2. Oh HS. Important significant factors of health-related quality of life(EQ-5D) by age group in Korea based on KNHANES (2014). J Korean Data Inf Sci Soc. 2017; 28:573–584.

3. Han KS. Stress of the mid-life stage. Korean J Stress Res. 2007; 15:263–270.

4. Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007; 23:887–894. PMID:

17869482.

5. Park HE, Bae Y. Eating habits in accordance with the mental health status: the 5th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2010–2012. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc. 2016; 17:168–181.

6. Choi HJ, Kim BJ, Kim IJ. Prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbance in community dwelling adults in Korea. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2013; 25:183–193.

7. Shim HY, Kwon OJ, Kim MJ, Song EJ, Moon SY, Nam YD, Nam DH, Lee JH, Koo BS, Kim HJ. A comparative study on the quality of sleep, tongue diagnosis, and oral microbiome in accordance to the Korean medicine pattern differentiation of insomnia. J Korean Med Obes Res. 2020; 20:40–51.

9. Doo M, Kim Y. Sleep duration and dietary macronutrient consumption can modify the cardiovascular disease for Korean women but not for men. Lipids Health Dis. 2016; 15:17. PMID:

26819201.

10. Kim CE, Shin S, Lee HW, Lim J, Lee JK, Shin A, Kang D. Association between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18:720. PMID:

29895272.

11. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Sydney: Health Communications Australia;2000.

12. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983; 24:385–396. PMID:

6668417.

13. Lee J, Shin C, Ko YH, Lim J, Joe SH, Kim S, Jung IK, Han C. The reliability and validity studies of the Korean version of the perceived stress scale. Korean J Psychosom Med. 2012; 20:127–134.

14. Garaulet M, Canteras M, Morales E, López-Guimera G, Sánchez-Carracedo D, Corbalán-Tutau MD. Validation of a questionnaire on emotional eating for use in cases of obesity: the emotional eater questionnaire (EEQ). Nutr Hosp. 2012; 27:645–651. PMID:

22732995.

15. Saleh-Ghadimi S, Dehghan P, Abbasalizad Farhangi M, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Jafari-Vayghan H. Could emotional eating act as a mediator between sleep quality and food intake in female students? Biopsychosoc Med. 2019; 13:15. PMID:

31236132.

16. Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001; 2:297–307. PMID:

11438246.

17. Cho YW, Song ML, Morin CM. Validation of a Korean version of the insomnia severity index. J Clin Neurol. 2014; 10:210–215. PMID:

25045373.

18. Jo HM. The association between sleep quality and perceived stress among students from 2 universities [master's thesis]. Seoul: Ewha Womans University;2015.

19. Park SY, Joe SH, Kim SH, Han CS, Ham BJ, Ko YH. Fatigue and its association with socio-demographic and clinical variables in a working population. Korean J Psychosom Med. 2014; 22:3–12.

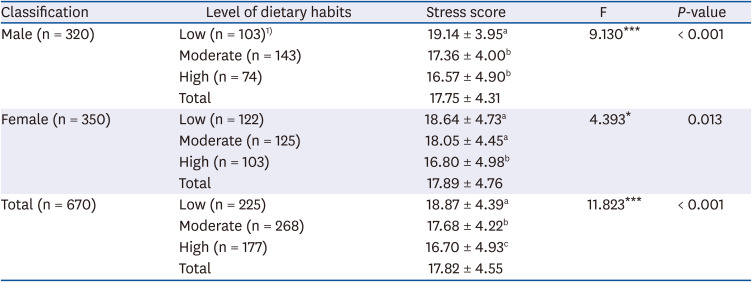

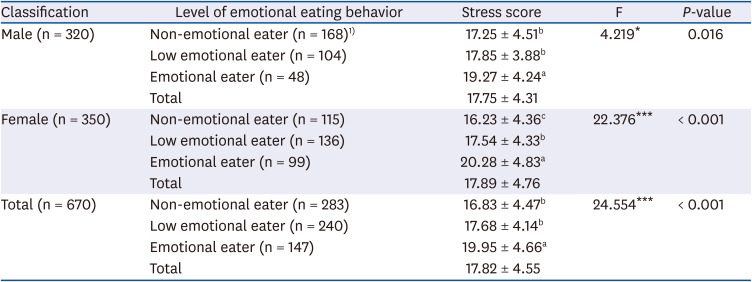

20. Kim HK, Kim JH. Relationship between stress and eating habits of adults in Ulsan. Korean J Nutr. 2009; 42:536–546.

21. Seo EY, Lee SL. Factors influencing dietary behaviors and stress in male and female college students. J Korean Soc Sch Health. 2018; 31:186–195.

22. Seo YJ, Kim MH, Kim MH, Choi MK. Status and relationships among lifestyle, food habits, and stress scores of adults in Chungnam. Korean J Community Nutr. 2012; 17:579–588.

23. Yoon HS. An assessment on the dietary attitudes, stress level and nutrient intakes by food record of food and nutrition major female university students. Korean J Nutr. 2006; 39:145–159.

24. Park JE, Kim SJ, Choue RW. Study on stress, depression, binge eating, and food behavior of high school girls based on their BMI. Korean J Community Nutr. 2009; 14:175–181.

25. Lee SJ, Kim YR, Seo SH, Cho MS. A study on dietary habits and food intakes in adults aged 50 or older according to depression status. J Nutr Health. 2014; 47:67–76.

26. Lee YJ. Gender differences in factors associated with the severity of depression in middle-aged adults: an analysis of 2014 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Korea Converg Soc. 2018; 9:549–559.

27. Watson NF, Harden KP, Buchwald D, Vitiello MV, Pack AI, Strachan E, Goldberg J. Sleep duration and depressive symptoms: a gene-environment interaction. Sleep. 2014; 37:351–358. PMID:

24497663.

28. Lee MA, Lee EJ, Soh HK, Choi BS. Analysis on stress and dietary attitudes of male employees. Korean J Community Nutr. 2011; 16:337–352.

29. Sung MJ, Chang KJ. Correlations among life stress, sleep, anthropometric measurement and nutrient intakes of college students. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2007; 36:840–848.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download