INTRODUCTION

The B-cell receptor (BCR) is a transmembrane receptor that controls the differentiation and function of normal B-cells, which is located on the cell surface of B-lymphocytes [

1]. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a membrane-proximal tyrosine kinase that plays a crucial role in the BCR signaling cascade [

2]. The dysregulation of BCR signaling (dysregulated BTK activity) promotes the cancer cells to evade apoptosis, resulting in proliferation and survival of malignant B-cells [

3]. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults, characterized by progressive accumulation of monoclonal B-lymphocytes. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) consist of a complex group of cancers arising primarily from B-lymphocytes (85% of cases) [

4].

Ibrutinib is an irreversible BTK inhibitor for oral use [

5]. It covalently binds to the cysteine-481 amino acid of the BTK enzyme; thereby, preventing the migration and proliferation of malignant B-cells. However, it also decreases the lifespan of B-cells [

3]. Several studies have proven the efficacy of ibrutinib as a therapeutic agent in many NHLs, including mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), follicular lymphoma (FL), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), especially CLL [

6-

11].

Ibrutinib has a highly selective inhibitory effect towards BTK; however, it also has affinity for several kinases, such as IL2-inducible T-cell kinase, B-cell/myeloid kinase, TEC, epidermal growth factor, and Janus kinase-3 [

12]. Its effects on these kinases, apart from BTK, is responsible for several side effects [

13-

15]. Generally, ibrutinib is a well-tolerated drug with acceptable side effects [

16]. However, treatment may have to be discontinued or withdrawn in several patients due to side effects, including cytopenia, infection, bleeding, atrial fibrillation (AF), and pneumonia [

16,

17].

The major advantage of ibrutinib is that it can be used orally and has a relatively acceptable side effect profile. However, it is the preferred treatment agent in all age groups as it has a broad indication, especially in older patients who cannot tolerate cytotoxic therapy. Here, we report real-life data from 32 patients with B-cell malignancy who were treated with ibrutinib, and compare them with the data from published literature, to study the efficacy and side effect profile of ibrutinib.

Go to :

RESULTS

All the files of the 32 patients treated with ibrutinib who were followed up in our clinic between January 2017 and March 2020, were evaluated retrospectively. Of the 32 patients, 11 had CLL and 21 had other B-cell lymphomas. We examined our patients in two groups: CLL and other B-cell lymphomas, for better comparison with the other studies.

Of the 11 patients with CLL, 7 (63.4%) were male and the median age was 65 years (51–80 yr). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in

