INTRODUCTION

In DSM-5, both acute stress disorder (ASD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are characterized by exposure to traumatic events and resultant symptoms.

1 Exposure to trauma is associated with directly experiencing, witnessing, learning that the events occurred to close others, and repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of traumatic events. Symptoms of ASD and PTSD include intrusion (e.g., flashbacks, nightmares and intrusive thoughts of the traumatic events), avoidance (e.g., avoiding situations, people, and stimuli reminding of the events), negative mood and cognition (e.g., self-blame and feeling of isolation and detachment), and alterations in arousal and reactivity (e.g., hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, poor sleep, and difficulties in concentration). Although ASD and PTSD share the same symptom criteria, there are differences between them including symptom duration and common symptoms. While duration of symptoms is not lasting for more than 1 month and less degree of overall symptoms is common, more dissociative symptoms are reported in ASD.

12

Although there have been few studies regarding the incidence or the prevalence of ASD in the general population, previous studies regarding the prevalence of PTSD in the general population existed. Since the late 1990s, the World Health Organization (WHO) has collected international epidemiological information on mental health disorders using the World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys and reported that the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in 17 countries ranged from a low of 0.3% in China to 6.1% in New Zealand.

3 In the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) study, using the WHO WMH Survey version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults aged 18 or older was estimated at 6.8% in the U.S.

45 Based on data from the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), using a modified version of the WHO CIDI, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adolescents aged 13–18 was estimated up to 5.0%.

6 Using data from 1,986 subjects in the Northern Ireland Study of Health and Stress, Ferry et al.

7 reported that the 1-year prevalence rate of PTSD in Northern Ireland was 5.1% in 2008. In a series of the Epidemiological Survey of Psychiatric Illnesses in Korean studies using the Korean version of CIDI, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD ranged from 1.2 to 1.6% and the 1-year prevalence ranged from 0.4 to 0.7%.

8 Although the incidence of PTSD after a single traumatic event (e.g. natural disaster, combat, violence, etc.) or among selected subjects has been reported in previous studies,

910111213 however, there have been no studies regarding the annual incidence of ASD and PTSD in the general population. As incidence is defined by the number of new cases of disease among the number of susceptible persons in a given location and over a particular span of time and more useful than prevalence in understanding the etiology and the risk factors of disease,

14 we chose incidence rather than prevalence in order to identify factors related to ASD and PTSD.

Although ASD was first included in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

15 there have been limited information on direct medical costs of ASD in the general population. Most previous studies have been performed in order to estimate the cost of PTSD. Based on the survey of 230 clients receiving NHIS for PTSD following the London Bombings in July 2005, Buljan

16 estimated direct medical cost of PTSD up to 1,495,012 US dollars (USD), which accounts for 6,500 USD per person. Wang et al.

17 used the Veterans Health Association (VHA) database from 2010 to 2015 and estimated direct medical cost of PTSD as 16,750 USD per person. Based on private insurance and Medicaid data, Ivanova et al.

18 suggested that direct health care costs of PTSD could be estimated at 10,960–18,753 USD per person. Bothe et al.

19 used claims data from a German research database and reported 15,537 USD per person as direct medical cost for 3 years. In Ferry et al.

7's study, direct medical cost was 49,133,629 USD, which accounts for 656 USD per person. To our best knowledge, the direct medical cost of PTSD in Korea has not been reported.

Because a collaborative care strategy would be essential for the successful treatment of common mental disorders like ASD and PTSD in primary care settings,

20 there remains a need for overall information on ASD and PTSD across primary care settings. The Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) is the only insurer and has been operating a public database, which is the National Health Insurance Database (NHID), since 2012.

21 NHID have contained almost all medical claims data for the Korean population and have provided information on health care utilization, health screening, socio-demographics, dates of death, and diagnostic codes using Korean Standard Classification of Diseases diagnostic codes, which has been based on International Classification of Disease, 10th edition (ICD-10).

22 Given the paucity of existing information on the incidence and economic burden of PTSD, NHID would be an important resource for examining the epidemiology of ASD and PTSD. The aims of the current study were to ascertain the number of people who were newly diagnosed with ASD and PTSD annually, and to estimate direct medical cost in people with ASD and PTSD.

