INTRODUCTION

Based on the 2012 revised international Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) has currently been defined as the necrotising vasculitis without definite immune-complex deposition. AAV primarily affects small vessels, including small intraparenchymal arteries, arterioles, capillaries and venules and occasionally medium-sized arteries and veins.

1 In addition, AAV can be further classified three subtypes based on pathogenesis, histological findings, clinical symptoms and signs and laboratory results such as microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and eosinophilic GPA (EGPA).

12

Each systemic vasculitis has its own typical sex difference in the incidence: for instance, among large vessel vasculitis, giant cell arteritis has the male to female ratio of 1:3, whereas Takayasu arteritis has the male to female ratio of 1:9.

3 Moreover, each systemic vasculitis has a sex differences in the clinical features: for instance, with regard to Korean patients with Behcet's disease, female patients exhibited more frequently genital ulcers, peripheral arthritis, and inflammatory low back pain, whereas male patients showed a higher frequency of skin lesions.

4 There was a previous study pertaining to the sex difference in AAV patients, which reported that male patients were vulnerable to the progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) compared to female patients. However, this study included only ANCA-positive AAV patients with histologically proven pauci-immune necrotising glomerulonephritis. For this reason, the results could not be generalised to all AAV patients.

5 Also, given the ethnic and geographical differences affecting both the clinical manifestation and the poor outcomes of AAV, a need for a study investigating the sex difference in Korean patients with AAV is still raised but there has been no study on it to date. Hence, in this study, we investigated and compared the initial clinical features at diagnosis and the poor outcomes during follow-up in Korean patients with AAV based on sex.