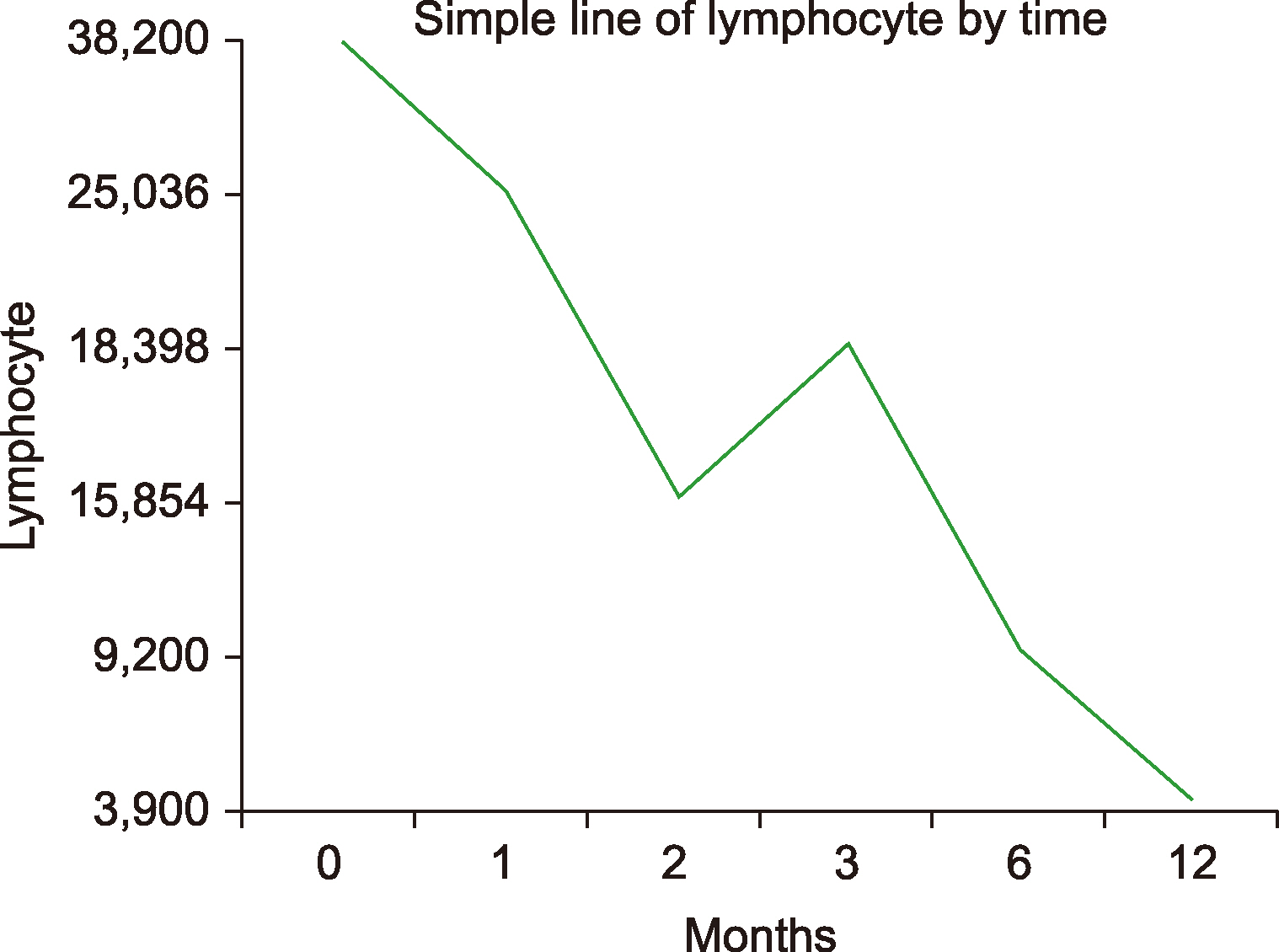

Table 1. When evaluated at the initiation of treatment with ibrutinib, only 1 patient (9.1%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score ≥3; 7 (63.6%) patients were at stage 3 or 4 under the Rai classification; 2 (18.2%) patients had bulky lesions (>10 cm). The del17p (deletion17p) mutation test was performed in all patients with CLL, and was positive in 4 (36.4%) patients. Hypertension (36.4%) was the most prevalent comorbidity in patients with CLL. Only 1 (9.1%) patient had not received any previous treatment with ibrutinib, whereas 2 (18.2%) patients received 4 or more treatment regimens. Rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide (R-FC) was the most commonly used chemotherapy protocol (63.6%). The initial dose of ibrutinib for CLL was 420 mg/day in all patients. In both groups, patients with CLL, and other B-cell lymphomas, ibrutinib was used as a single agent with no addition of other treatment agents. The patients with CLL were on ibrutinib for a median of 4 months (range, 2–18). The mean lymphocyte count at the initiation of treatment with ibrutinib decreased from 38,200×10

3/mL to 3,900×10

3/mL at the end of the 12th month of treatment. The lymphocyte counts in regard to time are shown in

Fig. 1. Treatment-emergent adverse events such as lymphocytosis had developed in 2 patients. The incidence of adverse events (grade 3 or 4) was 36.4%. Adverse events during treatment with ibrutinib are listed in

Table 2. None of the patients required dose reduction. Diarrhea (any grade) was reported in 3 (27.3%) patients, and pneumonia (any grade) occurred in 3 (27.3%) patients. Two (18.2%) patients had thrombocytopenia (any grade) and/or neutropenia. Hematological toxicity (grade≥3) was not reported in any patient. The treatment was discontinued in 4 (45.5%) patients: due to adverse events of grade 4 in 3 patients, and disease progression in 1 patient. In the final response assessment during ibrutinib treatment, the ORR was 85.6% [28.5% complete response (CR) and 57.1% partial response (PR)]. Although the median OS had not yet been reached even after ibrutinib treatment (