Go to :

RESULTS

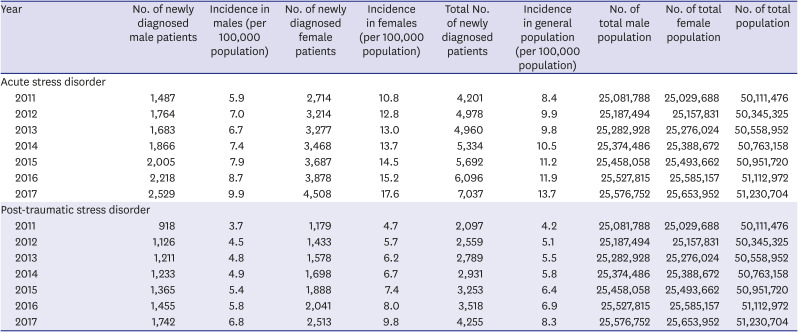

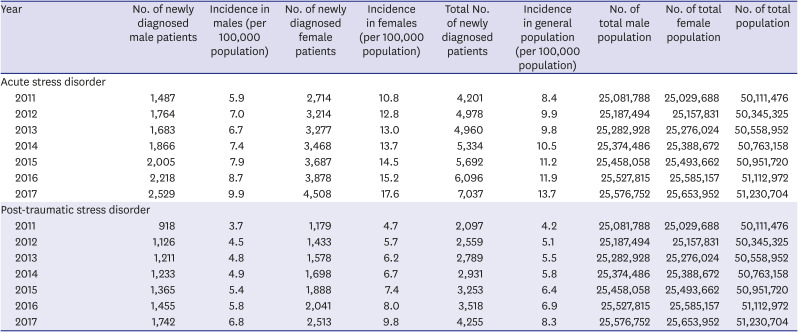

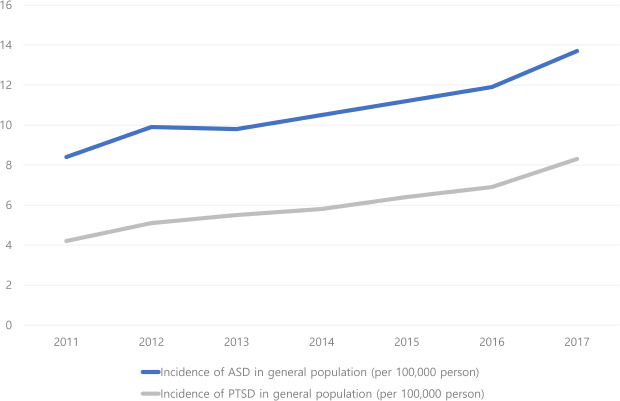

From 2011 to 2017, the total number of patients with ASD and PTSD and the incidence of ASD and PTSD were increased. In case of ASD, except 2013, the number of newly diagnosed patients increased every year. The incidence rate of ASD was also increased, while there was a decrease from 2012 to 2013. In the case of PTSD, the number of newly diagnosed patients and the incidence rate were continuously increased. The incidence rate of ASD was 8.4 per 100,000 population in 2011 and reached 13.7 per 100,000 population in 2017. In addition, the total incidence rate of PTSD was 4.2 per 100,000 population in 2011 and 8.3 per 100,000 population in 2017. During this period, the number of female patients with ASD or PTSD was higher than the number of male patients (

Table 1).

Table 1

Number of patients and incidence of acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in Korea from 2011 to 2017 (per 100,000 population)

