1. Yoo JH. Will the third wave of coronavirus disease 2019 really come in Korea? J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(10):e110. PMID:

32174068.

2. Yoo JH. Social distancing and lessons from Sweden's lenient strategy against corona virus disease 2019. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(27):e250. PMID:

32657089.

3. Scavone C, Brusco S, Bertini M, Sportiello L, Rafaniello C, Zoccoli A, et al. Current pharmacological treatments for COVID-19: what's next? Br J Pharmacol. 2020; 177(21):4813–4824. PMID:

32329520.

4. Izda V, Jeffries MA, Sawalha AH. COVID-19: a review of therapeutic strategies and vaccine candidates. Clin Immunol. 2021; 222:108634. PMID:

33217545.

5. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - final report. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(19):1813–1826. PMID:

32445440.

8. Pollard AJ, Bijker EM. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020; 1–18. PMID:

31792373.

9. Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020; 579(7798):265–269. PMID:

32015508.

11. Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(21):1969–1973. PMID:

32227757.

12. Slaoui M, Hepburn M. Developing safe and effective Covid vaccines - operation warp speed's strategy and approach. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(18):1701–1703. PMID:

32846056.

13. Dhama K, Khan S, Tiwari R, Sircar S, Bhat S, Malik YS, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019-COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020; 33(4):e00028-20. PMID:

32580969.

14. Salvatori G, Luberto L, Maffei M, Aurisicchio L, Roscilli G, Palombo F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 SPIKE PROTEIN: an optimal immunological target for vaccines. J Transl Med. 2020; 18(1):222. PMID:

32493510.

15. Buchholz UJ, Bukreyev A, Yang L, Lamirande EW, Murphy BR, Subbarao K, et al. Contributions of the structural proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus to protective immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004; 101(26):9804–9809. PMID:

15210961.

16. Traggiai E, Becker S, Subbarao K, Kolesnikova L, Uematsu Y, Gismondo MR, et al. An efficient method to make human monoclonal antibodies from memory B cells: potent neutralization of SARS coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004; 10(8):871–875. PMID:

15247913.

17. Tai W, He L, Zhang X, Pu J, Voronin D, Jiang S, et al. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020; 17(6):613–620. PMID:

32203189.

18. Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, Liu W, Liao X, Su Y, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 71(16):2027–2034. PMID:

32221519.

19. Callow KA, Parry HF, Sergeant M, Tyrrell DA. The time course of the immune response to experimental coronavirus infection of man. Epidemiol Infect. 1990; 105(2):435–446. PMID:

2170159.

20. Cao WC, Liu W, Zhang PH, Zhang F, Richardus JH. Disappearance of antibodies to SARS-associated coronavirus after recovery. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(11):1162–1163. PMID:

17855683.

21. Wu LP, Wang NC, Chang YH, Tian XY, Na DY, Zhang LY, et al. Duration of antibody responses after severe acute respiratory syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007; 13(10):1562–1564. PMID:

18258008.

22. Choi JY, Oh JO, Ahn JY, Choi H, Kim JH, Seong H, et al. Absence of neutralizing activity in serum 1 year after successful treatment with antivirals and recovery from MERS in South Korea. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2019; 8(1):86–88. PMID:

30775355.

23. Sariol A, Perlman S. Lessons for COVID-19 immunity from other coronavirus infections. Immunity. 2020; 53(2):248–263. PMID:

32717182.

24. Bachmann MF, Mohsen MO, Zha L, Vogel M, Speiser DE. SARS-CoV-2 structural features may explain limited neutralizing-antibody responses. NPJ Vaccines. 2021; 6(1):2. PMID:

33398006.

25. Ciabattini A, Pettini E, Medaglini D. CD4(+) T cell priming as biomarker to study immune response to preventive vaccines. Front Immunol. 2013; 4:421. PMID:

24363656.

26. Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Ramirez SI, Mateus J, Dan JM, Moderbacher CR, et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020; 181(7):1489–1501.e15. PMID:

32473127.

27. Chen K, Kolls JK. T cell-mediated host immune defenses in the lung. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013; 31(1):605–633. PMID:

23516986.

28. Diao B, Wang C, Tan Y, Chen X, Liu Y, Ning L, et al. Reduction and functional exhaustion of T cells in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Front Immunol. 2020; 11:827. PMID:

32425950.