DISCUSSION

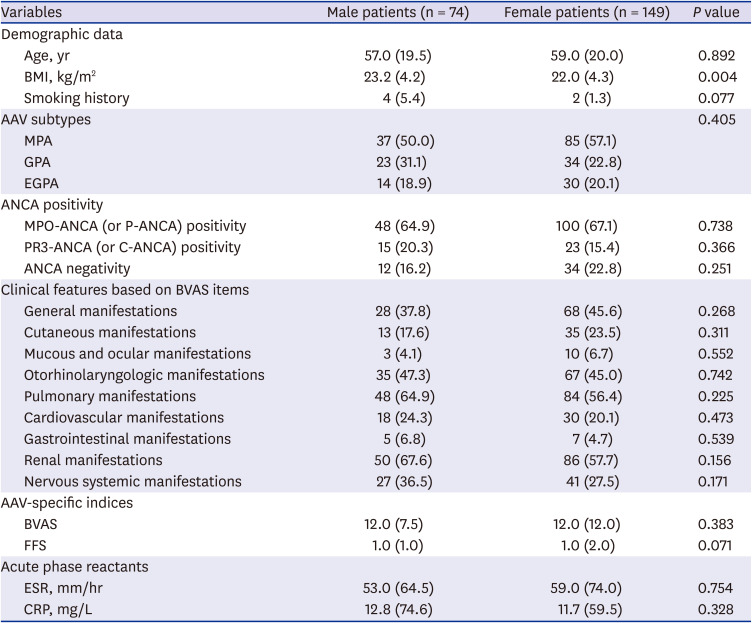

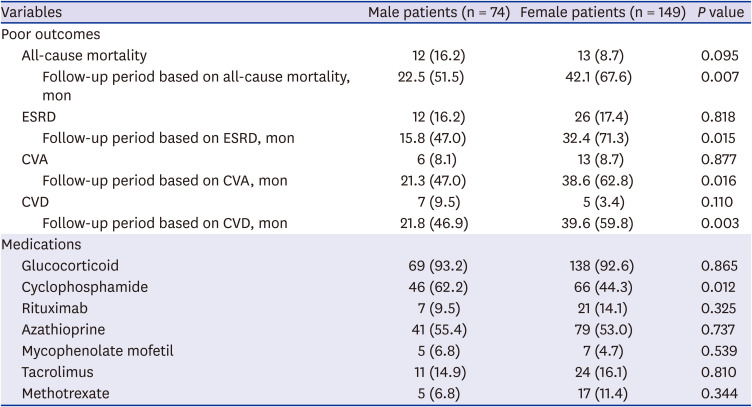

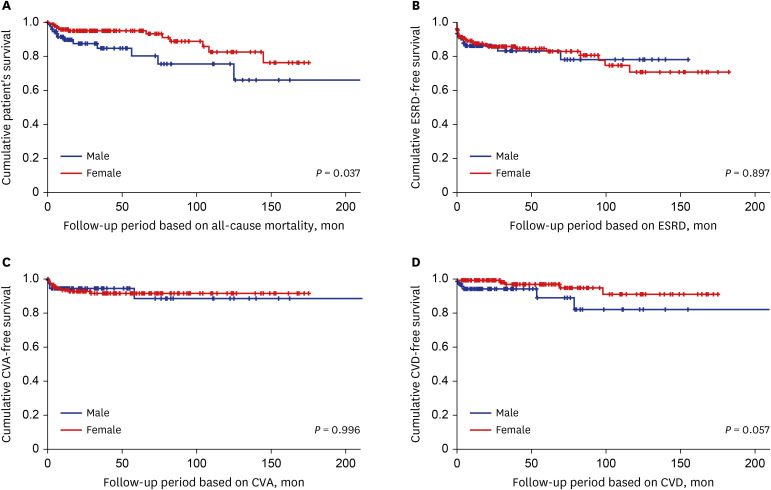

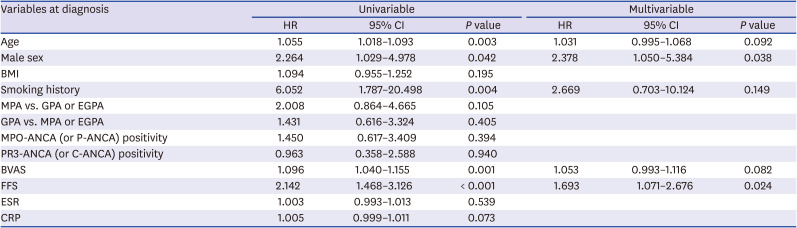

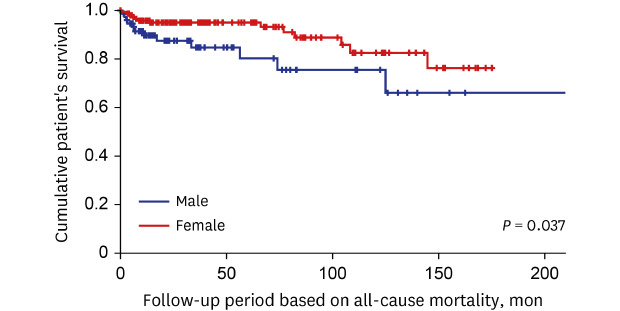

In this study comparing the clinical features based on the sex difference in AAV patients, we discovered the following three new findings. First, at the time of diagnosis, the clinical features and laboratory related to AAV, such as AAV subtypes, ANCA positivity, clinical manifestations and AAV-specific indices, did not significantly differ between male and female patients. Second, during the follow-up period, male patients exhibited a significantly lower cumulative patients' survival rate compared to female patients. Third, male sex together with FFS was proved to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality during the follow-up period in AAV patients.

Only male sex itself does not seem to simply increase the rate of all-cause mortality in this study. A previous study reported introduced dietary risks, tobacco smoking, high BMI, high blood pressure and high fasting plasma glucose as the most common risk factors for mortality. However, male sex itself was not clearly defined as a primary risk factor for mortality.

9 Another previous study denied the fact that the life expectancy of men was meaningfully lower than that of women. Instead, it suggested the different clinical features based on the sex difference.

10 Meanwhile, although there were no differences in clinical manifestations at diagnosis between male and female AAV patients, in the multivariable Cox analysis, male sex was an independent predictor of all-cause mortality during follow-up. It is difficult to suggest the exact mechanism, but it can be assumed that in a condition with persistent AAV, male patients are more frequently exposed to situations that may increase the rate of all-cause mortality compared to female patients. The result that cyclophosphamide had been administered to male patients more frequently than female patients during the follow-up period may support our assumption.

At diagnosis, male patients showed a higher mean BMI than female patients.

We wondered whether a high BMI in male patients has influenced an increase in all-cause mortality compared to female patients. To get the clue to prove this, we compared BMI between survived and dead patients with AAV and found that there was no significant difference between the two groups (22.1 vs. 23.0 kg/m

2,

P = 0.292). In addition, in the multivariable Cox analysis, BMI was not significantly associated with all-cause mortality (

Table 3). Why did not the high calculated BMI in male patients contribute to an increased all-cause mortality rate in male patients? According to the previous studies, the rate of all-cause mortality showed a U-shape with BMI between 22.5 and 25 kg/m

2 as a reference range: the rate of all-cause mortality tended to increase not only in the BMI range of below 22.5 (or 25) kg/m

2 but also in BMI range of above 25 kg/m

2.

