INTRODUCTION

Late early childhood is a period when preschool children experience physical growth and emotional and cognitive development, and adequate nourishment and a balanced diet are critical during this stage. Preschool children also begin to form social relationships with others, which leads to development in their physical activities and capabilities. At this critical stage, children also develop their eating skills, form independent eating behaviors, and begin to have definite preferences towards food, thus forming their dietary habits. Since the dietary habits formed during this period not only affect the health, growth, and development of young children but could even affect the dietary habits and lifestyle-induced diseases as adults, it is pivotal for children to form healthy dietary habits at this stage [

1234].

The imbalance in the nutrition and food intake of preschool children in Korea, as well as their unbalanced diet, habits of skipping meals, and the increase in their fast-food intake, have become a social issue as such unhealthy dietary habits have led to health conditions, including overweight, obesity, and cavities [

567]. According to Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) VII-3 [

5], the nutrient intake of 3.8% of the children from the ages of 3 to 5 was deficient, whereas the nutrient intake of 2.0% of the children was excessive. That is, approximately 6% of the children within the age group were either under- or over-nourished, both of which are conditions that could affect the children's physical development. The report also showed that the percentage of the children who skipped breakfast increased from 6.9% in 2017 to 8.1% and that 34.5% of children between the ages of 3 to 5 dined out more than once every day. By skipping breakfasts, having irregular meals or eating behaviors, children are at risk of hindering their growth and development and forming unhealthy dietary habits at a young age [

67].

As eating behaviors affect the current nutrition and health of preschool children as well as the possibility of diseases, the eating behavior of preschool children should be analyzed through rigorous research and evaluation [

8]. Assessment tools for comprehensive and straightforward analyses of early childhood dietary habits have been developed and used to analyze various factors, such as the nutritional and dietary factors and demographical characteristics of the subjects [

291011121314].

In Korea, the nutrition quotient for preschoolers (NQ-P) has been developed for an assessment of the nutritional status and the quality of meals of preschool children [

2]. NQ-P is an assessment tool that provides a comprehensive outlook of the children's quality of meals and dietary habits. NQ-P targets the parents or caregivers of children between the ages of 3 to 5 and consists of 3 dimensions—balance, moderation, and environment—and 14 items. While some researchers have applied the nutrition quotient (NQ), which was created for elementary school students in their fifth or sixth grades, in assessment studies on dietary behaviors of preschool children, research on the dietary habits of preschool children that used NQ-P for assessment has been lacking; the small number of studies that used NQ-P were limited to the Daejeon, Jecheon, and Gwangju areas [

81516]. Studies that used NQ and NQ-P to assess the dietary behaviors of preschool children examined the difference by sex, region, weight, age, and body mass index (BMI) [

7815]. Research conducted on 5-year-old children living in Seoul showed that the NQ of obese children was lower than that of children with normal weight [

7] and that the NQ of breastfed children was significantly higher than that of bottle-fed children [

10].

A comparative study on the dietary behaviors of infants and preschool children in Ganghwa-gun showed that the NQ of infants was significantly higher than that of preschool children [

13]. The NQ scores of infants living in the Gyeongsan area proved to be at nutritional risk, all except the moderation dimension [

4]. In the case of preschool children living in Dongducheon, obese children had low scores in the balance among the NQ dimensions in terms of obesity [

14]. Among the studies that used NQ-P, one study on the dietary behaviors of preschool children in Jecheon showed that the total NQ-P score of the region was lower than the total national NQ-P score of 60.6. While there was no score difference by sex or age, a significant difference by age was found in the balance and moderation dimensions [

15]. The dietary behaviors score of preschool children in Daejeon was at a mid- to low-level at 58.5, and no significant difference by sex or age was found [

8]. In the case of Gwangju, the total NQ-P score was 59.9, and the score of children between the ages of 1 to 2 was higher than that of 3 to 5-year-old children [

16].

A thorough examination of the current dietary habits and the affecting factors is needed to instill healthy dietary habits in preschool children. The eating behaviors of preschool children are determined by individual and internal factors and environmental factors [

17], and studies have suggested that dietary behaviors, dietary attitudes, food intake, nutritional knowledge, educational level, feeding styles, and the socioeconomic level of the parents were also associated with the dietary habits of their children [

12141819202122232425262728293031]. It is likely that the food that the primary caregiver who plans the meals dislikes would be excluded from meals, and as children are less exposed to such food, they tend to form their dietary preferences and dietary habits with their primary caregivers as their mealtime role models. Research has proved that dietary behaviors, food choices, and the perception of nutrition facts differed by one's health consciousness [

3233343536]. To examine the affecting factors of the dietary behaviors of children, external characteristics such as parental dietary attitudes as well as their beliefs and level of thinking skills that form the basis of their behavior and their health consciousness should also be considered [

37].

