Abstract

Scholarly journals are hubs of hypotheses, evidence-based data, and practice recommendations that shape health research and practice worldwide. The advancement of science and information technologies has made online accessibility a basic requirement, paving the way for the advent of open access publishing, and more recently, to web-based health journalism. Especially in the time of the current pandemic, health professionals have turned to the internet, and primarily to social media, as a source of rapid information transfer and international communication. Hence, the current pandemic has ushered an era of digital transformation of science, and we attempt to understand and assess the impact of this digitization on modern health journalism.

Go to :

Scholarly journals are hubs of hypotheses, evidence-based data, and practice recommendations that shape health research and practice worldwide. For centuries, such journals have served professional societies striving to solve closely related societal and healthcare issues. Some of the most successful and influential journals have emerged as the essential platforms for aggregating and publicizing scientific breakthroughs. One such example is Nature with its exclusive role for the global scientific community and individual researchers generating and testing unique hypotheses.

The advancement of science and information technologies has made online accessibility a basic requirement for comprehensively covering large volumes of scientific literature and synthesizing new evidence influencing global health. Keeping this in mind, the Budapest Open Access Initiative first coined the term “Open Access” back in 2001 and paved the way for publicly disseminating and archiving scholarly works which may improve education, research, and practice all over the world.12 To meet the growing demands of open search engines, platforms, and databases, the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) was launched in 2003 to register open-access journals across all academic disciplines and in all languages.23 Over the past years, the number of DOAJ listed periodicals has increased from initial 300 to more than 16,000, representing 125 countries.

Open access publishing, with its diverse quality characteristics, access options, and business models, has offered enormous opportunities for all researchers and authors who aimed to publicize their works and receive the global readership response. The global initiative has been embraced by all stakeholders of science communication.4 As a result, an atmosphere of uninterrupted education and research has been created to offer equal opportunities to all able scholars and disseminate their knowledge via online platforms, networking sites, and various social media channels.5 The new academic world has opened and exposed its once securely guarded resources to public views, criticism, and (re)use. With unprecedented growth of social media in the past decade, these platforms and related aggregating services have become inseparable parts of most advanced journals and bibliographic databases such as Scopus. The integration of traditional and alternative open-access media has broadened the global viewership (readership) and, at the same time, necessitated a selective approach to what is posted and disseminated online.6

In the time of the current pandemic, health professionals have turned to the Internet, and primarily to social media, as a source of rapid information transfer and a reflection of the dynamic changes in the global health.78 Furthermore, in light of the current situation, several journals have ceased to release printed versions of their issues and have completely adopted the web-based approach, marking the end of the paper-based era, and heralding the onset of the modern digital era of health journalism.

Social media have come to the fore as reliable platforms for online research, emergency meetings, and networking sites for aggregating various audio and video materials and gauging specialist and general public views on the ongoing pandemic.910

Social media see millions of active users accrue on a regular basis, with Twitter currently having approximately 350 million users.11 An example of how the medical community has turned to social media for the spread of knowledge and communication is the international paediatric critical care community, which studied the use of the Twitter-generated 2016 hashtag #PedsICU in the COVID-19 pandemic.12 The study demonstrated a rise in the use of this hashtag along with coronavirus-related hashtags, the most popular of which were links to open-access resources.12