|

Year |

No. of newly diagnosed male patients |

Incidence in males (per 100,000 population) |

No. of newly diagnosed female patients |

Incidence in females (per 100,000 population) |

Total No. of newly diagnosed patients |

Incidence in general population (per 100,000 population) |

No. of total male population |

No. of total female population |

No. of total population |

|

Acute stress disorder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2011 |

1,487 |

5.9 |

2,714 |

10.8 |

4,201 |

8.4 |

25,081,788 |

25,029,688 |

50,111,476 |

|

2012 |

1,764 |

7.0 |

3,214 |

12.8 |

4,978 |

9.9 |

25,187,494 |

25,157,831 |

50,345,325 |

|

2013 |

1,683 |

6.7 |

3,277 |

13.0 |

4,960 |

9.8 |

25,282,928 |

25,276,024 |

50,558,952 |

|

2014 |

1,866 |

7.4 |

3,468 |

13.7 |

5,334 |

10.5 |

25,374,486 |

25,388,672 |

50,763,158 |

|

2015 |

2,005 |

7.9 |

3,687 |

14.5 |

5,692 |

11.2 |

25,458,058 |

25,493,662 |

50,951,720 |

|

2016 |

2,218 |

8.7 |

3,878 |

15.2 |

6,096 |

11.9 |

25,527,815 |

25,585,157 |

51,112,972 |

|

2017 |

2,529 |

9.9 |

4,508 |

17.6 |

7,037 |

13.7 |

25,576,752 |

25,653,952 |

51,230,704 |

|

Post-traumatic stress disorder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2011 |

918 |

3.7 |

1,179 |

4.7 |

2,097 |

4.2 |

25,081,788 |

25,029,688 |

50,111,476 |

|

2012 |

1,126 |

4.5 |

1,433 |

5.7 |

2,559 |

5.1 |

25,187,494 |

25,157,831 |

50,345,325 |

|

2013 |

1,211 |

4.8 |

1,578 |

6.2 |

2,789 |

5.5 |

25,282,928 |

25,276,024 |

50,558,952 |

|

2014 |

1,233 |

4.9 |

1,698 |

6.7 |

2,931 |

5.8 |

25,374,486 |

25,388,672 |

50,763,158 |

|

2015 |

1,365 |

5.4 |

1,888 |

7.4 |

3,253 |

6.4 |

25,458,058 |

25,493,662 |

50,951,720 |

|

2016 |

1,455 |

5.8 |

2,041 |

8.0 |

3,518 |

6.9 |

25,527,815 |

25,585,157 |

51,112,972 |

|

2017 |

1,742 |

6.8 |

2,513 |

9.8 |

4,255 |

8.3 |

25,576,752 |

25,653,952 |

51,230,704 |

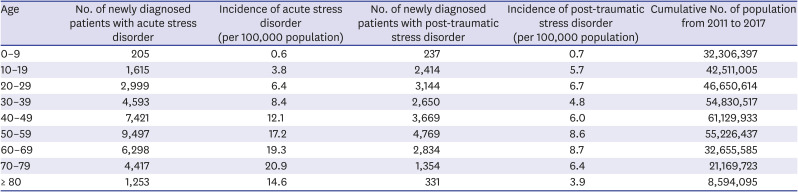

The incidence of ASD and PTSD according to age groups was presented in

Table 2. The highest number of newly diagnosed patients were found in the 50–59 years of age group in both ASD and PTSD. However, considering the number of population in age groups, the incidence rate was highest in 70–79 years of age group in ASD, while the incidence rate of PTSD was highest in the 60–69 years of age group.

Table 2

Number of patients and incidence of acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder in Korea from 2011 to 2017 by age groups

|

Age |

No. of newly diagnosed patients with acute stress disorder |

Incidence of acute stress disorder (per 100,000 population) |

No. of newly diagnosed patients with post-traumatic stress disorder |

Incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (per 100,000 population) |