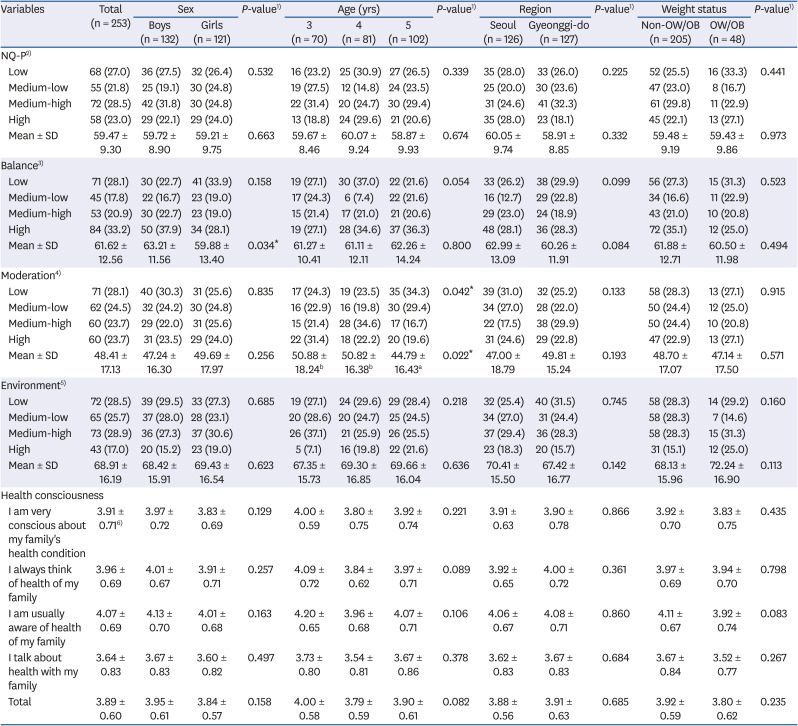

This study, therefore, used NQ-P and the data published at the time of the survey [

38] to analyze the quality of meals, dietary habits, and the food intake patterns of 3 to 5-year-old preschool children residing in Seoul (222,785 children, 16.29%) and Gyeonggi-do (384,861 children, 27.52%), which are the 2 top regions with the largest number of children within the age range. This study also examined whether NQ-P differed by sex, age, region, and weight status. In addition, this study analyzed the difference in the dietary scores of the children by their parents' health consciousness to provide meaningful basic data for the future development of policies and nutrition programs for improving the dietary behaviors of preschool children.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

The dietary environments of preschool children are rapidly changing in recent days, and health issues, including nutritional imbalance caused by fast-food and carbonated drinks, childhood obesity, and diabetes, are on the rise [

