During the Jeju 4·3 incident (1948–1954), many civilians died because they became embroiled in an armed conflict and suppression of resistance. This is one of the most destructive episodes in modern Korean history, and an estimated 14,000–30,000 innocent people (approximately 10–15% of the population of Jeju Island at the time) were massacred, and hundreds of villages were destroyed on the island.

1 Two recent studies have explored the long-term psychological outcomes of the Jeju 4·3 incident, and found that aged people suffered from psychological sequelae attributable to the extreme stress experienced as children or adolescents.

23 Although such early life trauma may be a risk factor for various psychiatric conditions, including depression, suicidality, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), some persons adapt to such traumatic events, with little disruption after a transient symptomatic period, and subsequently function quite successfully.

45 “Resilience” refers to the ability to thrive in the face of adversity, and the capacity to effectively negotiate, adapt to, or manage significant trauma.

6 Resilience has recently been recognized as one of the most important factors to explore when assessing adjustment after trauma. It has been suggested that demographic variables,

7 including being a man and higher education level, psychological factors such as psychiatric symptoms and life satisfaction,

89 and various socio-contextual factors such as supportive relationships, community resources, and perceived psychosocial support,

10 are associated with resilience. Of these, psychological and socio-contextual factors (including psychiatric symptoms, positive coping behaviors, and psychosocial support) are potentially modifiable.

We investigated the demographic and psychological characteristics of highly resilient older people exposed to the Jeju 4·3 incident. Our study could help identify modifiable factors among individuals with low resilience, and may facilitate the design of resilience-enhancing interventions for older people who experienced early life trauma.

Persons exposed to the Jeju 4·3 incident were identified according to the registration data of the Jeju 4·3 Victims' Organization. The victims were defined as those who died or disappeared, suffered from the aftereffects, became disabled, or were convicted of a crime due to the incident. A total of 158 surviving victims were eligible for the study, and 1,200 of 12,246 bereaved family members were extracted by a stratified random sampling method. Of the 1,358 eligible people, 161 refused to participate, 41 experienced difficulties during their interviews because of impaired hearing or vision (and were thus excluded), and 35 could not be reached after four attempts. Thus, 1,121 (82.5%) subjects (110 surviving victims and 1,011 of the victims' family members) were included in the present study. Interviewers, during in-person interviews, orally administered the various self-report questionnaires. Sociodemographic and health-related data were collected, including age, gender, duration of education, marital status, employment status, living arrangement, monthly household income, and chronic medical conditions.

To measure resilience, the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) was used. The CD-RISC-10 is a valid and reliable measure of the ability to cope with adversity, with higher scores reflecting greater resilience.

11 We employed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) for depression.

12 The CES-D comprises 20 items, and a score ≥ 21 indicated the presence of depressive symptoms according to a previous Korean validation study.

13 The PTSD Checklist-Civilian version (PCL-C) was used to measure subjects' PTSD symptoms.

14 The PCL-C is a 17-item self-reported questionnaire, and the cutoff score according to a previous Korean validation study is 50.

15 Psychosocial support was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS). This measures various aspects of perceived psychosocial support (emotional, informational, tangible, and affectionate support, as well as positive social interactions); a higher score indicates more psychosocial support.

16 To assess life satisfaction, the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used. The SWLS is a self-report measure of life satisfaction with five items; a higher score indicates greater life satisfaction.

17

The subjects were grouped into three categories according to their CD-RISC-10 score percentiles: high resilience (scores ≥ in the 75th percentile), medium (scores ≥ in the 25th percentile but < the 75th percentile), and low (scores < the 25th percentile), as in previous studies.

1819 We compared the three groups about the characteristics associated with different resilience levels. In the comparison of the three groups in terms of continuous and categorical variables, we used the Pearson χ

2 test, and analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc test, respectively. Next, variables that showed significant differences in univariate analysis were entered into multivariate logistic regression models. After appointing the high resilience group as the outcome group and the low resilience group as the reference group, we conducted the multivariate logistic regression to identify variables independently associated with higher resilience. In the first step (model 1), relevant factors were entered. In the second step (model 2), symptoms of depression and PTSD, psychosocial support status, and life satisfaction were entered after adjusting for demographic characteristics. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 25.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and