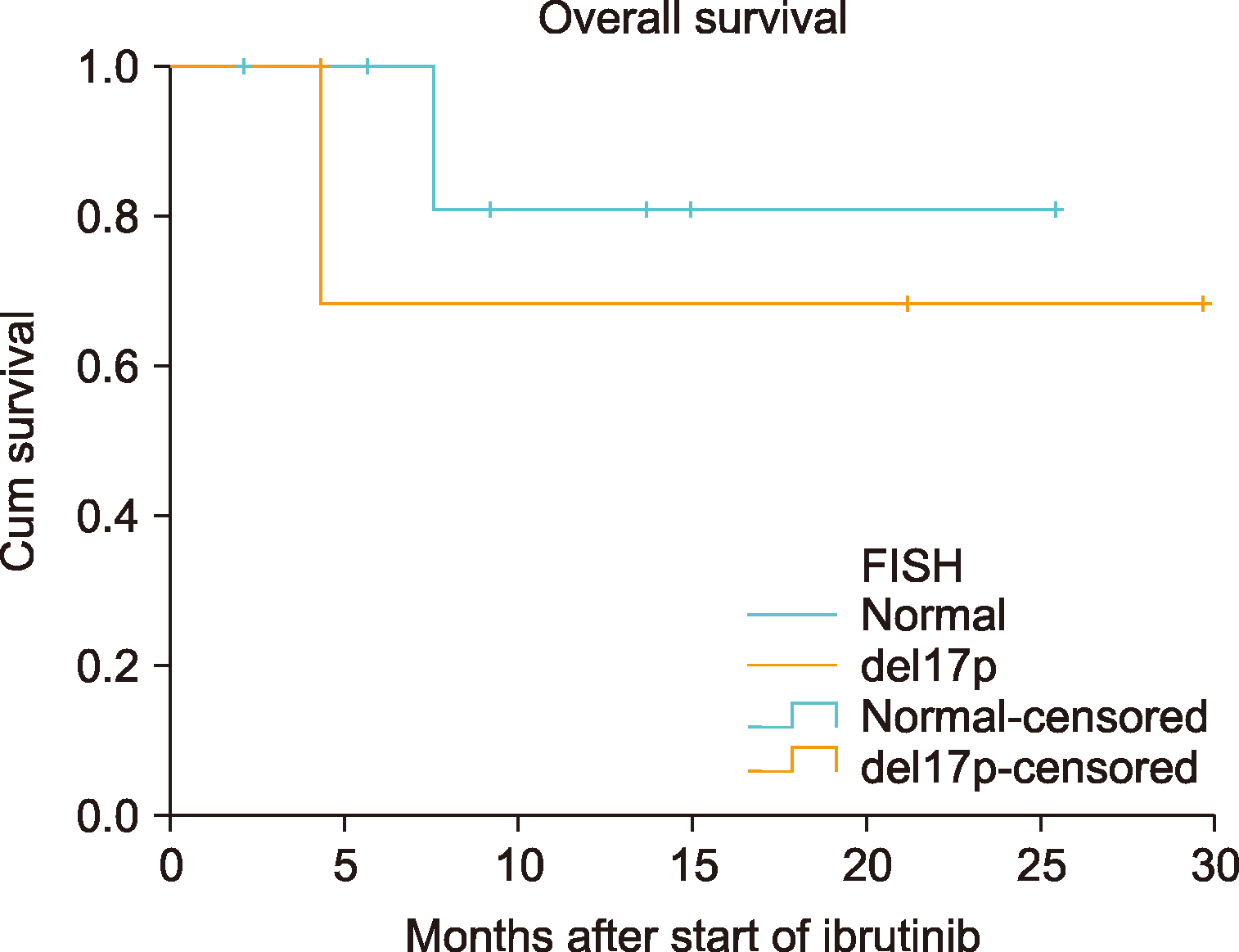

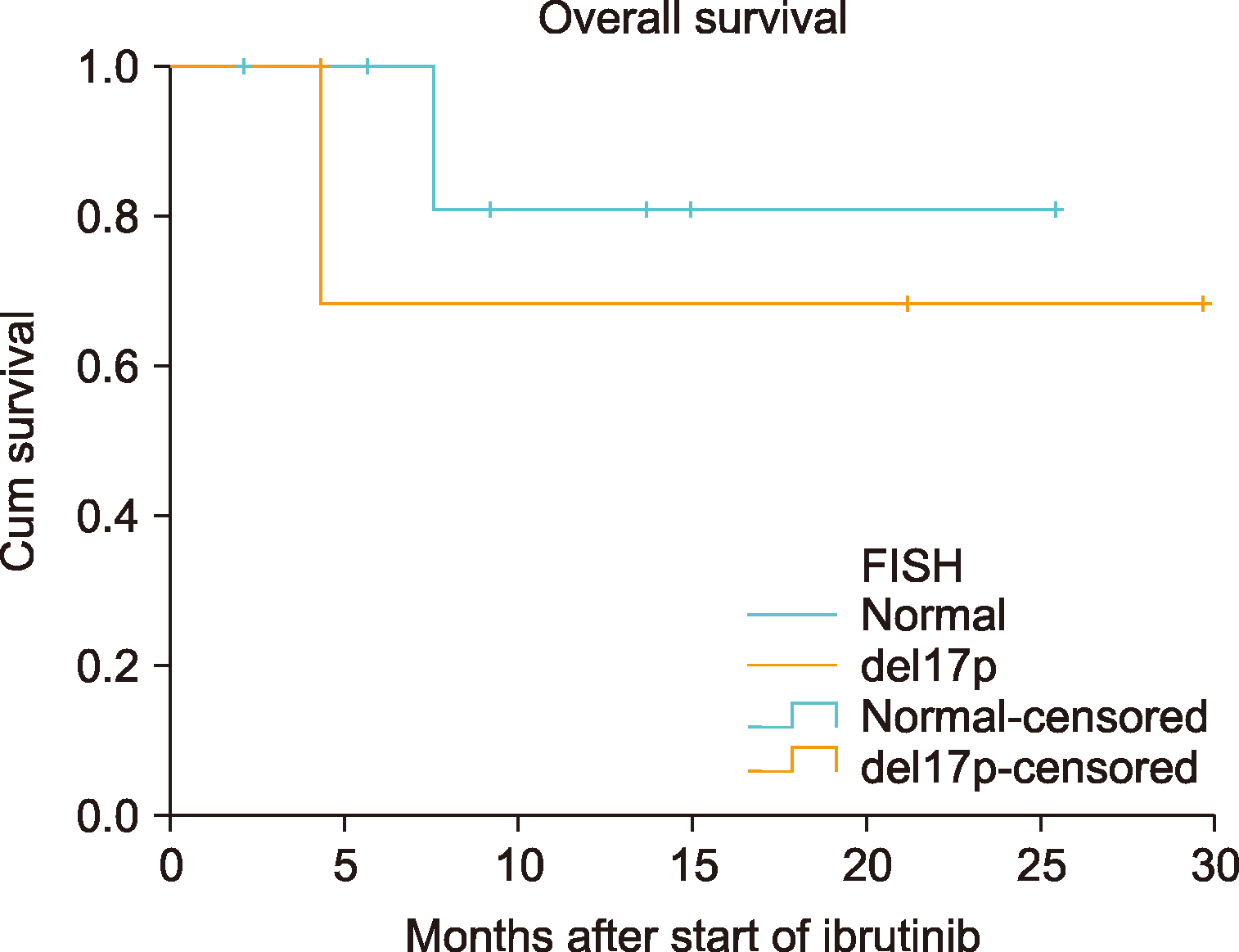

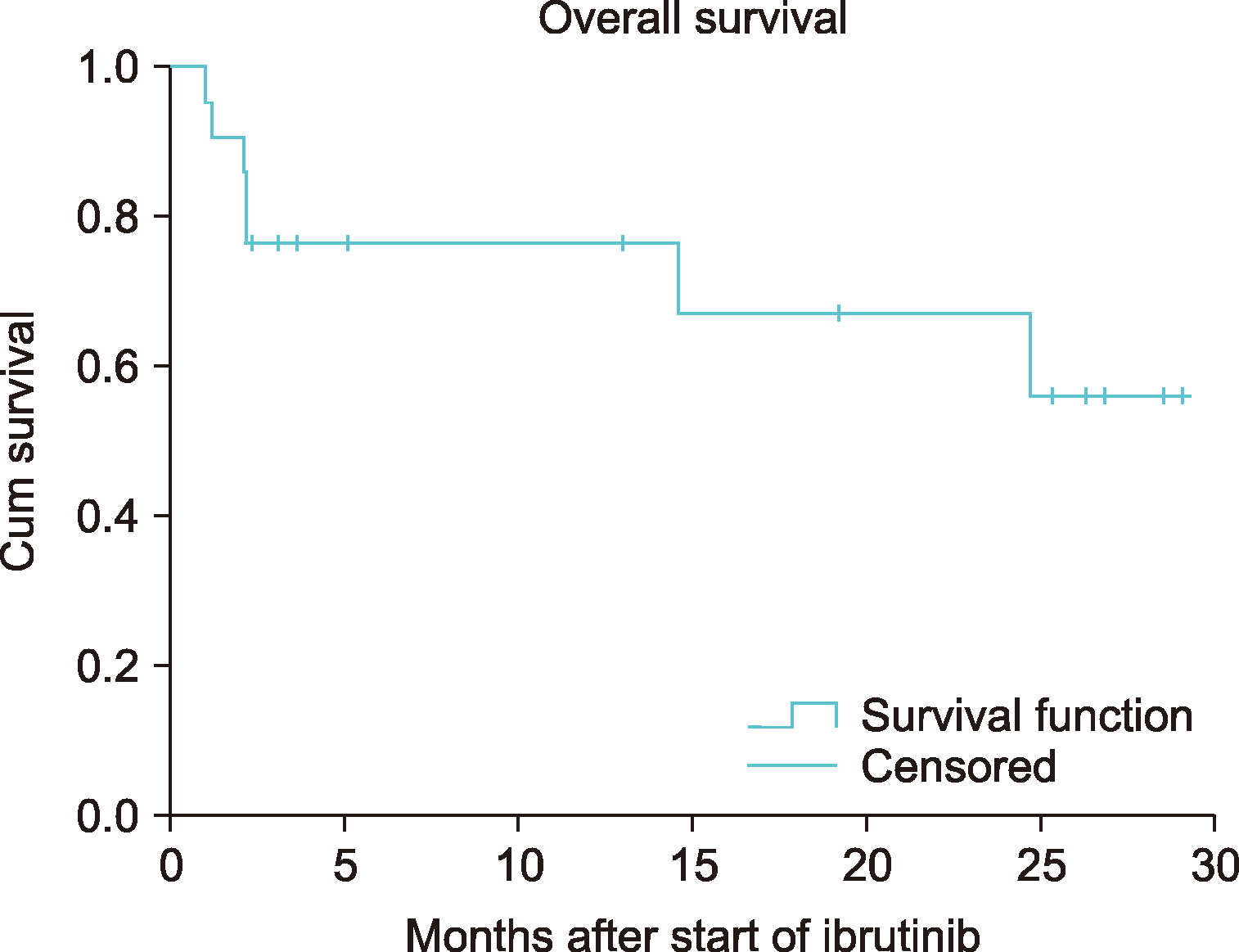

Fig. 2), the median PFS was 12.93 months [95% confidence interval (CI), 6.93–18.89].

| Fig. 1Relationship between treatment duration and lymphocyte count.

|

| Fig. 2Kaplan-Meier survival curves of overall survival based on del17p mutation in patients with CLL.

|

Table 1

Demographic and clinical features of the patients with CLL.

|

Demographic and baseline clinical features |

N=11 (%) |

|

Gender, female/male (%) |

4/7 (36.4/63.4) |

|

Age, median (range) |

65 (51–80) |

|

ECOG performance score≥3 |

1 (9.1) |

|

Bulky lesion, N (%) |

2 (18.2) |

|

Rai stage≥3, N (%) |

7 (63.6) |

|

Del17p, N (%) |

4 (36.4) |

|

N of previous treatments |

