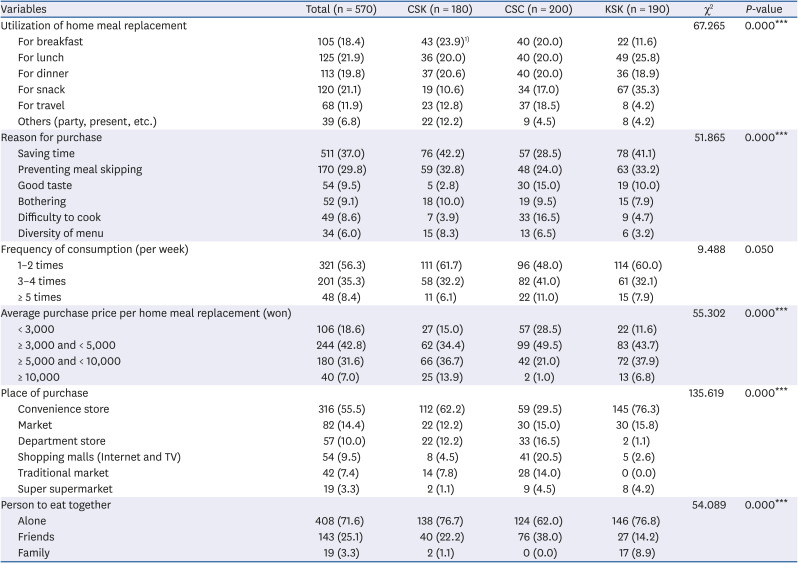

Consumption behaviors for HMR of the subjects are shown in

Table 2. The majority of students in the CSK and CSC consumed HMR as a substitute for home-cooked meals such as breakfast, lunch, and dinner, whereas those in the KSK mainly consumed HMR as a snack or lunch, and this intergroup difference was shown very significant (

P < 0.001). The reasons for purchasing HMR were also significantly different in the three groups (

P < 0.001). Subjects of all three groups showed high ‘saving time’ and ‘preventing meal skipping’, and intergroup differences were found for ‘good taste’ and ‘difficulty to cook’. In average purchase price per HMR, the proportion answering from 5,000 won to less than 10,000 won was highest for the CSK, while the proportion answering from 3,000 won to less than 5,000 won was higher in the CSC and KSK (

P < 0.001). As regards place of purchase, most in the CSK or KSK used a convenience store, in the CSC, shopping malls (internet and TV) and traditional market were used significantly higher than in the CSK and KSK (

P < 0.001). Three groups showed high responses to eating HMR alone, but intergroup differences were found for responses to eating HMR with friends and family (

P < 0.001).

Table 2

Consumption behaviors for home meal replacement

|

Variables |

Total (n = 570) |

CSK (n = 180) |

CSC (n = 200) |

KSK (n = 190) |

χ2

|

P-value |

|

Utilization of home meal replacement |

|

|

|

|

67.265 |

0.000***

|

|

For breakfast |

105 (18.4) |

43 (23.9)1)

