Abstract

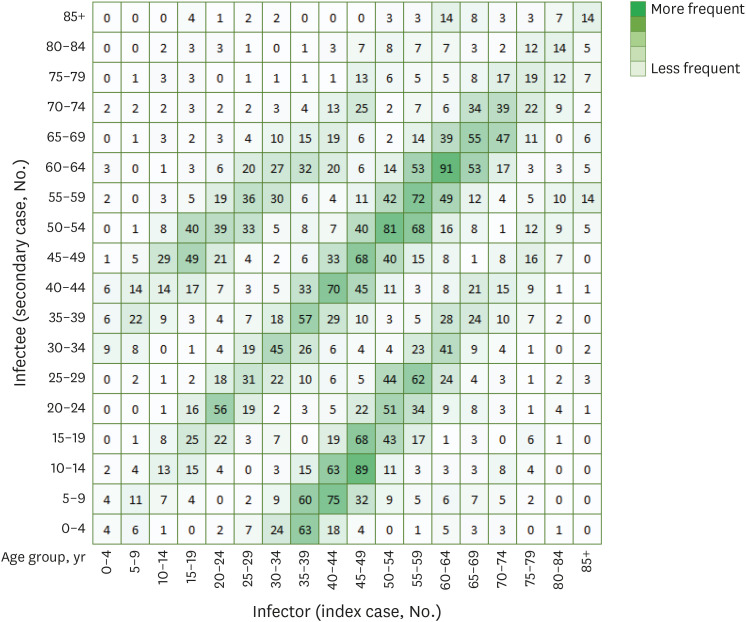

We constructed an age-to-age infection matrix to characterize the household transmission pattern of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Korea. Among 4,048 household clusters, within-age group infection dominated the overall household transmissions. Transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 was more common from adults to children than from children to adults.

Graphical Abstract

One of the main routes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) transmission is through close person-to-person contact in households.1 As COVID-19 disproportionately affects older people posing significant risk of developing severe illness, understanding of age-to-age transmission pattern in households is important for outbreak prevention and control.2 Despite the earlier success in containment of the virus, Korea is facing a third wave of COVID-19 pandemic as of December 2020.3 In aim to guide containment measures in households, we constructed an age-to-age infection matrix to characterize the transmission pattern.

Based on the Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Act, all suspected COVID-19 cases require laboratory confirmation and epidemiologic investigation. Both data are collected and stored at the National Infectious Disease Surveillance System, which includes age and address of the cases. For this study, we retrieved data on all laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases from November 20 to December 15, 2020 in Korea. Based on the address in the system, we geocoded the location of residence to capture two or more cases residing in the same x- and y-coordinates. Cases that were in the same geolocation were assumed as household clusters. The case with the earlier report was defined as infector (index case), and the case with the later report was defined as infecee (secondary case). We plotted age-to-age infection matrix to compare the age distribution pattern between infectors and infectees. In aim to exclude community clusters (i.e., hospitals), we defined 2–7 persons with the same x- and y- coordinates as a household cluster.

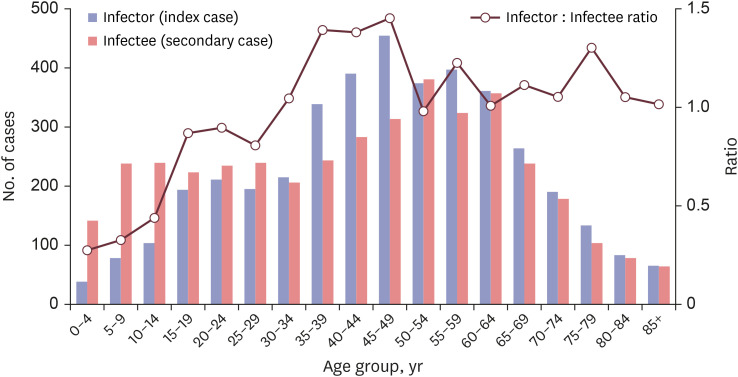

Among 14,290 laboratory confirmed COVID-19 cases, 4,048 household clusters were identified. The household transmission occurred in 21% of the cases; with one index case infecting an average of 1.57 household members. Fig. 1 shows age-to-age infection matrix with crude number and gradation by scale. In general, the infection matrix indicates that within-age group infection dominated the overall household transmissions. Infection from parents (or guardians) aged 30–49 to children aged 0–14 occurred in 455 events, whereas infection from children to parents (or guardians) occurred in 123 events. Among people aged 65 years and older (n = 734), 48.9% were infected from aged 65 years and older, while children aged 0-14 years accounted for 4.9% of the infections in this age group. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of infector (index case) and infectee (secondary case) by age groups. The highest proportion of infectors (index case) in the households were adults aged 45–49 years (391/4,088; 11.1%), followed by 55–59 years (397/4,088; 9.7%) and 40–44 years (391/4,088; 9.6%). The highest proportion of infectees (secondary case) in the households were adults aged 50–54 years (381/4,088; 9.3%), followed by 60–64 years (357/4,088; 8.7%), and 55–59 years (324/4,088; 7.9%).

There are limitations to this study. First, we did not obtain the time of onset for infector-infectee pairs, therefore the direction of transmission may be hypothetical. Second, given the low number of testing in the childhood population, the detection bias among this age group may limit the result of this study. There had been reports on transmission within daycare centers during the observed period, which may not have been ascribed in this study. Third, we have not included geographical and detection time differences for infector-infectee pairs in this study, which limits description of the result. Despite these limitations, this study quantifies the major role of age-dependency, particularly in adults, in the transmission of COVID-19 in households.4

Transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was more common from adults to children than from children to adults.5 This underscores the importance of additional awareness targeting the adult population and reappraises the implication of school closure on SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the households.

References

1. Madewell ZJ, Yang Y, Longini IM Jr, Halloran ME, Dean NE. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(12):e2031756. PMID: 33315116.

2. Li W, Zhang B, Lu J, Liu S, Chang Z, Peng C, et al. Characteristics of household transmission of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 71(8):1943–1946. PMID: 32301964.

3. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Coronavirus 2019 dashboard. Updated 2020. Accessed December 16, 2020. http://www.kdca.go.kr/cdc_eng/.

4. Kim J, Choe YJ, Lee J, Park YJ, Park O, Han MS, et al. Role of children in household transmission of COVID-19. Arch Dis Child. DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319910. Forthcoming 2020.

5. Yung CF, Kam KQ, Chong CY, Nadua KD, Li J, Tan NW, et al. Household transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from adults to children. J Pediatr. 2020; 225:249–251. PMID: 32634405.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download