|

|

0–1 |

5 (45.5) |

|

2–3 |

4 (36.4) |

|

>3 |

2 (18.1) |

|

Previous treatment regimens |

|

|

R-FC |

7 (63.6) |

|

R-CVP |

4 (36.4) |

|

R-bendamustin |

3 (27.3) |

|

Chlorambucil |

2 (18.2) |

|

Other |

4 (36.4) |

|

Treatment duration with ibrutinib (mo, median) |

4 (2–18) |

|

Side effects of grade≥3 during treatment with ibrutinib |

4 (36.4) |

|

Treatment-emergent lymphocytosis, N (%) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Hb≤11 (g/dL), N (%) |

6 (54.5) |

|

Platelet≤100×109/L, N (%) |

7 (63.6) |

|

WBC (103/mL), mean (range) |

47,236 (1,300–182,900) |

|

Absolute lymphocyte count (103/mL), mean (range) |

38,200 (300–166,200) |

Table 2

Incidence of adverse events (AEs) in patients with CLL and NHL.

|

CLL |

NHL |

|

Hematologic AEs |

Grade 3–4, N (%) |

Any grade, N (%) |

Grade 3–4, N (%) |

Any grade, N (%) |

|

Anemia |

0 (0) |

1 (9.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

Thrombocytopenia |

0 (0) |

2 (18.1) |

1 (4.8) |

2 (9.5) |

|

Neutropenia |

0 (0) |

2 (18.1) |

1 (4.8) |

1 (4.8) |

|

Lymphocytosis |

0 (0) |

2 (18.1) |

0 (0) |

2 (9.5) |

|

Non-hematologic AEs |

|

|

|

|

|

Diarrhea |

1 (9.1) |

3 (27.3) |

2 (9.5) |

8 (38.1) |

|

Pneumonia |

3 (27.3) |

3 (27.3) |

1 (4.8) |

5 (23.8) |

|

Hemorrhage |

0 (0) |

1 (9.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

Among the 21 patients with B-cell lymphoma, 12 (57.1%) were male and their median age was 69 years (range, 53–84). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in

