|

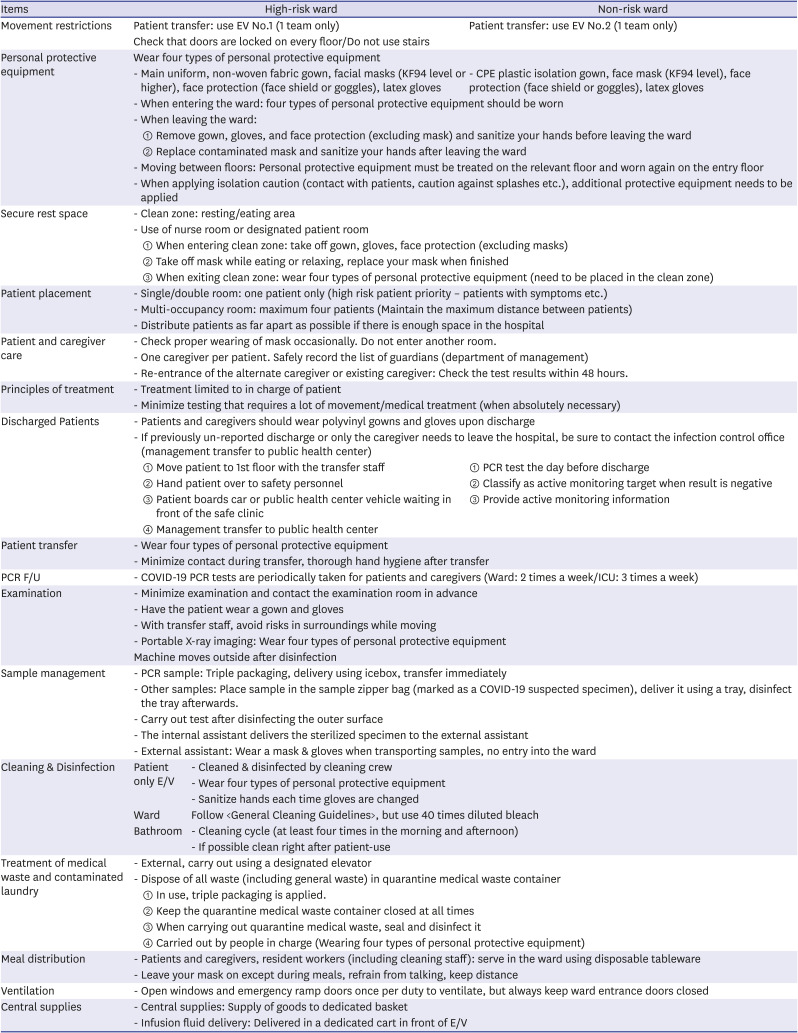

Movement restrictions |

Patient transfer: use EV No.1 (1 team only) |

Patient transfer: use EV No.2 (1 team only) |

|

Check that doors are locked on every floor/Do not use stairs |

|

Personal protective equipment |

Wear four types of personal protective equipment |

|

- Main uniform, non-woven fabric gown, facial masks (KF94 level or higher), face protection (face shield or goggles), latex gloves |

- CPE plastic isolation gown, face mask (KF94 level), face protection (face shield or goggles), latex gloves |

|

- When entering the ward: four types of personal protective equipment should be worn |

|

- When leaving the ward: |

|

① Remove gown, gloves, and face protection (excluding mask) and sanitize your hands before leaving the ward |

|

② Replace contaminated mask and sanitize your hands after leaving the ward |

|

- Moving between floors: Personal protective equipment must be treated on the relevant floor and worn again on the entry floor |

|

- When applying isolation caution (contact with patients, caution against splashes etc.), additional protective equipment needs to be applied |

|

Secure rest space |

- Clean zone: resting/eating area |

|

- Use of nurse room or designated patient room |

|

① When entering clean zone: take off gown, gloves, face protection (excluding masks) |

|

② Take off mask while eating or relaxing, replace your mask when finished |

|

③ When exiting clean zone: wear four types of personal protective equipment (need to be placed in the clean zone) |

|

Patient placement |

- Single/double room: one patient only (high risk patient priority – patients with symptoms etc.) |

|

- Multi-occupancy room: maximum four patients (Maintain the maximum distance between patients) |

|

- Distribute patients as far apart as possible if there is enough space in the hospital |

|

Patient and caregiver care |

- Check proper wearing of mask occasionally. Do not enter another room. |

|

- One caregiver per patient. Safely record the list of guardians (department of management) |

|

- Re-entrance of the alternate caregiver or existing caregiver: Check the test results within 48 hours. |

|

Principles of treatment |

- Treatment limited to in charge of patient |

|

- Minimize testing that requires a lot of movement/medical treatment (when absolutely necessary) |

|

Discharged Patients |

- Patients and caregivers should wear polyvinyl gowns and gloves upon discharge |

|

- If previously un-reported discharge or only the caregiver needs to leave the hospital, be sure to contact the infection control office (management transfer to public health center) |

|

① Move patient to 1st floor with the transfer staff |

① PCR test the day before discharge |

|

② Hand patient over to safety personnel |

② Classify as active monitoring target when result is negative |

|

③ Patient boards car or public health center vehicle waiting in front of the safe clinic |

③ Provide active monitoring information |

|

④ Management transfer to public health center |

|

|

Patient transfer |

- Wear four types of personal protective equipment |

|

- Minimize contact during transfer, thorough hand hygiene after transfer |

|

PCR F/U |

- COVID-19 PCR tests are periodically taken for patients and caregivers (Ward: 2 times a week/ICU: 3 times a week) |

|

Examination |

- Minimize examination and contact the examination room in advance |

|

- Have the patient wear a gown and gloves |

|

- With transfer staff, avoid risks in surroundings while moving |

|

- Portable X-ray imaging: Wear four types of personal protective equipment |

|

Machine moves outside after disinfection |

|

Sample management |

- PCR sample: Triple packaging, delivery using icebox, transfer immediately |

|

- Other samples: Place sample in the sample zipper bag (marked as a COVID-19 suspected specimen), deliver it using a tray, disinfect the tray afterwards. |

|

- Carry out test after disinfecting the outer surface |

|

- The internal assistant delivers the sterilized specimen to the external assistant |

|

- External assistant: Wear a mask & gloves when transporting samples, no entry into the ward |

|

Cleaning & Disinfection |

Patient only E/V |

- Cleaned & disinfected by cleaning crew |

|

- Wear four types of personal protective equipment |

|

- Sanitize hands each time gloves are changed |

|

Ward |

Follow <General Cleaning Guidelines>, but use 40 times diluted bleach |

|

Bathroom |

- Cleaning cycle (at least four times in the morning and afternoon) |

|

- If possible clean right after patient-use |

|

Treatment of medical waste and contaminated laundry |

- External, carry out using a designated elevator |

|

- Dispose of all waste (including general waste) in quarantine medical waste container |

|

① In use, triple packaging is applied. |

|

② Keep the quarantine medical waste container closed at all times |

|

③ When carrying out quarantine medical waste, seal and disinfect it |

|

④ Carried out by people in charge (Wearing four types of personal protective equipment) |

|

Meal distribution |

- Patients and caregivers, resident workers (including cleaning staff): serve in the ward using disposable tableware |

|

- Leave your mask on except during meals, refrain from talking, keep distance |

|

Ventilation |

- Open windows and emergency ramp doors once per duty to ventilate, but always keep ward entrance doors closed |

|

Central supplies |

- Central supplies: Supply of goods to dedicated basket |

|

- Infusion fluid delivery: Delivered in a dedicated cart in front of E/V |

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download