Cumulative No. of population from 2011 to 2017 |

|

0–9 |

205 |

0.6 |

237 |

0.7 |

32,306,397 |

|

10–19 |

1,615 |

3.8 |

2,414 |

5.7 |

42,511,005 |

|

20–29 |

2,999 |

6.4 |

3,144 |

6.7 |

46,650,614 |

|

30–39 |

4,593 |

8.4 |

2,650 |

4.8 |

54,830,517 |

|

40–49 |

7,421 |

12.1 |

3,669 |

6.0 |

61,129,933 |

|

50–59 |

9,497 |

17.2 |

4,769 |

8.6 |

55,226,437 |

|

60–69 |

6,298 |

19.3 |

2,834 |

8.7 |

32,655,585 |

|

70–79 |

4,417 |

20.9 |

1,354 |

6.4 |

21,169,723 |

|

≥ 80 |

1,253 |

14.6 |

331 |

3.9 |

8,594,095 |

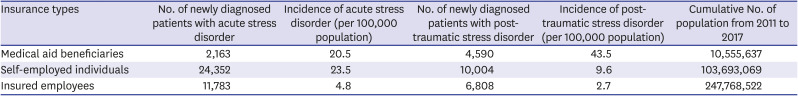

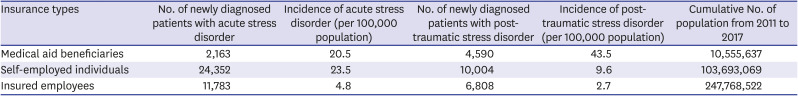

The incidence rate according to insurance types was presented in

Table 3. The highest number of newly diagnosed patients was found in the self-employed individuals group in both ASD and PTSD. However, while the incidence rate of ASD was highest in self-employed individuals groups, that of PTSD was highest in the medical aid beneficiaries group.

Table 3

Number of patients and incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder in South Korea from 2011 to 2017 by insurance type (per 100,000 population)

|

Insurance types |

No. of newly diagnosed patients with acute stress disorder |

Incidence of acute stress disorder (per 100,000 population) |

No. of newly diagnosed patients with post-traumatic stress disorder |

Incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (per 100,000 population) |