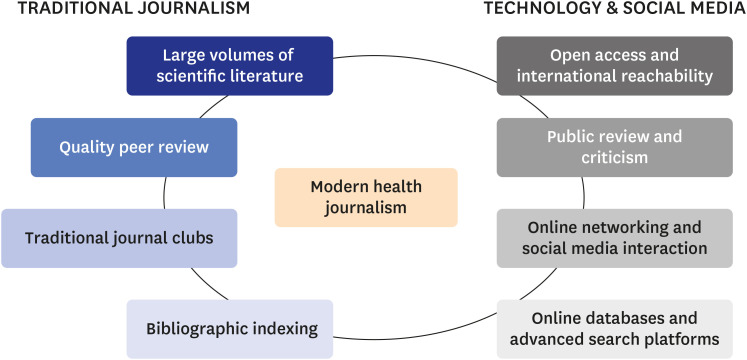

The integration of social media with scholarly journals increases viewership and readership, immediately reflecting on published contents and contributing to science mapping metrics such as altmetrics13 (Fig. 1). The transit of journal clubs to social media such as Twitter further increases the implications of scholarly articles for education. The online interaction of students with their mentors enables uninterrupted education and quest for knowledge in the time of crisis and travel restrictions.14 Social media is increasingly used to conduct survey studies and generate emergency data that immediately influence public health strategies. Numerous online survey reports are now published with support of global social media users, sharing their views on old and emerging diseases and reflecting on health infrastructure.15

The main drawback of information dissemination through social media that may negatively impact online users' health is the lack of peer review and professional filtering options. Such a drawback became apparent during the initial stage of the pandemic when unchecked information on COVID-19 therapies received a huge social media attention and misinterpreted by the public as globally endorsed.1617 This has become increasingly apparent in the current pandemic situation, where misinformation regarding the ill effects of the vaccines have gained enormous support on several social media platforms, providing momentum to the anti-vaccine movement, and hindering the efforts of the national administrations to carry out a successful vaccination drive. Additionally, a recent survey demonstrated that nearly 62% of scholars rely on social media for retrieving information on COVID-19 which may be erroneous and dangerous for patient lives.17 Authors sometimes upload their non-reviewed and preliminary data on social media, leading to sparks with severe repercussions for the scientific community.17 As such, experts in social media (digital editors) should be able to verify the credibility of sources prior to post-publication promotion.

An important aspect of scholarly publishing is quality peer review by experts who can evaluate logical flow, methodological rigour, evidence, and ethical grounds of research and reviews. The reviewers' primary responsibility is to provide an objective evaluation, helping editors to select and publish flawless articles. It appeared, however, that the peer review itself is deficient due to several loopholes allowing substandard, unethical, and fraudulent articles find their way to the global readership. Several solutions have been proposed to choose the best reviewers, create their registry, and increase the transparency of the review.18 The widely promoted Open Researcher and Contributor IDs (ORCID) and Publons reviewer profiles have become instrumental for increasing visibility of the best reviewers and likelihood of their repetitive engagement in quality evaluations.19 The Publons platform itself is integrated with Altmetrics.com; and such an integration further increases visibility of the reviewer evaluations.

Another critical aspect of modern health journalism is visibility of scholarly articles on reliable bibliographic databases and advanced search platforms to allow researchers retrieving validated local and international documents.20 The Scopus database and the Open Ukrainian Citation Index (OUCI; https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/) are perhaps the best examples of how Open Access, digitization, and social media have jointly transformed post-publication promotion and scholarly reuse of scientific information. Scopus and OUCI publicly display Plum Analytics social media reports (Plum Prints) next to traditional citations to allow comprehensive evaluation of covered documents.

In times of massive (mis)information flow, personalised feeds and sets of recommended items selected by digital tools and platforms may help further common academic and learning interests.21 Powerful automated algorithms of social media may automatically select and offer relevant information to individual users such as busy clinicians and health journalists. This approach, however, creates a room for bias when dealing with controversial matters. Users may be served specific content tailored to their scientific beliefs or right-winged versus left-winged online persona, bringing in potential for confirmation bias.2223

In the past few years, scientific research, and health journalism have been greatly influenced by numerous ethical issues. The ethics committee of every organisation addresses these issues; the primary responsibility of these ethical guidelines is to ensure the safety of all beings' dignity, human and otherwise, incorporated in these projects. However, it is nearly impossible to apprehend every possible scenario that may present, and hence these guidelines are undergoing constant modification to adapt to the evolving science.