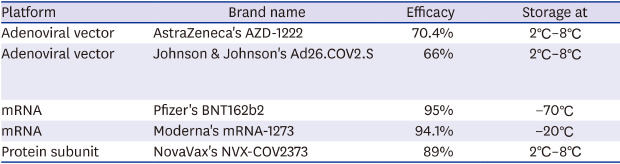

30. Mathew S, Faheem M, Hassain NA, Benslimane FM, Al Thani AA, Zaraket H, et al. Platforms exploited for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development. Vaccines (Basel). 2020; 9(1):E11. PMID:

33375677.

31. Zhang C, Zhou D. Adenoviral vector-based strategies against infectious disease and cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016; 12(8):2064–2074. PMID:

27105067.

32. Fausther-Bovendo H, Kobinger GP. Pre-existing immunity against Ad vectors: humoral, cellular, and innate response, what's important? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014; 10(10):2875–2884. PMID:

25483662.

33. Hassan AO, Kafai NM, Dmitriev IP, Fox JM, Smith BK, Harvey IB, et al. A Single-dose intranasal ChAd vaccine protects upper and lower respiratory tracts against SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2020; 183(1):169–184.e13. PMID:

32931734.

34. Ewer K, Sebastian S, Spencer AJ, Gilbert S, Hill AV, Lambe T. Chimpanzee adenoviral vectors as vaccines for outbreak pathogens. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017; 13(12):3020–3032. PMID:

29083948.

35. Guo J, Mondal M, Zhou D. Development of novel vaccine vectors: chimpanzee adenoviral vectors. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018; 14(7):1679–1685. PMID:

29300685.

36. Morris SJ, Sebastian S, Spencer AJ, Gilbert SC. Simian adenoviruses as vaccine vectors. Future Virol. 2016; 11(9):649–659. PMID:

29527232.

37. Colloca S, Barnes E, Folgori A, Ammendola V, Capone S, Cirillo A, et al. Vaccine vectors derived from a large collection of simian adenoviruses induce potent cellular immunity across multiple species. Sci Transl Med. 2012; 4(115):115ra2.

38. van Doremalen N, Lambe T, Spencer A, Belij-Rammerstorfer S, Purushotham JN, Port JR, et al. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine prevents SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2020; 586(7830):578–582. PMID:

32731258.

39. Voysey M, Clemens SA, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021; 397(10269):99–111. PMID:

33306989.

42. Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Zubkova OV, Tukhvatulin AI, Shcheblyakov DV, Dzharullaeva AS, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine in two formulations: two open, non-randomised phase 1/2 studies from Russia. Lancet. 2020; 396(10255):887–897. PMID:

32896291.

43. Mercado NB, Zahn R, Wegmann F, Loos C, Chandrashekar A, Yu J, et al. Single-shot Ad26 vaccine protects against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2020; 586(7830):583–588. PMID:

32731257.

44. Sadoff J, Le Gars M, Shukarev G, Heerwegh D, Truyers C, de Groot AM, et al. Interim results of a phase 1-2a Trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. Forthcoming. 2021; DOI:

10.1056/NEJMoa2034201.

46. Zhu FC, Li YH, Guan XH, Hou LH, Wang WJ, Li JX, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine: a dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, first-in-human trial. Lancet. 2020; 395(10240):1845–1854. PMID:

32450106.

47. Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Porter FW, Weissman D. mRNA vaccines - a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018; 17(4):261–279. PMID:

29326426.

48. Zhao L, Seth A, Wibowo N, Zhao CX, Mitter N, Yu C, et al. Nanoparticle vaccines. Vaccine. 2014; 32(3):327–337. PMID:

24295808.

49. Karikó K, Muramatsu H, Welsh FA, Ludwig J, Kato H, Akira S, et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol Ther. 2008; 16(11):1833–1840. PMID:

18797453.

50. Schlake T, Thess A, Fotin-Mleczek M, Kallen KJ. Developing mRNA-vaccine technologies. RNA Biol. 2012; 9(11):1319–1330. PMID:

23064118.

51. Anderson BR, Muramatsu H, Jha BK, Silverman RH, Weissman D, Karikó K. Nucleoside modifications in RNA limit activation of 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase and increase resistance to cleavage by RNase L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39(21):9329–9338. PMID:

21813458.

52. Zhang Z, Ohto U, Shibata T, Krayukhina E, Taoka M, Yamauchi Y, et al. Structural analysis reveals that Toll-like receptor 7 is a dual receptor for guanosine and single-stranded RNA. Immunity. 2016; 45(4):737–748. PMID:

27742543.

53. Karikó K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005; 23(2):165–175. PMID:

16111635.

54. Tanji H, Ohto U, Shibata T, Taoka M, Yamauchi Y, Isobe T, et al. Toll-like receptor 8 senses degradation products of single-stranded RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015; 22(2):109–115. PMID:

25599397.