Cumulative No. of population from 2011 to 2017 |

|

Medical aid beneficiaries |

2,163 |

20.5 |

4,590 |

43.5 |

10,555,637 |

|

Self-employed individuals |

24,352 |

23.5 |

10,004 |

9.6 |

103,693,069 |

|

Insured employees |

11,783 |

4.8 |

6,808 |

2.7 |

247,768,522 |

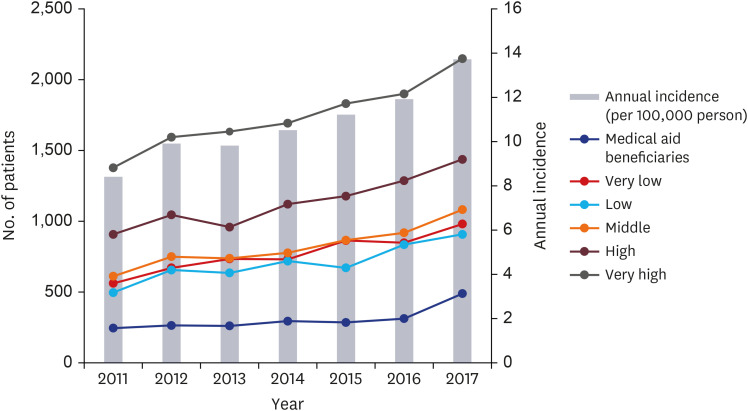

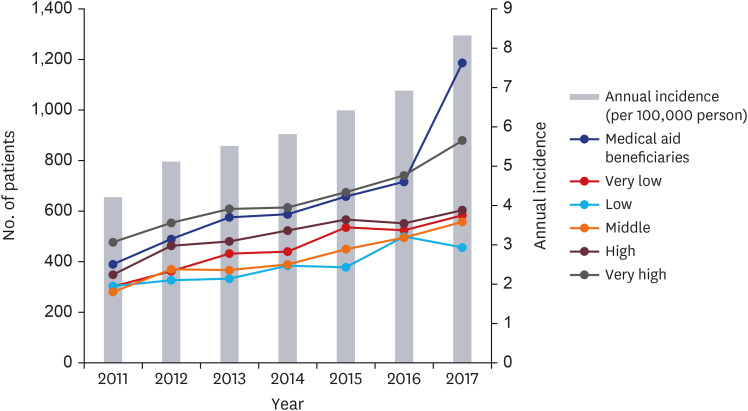

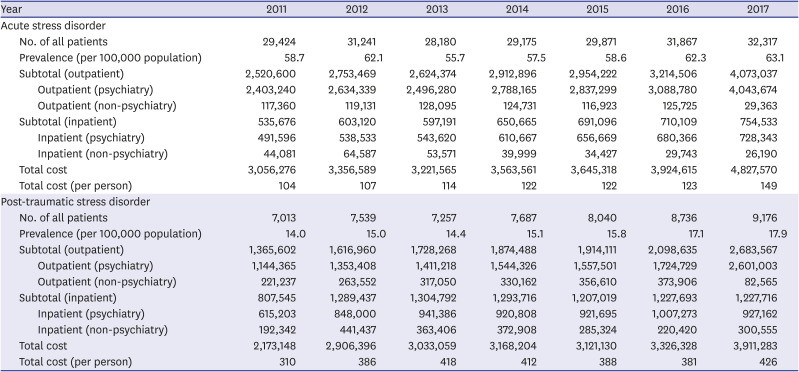

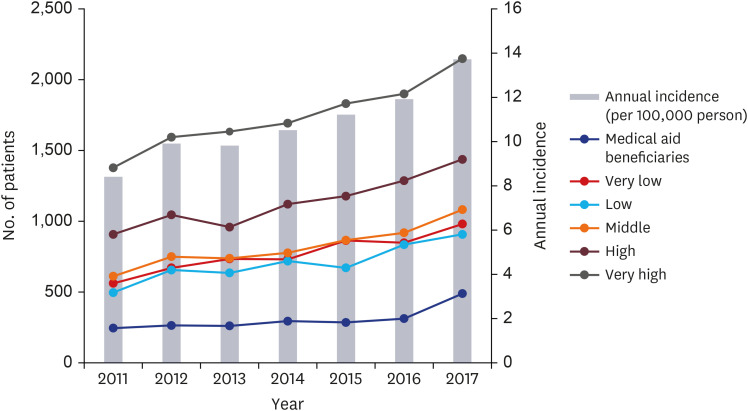

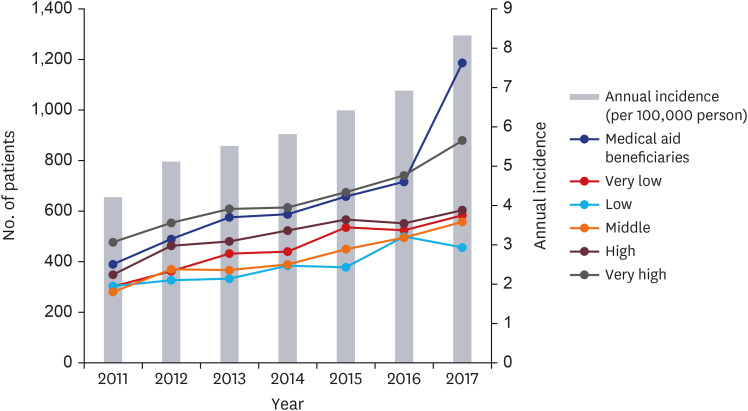

When we divided patients with ASD into 6 groups by income (i.e., very high, high, middle, low, very low, and medical aid beneficiaries group), the number of patients was highest in the very high income group and lowest in the medical aid beneficiaries group (

Fig. 1). However, in the case of PTSD, this tendency was not found. Although the order of the number of patients by year seemed to be mixed in part, the highest number of patients was found in the following order: medical aid beneficiaries group, very high income group, high income group, very low income group, middle income group, and low income group in 2017 (

Fig. 2). As the exact number of population in any groups by year was not available, therefore the changes in incidence of ASD and PTSD in 6 groups could not be presented.

| Fig. 1 Number of patients according to income level and annual incidence (per 100,000 capita) of acute stress disorder in South Korea from 2011 to 2017.

|

| Fig. 2 Number of patients according to income level and annual incidence (per 100,000 capita) of post-traumatic stress disorder in South Korea from 2011 to 2017.