|

40 (20.0) |

22 (11.6) |

|

For lunch |

125 (21.9) |

36 (20.0) |

40 (20.0) |

49 (25.8) |

|

For dinner |

113 (19.8) |

37 (20.6) |

40 (20.0) |

36 (18.9) |

|

For snack |

120 (21.1) |

19 (10.6) |

34 (17.0) |

67 (35.3) |

|

For travel |

68 (11.9) |

23 (12.8) |

37 (18.5) |

8 (4.2) |

|

Others (party, present, etc.) |

39 (6.8) |

22 (12.2) |

9 (4.5) |

8 (4.2) |

|

Reason for purchase |

|

|

|

|

51.865 |

0.000***

|

|

Saving time |

511 (37.0) |

76 (42.2) |

57 (28.5) |

78 (41.1) |

|

Preventing meal skipping |

170 (29.8) |

59 (32.8) |

48 (24.0) |

63 (33.2) |

|

Good taste |

54 (9.5) |

5 (2.8) |

30 (15.0) |

19 (10.0) |

|

Bothering |

52 (9.1) |

18 (10.0) |

19 (9.5) |

15 (7.9) |

|

Difficulty to cook |

49 (8.6) |

7 (3.9) |

33 (16.5) |

9 (4.7) |

|

Diversity of menu |

34 (6.0) |

15 (8.3) |

13 (6.5) |

6 (3.2) |

|

Frequency of consumption (per week) |

|

|

|

|

9.488 |

0.050 |

|

1–2 times |

321 (56.3) |

111 (61.7) |

96 (48.0) |

114 (60.0) |

|

3–4 times |

201 (35.3) |

58 (32.2) |

82 (41.0) |

61 (32.1) |

|

≥ 5 times |

48 (8.4) |

11 (6.1) |

22 (11.0) |

15 (7.9) |

|

Average purchase price per home meal replacement (won) |

|

|

|

|

55.302 |

0.000***

|

|

< 3,000 |

106 (18.6) |

27 (15.0) |

57 (28.5) |

22 (11.6) |

|

≥ 3,000 and < 5,000 |

244 (42.8) |

62 (34.4) |

99 (49.5) |

83 (43.7) |

|

≥ 5,000 and < 10,000 |

180 (31.6) |

66 (36.7) |

42 (21.0) |

72 (37.9) |

|

≥ 10,000 |

40 (7.0) |

25 (13.9) |

2 (1.0) |

13 (6.8) |

|

Place of purchase |

|

|

|

|

135.619 |

0.000***

|

|

Convenience store |

316 (55.5) |

112 (62.2) |

59 (29.5) |

145 (76.3) |

|

Market |

82 (14.4) |

22 (12.2) |

30 (15.0) |

30 (15.8) |

|

Department store |

57 (10.0) |

22 (12.2) |

33 (16.5) |

2 (1.1) |

|

Shopping malls (Internet and TV) |

54 (9.5) |

8 (4.5) |

41 (20.5) |

5 (2.6) |

|

Traditional market |

42 (7.4) |

14 (7.8) |

28 (14.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Super supermarket |

19 (3.3) |

2 (1.1) |

9 (4.5) |

8 (4.2) |

|

Person to eat together |

|

|

|

|

54.089 |

0.000***

|

|

Alone |

408 (71.6) |

138 (76.7) |

124 (62.0) |

146 (76.8) |

|

Friends |

143 (25.1) |

40 (22.2) |

76 (38.0) |

27 (14.2) |

|

Family |

19 (3.3) |

2 (1.1) |

0 (0.0) |

17 (8.9) |

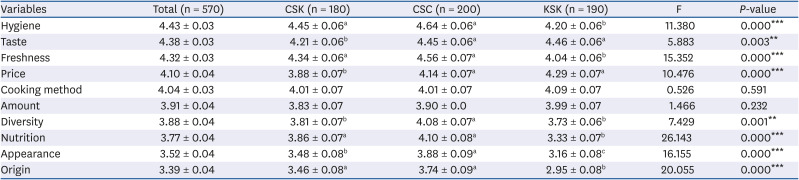

Importance of attributes when selecting home meal replacement

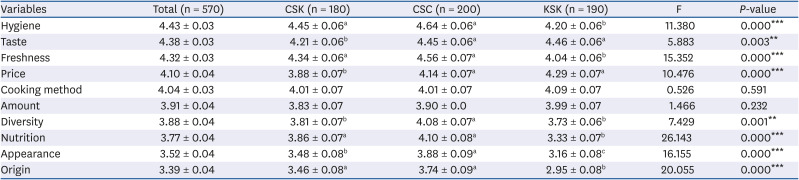

The importance of attributes (taste, freshness, price, etc.) when subjects selected HMR is shown in

Table 3. The average scores of taste (

P < 0.01) and price (

P < 0.001) in the CSC and KSK were significantly higher compared to the CSK, while average scores for freshness, nutrition, hygiene, and origin in the CSK and CSC were significantly higher compared to the KSK (

P < 0.001). The CSC showed higher on diversity and appearance scores than the CSK and KSK. No significant intergroup difference was observed for amount or cooking method. The most important attributes in the CSK and CSC in order were hygiene, freshness, and taste, while in the KSK in order were taste, price, and hygiene. In all 3 groups, the importance scores of origin and appearance were the lowest.

