INTRODUCTION

It is now more than one year since the first case of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported in the Republic of Korea, and as of February 1, 2021, there were 85,567 confirmed COVID-19 cases. Among the cases, 9,063 cases (10%) are children below 19 years,

1 and no child fatality has been reported so far. This is similar to a global trend; many clinical studies have reported a low risk of infection and mild COVID-19 symptoms in children as compared to adults. According to a clinical analysis of 2,135 COVID-19 pediatric patients reported to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), most children infected with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from January 16 to February 8 in China showed mild or no symptoms. Of the 728 confirmed COVID-19 pediatric patients, 408 had mild or no symptoms, 298 cases were moderate, and only 18 cases were severe.

2 In addition, in another study that included 31 COVID-19 pediatric patients in China, 17 cases were asymptomatic or mild, and 14 children had symptoms of pneumonia. There were no severe cases, and their symptoms usually improved within 3 days.

3 Together, these findings indicate that children's clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 may be less severe than that of adults.

A study by the CDC in the United States on SARS-CoV-2 in children reported that, as of April 2, 2020, out of 149,082 COVID-19 patients, 2,572 (22%) were children (< 18 years). Of the confirmed cases, 147 were hospitalized and only 15 children were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Most cases of hospitalization were children < 1 year or with underlying diseases. 75% of the children had symptoms such as fever, cough, and shortness of breath, but they reported mild clinical manifestation.

4

A study in Korea reported milder illness in children infected with SARS-CoV-2. The study included 91 COVID-19 confirmed pediatric patients aged under 19 years in Korea from February 18 to March 31, 2020. 30% of the patients had a mild fever and 39% of the patients had a high fever (38°C or higher). More than 60% of the patients had respiratory symptoms, and there were cases of anosmia and ageusia. Some patients had abdominal pain and diarrhea. In general, of the 91 patients, 65 tested positive for an RT-PCR test, among the 85% had mild symptoms, and no case developed to a severity level that required intensive care. This study showed that pediatric infections are less symptomatic and severe with a possibility of living a normal life unaware of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

5

Based on the reports of low prevalence and severity of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infections, the government has released new SARS-CoV-2 infection response and treatment guidelines for children. Following these guidelines, pediatric patients with no or mild symptoms can be treated at home under the care of their parents.

6 This measure is meant to provide psychological stability along with treatment. In addition, some studies demonstrated that schools are not high-risk infection environments

78 and that transmission to children was mostly household, with a low percentage of school transmissions (2.4%).

9 Together, these findings could have inspired the Korean government to direct school reopening under strict infection prevention guidelines.

10 However, there is still considerable concern on the impact of school reopening on community transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

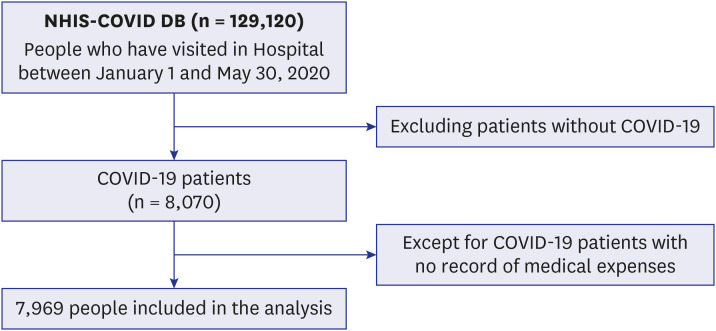

In the present study, we aimed to evaluate the appropriateness of these directives and the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections in children as compared to adults using sufficient national sample data. Therefore, we analyzed the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on children using SARS-CoV-2 national data, with the length of hospital stay (LOS), medical expenses, and ICU hospitalization as the variable outcomes. In addition, we aimed to provide informed suggestions on an efficient management plan for pediatric patients.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