P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

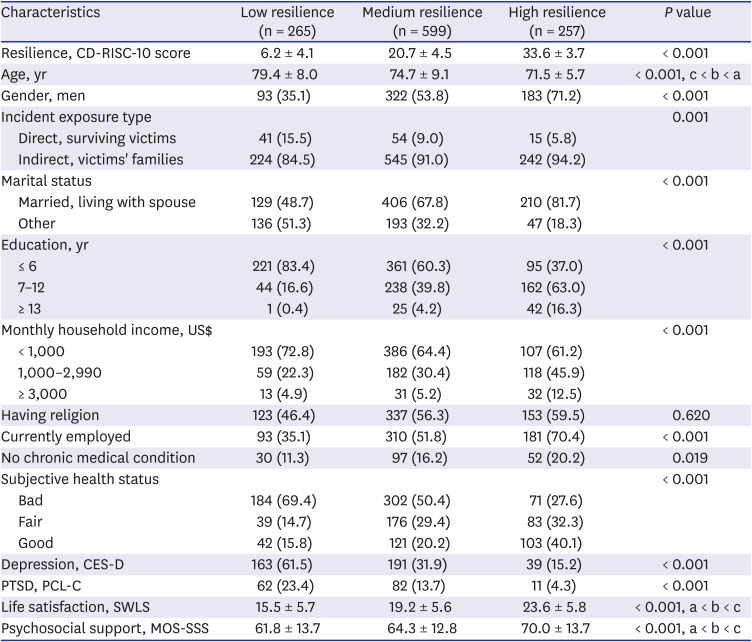

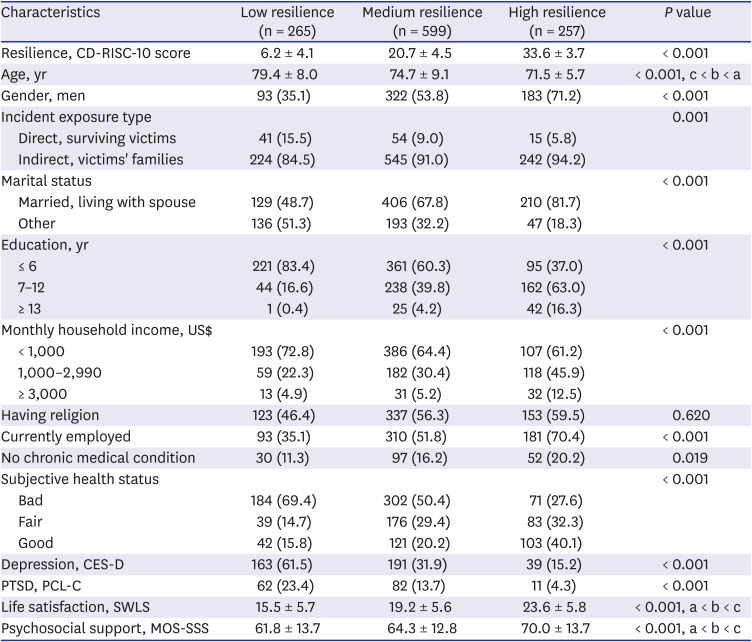

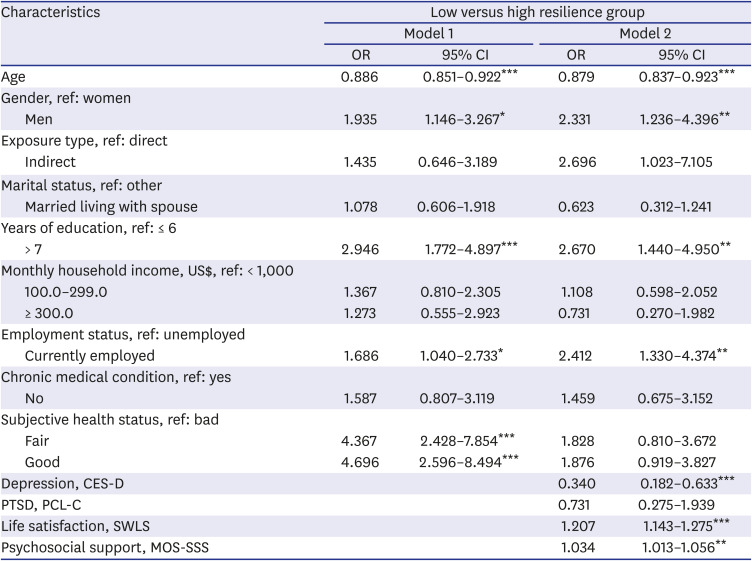

Of the 1,121 participants included in this analysis, 598 (53.3%) were men and 523 (46.7%) were women. The mean age of the participants was 75.1 years (standard deviation, 7.5 years). Of these participants, a total of 121 (10.8%) met the criteria for comorbid PTSD and depression, 34 (3.0%) had PTSD only, and 272 (24.3%) had depression only. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the low, medium, and high resilience groups are shown in