55. Lim B, Lee K. Stability of the osmoregulated promoter-derived proP mRNA is posttranscriptionally regulated by RNase III in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2015; 197(7):1297–1305. PMID:

25645556.

56. Knights AJ, Nuber N, Thomson CW, de la Rosa O, Jäger E, Tiercy JM, et al. Modified tumour antigen-encoding mRNA facilitates the analysis of naturally occurring and vaccine-induced CD4 and CD8 T cells in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009; 58(3):325–338. PMID:

18663444.

57. Flanagan KL, Best E, Crawford NW, Giles M, Koirala A, Macartney K, et al. Progress and pitfalls in the quest for effective SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) vaccines. Front Immunol. 2020; 11:579250. PMID:

33123165.

58. Wang F, Kream RM, Stefano GB. An evidence based perspective on mRNA-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development. Med Sci Monit. 2020; 26:e924700. PMID:

32366816.

59. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(27):2603–2615. PMID:

33301246.

60. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020; NEJMoa2035389.

61. Kauffman KJ, Mir FF, Jhunjhunwala S, Kaczmarek JC, Hurtado JE, Yang JH, et al. Efficacy and immunogenicity of unmodified and pseudouridine-modified mRNA delivered systemically with lipid nanoparticles in vivo. Biomaterials. 2016; 109:78–87. PMID:

27680591.

63. Sardesai NY, Weiner DB. Electroporation delivery of DNA vaccines: prospects for success. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011; 23(3):421–429. PMID:

21530212.

64. Tebas P, Yang S, Boyer JD, Reuschel EL, Patel A, Christensen-Quick A, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of INO-4800 DNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of an open-label, phase 1 clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2020; 31:100689. PMID:

33392485.

65. Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, Li C, Hu Y, Chu K, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18-59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020; 21(2):181–192. PMID:

33217362.

66. Wang H, Zhang Y, Huang B, Deng W, Quan Y, Wang W, et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate, BBIBP-CorV, with potent protection against SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2020; 182(3):713–721.e9. PMID:

32778225.

67. Xia S, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Yang Y, Gao GF, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBIBP-CorV: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021; 21(1):39–51. PMID:

33069281.

68. Jeyanathan M, Afkhami S, Smaill F, Miller MS, Lichty BD, Xing Z. Immunological considerations for COVID-19 vaccine strategies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020; 20(10):615–632. PMID:

32887954.

69. Moore JP, Klasse PJ. COVID-19 vaccines: “warp speed” needs mind melds, not warped minds. J Virol. 2020; 94(17):e01083–20. PMID:

32591466.

70. Keech C, Albert G, Cho I, Robertson A, Reed P, Neal S, et al. Phase 1–2 trial of a SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein nanoparticle vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(24):2320–2332. PMID:

32877576.

74. Shimabukuro T, Nair N. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. JAMA. Forthcoming. 2021; DOI:

10.1001/jama.2021.0600.

76. Emergency use authorization (EUA) of The Pfizer-Biontech COVID-19 vaccine to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in individuals 16 years of age and older. Updated 2020. Accessed January 31, 2021.

https://www.fda.gov/media/144414/download.

77. Emergency use authorization (EUA) of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) In Individuals 18 years of age and older. Updated 2020. Accessed January 31, 2021.

https://www.fda.gov/media/144638/download.

78. Cabanillas B, Akdis C, Novak N. Allergic reactions to the first COVID-19 vaccine: a potential role of Polyethylene glycol? Allergy. Forthcoming. 2020; DOI:

10.1111/all.14711.

79. Ganson NJ, Povsic TJ, Sullenger BA, Alexander JH, Zelenkofske SL, Sailstad JM, et al. Pre-existing anti-polyethylene glycol antibody linked to first-exposure allergic reactions to pegnivacogin, a PEGylated RNA aptamer. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016; 137(5):1610–1613.e7. PMID:

26688515.

80. Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. Forthcoming. 2020; DOI:

10.1056/NEJMra2035343.

82. Mallapaty S, Ledford H. COVID-vaccine results are on the way - and scientists' concerns are growing. Nature. 2020; 586(7827):16–17. PMID:

32978611.

85. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Syncope after vaccination--United States, January 2005-July 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008; 57(17):457–460. PMID:

18451756.

86. Torjesen I. Covid-19: Norway investigates 23 deaths in frail elderly patients after vaccination. BMJ. 2021; 372(149):n149. PMID:

33451975.

87. Wan Y, Shang J, Sun S, Tai W, Chen J, Geng Q, et al. Molecular mechanism for antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus entry. J Virol. 2020; 94(5):e02015–9. PMID:

31826992.