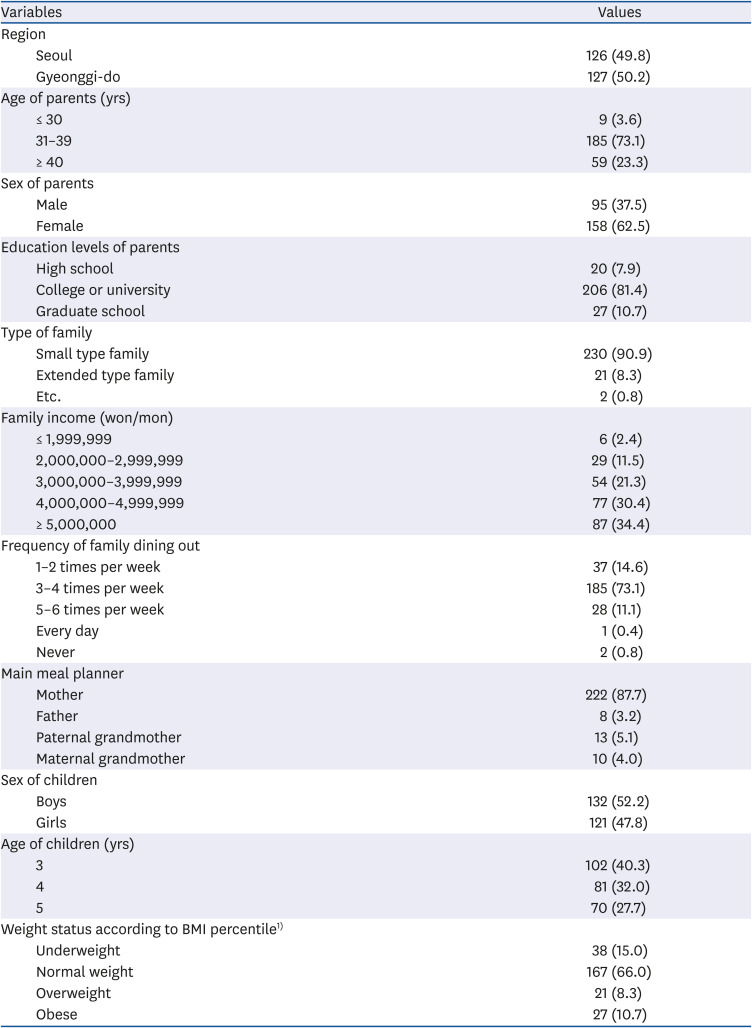

67]. This study thus used NQ-P to assess the dietary behaviors of preschool children living in Seoul and the Gyeonggi-do area. First, this study identified that 15.0% of the subjects were underweight, 10.7% obese, and that 8.3% were overweight. Considering that 3.8% of the children from the years 3 to 5 in KNHANES VII-3 [

5] were found to display signs of insufficient nutrient intake and that 2.0% had signs of excessive nutrient intake, this study found higher numbers of preschool children who were obese, overweight, or underweight.

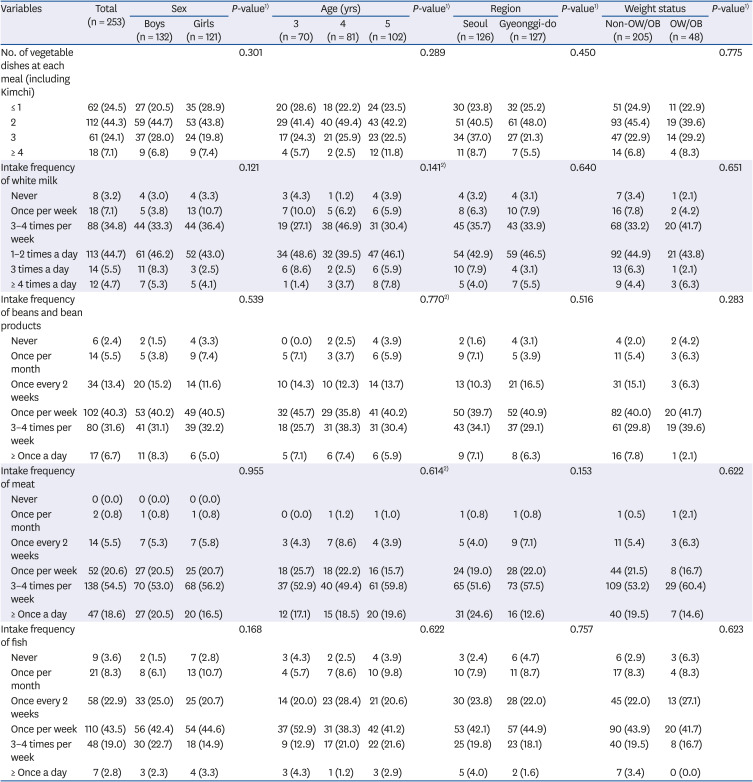

Analysis using NQ-P to compare the difference in dietary behaviors by sex, age, region, and weight status displayed no statistical significance in the balance dimension. The consumption of white milk, beans and bean products, meat, and fish is a key indicator to measure the intake of food and essential nutrients during childhood. In regards to the consumption of white milk, 54.9% of the children drank white milk at least once a day, while 45.1% did not drink white milk every day. Considering that 79.3% of the preschool children in the Gyeongsan area drank milk at least once a day [

4], the children in Seoul and the Gyeonggi-do area drank relatively less milk. The highest proportion of the respondents, at 40.3%, ate beans and bean products once a week, and the highest rate of eating meat was 3 to 4 times a week at 54.5%. No respondent replied that they did not eat meat. In the case of fish, the highest proportion of 43.5% responded that they ate fish once a week. This was similar to the intake patterns of tofu, meat, and fish found in preschool children from Daejeon [

8]. The dietary guideline for infants and preschool children, which is provided by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, recommends that children should consume many different types of food including grains, fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, and dairy, all of which suggest that the preschool children living in Seoul and the Gyeonggi-do area should be eating various kinds of food.