Table 3

Importance of attributes when selecting home meal replacement

|

Variables |

Total (n = 570) |

CSK (n = 180) |

CSC (n = 200) |

KSK (n = 190) |

F |

P-value |

|

Hygiene |

4.43 ± 0.03 |

4.45 ± 0.06a

|

4.64 ± 0.06a

|

4.20 ± 0.06b

|

11.380 |

0.000***

|

|

Taste |

4.38 ± 0.03 |

4.21 ± 0.06b

|

4.45 ± 0.06a

|

4.46 ± 0.06a

|

5.883 |

0.003**

|

|

Freshness |

4.32 ± 0.03 |

4.34 ± 0.06a

|

4.56 ± 0.07a

|

4.04 ± 0.06b

|

15.352 |

0.000***

|

|

Price |

4.10 ± 0.04 |

3.88 ± 0.07b

|

4.14 ± 0.07a

|

4.29 ± 0.07a

|

10.476 |

0.000***

|

|

Cooking method |

4.04 ± 0.03 |

4.01 ± 0.07 |

4.01 ± 0.07 |

4.09 ± 0.07 |

0.526 |

0.591 |

|

Amount |

3.91 ± 0.04 |

3.83 ± 0.07 |

3.90 ± 0.0 |

3.99 ± 0.07 |

1.466 |

0.232 |

|

Diversity |

3.88 ± 0.04 |

3.81 ± 0.07b

|

4.08 ± 0.07a

|

3.73 ± 0.06b

|

7.429 |

0.001**

|

|

Nutrition |

3.77 ± 0.04 |

3.86 ± 0.07a

|

4.10 ± 0.08a

|

3.33 ± 0.07b

|

26.143 |

0.000***

|

|

Appearance |

3.52 ± 0.04 |

3.48 ± 0.08b

|

3.88 ± 0.09a

|

3.16 ± 0.08c

|

16.155 |

0.000***

|

|

Origin |

3.39 ± 0.04 |

3.46 ± 0.08a

|

3.74 ± 0.09a

|

2.95 ± 0.08b

|

20.055 |

0.000***

|

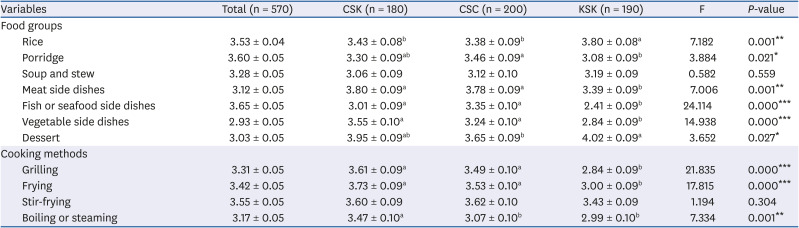

Needs of food groups and cooking methods for home meal replacement development

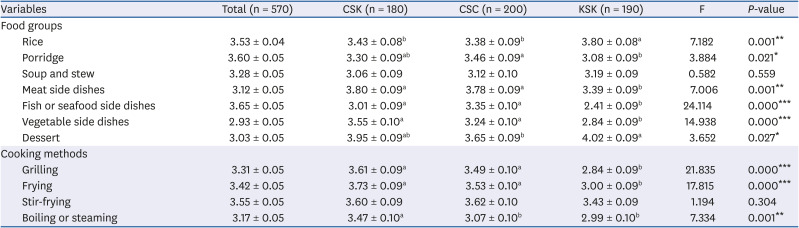

The needs of food groups and cooking methods for HMR development of the subjects are shown in

Table 4. Regarding food groups needed for HMR development, development needs a score for rice in the KSK was significantly higher compared to the CSK and CSC (

P < 0.01), and development needs scores for meats (

P < 0.01), fish or seafood and vegetable (

P < 0.001) side dishes in the CSK and CSC were significantly higher compared to the KSK. The development needs a score for dessert in the CSK and KSK was significantly higher compared to the CSC (

P < 0.05). The food groups with high development needs in order in the three groups were dessert, meat side dishes, and vegetable side dishes in the CSK, meat side dishes, dessert, and porridge in the CSC, and dessert, rice, and meat side dishes in the KSK.

Table 4

Needs of food groups and cooking methods for home meal replacement development

|

Variables |

Total (n = 570) |

CSK (n = 180) |

CSC (n = 200) |

KSK (n = 190) |

F |

P-value |

|

Food groups |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rice |

3.53 ± 0.04 |

3.43 ± 0.08b

|

3.38 ± 0.09b

|

3.80 ± 0.08a

|

7.182 |

0.001**

|

|

Porridge |

3.60 ± 0.05 |

3.30 ± 0.09ab

|

3.46 ± 0.09a

|

3.08 ± 0.09b

|

3.884 |

0.021*

|

|

Soup and stew |

3.28 ± 0.05 |

3.06 ± 0.09 |

3.12 ± 0.10 |

3.19 ± 0.09 |

0.582 |

0.559 |

|

Meat side dishes |

3.12 ± 0.05 |

3.80 ± 0.09a

|

3.78 ± 0.09a

|

3.39 ± 0.09b

|

7.006 |

0.001**

|

|

Fish or seafood side dishes |

3.65 ± 0.05 |

3.01 ± 0.09a

|

3.35 ± 0.10a

|

2.41 ± 0.09b

|

24.114 |

0.000***

|

|

Vegetable side dishes |

2.93 ± 0.05 |

3.55 ± 0.10a

|

3.24 ± 0.10a

|

2.84 ± 0.09b

|

14.938 |

0.000***

|

|

Dessert |

3.03 ± 0.05 |

3.95 ± 0.09ab

|

3.65 ± 0.09b

|

4.02 ± 0.09a

|

3.652 |

0.027*

|

|

Cooking methods |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Grilling |

3.31 ± 0.05 |

3.61 ± 0.09a

|

3.49 ± 0.10a

|

2.84 ± 0.09b

|

21.835 |

0.000***

|

|

Frying |

3.42 ± 0.05 |

3.73 ± 0.09a

|

3.53 ± 0.10a

|

3.00 ± 0.09b

|

17.815 |

0.000***

|

|

Stir-frying |

3.55 ± 0.05 |

3.60 ± 0.09 |

3.62 ± 0.10 |

3.43 ± 0.09 |

1.194 |

0.304 |

|

Boiling or steaming |

3.17 ± 0.05 |

3.47 ± 0.10a

|

3.07 ± 0.10b

|

2.99 ± 0.10b

|

7.334 |

0.001**

|

Regarding cooking methods needed for HMR development, the development needs scores of grilling and frying in the CSK and CSC were significantly higher compared to the KSK (P < 0.001), while the development needs a score of boiling or steaming in the CSK were significantly higher compared to the CSC and KSK (P < 0.01). The cooking methods with the highest development score were frying in the CSK and stir-frying in the CSC and KSK.

