Strategies to tackle latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) have been underscored worldwide and implemented in countries with both low- and high-tuberculosis (TB) burdens.

1 An estimated pool of LTBI was one-fourth of world's population.

2 For TB elimination to incidence of less than one case per million population by 2050, preventing new infection and reducing the preexisting pool of LTBI are crucial, in addition to control active TB cases.

3

The TB burden in South Korea is disproportionately high, considering the high level of socioeconomic development.

4 Before early 2000's, screening and treatment of LTBI were not feasible in South Korea. In 2004, LTBI screening was implemented for people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and family contacts under 6 years of age.

5 Nationwide contact investigation in both household and congregate environment was launched in 2013. However, as several TB outbreaks at hospitals, daycare centers, schools and military units continuously occurred and became important social issues, Korean government implemented ‘TB-free Korea’ program in 2016. In this program, one of the key strategies was to provide screening and treatment of LTBI among more than 1.6 million individuals in congregate settings. The aim of this study was to identify the LTBI test uptake rate and describe demographic profiles of participants who received interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA).

Study settings, methods of data collection and linkage were described in our protocol article.

6 In 2017 and 2018, workers at the prespecified congregate settings underwent LTBI testing (either IGRA or tuberculin skin test [TST]). The source population of each congregate settings were quoted from the 2017's annual survey of government for the number of employees of social welfare institutions, daycare centers, educational institutions, healthcare institutions, postpartum care centers.

789 Total number of first year students in high-school and the average of daily number of inmates in nationwide correctional facility in 2017 were also cited from the official reports of government.

710 Statistics on ‘out-of-school youth’ were not available, so estimated target number of screening replaced the actual number in that group. Because data of participants with negative LTBI results during their military draft health checkup were not available, candidates for military conscripts were excluded in this analysis.

Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) collected baseline demographic information of participants and LTBI test results. These participants constituted a prospective cohort named ‘TB FREE COREA.’ The cohort was matched with National Health Information Database (NHID).

11 Information about income level and place of residence were extracted from the insurance qualification database of NHID. Korean National TB Surveillance System (KNTSS) database was also linked with the cohort to exclude participants with previous TB history and identify the incident TB cases. In addition, to identify an exposure to TB before or after the screening, the national database of TB epidemiological investigation in congregate settings and that in household contacts were also matched with the cohort. Because of high bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination rate in South Korea,

12 we concerned about possible discrepancies between IGRA and TST results

13 and thus excluded participants who underwent only TST. The statistical analyses were performed with descriptive statistics, using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