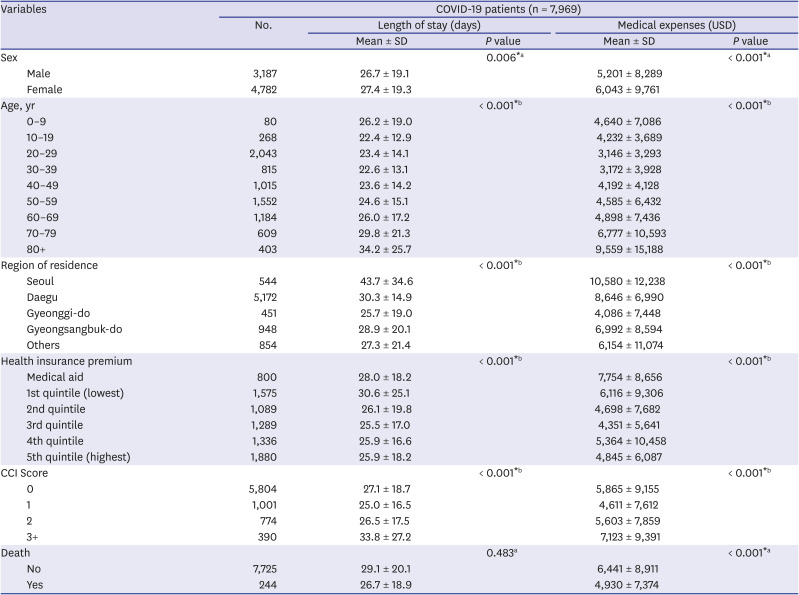

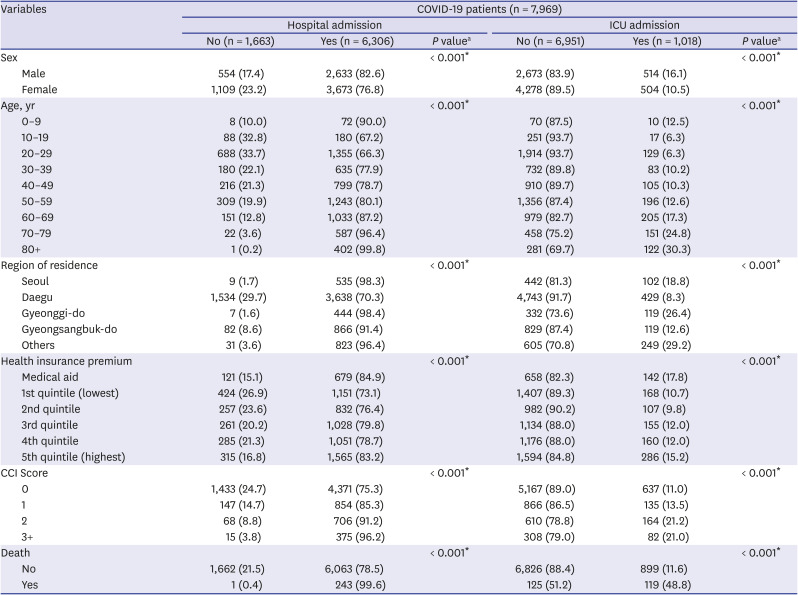

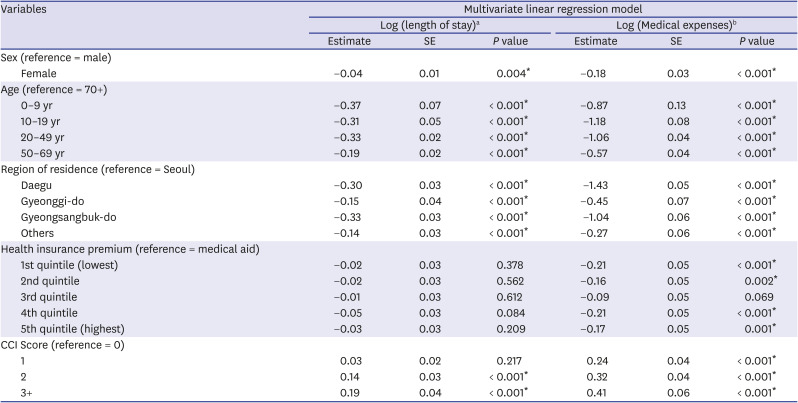

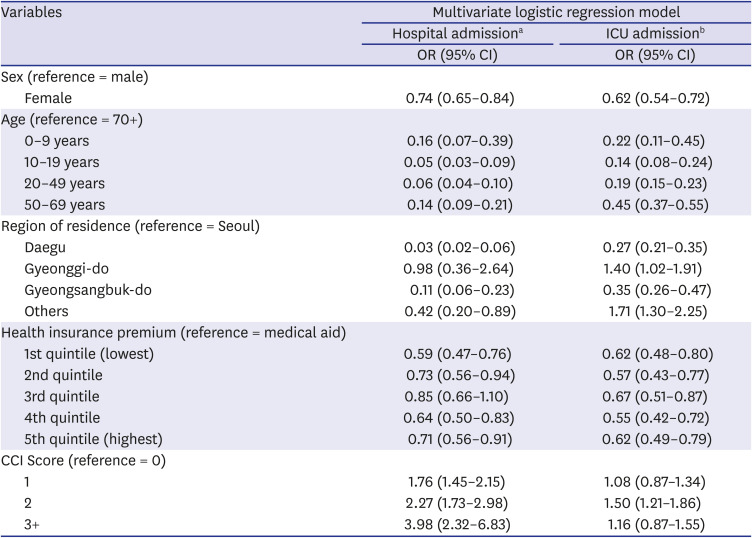

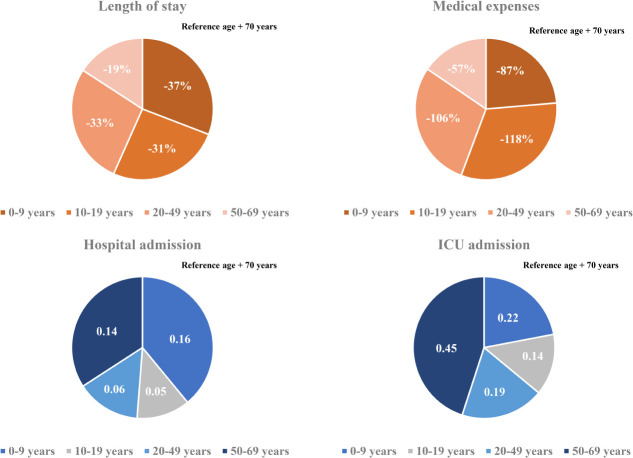

In this study, we included 7,969 Korean COVID-19 patients between January 1, 2020 and May 30, 2020. We aimed to determine the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric population compared to adults by analyzing LOS, medical expenses, hospitalization, and ICU admission. The average hospitalization days for children aged 0–9 was 26.2 days and 22.4 days for patients aged 10–19, which was about 8 days and 11.8 days shorter, respectively, than those aged 80 or older (34.2 days). Even when other variables were corrected, children aged 0–19 were found to have a shorter hospitalization period than those of older age groups. The medical expense analysis by age showed that the average medical expense for children was approximately 4,900 USD lower than that of patients aged over 80 years. The linear regression analysis also showed that children 0–9 years of age spent 87%, and those aged 10–19 spent 118% less on medical expenses than those aged 70 years and above, even after correction of other variables. The probability of hospitalization was the lowest at 10–19 years old (67.2%), which was 95% lower compared to patients aged 70 years or older, and also, their ICU admission rate was the lowest at 6.3%. On the other hand, the likelihood of hospitalization and ICU admission was the highest among children aged 0–9 years and generally patients under 50 years of age.

Our study findings were similar to those of a United States study that compared the LOS between children and adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection. This study analyzed patients who were hospitalized due to SARS-CoV-2 infection from 13 March to 17 May 2020 and compared clinical outcomes of patients aged < 24 years (n = 65) and adult patients (> 24 years, n = 60). According to the results, patients under the age of 24 stayed in the hospital for an average of 6.37 days, while the average of LOS in patients aged < 24 years was 14.77 days. Among the patients under 24 years, the average hospitalization period was 4.84 days for patients with mild symptoms, and of patients who were on a ventilator or died, the average hospital stay was 4.5 times longer (21 days) than the other patients in the same age group. In patients under 21 years of age with Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS), the average hospitalization period was 8.10 days, which was about 2 times higher than that of patients with mild symptoms.

13 Considering the results, younger patients had shorter hospital stays than adults.