|

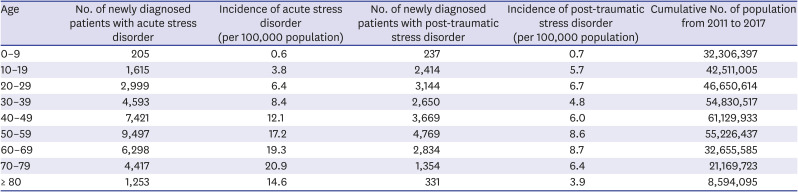

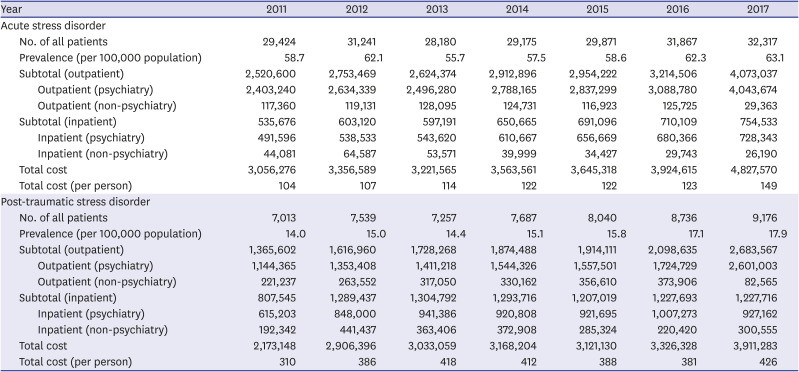

We estimated prevalence and direct medical cost of patients with ASD and PTSD from 2011 to 2017. The number of all patients with ASD and PTSD and the prevalence of ASD and PTSD in 2017 were higher than those in 2011. In the case of ASD, higher number of all patients were found in order of 2017, 2016, 2012, 2015, 2011, 2014, and 2013. In addition, higher prevalence was found in order of 2017, 2016, 2012, 2011, 2015, 2014, and 2013, respectively. In the case of PTSD, the number of all patients and prevalence were continuously increased except in 2012. Total direct medical cost of ASD was continuously increased except in 2013 and the total direct medical cost per person was 149 USD in 2017. In addition, total direct medical cost of PTSD was continuously increased except in 2015 and the total direct medical cost per person reached 426 USD. In both ASD and PTSD, most direct medical cost was claimed by outpatient clinics and psychiatric department inpatient units (

Table 4).

Table 4

Medical costs and prevalence of acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder in South Korea from 2011 to 2017

|

Year |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

|

Acute stress disorder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No. of all patients |

29,424 |

31,241 |

28,180 |

29,175 |

29,871 |

31,867 |

32,317 |

|

Prevalence (per 100,000 population) |

58.7 |

62.1 |

55.7 |

57.5 |

58.6 |

62.3 |

63.1 |

|

Subtotal (outpatient) |

2,520,600 |

2,753,469 |

2,624,374 |

2,912,896 |

2,954,222 |

3,214,506 |

4,073,037 |

|

|

Outpatient (psychiatry) |

2,403,240 |

2,634,339 |

2,496,280 |

2,788,165 |

2,837,299 |

3,088,780 |

4,043,674 |

|

|

Outpatient (non-psychiatry) |

117,360 |

119,131 |

128,095 |

124,731 |

116,923 |

125,725 |

29,363 |

|

Subtotal (inpatient) |

535,676 |

603,120 |

597,191 |

650,665 |

691,096 |

710,109 |

754,533 |

|

|

Inpatient (psychiatry) |

491,596 |

538,533 |

543,620 |

610,667 |

656,669 |

680,366 |

728,343 |

|

|

Inpatient (non-psychiatry) |

44,081 |

64,587 |

53,571 |

39,999 |

34,427 |

29,743 |

26,190 |

|

Total cost |

3,056,276 |

3,356,589 |

3,221,565 |

3,563,561 |

3,645,318 |

3,924,615 |

4,827,570 |

|

Total cost (per person) |

104 |

107 |

114 |

122 |

122 |

123 |

149 |

|

Post-traumatic stress disorder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No. of all patients |