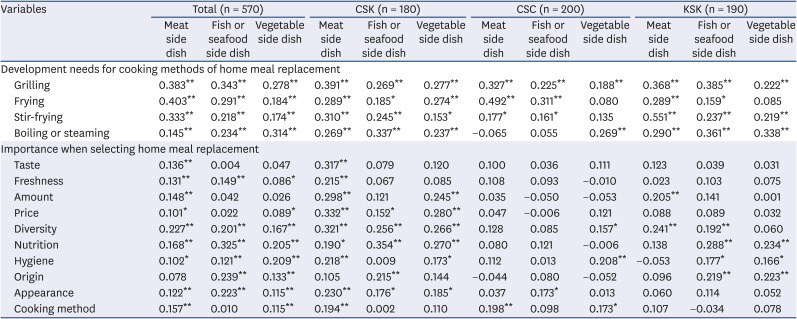

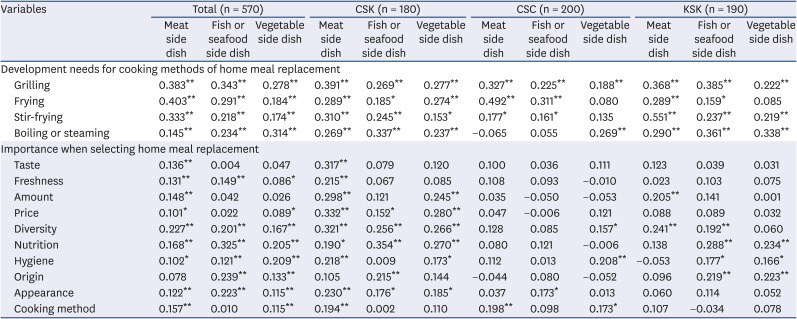

Correlation coefficients among development needs for side dishes of HMR, cooking methods of HMR, and importance when selecting HMR

As shown in

Table 5, all groups showed a significantly positive correlation between the development needs for side dishes and the development needs for cooking methods. The higher the development needs for meat and fish or seafood side dishes, the higher were the development needs for grilling, frying, and stir-frying cooking methods. In addition, the higher the development need for vegetable side dishes, the higher was the development needs for grilling and boiling or steaming cooking methods.

Table 5

Correlation coefficients among development needs for side dishes of HMR, cooking methods of HMR, and importance when selecting HMR

|

Variables |

Total (n = 570) |

CSK (n = 180) |

CSC (n = 200) |

KSK (n = 190) |

|

Meat side dish |

Fish or seafood side dish |

Vegetable side dish |

Meat side dish |

Fish or seafood side dish |

Vegetable side dish |

Meat side dish |

Fish or seafood side dish |

Vegetable side dish |

Meat side dish |

Fish or seafood side dish |

Vegetable side dish |

|

Development needs for cooking methods of home meal replacement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Grilling |

0.383**

|

0.343**

|

0.278**

|

0.391**

|

0.269**

|

0.277**

|

0.327**

|

0.225**

|

0.188**

|

0.368**

|

0.385**

|

0.222**

|

|

Frying |

0.403**

|

0.291**

|

0.184**

|

0.289**

|

0.185*

|

0.274**

|

0.492**

|

0.311**

|

0.080 |

0.289**

|

0.159*

|

0.085 |

|

Stir-frying |

0.333**

|

0.218**

|

0.174**

|

0.310**

|

0.245**

|

0.153*

|

0.177*

|

0.161*

|

0.135 |

0.551**

|

0.237**

|

0.219**

|

|

Boiling or steaming |

0.145**

|

0.234**

|

0.314**

|

0.269**

|

0.337**

|

0.237**

|

−0.065 |

0.055 |

0.269**

|

0.290**

|

0.361**

|

0.338**

|

|

Importance when selecting home meal replacement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Taste |

