Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), mainly spread through droplets and is known to be spreadable through aerosols in particular circumstances.

1 In a healthcare setting, hospitalized patients are more likely to be elderly with multiple comorbidities, so the risk of developing severe COVID-19 is high,

2 and healthcare personnel (HCP) may serve as reservoirs, vectors, or victims of SARS-CoV-2 transmission between hospitals and communities.

3 Therefore, preventing the nosocomial spread of SARS-CoV-2 is essential, but it is challenging.

To evaluate the preventive measures for the potential exposure events of COVID-19 in the hospital, we retrospectively reviewed all in-hospital COVID-19 exposure events from January 19, 2020 to June 15, 2021, at a tertiary hospital located in Seoul, Korea. The study hospital is a 1,761 bed university-affiliated tertiary hospital with over 8,600 HCP, including 1,947 doctors and 2,916 nurses, and treats about 540,000 inpatients and 2,230,000 outpatients annually.

4 The study period was from the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea to the completion of vaccination for the most HCP at the study hospital. When HCP were accidentally exposed to confirmed SARS-CoV-2 patients in the hospital, the level of risk was assessed through epidemiological investigation by national guidelines. Then, one of the preventive measures among passive monitoring, active monitoring, and self-quarantine, was applied to the HCP based on the level of the risk, and the final action was decided by the head of the local public health center. For the passive monitoring group, HCP self-assessed their symptoms and received SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) selectively. We checked their symptoms twice daily for the active monitoring group and recommended SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR, but performed selectively. We also applied work restrictions for some of the active monitoring group, of which duration was determined case by case. The HCP in the self-quarantine group were restricted from working for 2 weeks after the last exposure.

During the study period, a total of 203 in-hospital COVID-19 exposure events occurred. The occurrence of the exposure events showed a similar trend to the number of daily confirmed cases in Korea (

Fig. 1).

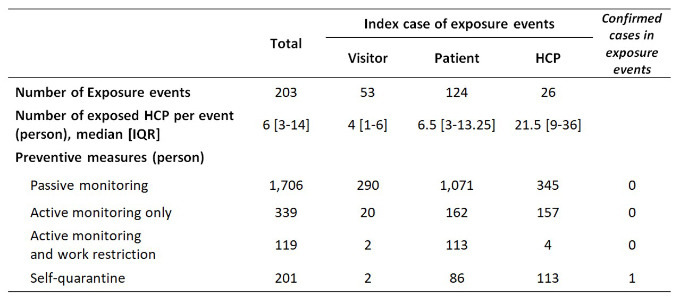

5 Of 203 index cases, 124 (61.1%) were patients, followed by 53 (26.1%) visitors, and 26 (12.8%) HCP. Due to the events, a total of 2,365 HCP were potentially exposed to COVID-19 and preventive measures were applied; 1,706 (72.1%) passive monitoring, 339 (14.3%) active monitoring only, 119 (5.0%) active monitoring with work restriction, and 201 (8.5%) self-quarantine. Total work loss from the restriction was 3,311 person-days.

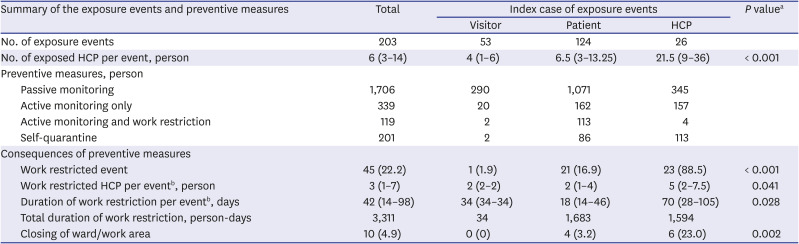

Of 203 exposure events, 45 events resulted in HCP work restrictions, and the index case was HCP or patient except for one case of which the index case was a visitor. There was a significant difference in the possibility of HCP work restrictions depending on the index case (16.9% in the patient index vs. 88.5% in the HCP index,

P < 0.001). From 23 events with HCP index, a total of 117 (median, 5; IQR, 2–7.5 per event) HCP was work-restricted, and total work loss was 1,594 person-days (median 70, IQR 28-105 per event). From 21 events with patient index, a total of 199 (median, 2; IQR, 1–4 per event) HCP were work-restricted, and total work loss was 1,683 person-days (median, 18; IQR, 14–46 per event). When the index cases were HCP, more HCP were work-restricted (5 vs. 2,