In the present study, it was confirmed that the medical expenses were the lowest among patients aged 10–19 years old and highest among patients 80 years or older. A study in China has also suggested that younger patients spend less on medical expenses. The average cost of medical expenses for patients aged 0–34, including children, was the lowest (2,752 USD), while the average cost for those aged 70 and above was approximately five times higher than that of the younger age group (11,668 USD). This study assumed that most of the older people already had an underlying disease, and the presence of diseases may have influenced the high medical expenses.

14 However, in our study, even after correcting for severe underlying diseases through CCI score, the medical expense for the elderly was still high. This could be attributed to age-related immune system changes, which may be relevant not only to the age-related illnesses but also susceptibility to infectious diseases.

15

Our results also showed that the higher the age, the higher the probability of admission, and patients aged 10–19 years had the lowest admission rates. According to the recent study on the Financial Burden of Hospitalization of Children with COVID-19 in Korea, medical cost increased with age, but similar to our results, it was measured lower in children aged 11–15 years compared to 6–10 years. In addition, in terms of medication use, it was also less prescribed in patients aged 11–15 years. These results suggest that the severity of coronavirus is low in the teenage group.

16 In another study that evaluated the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients admitted in hospital and ICU in the United States, Hospital and ICU admissions rates also showed a trend of increasing with age, but the hospital admission rate for patients aged 0–19, was 2.5%, this was the lowest compared to other age groups, and there were no ICU admission cases.

17

Overall, the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients under the age of 19 years was lower than in adults, and among the younger patients, in particular, 0–9 years old are more likely to develop serious symptoms than those aged 10–19 years. Similar to our findings, some studies already in China showed that infants can develop severe illness when infected with the SARS-CoV-2. Researchers analyzed the confirmed and suspected COVID-19 pediatric patients aged 0–15 years reported from January 16 to February 8, 2020. They revealed that the proportion of COVID-19 patients with severe and critical illness among infants was highest in patients < 1 year (10.7%), 7.3% in 1–5 years, and 4.2% for the patients aged 6–10 years. Based on our results, the lower the age, the higher the probability of poor prognosis.