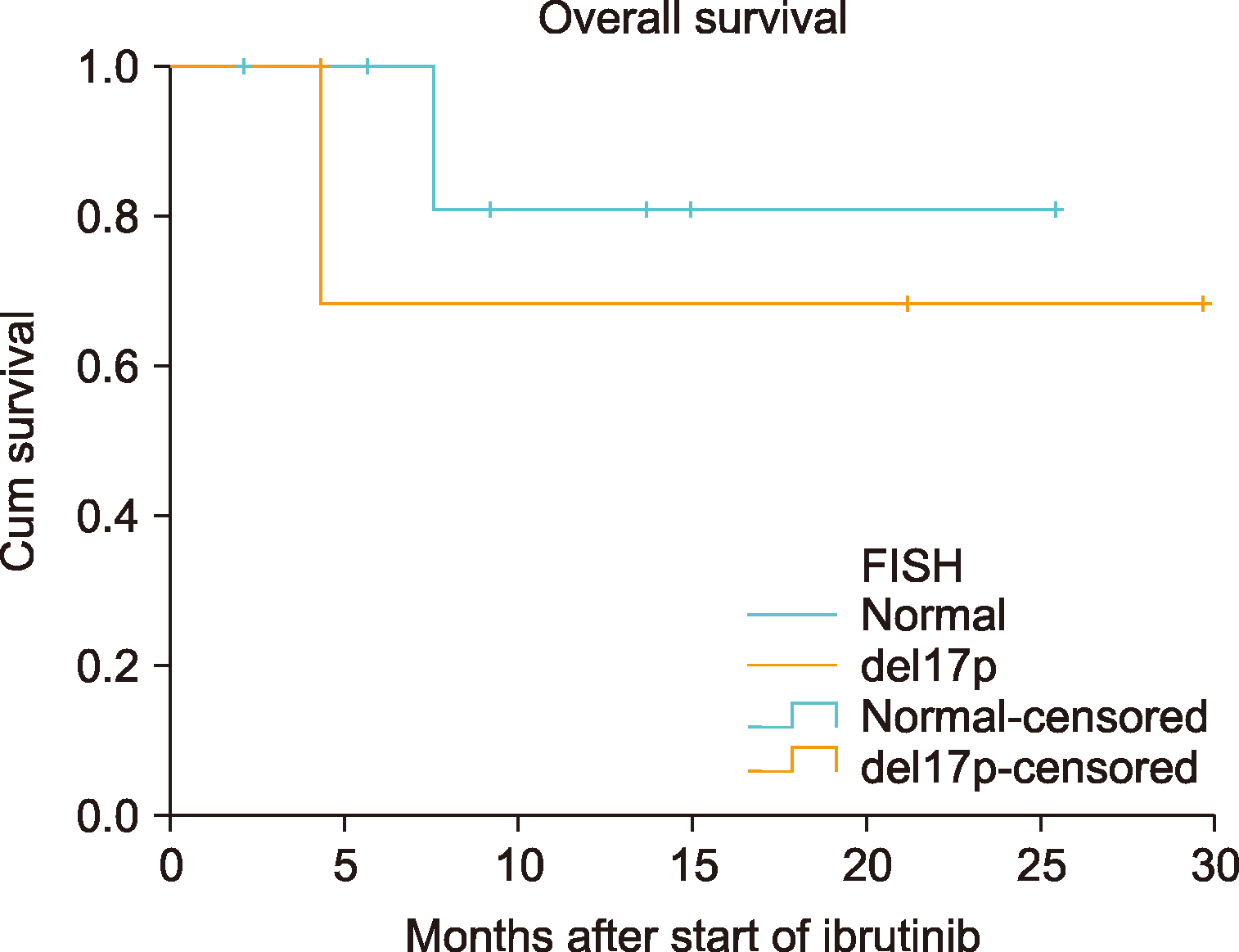

Table 3. The following number of patients received ibrutinib among the types of lymphoma and were evaluated during follow-up: 7 (33.4%) with MCL, 5 (23.8%) with DLBCL, 4 (19.0%) with MZL, 3 (14.3%) with WM, and 2 (9.5%) with FL. The outcome score [International Prognostic Index (IPI), Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI), MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI), International Prognostic Scoring System for WM (IPSSWM)] specific to the types of lymphoma, was calculated for each patient. Fourteen (66.7%) patients were in the high-risk group. The ECOG performance score was ≥3 in 8 (38.1%) patients. Four (19.0%) patients had bulky lesions (>6 cm). Twenty (95.2%) patients had advanced- stage disease (stage 3 or 4) when the treatment with ibrutinib was initiated. Ten (47.6%) of these patients had B symptoms. None of these patients had received ibrutinib as first-line therapy. Before initiating treatment with ibrutinib, 9 (42.9%) patients received one step-treatment, 9 (42.9%) patients received two step-treatment, and 3 (14.2%) patients received three steps of treatment. Autologous stem cell transplantation was performed in 1 patient (4.8%). The most commonly administered chemotherapy protocol was rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin/daunorubicin hydrochloride, oncovin (vincristine), and prednisone (R-CHOP) (95.2%). Radiotherapy was administered to 1 patient (4.8%) before the treatment. Patients with WM received 420 mg/day, and other patients received 560 mg/day of ibrutinib. The median treatment duration with ibrutinib was 4 months (range, 1–28). In the final response assessment during ibrutinib treatment, the ORR was 66.6% (20.0% CR and 46.6% PR). Two (9.5%) patients experienced treatment-emergent adverse drug event such as lymphocytosis. The most common side effect was diarrhea, noted in 8 (38.1%) patients. Pneumonia (any grade) occurred in 5 (23.8%) patients. Among the side effects that were evaluated, side effects of grade 3 or 4 were observed in 5 (23.8%) patients, and dose reduction was required in 3 (14.3%) patients. The treatment was discontinued in 2 (9.5%) patients due to side effects of grade 4, and in 1 (4.8%) patient due to disease progression. The median OS and PFS had not been reached following ibrutinib treatment (