7,013 |

7,539 |

7,257 |

7,687 |

8,040 |

8,736 |

9,176 |

|

Prevalence (per 100,000 population) |

14.0 |

15.0 |

14.4 |

15.1 |

15.8 |

17.1 |

17.9 |

|

Subtotal (outpatient) |

1,365,602 |

1,616,960 |

1,728,268 |

1,874,488 |

1,914,111 |

2,098,635 |

2,683,567 |

|

|

Outpatient (psychiatry) |

1,144,365 |

1,353,408 |

1,411,218 |

1,544,326 |

1,557,501 |

1,724,729 |

2,601,003 |

|

|

Outpatient (non-psychiatry) |

221,237 |

263,552 |

317,050 |

330,162 |

356,610 |

373,906 |

82,565 |

|

Subtotal (inpatient) |

807,545 |

1,289,437 |

1,304,792 |

1,293,716 |

1,207,019 |

1,227,693 |

1,227,716 |

|

|

Inpatient (psychiatry) |

615,203 |

848,000 |

941,386 |

920,808 |

921,695 |

1,007,273 |

927,162 |

|

|

Inpatient (non-psychiatry) |

192,342 |

441,437 |

363,406 |

372,908 |

285,324 |

220,420 |

300,555 |

|

Total cost |

2,173,148 |

2,906,396 |

3,033,059 |

3,168,204 |

3,121,130 |

3,326,328 |

3,911,283 |

|

Total cost (per person) |

310 |

386 |

418 |

412 |

388 |

381 |

426 |

Go to :

DISCUSSION

To our best knowledge, the current study is the first one reporting the incidence of ASD and PTSD in the general population using the NHID in Korea. From 2011 to 2017, the annual incidence rate of ASD and PTSD in Korea increased continuously. The annual incidence of ASD was 8.4 per 100,000 population in 2011 and reached 13.7 per 100,000 population in 2017. During the same period, the annual prevalence rate of ASD was in the range from 55.7 to 63.1 per 100,000 population. The annual incidence rate of PTSD was 4.2 per 100,000 population in 2011 and 8.3 per 100,000 population in 2017. The annual prevalence rate of PTSD ranged from 14.0 to 17.9 per 100,000 population.

These increases may be partly explained by recent changes in social perception of trauma and treatment of resultant psychiatric symptoms as essential, according to increased mass media reports on trauma caused by natural or man-made disasters (e.g., Sewol ferry disaster) and their enduring sequelae including ASD and PTSD in Korea.

24 Although social stigma against psychiatric illness still existed.

25 The annual prevalence of PTSD in the general population in the current study is lower than that in previous studies in the U.S., Northern Ireland, and Korea.

45678 This discrepancy might be due to differences in study methods and biased sample. As results in the current study were derived from claims data, only those who intended to be diagnosed and treated would be included as patients in NHID. Considering social stigma against psychiatric illness,

25 it seemed that most patients might tolerate ASD and PTSD and remain untreated. In addition, psychosocial treatment outside medical settings including public counselling centers (e.g., Sunflower Center for victims of sexual violence, Smile Center for victims of crime, Mental Health Welfare Center or Disaster Psychology Recovery Support Center for victims of natural disaster, etc.) and private counselling centers should be considered.

In partial accordance with previous studies,

4568 the number of patients and the incidence rate in females was higher than those in males, in both ASD and PTSD. In the NCS-R study, the past-year prevalence was higher in females (5.2%) than in males (1.8%).

45 In a previous study using data from the NCS-A, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adolescents was also higher in females (8.0%) than in males (2.3%).

6 In the Epidemiological Survey of Psychiatric Illnesses in Korea in 2016, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD was higher in females (1.8%) than in males (1.3%). The 1-year prevalence of PTSD in females (0.7%) was also higher than that in males (0.2%).

8 In addition, higher prevalence was found in order of 60–69, 30–39, > 70 and 50–59, and 40–49 and 18–29 years of age groups. Among 3 income groups (i.e., low, middle, and high), the highest prevalence was found in the low income group.

8 Our results that the highest incidence rate of PTSD was in the 60–69 years of age group and in the medical aid beneficiaries group were in partial accordance with the results of this study.

In the current study, while the number of patients with ASD was highest in the very high income group and lowest in the medical aid beneficiaries group consistently, a higher number of patients with PTSD was found in order of medical aid beneficiaries group, very high income group, high income group, very low income group, middle income group, and low income group in 2017. Considering that the number of population in each of the 5 income quintile groups was approximately 7 times more than that in the medical beneficiaries group, we could speculate that actual incidence of ASD and PTSD was also highest in the medical beneficiaries group among the 6 groups. In a previous study, low socioeconomic status was related to increased risk of interpersonal violence including child abuse and sexual assaults.