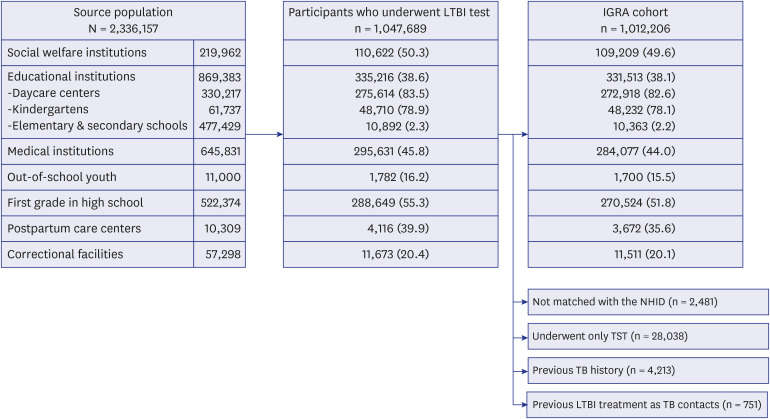

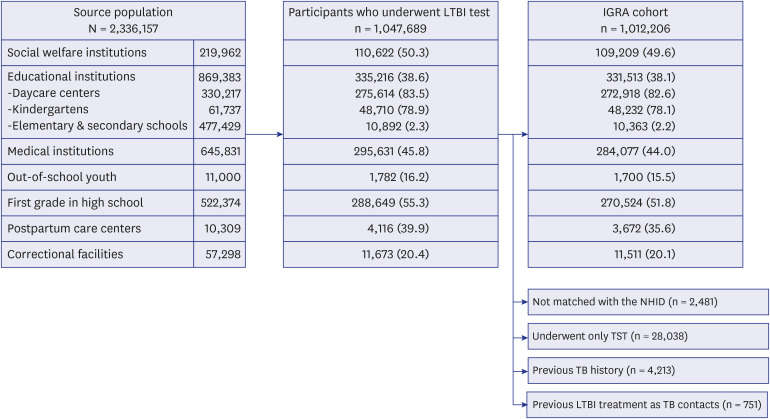

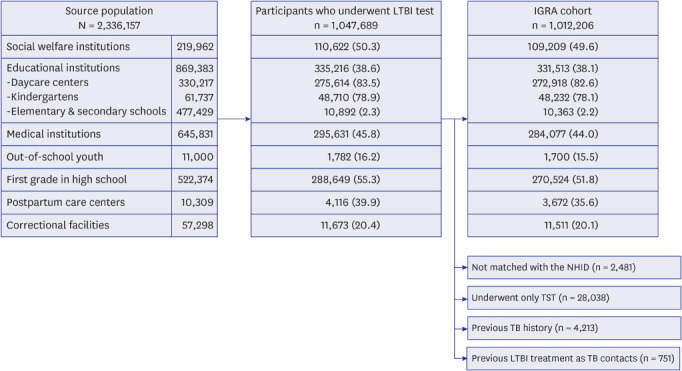

A total of 1,047,689 individuals of 2,336,157 source population underwent either TST or IGRA. The LTBI test uptake rate was 44.8% (

Fig. 1). Workers of daycare centers (83.5%) and kindergartens (78.9%) showed the highest, followed by first year students in high school (55.3%) and workers of social welfare institutions (50.3%). After exclusion of individuals who were not matched with the NHID (n = 2,481), those who underwent only TST between 2017 and 2018 (n = 28,038), those with past TB history (n = 4,213) and those who underwent LTBI treatment as TB contacts before the participation in ‘TB-free Korea’ program (n = 751), a total of 1,012,206 individuals with valid results of IGRA were selected to constitute the IGRA cohort.

| Fig. 1

Flow chart showing the process of IGRA cohort constitution. Number of source population, participation rate of LTBI testing and that of IGRA by each congregate setting were presented.

IGRA = Interferon-gamma release assay, LTBI = latent tuberculosis infection, TST = tuberculin skin test, NHID = National Health Information Database, TB = tuberculosis.

|

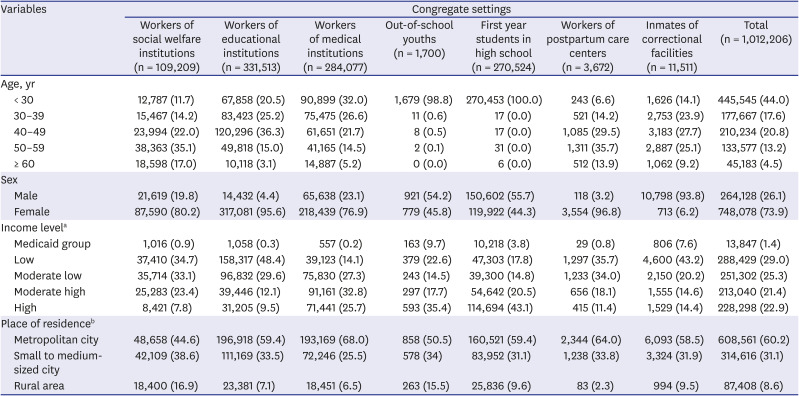

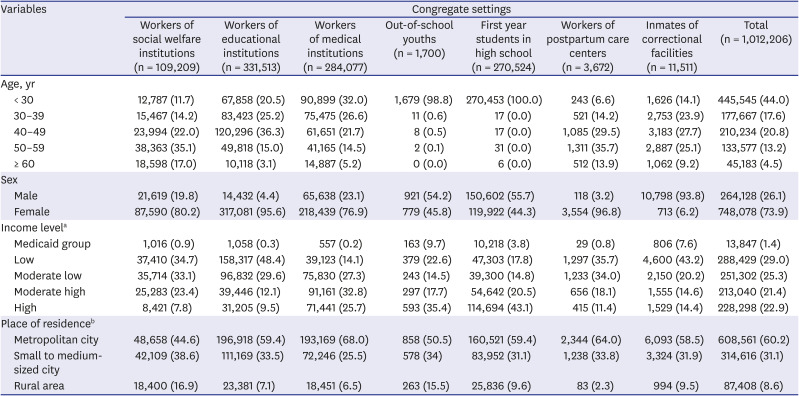

Baseline demographic features of the IGRA cohort were presented in

Table 1. As this screening was carried out among the employees of congregate facilities, most of the enrolled participants were of working age. People in their 50s accounted for the largest proportion among the workers of social welfare institutions and those of postpartum care centers, whereas those in their 20s among the workers of medical institutions. Except for the inmates of correctional facilities, in which the proportion of male was 93.8%, female accounted for three-quarters of total enrolled population among the workers of other congregate facilities. Among the workers of medical institutions and groups of youth, proportion of high-income group was higher than that of other groups.