P = 0.041), for longer duration (70 person-days vs. 18 person-days,

P = 0.028). Furthermore, in 10 events, exposed places such as the general ward, intensive care unit, emergency room, and chemotherapy daycare center were closed due to a shortage of HCP. It resulted in considerable catastrophic consequences such as delays in treatment for emergency patients and delays in chemotherapy for cancer patients. For example, when a surgeon was confirmed to COVID-19, 11 surgeons were removed from work for 14 days due to preventive measures. As a result, operation room was partially closed for 14 days, and 16 cancer surgeries were canceled or postponed. Summary of exposure events statistics is presented in

Table 1.

Only one confirmed case was presumed to be infected by in-hospital exposure to SARS-CoV-2 from the self-quarantine group. The confirmed case was a doctor, classified as a self-quarantine group after his co-worker confirmed to COVID-19. He used the same room without wearing a mask with the index case a half to an hour every day. He was asymptomatic but confirmed with COVID-19 13-days after the last exposure, which was one day before the date of the confirmed date of his co-worker, during the self-quarantine period.

There is no doubt that preventing the nosocomial spread of SARS-CoV-2 is essential. SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted from people without symptoms, and one modeling study found that more than half of all transmissions were from asymptomatic individuals.

6 Therefore, a more conservative approach to HCP monitoring and applying work restriction is recommended. However, when implementing public health measures, we also consider its effectiveness, proportionality, necessity, and least infringement.

7

Our study might suggest that the risk of transmission from patients with COVID-19 to HCP is low when HCP followed general infection control principles. In the previous studies, frontline HCP with appropriate personal protective equipment did not appear to be at higher risk of COVID-19,

8 and there was no transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from patients in hundreds of close contacts including aerosol-generating procedures,

910 which is consistent with our findings. Hence, it is questionable whether excessively taken preventive measures are effective. Furthermore, preventive measures for HCP might have been taken beyond the national guideline, probably due to excessive fear for a nosocomial outbreak, desire to avoid responsibility, and difficulty assessing the risk of exposure.

In the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are negative impacts not only on COVID-19 patients but also on non-COVID-19 patients.

1112 Causes of this impact are multifactorial, but lack of medical resources is one of them. In the case of significant exposure events in our experience, many HCP were work-restricted simultaneously, and wards and emergency rooms were closed, drawing delays in the provision of critical medical care such as managing emergent patients and chemotherapy for cancer patients. From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, large hospitals in Korea experienced a shortage of staff and partial to complete closure due to nosocomial COVID-19 infection,

13 and there have been concerns about extreme preventive measures.

14 Although the damage caused by extreme preventive measures is not directly visible; it may exceed the benefit of preventing the nosocomial spread of SARS-CoV-2.

In this study, the impacts of in-hospital COVID-19 exposure events were more significant when the index case was HCP compared to other cases. This seems to be because HCP followed the recommended routine infection prevention and control practices including wearing appropriate personal protective equipment while caring for patients, but there were more situations where HCP could not wear a mask, such as eating and drinking while socializing with their colleagues. Therefore, to reduce the adverse impact caused by potential exposure event of COVID-19 in hospital, it is necessary to create an environment in which HCP can adhere to the recommendation such as universal masking.

Increasing vaccination coverage among HCP might diminish the adverse impact of COVID-19 exposure events in a healthcare setting. Recent guidelines suggested that asymptomatic HCP who have had a higher-risk exposure do not require work restriction if they have been fully vaccinated.

15 However, the emergence of variant strain and the possibility of breakthrough infection remind us that the preventive measures in healthcare setting should not rely solely on vaccines, and we should seek the balanced preventive measures. According to some published reports, secondary infection from non-isolated patients with COVID-19 to HCP not wearing recommended personal protective equipment is low, especially when the contact time is less than an hour.

10161718192021 Therefore, relaxing criteria of close contact may be one way, and continuous effort to find an additional way is necessary.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective, single-center (with hospital-specific infection control guidelines) study in a low prevalence country, so generalization is limited. Second, SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR was not performed in all passive and active monitoring cases, so there is a possibility of missing asymptomatic infection.

In conclusion, current preventive measures after in-hospital COVID-19 exposure events might be excessive compared to its benefit and establishing stricter standards of work restriction may benefit both HCP and patients.

Ethics statement

The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. 2106-191-1231). Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download