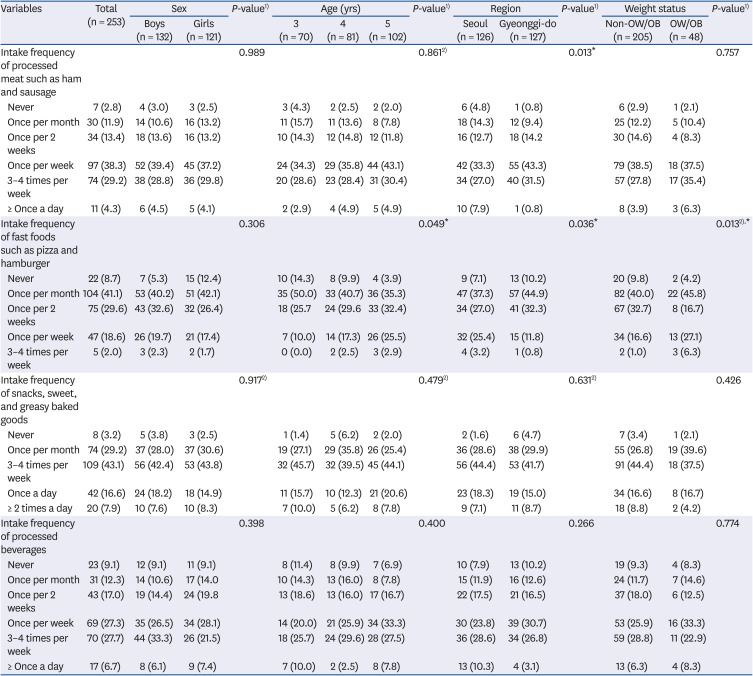

In the moderation dimension, this study found that the consumption frequency of processed meat and fast foods differed by region (

P < 0.05), and a significant difference was found in the consumption frequency of fast-food by age (

P < 0.05) and weight status (

P < 0.05). 68.2% in Seoul and 75.6% in Gyeonggi-do replied that they ate processed meat once or more times every week (

P < 0.05). The proportion of children who ate fast-food once or more times every week was 28.6% in Seoul and 12.6% in the Gyeonggi-do area, thereby showing a significant difference by region (

P < 0.05). In comparison with 11.9% in Daejeon [

8] and 4.4% in Dongducheon [

14], children in Seoul displayed a tendency to eat fast foods more frequently, which requires measures for improvement. A comparative study of fast foods consumption of students by region [

42] found that students living in big cities tend to consume fast foods the most. It is thus likely that the fast foods consumption patterns of preschool children would be similar, which, in Seoul, may have been affected by the lack of time to plan for meals at home. In regards to the consumption rate of fast foods was significantly higher in the 5-year-old children (

P < 0.05). Although it was not statistically significant, the same pattern was detected in the study on the preschool children in Daejeon [

8], as the 5 to 6-year-old children ate more fast foods than the 3 to 4-year-old children. The 3 to 5-year-old children in this study ate more fast foods than one to 2-year-old children, according to a study on preschool children in Gwangju [

16], all of which suggested that education on healthy diets are necessary as children tend to eat more processed foods as they grow. This study also found that the consumption frequency of fast foods of the obese group was significantly higher than that of the non-obese group (

P < 0.05), which would require guidance for the obese group to reduce their fast foods consumption and increase their consumption of healthy food, and to provide children with nutrition education to prevent obesity.