0.136**

|

0.004 |

0.047 |

0.317**

|

0.079 |

0.120 |

0.100 |

0.036 |

0.111 |

0.123 |

0.039 |

0.031 |

|

Freshness |

0.131**

|

0.149**

|

0.086*

|

0.215**

|

0.067 |

0.085 |

0.108 |

0.093 |

−0.010 |

0.023 |

0.103 |

0.075 |

|

Amount |

0.148**

|

0.042 |

0.026 |

0.298**

|

0.121 |

0.245**

|

0.035 |

−0.050 |

−0.053 |

0.205**

|

0.141 |

0.001 |

|

Price |

0.101*

|

0.022 |

0.089*

|

0.332**

|

0.152*

|

0.280**

|

0.047 |

−0.006 |

0.121 |

0.088 |

0.089 |

0.032 |

|

Diversity |

0.227**

|

0.201**

|

0.167**

|

0.321**

|

0.256**

|

0.266**

|

0.128 |

0.085 |

0.157*

|

0.241**

|

0.192**

|

0.060 |

|

Nutrition |

0.168**

|

0.325**

|

0.205**

|

0.190*

|

0.354**

|

0.270**

|

0.080 |

0.121 |

−0.006 |

0.138 |

0.288**

|

0.234**

|

|

Hygiene |

0.102*

|

0.121**

|

0.209**

|

0.218**

|

0.009 |

0.173*

|

0.112 |

0.013 |

0.208**

|

−0.053 |

0.177*

|

0.166*

|

|

Origin |

0.078 |

0.239**

|

0.133**

|

0.105 |

0.215**

|

0.144 |

−0.044 |

0.080 |

−0.052 |

0.096 |

0.219**

|

0.223**

|

|

Appearance |

0.122**

|

0.223**

|

0.115**

|

0.230**

|

0.176*

|

0.185*

|

0.037 |

0.173*

|

0.013 |

0.060 |

0.114 |

0.052 |

|

Cooking method |

0.157**

|

0.010 |

0.115**

|

0.194**

|

0.002 |

0.110 |

0.198**

|

0.098 |

0.173*

|

0.107 |

−0.034 |

0.078 |

Development needs for meat, fish or seafood, and vegetable HMR side dishes and importance when selecting HMR were positively correlated. For meat side dishes, positive correlations were observed for all variables except origin in the CSK, but the only cooking method in the CSC, and amount and diversity in the KSK. Development needs for fish or seafood side dishes were positively correlated with price, diversity, nutrition, origin, and only appearance in the CSK, appearance in the CSC, and diversity, nutrition, hygiene, and origin in the KSK. For vegetable side dishes, amount, price, diversity, nutrition, hygiene, and appearance were positively correlated with development scores in the CSK, diversity, hygiene, cooking method in the CSC, and nutrition, hygiene, and origin in the KSK.

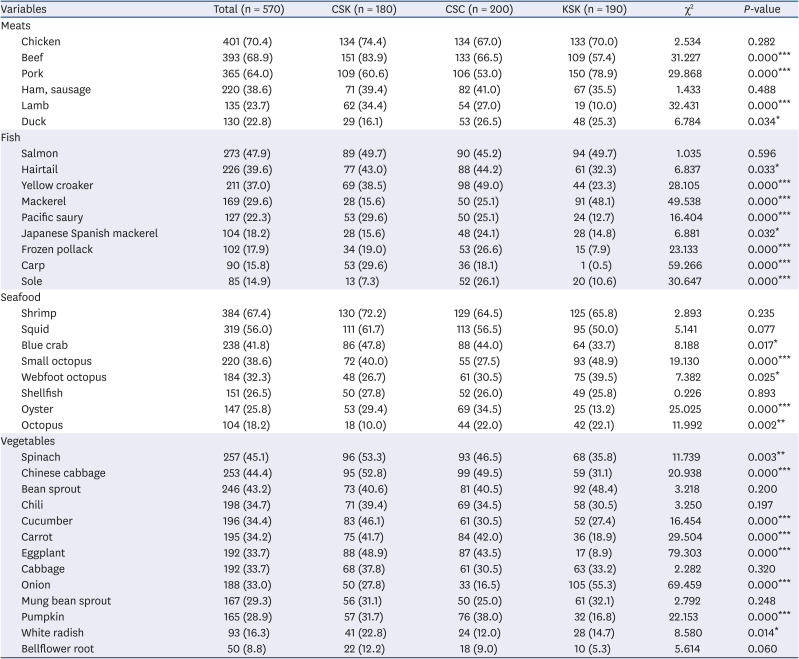

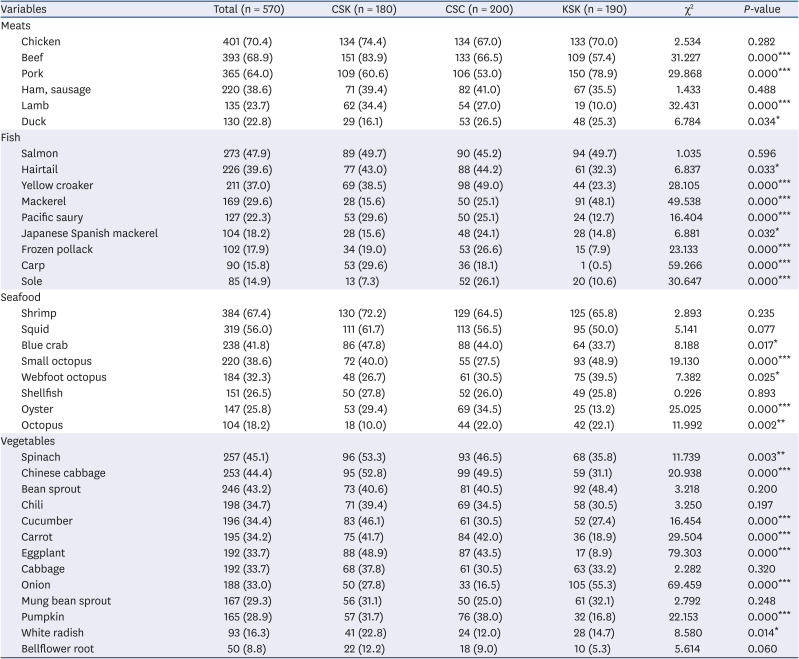

Preferences for food materials

The preferences for meats, fish, seafood, and vegetables of the subject are shown in

Table 6. In the case of meats, more than 50% of subjects in each group preferred beef, pork, and chicken, while the most preferred meats in the CSK, CSC, and KSK were beef, chicken, and pork, respectively. Chicken was a meat with high preference in all groups although no significant difference in intergroup preference was observed, and lamb was less preferred in the KSK compared to other groups (

P < 0.001).