The current pandemic has ushered an era of digital transformation of science, which has provided an important platform not only for rapid exchange of information and international scientific communication, but also for a more focused and streamlined approach to indexing, accessing, and referencing the large volume of scientific literature that has presented itself in the past years. The integration of social media as a digital means of health journalism has further broadened the readership of these scholarly journals and opened doors to public review. However, if left unchecked, these online platforms could prove to be a festering pool of misinformation that could disintegrate relations between the scientific community and the general public. Hence, there is felt the need to regulate and streamline the current flux of information by a joint effort of academicians and scholarly journals for better advancement in education and research.

References

1. Budapest Open Access Initiative. Read the Budapest open access Initiative. Accessed March 27, 2021. https://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/read.

2. Gasparyan AY, Yessirkepov M, Voronov AA, Koroleva AM, Kitas GD. Comprehensive approach to open access publishing: platforms and tools. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(27):e184. PMID: 31293109.

3. Directory of Open Access Journals. Accessed March 27, 2021. https://doaj.org.

4. Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Kitas GD. Open access: changing global science publishing. Croat Med J. 2013; 54(4):403–406. PMID: 23986284.

5. Alkhawtani RHM, Kwee TC, Kwee RM. Citation advantage for open access articles in European Radiology. Eur Radiol. 2020; 30(1):482–486. PMID: 31428826.

6. Zimba O, Radchenko O, Strilchuk L. Social media for research, education and practice in rheumatology. Rheumatol Int. 2020; 40(2):183–190. PMID: 31863133.

7. Haldule S, Davalbhakta S, Agarwal V, Gupta L, Agarwal V. Post-publication promotion in rheumatology: a survey focusing on social media. Rheumatol Int. 2020; 40(11):1865–1872. PMID: 32920728.

8. Goel A, Gupta L. Social media in the times of COVID-19. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020; 26(6):220–223. PMID: 32852927.

9. Joshi M, Gupta L. Preparing infographics for post-publication promotion of research on social media. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(5):e41. PMID: 33527783.

10. Gupta R, Joshi M, Gupta L. An integrated guide for designing video abstracts using freeware and their emerging role in academic research advancement. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(9):e66. PMID: 33686811.

11. Statista. Most popular social networks worldwide as of January 2021, ranked by number of active users. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/.

12. Kudchadkar SR, Carroll CL. Using social media for rapid information dissemination in a pandemic: #PedsICU and Coronavirus Disease 2019. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020; 21(8):e538–46. PMID: 32459792.

13. Gasparyan AY, Yessirkepov M, Voronov AA, Maksaev AA, Kitas GD. Article-level metrics. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(11):e74. PMID: 33754507.

14. Dijkstra S, Kok G, Ledford JG, Sandalova E, Stevelink R. Possibilities and pitfalls of social media for translational medicine. Front Med. 2018; 5:345.

15. Gupta L, Lilleker JB, Agarwal V, Chinoy H, Aggarwal R. COVID-19 and myositis - unique challenges for patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021; 60(2):907–910. PMID: 33175137.

16. Tasnim S, Hossain MM, Mazumder H. Impact of rumors and misinformation on COVID-19 in social media. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020; 53(3):171–174. PMID: 32498140.

17. Gupta L, Gasparyan AY, Misra DP, Agarwal V, Zimba O, Yessirkepov M. Information and misinformation on COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(27):e256. PMID: 32657090.

18. Gasparyan AY, Kitas GD. Best peer reviewers and the quality of peer review in biomedical journals. Croat Med J. 2012; 53(4):386–389. PMID: 22911533.

19. Misra DP, Ravindran V, Agarwal V. Integrity of authorship and peer review practices: challenges and opportunities for improvement. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33(46):e287. PMID: 30416407.

20. Ng KH, Peh WCG. Getting to know journal bibliographic databases. Singapore Med J. 2010; 51(10):757–760. quiz 761. PMID: 21103809.

21. Sinha M, Agarwal V, Gupta L. Human touch in digital education-a solution. Clin Rheumatol. 2020; 39(12):3897–3898. PMID: 33034817.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download