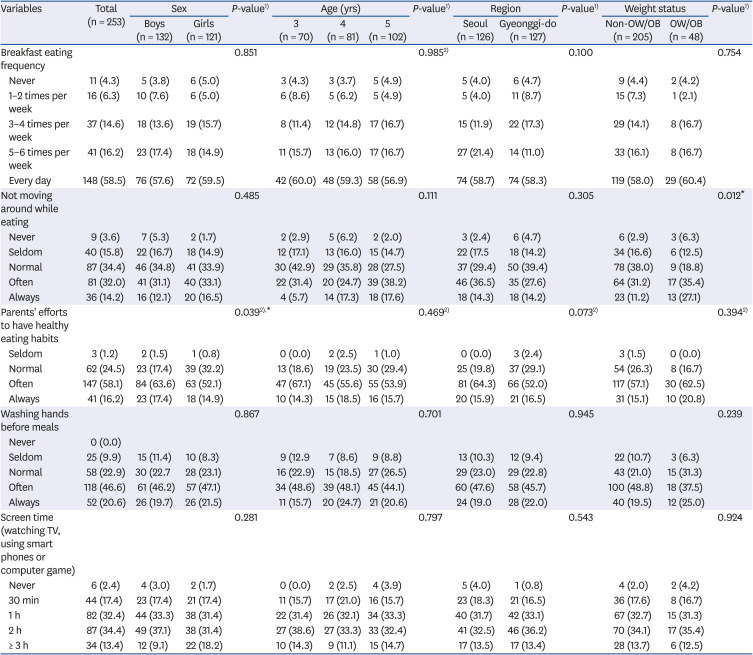

In the environment dimension, 74.7% of the respondents replied that they have breakfast 5 or more times every week, which was a lower rate compared to the survey results presented by KNHANES VII-3 [

5], which found that 82.8% of the chi, 19ldren from the age of 3 to 5 ate breakfast 5 or more times every week. Moreover, on the question whether their children do not wander around and eat their meals seated, the result was similar to the study conducted on the infants in Daejeon [

8] and showed that the frequency of non-overweight/obese group moving around during mealtime was significantly higher (

P < 0.05), which may be due to the cases in which underweight children wander during their meals. 16.2% responded that they have always put the effort in practicing a healthy diet, and there was also a significant difference in the practice of healthy diets by the sex of the children (

P < 0.05), which suggests that for children to be educated and instructed to maintain healthy diets at home, relevant educational contents for the parents should be developed. 20.6% of the respondents replied that they always had their children wash their hands before meals, which was markedly lower than that of the children from the Gyeongsan area (43.3%) [

4] and that of the children from Nowon-gu (39.9%) [

7]. This study further found that 47.8% of the subjects watched TV, smartphones, or computers for 2 hours or longer every day, which was higher than the rates in the Jecheon area, which was 35.3% [

15], and the Gyeongsan area, which was 23.8% [

4]. Repeated guidance on hand washing and limiting the use of electronic devices that are linked to the lessons at daycare centers and kindergarten should be provided at home.

An examination of the total NQ-P scores and the scores in each dimension sex, age, region, and weight status showed that the total NQ-P score of the subjects of this study was 59.47, which was considerably lower than the national-level score of 60.6 [

2], 59.6 of the Gyeongsan area [

4], 65.2 of the children in Dongducheon [

14], 62.1 of the children in Ganghwado [

13], and the score of 59.9 of the children living in Gwangju [

16], and only slightly higher than the score of children in Jecheon, which was 58.5. The overall average was also at the “mid-low” level, which would require further monitoring. 23.7% of preschool children were classified as the high level, the proportion of which was relatively lower than other regions, including Daejeon, which was at 30% [

8], and the Jecheon area, which was at 24.7% [

15]. The findings of this study suggested that education for preschool children in the Seoul and Gyeonggi-do region and their parents is pivotal to improve the dietary habits of the children and the quality of their meals.

The subjects of this study were classified as “mid-low” in all dimensions as they scored 61.62 in the balance dimension, 48.41 in the moderation dimension, and 68.91 in the environment dimension. This study compared the results with previous studies conducted on the national level and in Jecheon, Daejeon, and Gwangju that used NQ-P. The scores in the national survey [

2] were 60.49 for balance, 51.49 for moderation, and 71.66 for environment; the scores of the subjects in Jecheon [

15] were, 60.5 for balance, 51.26 for moderation, and 63.78 for environment; the scores of the subjects in Daejeon [

8] were 60.5 for balance, 50.2 for moderation, and 65 for environment; and the scores of the subjects in Gwangju [

16] were 61.1 for balance, 56.0 for moderation, and 62.6 for environment. The score of the balance and environment dimension of this study was relatively higher than the results in the other regions. However, the score of moderation was relatively lower, which suggests that the preschool children in Seoul and the Gyeonggi-do area should receive education for improving their dietary behaviors.

The average scores of the NQ-P showed that there was a significant difference by sex in the balance dimension and a significant difference by age in the moderation dimension. The scores in the moderation dimension tended to drop significantly as the children became older while the scores in the balance and environment dimensions increased by age. This result showed that while children are exposed to more diverse food and gain better eating attitudes as they grow, they come to have more encounters with unhealthy food at the same time. Such results were also found in the research on the children in Daejeon [

8] and in Gwangju [

16] where the consumption frequency of processed food and the consumption of fast foods increased by age, all of which shows how dietary education on the consumption of processed food and fast foods for preschool children should be programmed to fit the dietary characteristics by each age group for the children to form healthy dietary habits.