1112 However, unlike the previous studies, in this study, the BMI range, where the largest number of AAV patients died (44.0%), was between 22.1 and 25.0 kg/m

2. It could be assumed that this discrepancy was derived from the different study-subjects between general people and AAV patients and furthermore, it might offset the high calculated BMI in male patients from contributing to an increased all-cause mortality rate.

A previous study, male sex was significantly associated with ESRD occurrence compared to female sex in AAV patients with histologically proven pauci-immune necrotising glomerulonephritis.

5 However, unlike the previous study, no significant difference in the cumulative ESRD-free survival rate between male and female patients in this study. Although not all patients with renal involvement underwent renal biopsy, to reproduce the result of the previous study, we included only AAV patients with renal involvement (50 men and 86 women) and analysed it again. However, we could find no significant difference in the cumulative ESRD-free survival rates between male and female patients during the follow-up period based on ESRD (

P = 0.994) (

Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, although focusing on AAV patients with renal involvement, we conclude that the male sex was turned out to be not a good predictor of ESRD during follow-up.

We wondered whether male sex may differently affect the cumulative patients' survival rates among AAV-subtypes. Therefore, we conducted the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for comparing the cumulative patients' survival rates between male and female patients in each AAV subtypes. Among MPA patients, male patients exhibited a significantly lower cumulative survival rate than female patients. However, no significant difference in the cumulative survival rates was observed between male and female patients among GPA patients (

Supplementary Fig. 2). On the other hand, since all EGPA patients survived during the follow-up period, the analysis regarding the clinical significance of sex for all-cause mortality was not performed in EGPA patients. With these results, we conclude that the male sex could reduce significantly the cumulative patients' survival rates in MPA patients compared to GPA patients. However, in real clinical settings, since there are not a few cases where the differential diagnosis between MPA and GPA may be difficult, we intend to maintain the current title including AAV patients rather than MPA patients.

In this study, variables with

P value less than 0.005 in the univariable Cox hazard model analysis were restrictively included in the multivariable analysis. However, since we cannot ignore the variables that were found to be associated with mortality in previous studies, we considered including these variables in multivariate analysis. Since BMI showed a ‘U shape’ contribution to the rate of all-cause mortality, BMI cannot be included in the multivariable analysis. Whereas, ANCA type was reported to be associated with the mortality rate or the infectious cause of death in AAV patients.

13 Therefore, we consider including MPO-ANCA (or P-ANCA) and PR3-ANCA (or C-ANCA) in the multivariable Cox hazards model analysis, however, both of them exhibited too low statistical significance in the univariable analysis to be included in the multivariable analysis. On the other hand, CRP tended to be significantly associated with all-cause mortality during the follow-up period (

P = 0.073) and furthermore, an index consisting of CRP and other variables was reported to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in AAV patients.

14 Therefore, we conducted the multivariable Cox hazards model analysis by including CRP. However, similar to the results from

Table 3, only male sex and FFS at diagnosis exhibited statically significant HR in the multivariable analysis, despite the addition of CRP. Therefore, we decided to maintain the results of

Table 3.

The retrospective design might weaken the power of the clinical implication of the sex difference that our study provided. Also, the number of patients was not large enough to represent all Korean patients with AAV. However, this study might be valuable in that this is the first study which provided information regarding the differences in the clinical features and prognosis in the course of AAV between male and female AAV patients in Korea. Also, the limitation of the monocentric study may paradoxically minimise the inter-centric variation or bias, which could enhance the reliability of our study. Most deaths from septic shock or cancer were more frequent than death from persistent haemoptysis or damage to major organs such as the brain and heart. However, since there were many cases in which it was impossible to accurately classify the cause of their death, this study used the item of all-cause mortality without classifying death by cause, which was an additional limitation of this study. We believe that a prospective future study with a larger number of patients by recruiting the institutes, where the same inclusion criteria can be applied and the electronic medical records can be shared, will provide more reliable and valuable information.

In conclusion, male sex did not affect the clinical features at diagnosis, however, it increased the rate of all-cause mortality during the follow-up of AAV and was proved to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in AAV patients.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download