Table 1

Baseline demographic features of participants enrolled in IGRA cohort

|

Variables |

Congregate settings |

|

Workers of social welfare institutions (n = 109,209) |

Workers of educational institutions (n = 331,513) |

Workers of medical institutions (n = 284,077) |

Out-of-school youths (n = 1,700) |

First year students in high school (n = 270,524) |

Workers of postpartum care centers (n = 3,672) |

Inmates of correctional facilities (n = 11,511) |

Total (n = 1,012,206) |

|

Age, yr |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

< 30 |

12,787 (11.7) |

67,858 (20.5) |

90,899 (32.0) |

1,679 (98.8) |

270,453 (100.0) |

243 (6.6) |

1,626 (14.1) |

445,545 (44.0) |

|

30–39 |

15,467 (14.2) |

83,423 (25.2) |

75,475 (26.6) |

11 (0.6) |

17 (0.0) |

521 (14.2) |

2,753 (23.9) |

177,667 (17.6) |

|

40–49 |

23,994 (22.0) |

120,296 (36.3) |

61,651 (21.7) |

8 (0.5) |

17 (0.0) |

1,085 (29.5) |

3,183 (27.7) |

210,234 (20.8) |

|

50–59 |

38,363 (35.1) |

49,818 (15.0) |

41,165 (14.5) |

2 (0.1) |

31 (0.0) |

1,311 (35.7) |

2,887 (25.1) |

133,577 (13.2) |

|

≥ 60 |

18,598 (17.0) |

10,118 (3.1) |

14,887 (5.2) |

0 (0.0) |

6 (0.0) |

512 (13.9) |

1,062 (9.2) |

45,183 (4.5) |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male |

21,619 (19.8) |

14,432 (4.4) |

65,638 (23.1) |

921 (54.2) |

150,602 (55.7) |

118 (3.2) |

10,798 (93.8) |

264,128 (26.1) |

|

Female |

87,590 (80.2) |

317,081 (95.6) |

218,439 (76.9) |

779 (45.8) |

119,922 (44.3) |

3,554 (96.8) |

713 (6.2) |

748,078 (73.9) |

|

Income levela

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medicaid group |

1,016 (0.9) |

1,058 (0.3) |

557 (0.2) |

163 (9.7) |

10,218 (3.8) |

29 (0.8) |

806 (7.6) |

13,847 (1.4) |

|

Low |

37,410 (34.7) |

158,317 (48.4) |

39,123 (14.1) |

379 (22.6) |

47,303 (17.8) |

1,297 (35.7) |

4,600 (43.2) |

288,429 (29.0) |

|

Moderate low |

35,714 (33.1) |

96,832 (29.6) |

75,830 (27.3) |

243 (14.5) |

39,300 (14.8) |

1,233 (34.0) |

2,150 (20.2) |

251,302 (25.3) |

|

Moderate high |

25,283 (23.4) |

39,446 (12.1) |

91,161 (32.8) |

297 (17.7) |

54,642 (20.5) |

656 (18.1) |

1,555 (14.6) |

213,040 (21.4) |

|

High |

8,421 (7.8) |

31,205 (9.5) |

71,441 (25.7) |

593 (35.4) |

114,694 (43.1) |

415 (11.4) |

1,529 (14.4) |

228,298 (22.9) |

|

Place of residenceb

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Metropolitan city |

48,658 (44.6) |

196,918 (59.4) |

193,169 (68.0) |

858 (50.5) |

160,521 (59.4) |

2,344 (64.0) |

6,093 (58.5) |

608,561 (60.2) |

|

Small to medium-sized city |

42,109 (38.6) |

111,169 (33.5) |

72,246 (25.5) |

578 (34) |

83,952 (31.1) |

1,238 (33.8) |

3,324 (31.9) |

314,616 (31.1) |

|

Rural area |

18,400 (16.9) |

23,381 (7.1) |

18,451 (6.5) |

263 (15.5) |

25,836 (9.6) |

83 (2.3) |

994 (9.5) |

87,408 (8.6) |

Main goal of the ‘TB-free Korea’ program was to protect younger generation from TB, by direct screening themselves, or by screening the potential source of TB transmission to them—workers of postpartum care centers, social welfare institutions, daycare centers, kindergartens and schools. Considering the large generation gap in TB burden, protecting younger generation from TB should be a key strategy for national TB control program in South Korea, which could reduce TB burden drastically within 10 to 20 years. Historically, younger generation was the main target of national LTBI screening programs.

14 In the United States (US), since the efficacy of isoniazid preventive therapy was demonstrated in 1960's,

15 the government implemented massive LTBI screening program with TST which targeted mainly for younger generations such as periodic school-based TST.

16 After decrement of TB incidence in the US, selective screening for high-risk groups was recommended officially by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1995

17 and by American Thoracic Society in 1999.

18 In Japan, since the isoniazid preventive therapy was introduced in 1965, LTBI screening for children 4 years of age, those who entered elementary schools or middle schools was carried out, as in the US.

