1. GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018; 392:1736–1788. PMID:

30496103.

3. Statistics Korea. Causes of Death Statistics in 2019. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2020.

4. Mensah GA, Wei GS, Sorlie PD, et al. Decline in cardiovascular mortality: possible causes and implications. Circ Res. 2017; 120:366–380. PMID:

28104770.

5. Lee SW, Kim HC, Lee HS, Suh I. Thirty-year trends in mortality from cardiovascular diseases in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2015; 45:202–209. PMID:

26023308.

6. Lee SW, Kim HC, Lee HS, Suh I. Thirty-year trends in mortality from cerebrovascular diseases in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2016; 46:507–514. PMID:

27482259.

7. Sung KC, Ryu S, Cheong ES, et al. All-cause and cardiovascular mortality among Koreans: effects of obesity and metabolic health. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 49:62–71. PMID:

26094228.

8. Hong JS, Kang HC, Lee SH, Kim J. Long-term trend in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction in Korea: 1997-2007. Korean Circ J. 2009; 39:467–476. PMID:

19997542.

9. Kim RB, Kim HS, Kang DR, et al. The trend in incidence and case-fatality of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction patients in Korea, 2007 to 2016. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34:e322. PMID:

31880418.

10. Seo SR, Kim SY, Lee SY, et al. The incidence of stroke by socioeconomic status, age, sex, and stroke subtype: a nationwide study in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2014; 47:104–112. PMID:

24744827.

11. Kim JY, Kang K, Kang J, et al. Executive summary of stroke statistics in Korea 2018: a report from the epidemiology research council of the Korean Stroke Society. J Stroke. 2019; 21:42–59. PMID:

30558400.

12. Lee JH, Lim NK, Cho MC, Park HY. Epidemiology of heart failure in Korea: present and future. Korean Circ J. 2016; 46:658–664. PMID:

27721857.

13. Youn JC, Han S, Ryu KH. Temporal trends of hospitalized patients with heart failure in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:16–24. PMID:

28154584.

14. Kim HC, Cho SMJ, Lee H, et al. Korea hypertension fact sheet 2020: analysis of nationwide population-based data. Clin Hypertens. 2021; 27:8. PMID:

33715619.

15. Kim BY, Won JC, Lee JH, et al. Diabetes fact sheets in Korea, 2018: an appraisal of current status. Diabetes Metab J. 2019; 43:487–494. PMID:

31339012.

17. Nam GE, Kim YH, Han K, et al. Obesity fact sheet in Korea, 2018: data focusing on waist circumference and obesity-related comorbidities. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019; 28:236–245. PMID:

31909366.

18. Huh JH, Kang DR, Jang JY, et al. Metabolic syndrome epidemic among Korean adults: Korean survey of cardiometabolic syndrome (2018). Atherosclerosis. 2018; 277:47–52. PMID:

30172084.

19. Seong SC, Kim YY, Khang YH, et al. Data resource profile: The National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46:799–800. PMID:

27794523.

20. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43:69–77. PMID:

24585853.

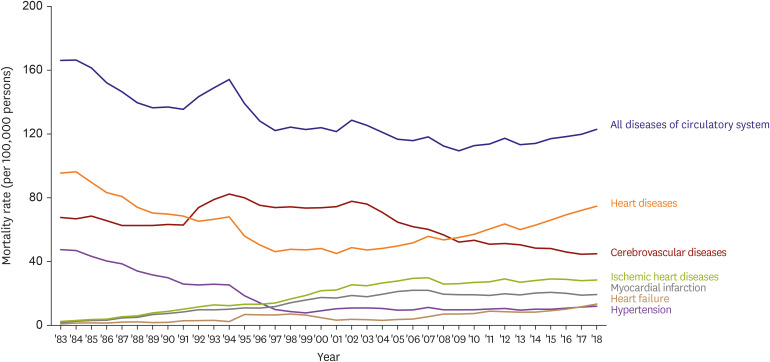

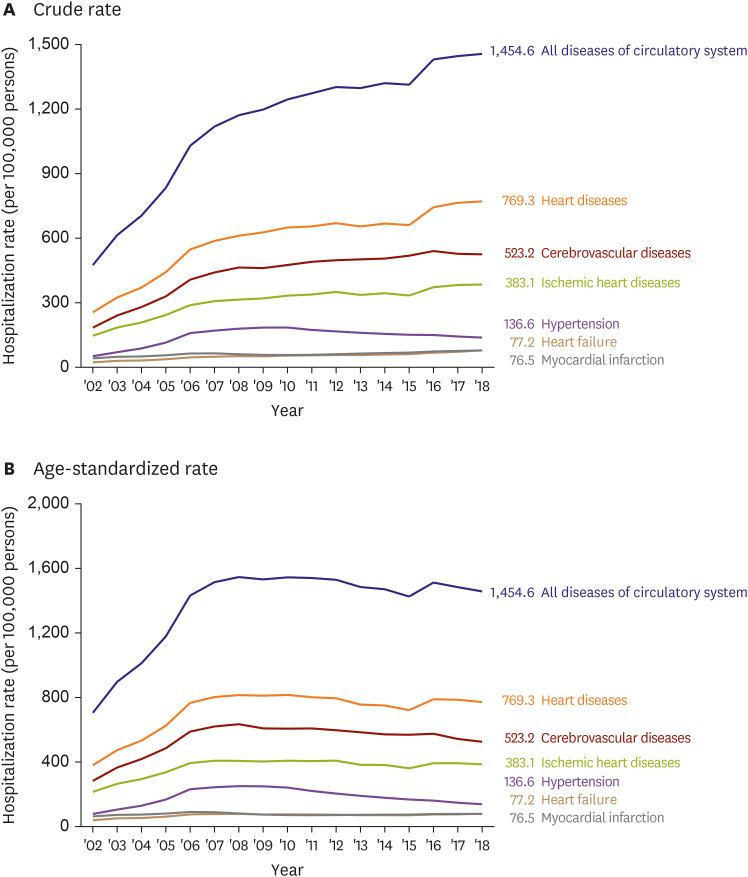

21. Baek J, Lee H, Lee HH, Heo JE, Cho SM, Kim HC. Thirty-six year trends in mortality from diseases of circulatory system in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2021; 51:320–332. PMID:

33821581.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download