Table 1. The demographic characteristics that differed significantly among the three groups included mean age (

P < 0.001), gender (

P < 0.001), incident exposure type (

P = 0.001), marital status (

P < 0.001), education (

P < 0.001), employment (

P < 0.001), and monthly household income (

P < 0.001). We also found significant group differences in subjective health status (

P < 0.001) and chronic medical conditions (

P = 0.019). Resilience was negatively related to depression on the CES-D (

P < 0.001) and PTSD on the PCL-C (

P < 0.001). Significant group differences were seen for life satisfaction (

P < 0.001) and psychosocial support (

P < 0.001).

Table 1

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the low, medium, and high resilience groups

|

Characteristics |

Low resilience (n = 265) |

Medium resilience (n = 599) |

High resilience (n = 257) |

P value |

|

Resilience, CD-RISC-10 score |

6.2 ± 4.1 |

20.7 ± 4.5 |

33.6 ± 3.7 |

< 0.001 |

|

Age, yr |

79.4 ± 8.0 |

74.7 ± 9.1 |

71.5 ± 5.7 |

< 0.001, c < b < a |

|

Gender, men |

93 (35.1) |

322 (53.8) |

183 (71.2) |

< 0.001 |

|

Incident exposure type |

|

|

|

0.001 |

|

Direct, surviving victims |

41 (15.5) |

54 (9.0) |

15 (5.8) |

|

Indirect, victims' families |

224 (84.5) |

545 (91.0) |

242 (94.2) |

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Married, living with spouse |

129 (48.7) |

406 (67.8) |

210 (81.7) |

|

Other |

136 (51.3) |

193 (32.2) |

47 (18.3) |

|

Education, yr |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

≤ 6 |

221 (83.4) |

361 (60.3) |

95 (37.0) |

|

7–12 |

44 (16.6) |

238 (39.8) |

162 (63.0) |

|

≥ 13 |

1 (0.4) |

25 (4.2) |

42 (16.3) |

|

Monthly household income, US$ |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