1920 Since 2005, as the TB burden in Japan had drastically decreased, strategy of mass screening was terminated and selective screening for high-risk groups was adopted.

21

In ‘TB-free Korea’ program, mass screening in two congregate settings—high schools and military units were carried out. Considering that entrance rate of high school in 2017 was 93.7%,

22 approximately half of the population born in the same year underwent LTBI screening. Additionally, although not included in this study, almost all the male population born in another same year underwent LTBI screening as a medical check-up in the military conscription. The long-term effect of such massive LTBI screening will be investigated in individual and community's perspectives.

It is noteworthy that high-risk congregate settings were selected not only for the individual's net benefit, but also for the potential risk of secondary TB cases from a population perspective. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends an individual-level approach in LTBI screening and treatment in low incidence countries.

23 Only in cases that benefit outweigh the risk of treatment such as contacts or people living with HIV, screening and treatment was recommended. However, according to a recently published study, the WHO's recommendation could only protect 4.2% of notified TB cases in Canada, which indicated that such approach would minimally impact national TB burden.

24 Recently in low incidence countries, target groups for screening and treatment of LTBI were expanded considering the countries' epidemiologic status, in which benefit in individual level was limited but that in population level was demonstrated.

25 Hospitals and correctional facilities were well-known high-risk congregate settings,

26272829 whereas postpartum care centers, daycare centers, kindergartens, and schools were not included in high-risk congregate settings in previous guidelines. Selection of such congregate settings was based on a cost-effectiveness analysis,

30 but there were many limitations due to lack of preceding evidence needed for cost-effectiveness analysis. Impact of this screening program on the TB burden in South Korea, especially among the young generation, should be evaluated at the population level.

In this program, only 44.8% of source population underwent LTBI test. However, due to the limited budget of Korean government, the number of actual target population that Korean government had set was 985,000 after exclusion of candidates for military conscription (n = 670,000). Considering that actual goal, we identified that the actual participation rate was more than 100%. We speculated that this full achievement might result from the revised Tuberculosis Prevention Act which ordered the mandatory LTBI screening among this source population since 2016.

This is an unprecedentedly large-scaled population-based LTBI study in South Korea. Except for some groups of young generation, people in various age group were included. The effect of age on prevalence of LTBI, which was the most important predictors for LTBI in a previous population-based survey,

31 and effects of other factors will be investigated. The adherence to the program, which should be warranted for cost-effectiveness of the screening program,

32 will be evaluated in the frame of LTBI cascade of care. Additionally, this cohort contains more than one million IGRA results as quantitative values, not only as binary outcomes. According to the recent research assessing the usefulness of quantitative values of IGRA results,

333435 we will demonstrate the value of quantitative IGRA in prediction of active TB disease and efficacy of LTBI treatment. Based on future analysis of the IGRA cohort, it is feasible to prepare and implement more evidence-based LTBI strategies, which may contribute to TB elimination in South Korea.

Ethics statement

The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Incheon St. Mary's Hospital, the Catholic University of Korea (IRB No. OC19ZESE0023). Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency collected informed consent of all participants when they were enrolled according to Tuberculosis Prevention Act.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download