Table 6

Preferences for food materials of the subjects

|

Variables |

Total (n = 570) |

CSK (n = 180) |

CSC (n = 200) |

KSK (n = 190) |

χ2

|

P-value |

|

Meats |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chicken |

401 (70.4) |

134 (74.4) |

134 (67.0) |

133 (70.0) |

2.534 |

0.282 |

|

Beef |

393 (68.9) |

151 (83.9) |

133 (66.5) |

109 (57.4) |

31.227 |

0.000***

|

|

Pork |

365 (64.0) |

109 (60.6) |

106 (53.0) |

150 (78.9) |

29.868 |

0.000***

|

|

Ham, sausage |

220 (38.6) |

71 (39.4) |

82 (41.0) |

67 (35.5) |

1.433 |

0.488 |

|

Lamb |

135 (23.7) |

62 (34.4) |

54 (27.0) |

19 (10.0) |

32.431 |

0.000***

|

|

Duck |

130 (22.8) |

29 (16.1) |

53 (26.5) |

48 (25.3) |

6.784 |

0.034*

|

|

Fish |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Salmon |

273 (47.9) |

89 (49.7) |

90 (45.2) |

94 (49.7) |

1.035 |

0.596 |

|

Hairtail |

226 (39.6) |

77 (43.0) |

88 (44.2) |

61 (32.3) |

6.837 |

0.033*

|

|

Yellow croaker |

211 (37.0) |

69 (38.5) |

98 (49.0) |

44 (23.3) |

28.105 |

0.000***

|

|

Mackerel |

169 (29.6) |

28 (15.6) |

50 (25.1) |

91 (48.1) |

49.538 |

0.000***

|

|

Pacific saury |

127 (22.3) |

53 (29.6) |

50 (25.1) |

24 (12.7) |

16.404 |

0.000***

|

|

Japanese Spanish mackerel |

104 (18.2) |

28 (15.6) |

48 (24.1) |

28 (14.8) |

6.881 |

0.032*

|

|

Frozen pollack |

102 (17.9) |

34 (19.0) |

53 (26.6) |

15 (7.9) |

23.133 |

0.000***

|

|

Carp |

90 (15.8) |

53 (29.6) |

36 (18.1) |

1 (0.5) |

59.266 |

0.000***

|

|

Sole |

85 (14.9) |

13 (7.3) |

52 (26.1) |

20 (10.6) |

30.647 |

0.000***

|

|

Seafood |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shrimp |

384 (67.4) |

130 (72.2) |

129 (64.5) |

125 (65.8) |

2.893 |

0.235 |

|

Squid |

319 (56.0) |

111 (61.7) |

113 (56.5) |

95 (50.0) |

5.141 |

0.077 |

|

Blue crab |

238 (41.8) |

86 (47.8) |

88 (44.0) |

64 (33.7) |

8.188 |

0.017*

|

|

Small octopus |

220 (38.6) |

72 (40.0) |

55 (27.5) |

93 (48.9) |

19.130 |

0.000***

|

|

Webfoot octopus |

184 (32.3) |

48 (26.7) |

61 (30.5) |

75 (39.5) |

7.382 |

0.025*

|

|

Shellfish |

151 (26.5) |

50 (27.8) |

52 (26.0) |

49 (25.8) |

0.226 |

0.893 |

|

Oyster |

147 (25.8) |

53 (29.4) |

69 (34.5) |

25 (13.2) |

25.025 |

0.000***

|

|

Octopus |

104 (18.2) |

18 (10.0) |

44 (22.0) |

42 (22.1) |

11.992 |

0.002**

|

|

Vegetables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spinach |

257 (45.1) |

96 (53.3) |

93 (46.5) |

68 (35.8) |

11.739 |

0.003**

|

|

Chinese cabbage |

253 (44.4) |

95 (52.8) |

99 (49.5) |

59 (31.1) |

20.938 |

0.000***

|

|

Bean sprout |

246 (43.2) |

73 (40.6) |

81 (40.5) |

92 (48.4) |

3.218 |

0.200 |

|

Chili |

198 (34.7) |

71 (39.4) |

69 (34.5) |

58 (30.5) |

3.250 |

0.197 |

|

Cucumber |

196 (34.4) |

83 (46.1) |

61 (30.5) |

52 (27.4) |

16.454 |

0.000***

|

|

Carrot |

195 (34.2) |

75 (41.7) |

84 (42.0) |

36 (18.9) |

29.504 |

0.000***

|

|

Eggplant |

192 (33.7) |

88 (48.9) |

87 (43.5) |

17 (8.9) |

79.303 |

0.000***

|

|

Cabbage |

192 (33.7) |

68 (37.8) |

61 (30.5) |

63 (33.2) |

2.282 |

0.320 |

|

Onion |

188 (33.0) |

50 (27.8) |

33 (16.5) |

105 (55.3) |

69.459 |

0.000***

|

|

Mung bean sprout |

167 (29.3) |

56 (31.1) |

50 (25.0) |

61 (32.1) |

2.792 |

0.248 |

|

Pumpkin |

165 (28.9) |

57 (31.7) |

76 (38.0) |

32 (16.8) |

22.153 |

0.000***

|

|

White radish |

93 (16.3) |

41 (22.8) |

24 (12.0) |

28 (14.7) |

8.580 |

0.014*

|

|

Bellflower root |

50 (8.8) |

22 (12.2) |

18 (9.0) |

10 (5.3) |

5.614 |

0.060 |

In the case of fish, salmon, hairtail, and yellow croaker were most preferred in the CSK and CSC, while salmon, mackerel, and hairtail were most preferred in the KSK. Preferences for hairtail, pacific saury, and sole in the CSK and CSC were significantly greater than in the KSK. However, the preference for fish was less than 50% in all groups, and the preference for fish in the subjects was lower than that for other foods.