Fig. 3).

| Fig. 3Kaplan-Meier survival curves of overall survival in patients with NHL.

|

Table 3

Demographic and clinical features of patients with NHL.

|

Demographic and baseline clinical features |

N=21 (%) |

|

Gender, female/male, N (%) |

9/12 (42.9/57.1) |

|

Age, median (range) |

69 (53–84) |

|

Types of NHL |

|

|

Mantle cell lymphoma, N (%) |

7 (33.4) |

|

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, N (%) |

5 (23.8) |

|

Marginal zone lymphoma, N (%) |

4 (19.0) |

|

Waldenström macroglobulinemia, N (%) |

3 (14.3) |

|

Follicular lymphoma, N (%) |

2 (9.5) |

|

High prognosis score, N (%) |

14 (66.7) |

|

ECOG performance score≥3, N (%) |

8 (38.1) |

|

Bulky lesion, N (%) |

4 (19.0) |

|

Ann Arbor stage≥3, N (%) |

20 (95.2) |

|

Presence of B symptoms, N (%) |

10 (47.6) |

|

N of previous treatments |

|

|

1 |

9 (42.9) |

|

2 |

9 (42.9) |

|

3 |

3 (14.2) |

|

Previous treatment regimens |

|

|

R-CHOP/CHOP |

20 (95.2) |

|

R-bortezomib/bortezomib |

5 (23.8) |

|

R-CVP/CVP |

3 (14.2) |

|

Diğer |

7 (33.4) |

|

Treatment duration with ibrutinib, median (range) |

4 (1–28) |

|

Patient requiring dose reduction, N (%) |

3 (14.3) |

|

Side effect of grade≥3 during treatment with ibrutinib |

5 (23.8) |

|

Treatment-emergent lymphocytosis, N (%) |

2 (9.5) |

|

Hb (g/dL), median (range) |

11.8 (7.6–14.6) |

|

Platelet (103/mL), median (range) |

165,000 (16,000–492,000) |

|

WBC (103/mL), median (range) |

8,400 (3,200–157,800) |

|

LDH U/L, median (range) |

257 (105–437) |

|

Creatinine clearance (mL/min/1.73 m2), median (range) |

64 (26–120) |

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Ibrutinib, the first oral BTK inhibitor is indicated for several B-cell lymphomas, especially in MCL and CLL. Among the 32 patients in this study, 11 had CLL, 7 had MCL, 5 had DLBCL, 4 had MZL, 3 had WM, and 2 had FL. Previous studies have mostly focused on the disease, whereas this study included all patients prescribed ibrutinib regardless of their diagnosis. Patients with CLL and other lymphomas were evaluated as separate groups.

CLL is more common in old age and among males [

20]. In our study, the median age was 65 years (range, 51–80), and the percentage of male patients was higher than that of the female patients. Earlier, cytotoxic agents have been used as first-line treatment for CLL, leading to serious morbidity and mortality in the elderly population [

21]. The efficacy and safety of ibrutinib have been demonstrated in several studies that included all age groups of patients with CLL who were either treatment-naive or had received multiple regimens of ibrutinib [

22,

23]. In our study, all but one patient had used ibrutinib earlier at stage 2 of the disease. In addition to ibrutinib treatment in advanced stages, the rate of del17p mutation, an indicator of poor prognosis in CLL, was 36.4% among our patients. The median treatment duration with ibrutinib was 4 months (range, 2–18); however, the ORR was 85.6% (28.5% CR and 57.1% PR) in the final response assessment. The follow-up period was not long enough; however, the treatment appeared to be very successful. Similar to the results of our study, ORR was 84% (61% PR, 20% PR-L, 3% CR) in a study with a median follow-up period of 10.2 months [

24]. A study with a longer follow-up period showed that the rate of CR and ORR increased as the treatment duration increased [

25]. As the follow-up period was not long enough in our study, the median OS had not yet been reached, and the median PFS was 12.93 months.