Since the moderation dimension could be determined by the parents’ attitudes towards food purchase and their preference toward foods such as processed meat and fast foods, education on choosing and feeding healthy food for children for parents would be necessary. This study also found a difference between the overweight/obese group and the non-overweight/non-obese group in the “environment” dimension. Although there was no significant difference in the 2 group's average scores, the score of the obese group was higher. Considering the facts that there were underweight children included in the non-obese and non-overweight group and that 15% of the subjects were underweight, and also that 15.2% of the children in the national level study [

2] displayed signs of picky eating, the underweight children seem to have lower BMI as they tend to be picky eaters who do not focus during mealtime and eat smaller portions than required. A study on the dietary attitudes of children in Daegu in regards to obesity [

43] also showed that the underweight group's score of the item, “My child does not wander during mealtime,” was significantly low (

P < 0.05). This study further pointed out the dietary issues of underweight children by finding that the more underweight the child was, there was a more significant drop in the average of the score on dietary behaviors (

P < 0.001). Mealtime guidance and education programs for improving eating environments should be provided so that the children, who are at a critical stage for their growth, do not suffer from an imbalance in their nutrition and undernutrition caused by a loss of appetite, picky eating habits, and hostile eating environments.

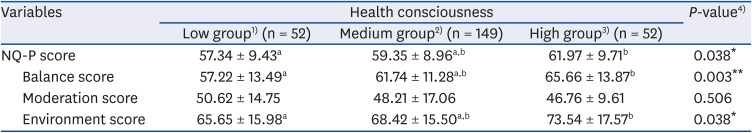

The average score of the parents' health consciousness in this study was 3.89, and there was no difference according to the characteristics of the subjects. An examination of the NQ-P scores concerning the health consciousness of the subjects showed that the group with higher health consciousness had significantly higher total NQ-P scores (61.97,

P < 0.05) and in the balance (65.66,

P < 0.01) and environment (73.54,

P < 0.05) dimensions. A study conducted on college students in Busan found that the rate of health practices was significantly higher in students who were more health-conscious [

32]. Another study presented that the intention to use nutritional facts was higher among highly self-conscious consumer groups [

36], which suggests that the highly health-conscious parents would likely choose healthy food and practice healthy behavior and would have a positive effect on their child's healthy diet. Taken together, there is a need for educational programs that could improve the parents' health-consciousness for children to have and continue to have healthy eating habits. Regarding the balance and environment dimensions, the group of parents with low health-consciousness should be encouraged to get interested in themes such as having a balanced meal or establishing healthy eating habits. It would be more effective to provide the high health-consciousness group with more in-depth nutrition education. No significant difference was found according to the parents’ health-consciousness in the moderation dimension. Considering that the total average in the moderation dimension was lower than that from a study on other areas, there is an urgent need for education programs for preschool children who experience a variety of food to eat less processed meat, processed beverages, and fast foods.

In conclusion, the total score of the dietary behaviors of preschool children in Seoul and the Gyeonggi-do was low compared to the national-level survey and was placed at the mid-low level, thus requiring constant monitoring. This study also found a significant difference in the score of the eating behavior of preschool children depending on the parents' health consciousness. While previous studies on the factors that affect the eating behaviors of preschool children focused on the demographic factors, this study newly presented that the parents' beliefs that underlie their actions, that is, their health consciousness could also be one of the factors. This study identified distinctive dietary attitudes of the subjects that were not found in the previous studies conducted in other regions. The findings of this study also implied that the dietary habits and the quality of meals of preschool children could be at risk, which would require in-depth research not only on the diet of obese children but also on the diet of underweight children. As this study was regionally limited to Seoul and the Gyeonggi-do area, it would be difficult to generalize the findings. There was also the possibility that the parents may have underestimated or overestimated their children's eating habits in responding to the questionnaire. Since the degree of obesity was measured based on the safe-contained values entered by the parents or the caregivers, the possibility of misclassification cannot be excluded. Therefore, prospective studies are needed, and we suggest that future research that uses NQ-P to consecutively assess the dietary behaviors of preschool children on the national level would be able to provide the changes in the dietary behaviors of preschool children and serve as meaningful data for future policies on improving nutrition and health.

It would also be helpful for children to form healthy habits and positive nutritional status by examining the various factors related to the dietary behavior and growth of children and parents in the future. As well, further research on the variables of the parents' beliefs of eating behavior and healthy behavior and their effects on preschool children would be useful in developing effective educational programs on healthy dietary habits.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download