In the case of seafood, shrimp and squid were preferred in all groups more than 50% in each group. Proportions that preferred octopus were significantly higher in the CSC and KSK than in the CSK (P < 0.01), and proportions that preferred oyster and blue crab in the CSK and CSC were significantly higher than that in the KSK (P < 0.05).

In the case of vegetables, the CSK and CSC preferred spinach, Chinese cabbage, and eggplant, where the KSK preferred onions, bean sprouts, and spinach. Preferences for carrot, pumpkin, Chinese cabbage, eggplant, and cucumber in the CSK and CSC were significantly higher than in the KSK.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Chinese college students account for the greatest proportion of foreign college students studying abroad in Korea, and HMR consumption by Korean and Chinese college students is increasing. This study was conducted to compare the HMR consumption behaviors and HMR development needs and food preferences among the CSK, CSC, and KSK.

Regarding HMR consumption behaviors, the CSK and CSC used HMR in order breakfast, lunch, or dinner substitutes, whereas KSK used them as snack, lunch, or dinner substitutes (

P < 0.001). The reasons for purchasing HMR were ‘saving time’ and ‘preventing meal skipping’ in all 3 groups. According to previous studies [

3031] in college students in Korea and China, self-boarding college students skip breakfast more frequently and eat faster than college students living in a dormitory or living with a family. Kim

et al. [

32] reported that the frequency of processed food intake in self-boarding Korean college students was higher than for those living in other types of residences, and their preferred processed foods were confectionery, retort pouch, and convenience food, which correspond to RTC and RTH. Residence types differed in the three study groups; that is 62.2% of the CSK were self-boarding, 76.0% of the CSC lived in dormitories, and 48.4% and 42.1% of the KSK lived with families or self-boarded, respectively. The CSK was a higher consumption proportion of HMR as meal substitutes than the KSK, and thus, the self-boarding CSK needs HMR that can be easily consumed. Also, Chinese college students have regular lunchtimes, whereas Korean college students do not [

33], and it has been previously reported a meal substitute that can be consumed in a short time is required for the KSK and foreign college students studying in Korea [

34]. Therefore, a simple, convenient RTC or RTE with plenty of nutrients in one meal is needed to reduce the frequency of skipping meals and provide a regular meal for the CSK.

In this study, HMR was purchased by the CSK and KSK mainly at convenience stores, and the CSC mainly purchased at convenience stores and shopping malls (

P < 0.001). The home shopping market on Chinese TV has about 5 times as many channels as in Korea, and the Chinese are familiar with the shopping mall delivery culture [

35]. However, convenience stores are used more than shopping malls by the CSK, because the number of convenience stores in Korea is about 30 times larger than in China in terms of numbers of units per unit area [

36] and convenience stores are more accessible than large supermarkets and department stores around college campuses. It has been reported that 23.1% of foreign college students in Korea used convenience store foods more than five times a week [

10], and thus, consumption of convenience store food may affect the frequency of daily meal intake. Korean and Chinese college students are most likely purchase HMR such as RTE and RTH products through convenience stores or shopping malls (Internet and TV), so when they choose HMR products, it is important to consider nutrients content (protein, sodium, sugar, and trans fat, etc.). In addition, it is desirable to eat salads with vegetables and fruits to supplement minerals and vitamins that are likely to be lacking nutrients in convenience store lunchboxes. For that, it is suggested that nutritionally balanced HMR development and nutrition education and guidance for Korean and Chinese college students are necessary.

Lunchboxes consisting mainly of rice and side dishes are representative of HMRs found in Korean convenience stores and is sold for 4,000 to 8,000 won. However, in China, a representative HMR found in convenience stores might consist of fried rice with toppings, which is sold for 6 to 20 yuan (about 1,020 to 3,500 won/1 yuan = 171 won) [

37]. Comparison based on the convenience store lunchboxes, it can be seen that the average purchase price for HMR is similar to the results of this study, with CSK and KSK of 3,000 to 10,000 won and CSC of less than 3,000 to 5,000 won, and those in Korea were more expensive than those in China. However, in terms of frequencies of HMR consumption observed in this study, 61.7% in the CSK and 48.0% in the CSC consumed HMR 1–2 times a week, while 6.1% in the CSK and 11.0% in the CSC consumed HMR more than 5 times a week. In other words, the CSK showed a tendency for low frequency of HMR consumption compared to the CSC. In a study by Wang

et al. [

5], 84% of Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea consumed Chinese food in Korea, 56.5% cooked food themselves and 31.5% purchased food. Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea who found Korea culture adaptation stressful reported a higher rate of Chinese food consumption [

38]. This indicates that although the CSK wants to reduce cooking preparation time, they buy fewer units because of a lack of HMR with a suitable taste and because they are relatively expensive. Therefore, new products favored by young Chinese should be developed by benchmarking popular HMR in China and by researching the preferences for HMR in Korea. In addition, it is considered that the development of the cheap HMR (such as RTC type called meal-kits) composed of Chinese menus will help Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea to cook easily and eat Chinese food, thereby reducing the stress associated with adapting to life in Korea.