Ibrutinib is indicated for CLL as well as for many B-cell lymphomas [

26-

29]. Among all the patients, 95.2% of the patients were in the advanced stage (stage 3–4), and had relapsed/refractory disease. The ORR in our patients with resistant and advanced disease was 66.6% (20.0% CR and 46.6% PR). Wang

et al. [

30] found similar results in their studies on patients with refractory/relapsed MCL [ORR 68.0%, (21.0% CR and 47.0% PR)]. In other studies, the ORR was 48.0% in patients with MZL, 37.5% in patients with FL, and 90.0% in patients with WM [

28,

31,

32]. Response rate and response time in patients with FL were lower than those in patients with CLL, MCL, and MZL [

31]. However, the ORR was 82.0% in one study, in which ibrutinib was combined with rituximab in treatment-naive patients with FL [

33]. The median OS and PFS had not yet been reached because of the short follow-up period in our study.

We believe that the treatment algorithms might continue to evolve rapidly in several diseases thanks to ibrutinib treatment. The treatment can be administrated in early stages, especially in treatment-naive patients, if the efficacy of ibrutinib is clear [

21]. This is very important in fragile and older patients who cannot tolerate cytotoxic therapy [

22].

Ibrutinib is easy to use and is generally well-tolerated. However, the most common side effect is diarrhea (48–50%) [

23,

25]. In our study, the incidence of diarrhea was 27.3% in patients with CLL, and 38.1% in patients with other B-cell lymphomas. The risk of infections associated with the disease increases in CLL and other B-cell malignancies [

34]. Patients with CLL are predisposed to infections, due to hypogammaglobulinemia, dysfunction of the complement system, and impairment of neutrophil function and cellular immunity [

35]. Additionally, we believe that the administered treatments, especially cytotoxic therapy, would contribute to these situations. Infection is the most important cause of hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality in patients with CLL [

36]. For these reasons, all patients were administered trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole as a prophylactic treatment against

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, and valaciclovir was administered to prevent herpes re-infection. Besides, intravenous immunoglobulin was administered to patients with CLL, if the IgG (immunoglobulin G) level was <500. The studies that compare ibrutinib with ofatumumab and chlorambucil in terms of risk of infection (≥grade 3), showed that the risk increased minimally with no significant increase [

6,

22]. In our study, pneumonia developed in 27.3% of the patients with CLL, and 23.8% of the patients with other B-cell lymphomas. Pneumonia, disease progression, or death were the most important reasons for discontinuation or withdrawal of the treatment. It has been shown that the dose reduction of ibrutinib due to adverse events in patients with CLL, has no effect on the OS [

37]. However, it has been reported that the incidence of side effects decreases as the treatment duration with ibrutinib increases [

23]. In addition, several studies have shown that treatment with ibrutinib increases the number of T-cells and improves their functions, strengthening the immune system; however, the risk of infection is still high during the first year of treatment [

38].

Apart from infection, ibrutinib treatment is also associated with side effects, including bleeding, AF, hypertension, and arthralgia [

23]. It is shown that the risk of AF increases in patients with a history of AF and increased treatment duration with ibrutinib [

39]. In our study, no newly diagnosed cases of AF were observed. However, ibrutinib was initiated in 1 patient who was previously diagnosed with AF with controlled ventricular rate. There was no cardiac rhythm abnormalities in the patient during the treatment. We consider that, having side effects that are predictable such as HT or AF, is not a contraindication for ibrutinib treatment, if these diseases are controlled.

In addition to the above-mentioned side effects, lymphocytosis may be observed in peripheral blood due to the rapid shrinkage of the lymph nodes during ibrutinib treatment. This is temporary and is not associated with disease progression [

16]. It peaks at 2–4 weeks, and returns to normal within 6 months of treatment. Besides ibrutinib, this has also been observed during treatment with spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitors and phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors [

40,

41]. Lymphocytosis in the peripheral blood was observed in four of our patients during treatment with ibrutinib. The lymphocyte count became completely normal in the second month after continuation treatment. This picture on lymphocytosis should not be misunderstood as improvement; caution should be exercised, especially in patients with CLL.

The most important limitations of our study were that the sample size was small, and median duration of follow-up was short. However, the strength of our study was that it included patients with a wide range of diagnoses. Therefore, we were able to identify the efficacy of ibrutinib in different diagnoses in a short duration of time.

In conclusion, the real-life data from patients with different diagnoses are similar to the results of many other studies on ibrutinib. Ibrutinib is a good treatment option for CLL and other B-cell lymphomas; it has an acceptable side effect profile with high and promising CR/PR rates. Treatment with ibrutinib at an early stage decreases the burden of cytotoxic therapy in fragile patients leading to increased quality of life.

Go to :