26 In addition, low income made one to live in an environment where it was easy be exposed to natural disasters.

27 Although it seemed to be difficult to specify a direct relationship between low socio-economic status and trauma-related psychiatric conditions including ASD and PTSD, there have been a few studies reporting an association between economic disadvantage and PTSD.

282930 Interestingly, among 5 income quintile groups in self-employed individuals and insured employees, the number of patients and incidence in both ASD and PTSD was highest in rather very high income group in the current study. This bimodal distribution in the incidence of ASD and PTSD in Korea according to income level might be explained by higher rate of traumatic experience in medical aid beneficiaries group and higher utilization rate in very high income level.

In the current study, annual direct medical cost of ASD was continuously increased except in 2013 and annual direct medical cost per person was 149 USD in 2017. In addition, annual direct medical cost of PTSD was continuously increased except in 2015 and annual direct medical cost per person reached 426 USD. In both ASD and PTSD, most direct medical cost was claimed by outpatient clinics and psychiatric department inpatient units. Compared by results from other countries, the direct medical cost for ASD and PTSD per person in Korea seemed to be low.

Based on the survey of 230 clients with NHIS for PTSD following acute and seriously life-threatening trauma, that is the London Bombings in July 2005, Buljan

16 estimated direct medical cost included 167,411 USD for screening and assessment, 493,467 USD for treatment, 169,327 USD for health services, 558,690 USD for hospitalization, 6,401 USD for medicines, 77,359 USD for private sector, and 22,357 USD for voluntary sector. Total direct medical cost for 230 clients was 1,495,012 USD, which accounts for 6,500 USD per person. Using data of 492,546 patients with PTSD in the VHA database from 2010 to 2015, Wang et al.

17 reported that total 16,750 USD including 5,486 USD for inpatient costs, 10,057 USD for outpatient treatment costs, and 1,207 USD for pharmacy costs per person would be needed for treatment of PTSD.

Using claims data of 18,834 patients with PTSD including Medicaid data in 3 states from 1999 to 2007 and private insurance data in 55 large, self-insured companies’ data from 1999 to 2008, Ivanova et al.

18 estimated direct health care costs of PTSD as 10,960-18,753 USD including 8,637-13,183 USD for treatment in medical department and 2,422–5,569 USD for prescription drugs per person. In this study, mental health-related direct medical cost was 3,489 USD in private insurance and 11,395 USD in Medicaid groups, respectively. Bothe et al.

19 used claims data of 12,887 patients with PTSD from a German research database and reported that PTSD subjects used 15,537 USD per person as direct medical cost for 3 years after diagnosis. In Ferry et al.

7's study, based on the estimate of approximately 74,935 individuals with PTSD, direct medical cost including cost of service visits and cost of medication was 49,133,629 USD, which accounts for 656 USD per person. However, to our best knowledge, there have been no studies regarding annual direct medical cost of ASD and PTSD in the general population. As different approaches were used to estimate the direct cost of PTSD across countries in which various health care systems and databases existed, results of previous studies should be interpreted cautiously.

There were a few limitations in the current study. As the current study used claims data from hospitals, patients who began treatment outside of a hospital were not included, therefore, the results from this study would not reflect the precise incidence of ASD and PTSD. Another limitation is that duplicates of ASD and PTSD were not removed to estimate incidence and prevalence, which could have affected the results of the current study. Thus, further research is warranted to replicate the current study by excluding duplicates of ASD and PTSD. In addition, as the current study was based on rather diagnostic codes recorded in claims data than standard interviews, diagnostic scales, and laboratory data, the diagnostic validity could be low and biased. Nevertheless, given the global lack of evidence relating to ASD and PTSD, the current study has the strength to examine the diagnosed incidence for ASD and PTSD using data recorded by physician representative of the national population.

As global interest in trauma and related sequelae has been growing recently, proper information on ASD and PTSD will not only allow us to accumulate more knowledge about these disorders themselves but also lead to more appropriate therapeutic interventions by improving the ability to cope with trauma-related psychiatric sequelae. Considering increasing incidence and direct medical cost of ASD and PTSD despite social stigma, public education regarding trauma and its related sequelae as well as evidence-based treatment in regional trauma centers should be provided.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download