2 In addition, a cohort study of 25 confirmed COVID-19 pediatric patients in Hubei, China, showed that two severely ill patients were infants under the age of 1 year who had symptoms of secondary bacterial pneumonia. This study conjectured that bacterial pneumonia, which is prevalent in infancy, may be the cause of the poor prognosis.

18 Currently, in Korea, self-treatment measures have been proposed for pediatric patients with a low risk of complications among children aged 0–12 years, and from March 2021, children under the age of 8 years will be attending school every day under COVID-19 response measures. However, based on this and previous studies, the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection was lowest at the age of 10–19 years, the age for children who are less likely to develop more severe symptoms should be adjusted in the mitigation measures.

Our study confirmed that children are less likely to develop severe COVID-19 symptoms; children aged 10–19 years especially, showed a rapid recovery rate and low severity. These results showed a pattern similar to studies conducted in other countries,

19 although there were different COVID-19 hospitalization and discharge measures. This could be attributed to age-related body changes, and some studies suggested that the changes influence the body's response through the following mechanisms: First, the SARS-CoV-2 S protein adheres to the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2 and penetrates into the human body. But, because this enzyme may be less developed at a younger age, children are protected from coronavirus infection.

2021 Second, in the body SARS-CoV-2 is split into two by TMPRSS2, a protein on the surface of human cells. These cracked proteins interact with the cell surface, and RNA is brought into the cell to proliferate. Therefore, the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection is related to the activity of TMPRSS2 in the body; the expression of this protein increases significantly as the body ages, consequently, the severity of SARS-CoV-2 in the elderly. On the contrary, children have very low levels of TMPRSS2 expression, so they may be relatively protected against severe forms of COVID-19.

22 Lastly, children's immune systems response to the SARS-CoV-2 infection is different from that of adults. In the human body, there are many T cells that respond to viruses and regulate immunity. In severe cases of coronavirus, T cells decrease, resulting in decreased antiviral ability. However, there are more T cells in the children's body than in adults; the T cells suppress inflammatory reactions preventing them from developing into severe symptoms. In addition, there are many regulatory T cells, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) in the lung tissue of children; IL-10, which inhibits inflammatory factors such as the harmful cytokine interleukin 6 (IL-6), may protect the children from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

23

This study has a few limitations. First, since the residential treatment centers have been operating since March 2020, patients with mild symptoms, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 before March, were defined as hospitalized patients. Therefore, it is possible that the number of severe cases was inaccurate. In addition, there may have been errors in determining the severity because patients' clinical information by age was not contained after coronavirus infection. Nevertheless, this study attempted to increase the sensitivity of the analysis results by using four outcome variables in order to compensate for the lack of clinical information.

This study demonstrates low severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in younger patients (0–19 years) by analyzing the LOS, medical expenses, hospital, and intensive care unit admission rates as outcome variables. Since the possibility of developing severe SARS-CoV-2 infection symptoms at the age of 10–19 was the lowest, mitigation strategies should be implemented not only to children aged 0–12 years but to middle and high school students. However, in children, COVID-19 is asymptomatic, and therefore they can be silent spreaders. Therefore, mitigation strategies must include thorough management and quarantine rules. Examples are some European countries, such as Belgium, which have fully reopened schools along with exhaustive preventive measures.

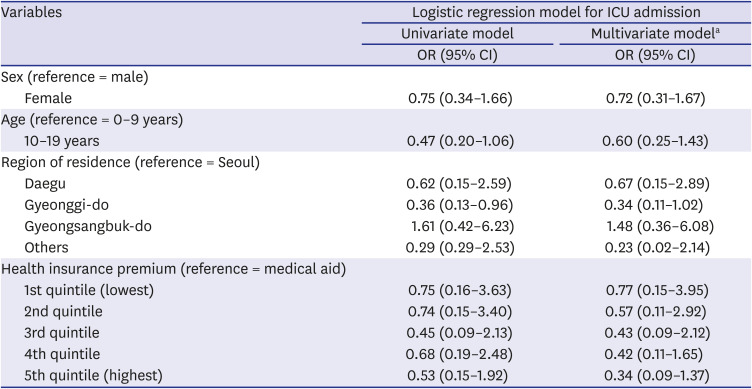

24 However, children with underlying diseases need to be protected from high-risk infection environments. This study additionally tried to determine the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children according to their social characteristics, but the results showed no statistically significant difference. However, earlier reports suggested that children's social factors may affect the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

25 For further clarification, additional studies with larger samples are required. This will help to select groups vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection among children and provide priority support for them.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download