The importance of purchasing attributes, preferred food types, and cooking methods were investigated to compare the development needs of the three groups for HMR. When selecting HMR, taste and price were more important to the CSC and KSK than to the CSK, whereas freshness, nutrition value, hygiene, and origin of food were more important to the CSK and CSC than the KSK. In addition, although there were differences among the 3 groups, the priorities of the CSK and CSC were in order hygiene, freshness, and taste, while those of the KSK were taste, price, and hygiene. A previous study [

29] on the priorities of HMR selection attributes of Korean college students also ranked taste, price, convenience, and safety in order. Na’s study [

39] showed that the priority of HMR selection by Korean and Chinese adults showed 41.2% of Koreans considered taste and 40.5% of Chinese considered hygiene first priorities. China has experienced many food safety accidents, and as a result, food safety-related law ‘Food Production Permit Management Measure (食品生产许可管理办法)’ was revised in 2015. This law requires that food manufacturers guarantee food quality. However, despite full enforcement of this law from October 2018, consumer trust has not been restored due to insufficient government measures and the concealment of safety-related incidents. Therefore, when developing HMR for the CSK, hygiene and freshness need to be given special consideration and promoted.

As a result of investigating the development needs of HMR, we found the development needs for rice-based products by the CSK and CSC were significantly lower those of the KSK. However, the development needs of meat, fish, seafood, and vegetable side dishes and cooking methods such as stir-frying and frying were significantly higher among the CSK and CSC than in the KSK. Preferences for meat, fish, seafood, and vegetable-based HMR that can be used as side dishes showed similar patterns for the CSK and CSC [

40], and these differed from the KSK preferences. Since Korean food is based on rice culture and Chinese food is based on stir-fried cooking, it seems to be a phenomenon that emerges from traditional cultural differences.

According to our preference survey on meat, the CSK and CSC showed a high preference for beef, while the KSK preferred pork; the CSK and CSC showed the lowest preference for duck meat. A previous study [

4142], which investigated the preference of food materials used in Korean food for Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea, produced the same result with the highest preference for beef and the lowest preference for duck. In addition, previous studies [

264344], which investigated Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea preferences for Korean food have reported Korean food menus based on beef, such as

bulgogi, neobiani, galbijjim, and

galbitang, are highly preferred. Lamb, which was more highly preferred by the CSK than the KSK, has also recently become so popular in Korea that lamb meat restaurant streets now exist. In addition to grilling, a new type of RTH based on other cooking methods, such as stir-frying, boiling, stewing, and steaming, that can be eaten not only by the CSK but also by the KSK is needed. However, beef or lamb based HMR raise cost considerations, given that prices should be accessible by the CSK and KSK.

In the case of fish, salmon was highly preferred by all groups. The CSK and CSC preferences for hairtail, pacific saury, and carp were significantly higher than those of the KSK, which concurs with the findings of a previous study on the CSK preferences [

41]. However, in all 3 groups of the present study, preference for fish was less than 50%, and seafood was preferred to fish.

As regards seafood, preference of shrimp and squid was highest in all groups, which agrees with the result of a previous survey [

42]. Recently in Korea, Chinese food such as

Maralongsha (spicy shrimp dish) and

Maratang have become popular around college towns. Shrimp and squid are used in various ways in HMR of both countries in grilled or fried forms. However, in Korea, few Chinese dishes are available as HMR. Inexpensive Chinese dish based HMR containing seafood is required because it being difficult for college students to wash and cook.

In the case of vegetables, the CSK and CSC preferred spinach and Chinese cabbage most, while the KSK most preferred onions. In addition, the CSK had high preferences for pumpkins, eggplants, cucumbers, and white radish, which concurs with a previous study on Korean food preferences for the Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea [

41]. Vegetables are eaten in Korea raw, boiled, or steamed, whereas in China they are cooked using a dry-heat method (e.g., grilling or frying), but Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea longer eat more raw and boiled vegetables [

45]. In addition, it was reported that the frequency of vegetable intake decreased after the Chinese college students moved to Korea [

4] and 60–70% of Chinese college students studying abroad in Korea were below the recommended intake in vitamins A, B

2, C, zinc, folic acid, and calcium intakes [

46]. Therefore, it appears that vegetable side dish HMR of dietary types should be developed.

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, since this study is a cross-sectional study of studying abroad and local college students in some regions of Korea and China, it is difficult to generalize. Second, although the translated questionnaire was verified using preliminary surveys several times, there are limitations regarding the equivalences of meanings as understood by Koreans and Chinese. Despite these limitations, this study was meaningful in terms of the consumption behaviors and HMR development needs of the CSK, CSC, and KSK.

In summary, our findings suggest customized HMR be developed for the CSK, CSC, and KSK based on considerations of national food culture and preferred product types. Therefore, it considers that the CSK needs a variety of hygienic, fresh HMR, the CSC needs meat side dishes that are hygienic and cheap, and the KSK needs a snack type meal substitute that is tasty and cheap. In particular, the lives of the CSK would be enhanced by fresh and balanced food-based HMR, which fully considers nutritional aspects.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download