< 1,000 |

193 (72.8) |

386 (64.4) |

107 (61.2) |

|

1,000–2,990 |

59 (22.3) |

182 (30.4) |

118 (45.9) |

|

≥ 3,000 |

13 (4.9) |

31 (5.2) |

32 (12.5) |

|

Having religion |

123 (46.4) |

337 (56.3) |

153 (59.5) |

0.620 |

|

Currently employed |

93 (35.1) |

310 (51.8) |

181 (70.4) |

< 0.001 |

|

No chronic medical condition |

30 (11.3) |

97 (16.2) |

52 (20.2) |

0.019 |

|

Subjective health status |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

Bad |

184 (69.4) |

302 (50.4) |

71 (27.6) |

|

Fair |

39 (14.7) |

176 (29.4) |

83 (32.3) |

|

Good |

42 (15.8) |

121 (20.2) |

103 (40.1) |

|

Depression, CES-D |

163 (61.5) |

191 (31.9) |

39 (15.2) |

< 0.001 |

|

PTSD, PCL-C |

62 (23.4) |

82 (13.7) |

11 (4.3) |

< 0.001 |

|

Life satisfaction, SWLS |

15.5 ± 5.7 |

19.2 ± 5.6 |

23.6 ± 5.8 |

< 0.001, a < b < c |

|

Psychosocial support, MOS-SSS |

61.8 ± 13.7 |

64.3 ± 12.8 |

70.0 ± 13.7 |

< 0.001, a < b < c |

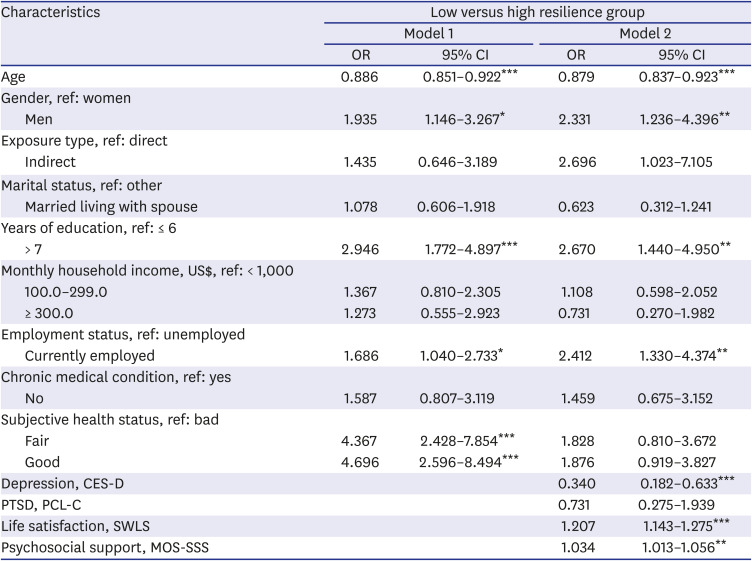

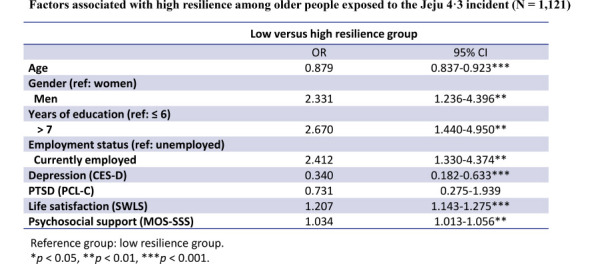

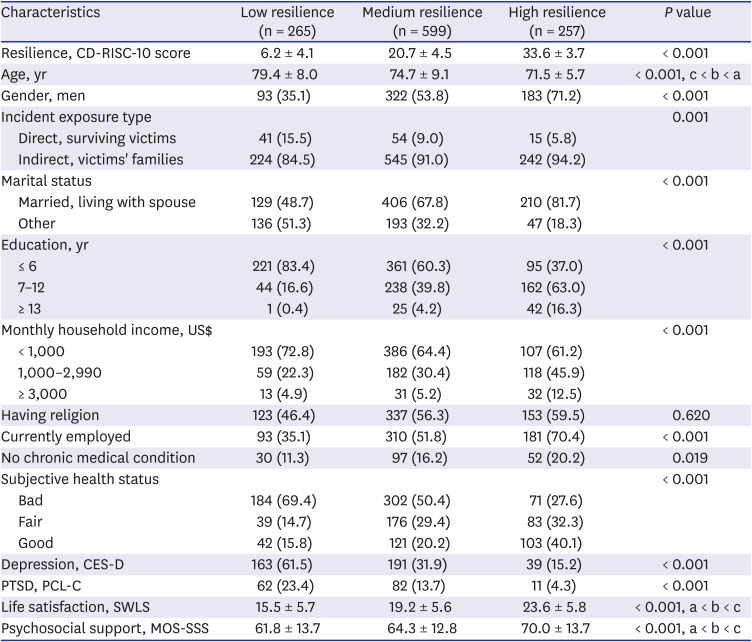

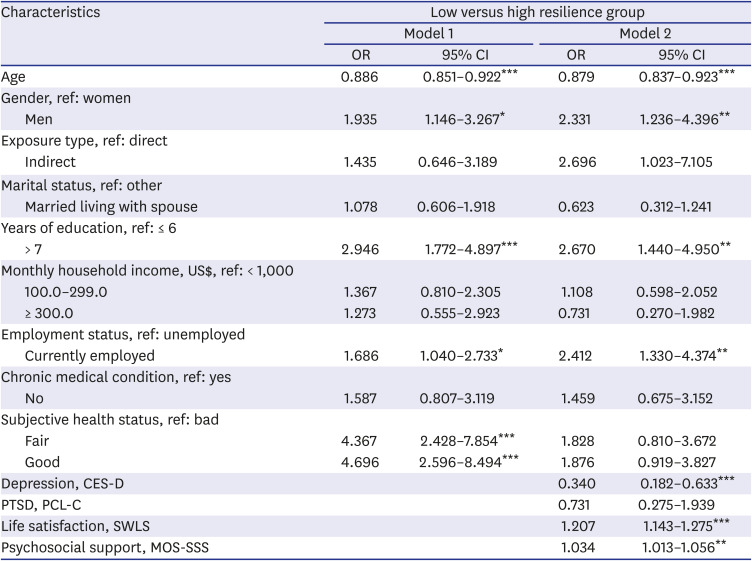

Table 2 summarizes the multivariate logistic regression analyses of factors associated with the high resilience group, using the low resilience group as the reference. Of the various demographic and clinical variables, younger age (

P < 0.001), being a man (

P = 0.014), higher education level (

P < 0.001), current employment (

P < 0.001), and fair or good subjective health status (both

P < 0.001) were significantly associated with high resilience (model 1). In the final model, which included all variables (model 2), the high resilience group were characterized by a low prevalence of depression (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.340; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.182–0.633,

P < 0.001) and high levels of life satisfaction (OR, 1.207; 95% CI, 1.143–1.275,

P < 0.001) and psychosocial support (OR, 1.207; 95% CI, 1.143–1.275,

P = 0.001). In addition, younger age (

P < 0.001), being a man (

P = 0.009), higher education level (

P = 0.002), and current employment (

P = 0.035) characterized the high-resilience group.

Table 2

Factors associated with resilience

|

Characteristics |

Low versus high resilience group |

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|

OR |

95% CI |

OR |

95% CI |

|

Age |

0.886 |

0.851–0.922***

|

0.879 |

0.837–0.923***

|

|

Gender, ref: women |

|

|

|

|

|

Men |

1.935 |

1.146–3.267*

|

2.331 |

1.236–4.396**

|

|

Exposure type, ref: direct |

|

|

|

|

|

Indirect |

1.435 |

0.646–3.189 |

2.696 |

1.023–7.105 |

|

Marital status, ref: other |

|

|

|

|

|

Married living with spouse |

1.078 |

0.606–1.918 |

0.623 |

0.312–1.241 |

|

Years of education, ref: ≤ 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

> 7 |

2.946 |

1.772–4.897***

|

2.670 |

1.440–4.950**

|

|

Monthly household income, US$, ref: < 1,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

100.0–299.0 |

1.367 |

0.810–2.305 |

1.108 |

0.598–2.052 |

|

≥ 300.0 |

1.273 |

0.555–2.923 |

0.731 |

0.270–1.982 |

|

Employment status, ref: unemployed |

|

|

|

|

|

Currently employed |

1.686 |

1.040–2.733*

|

2.412 |

1.330–4.374**

|

|

Chronic medical condition, ref: yes |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

1.587 |

0.807–3.119 |

1.459 |

0.675–3.152 |

|

Subjective health status, ref: bad |

|

|

|

|

|

Fair |

4.367 |

2.428–7.854***

|

1.828 |

0.810–3.672 |

|

Good |

4.696 |

2.596–8.494***

|

1.876 |

0.919–3.827 |

|

Depression, CES-D |

|

|

0.340 |

0.182–0.633***

|

|

PTSD, PCL-C |

|

|

0.731 |

0.275–1.939 |

|

Life satisfaction, SWLS |

|

|

1.207 |

1.143–1.275***

|

|

Psychosocial support, MOS-SSS |

|

|

1.034 |

1.013–1.056**

|

The characteristics of highly resilient individuals, and factors enhancing resilience, could inform the development of resilience-enhancing strategies. We observed that being a man, current employment, and a higher education level were associated with high resilience, similar to previous studies.

720 Our results confirmed the well-established gender difference in the rates of stress-related psychiatric conditions, including depression and PTSD.

21 In general, older Korean women have less access to education, and encounter more difficulties in achieving a high-level social position than men. Although a cross-sectional study cannot determine causality, it is reasonable to infer that the material and social resources associated with higher levels of education and employment reduce stress and increase resilience in men. As has been seen in previous work,

89 we found that high resilience was associated with a lower prevalence of depression and greater life satisfaction, consistent with previous studies. In the final model, after adjusting for all other factors, the absence of PTSD symptoms was less important to resilience than other factors. Finally, high levels of perceived psychosocial support were independently associated with high resilience among older people who had experienced early life trauma. Perceived psychosocial support, as distinct from actual support, improves resilience and predicts psychological well-being and a good quality of life in trauma-exposed people.

1022 In contrast, a lack of social support leads to maladaptive responses to stress, and is a major risk factor for the psychological sequelae associated with extreme stress in early life.

23

This cross-sectional study included a unique population of older individuals who survived the Jeju 4·3 incident. Enrolment of a larger sample would have allowed for a more in-depth exploration of the relationships among early life trauma, long-term psychological sequelae (such as depression) and resilience. Identifying factors associated with high resilience among older people exposed to early life trauma could facilitate the development of interventions enhancing resilience.

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jeju National University Hospital(IRB No. JEJUNUH 2015-09-002). All subjects received written and oral explanations regarding the study and provided written informed consent.

Go to :