88. Whitehead SS, Blaney JE, Durbin AP, Murphy BR. Prospects for a dengue virus vaccine. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007; 5(7):518–528. PMID:

17558424.

89. Lee WS, Wheatley AK, Kent SJ, DeKosky BJ. Antibody-dependent enhancement and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and therapies. Nat Microbiol. 2020; 5(10):1185–1191. PMID:

32908214.

90. Iwasaki A, Yang Y. The potential danger of suboptimal antibody responses in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020; 20(6):339–341. PMID:

32317716.

91. Hotez PJ, Corry DB, Bottazzi ME. COVID-19 vaccine design: the Janus face of immune enhancement. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020; 20(6):347–348. PMID:

32346094.

92. Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(7):1470–1477. PMID:

32255761.

93. Gudbjartsson DF, Norddahl GL, Melsted P, Gunnarsdottir K, Holm H, Eythorsson E, et al. Humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in Iceland. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(18):1724–1734. PMID:

32871063.

94. Widge AT, Rouphael NG, Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Roberts PC, Makhene M, et al. Durability of responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384(1):80–82. PMID:

33270381.

95. L'Huillier AG, Meyer B, Andrey DO, Arm-Vernez I, Baggio S, Didierlaurent A, et al. Antibody persistence in the first six months following SARS-CoV-2 infection among hospital workers: a prospective longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infect. Forthcoming. 2021; DOI:

10.1016/j.cmi.2021.01.005.

96. Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, Hastie KM, Yu ED, Faliti CE, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. Forthcoming. 2021; DOI:

10.1126/science.abf4063.

99. Wise J. Covid-19: new coronavirus variant is identified in UK. BMJ. 2020; 371:m4857. PMID:

33328153.

100. Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020; 182(4):812–827.e19. PMID:

32697968.

101. Callaway E. Could new COVID variants undermine vaccines? Labs scramble to find out. Nature. 2021; 589(7841):177–178. PMID:

33432212.

103. Weisblum Y, Schmidt F, Zhang F, DaSilva J, Poston D, Lorenzi JC, et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. eLife. 2020; 9:e61312. PMID:

33112236.

105. Dearlove B, Lewitus E, Bai H, Li Y, Reeves DB, Joyce MG, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidate would likely match all currently circulating variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020; 117(38):23652–23662. PMID:

32868447.

106. Collier DA, Meng B, Ferreira IA, Datir R, Temperton N, Elmer A, et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 Spike variant on neutralisation potency of sera from individuals vaccinated with Pfizer vaccine BNT162b2. Updated 2021. Accessed January 31, 2021.

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.19.21249840v1.

107. Kistler KE, Bedford T. Evidence for adaptive evolution in the receptor-binding domain of seasonal coronaviruses OC43 and 229E. eLife. 2021; 10:e64509. PMID:

33463525.

109. Callaway E. Fast-spreading COVID variant can elude immune responses. Nature. 2021; 589(7843):500–501. PMID:

33479534.

111. De Clercq E. Potential antivirals and antiviral strategies against SARS coronavirus infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006; 4(2):291–302. PMID:

16597209.

112. Totura AL, Bavari S. Broad-spectrum coronavirus antiviral drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2019; 14(4):397–412. PMID:

30849247.

113. Agoni C, Soliman ME. The binding of remdesivir to SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase may pave the way towards the design of potential drugs for COVID-19 treatment. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. Forthcoming. 2020; DOI:

10.2174/1389201021666201027154833.

114. Pan X, Dong L, Yang L, Chen D, Peng C. Potential drugs for the treatment of the novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) in China. Virus Res. 2020; 286:198057. PMID:

32531236.

115. Yuan S, Chan CC, Chik KK, Tsang JO, Liang R, Cao J, et al. Broad-spectrum host-based antivirals targeting the interferon and lipogenesis pathways as potential treatment options for the pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Viruses. 2020; 12(6):628.

116. Boras B, Jones RM, Anson BJ, Arenson D, Aschenbrenner L, Bakowski MA, et al. Discovery of a novel inhibitor of coronavirus 3CL protease as a clinical candidate for the potential treatment of COVID-19. Updated 2021. Accessed January 31, 2021.

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.12.293498v2.

117. Zhang WF, Stephen P, Thériault JF, Wang R, Lin SX. Novel coronavirus polymerase and nucleotidyl-transferase structures: potential to target new outbreaks. J Phys Chem Lett. 2020; 11(11):4430–4435. PMID:

32392072.

118. Slanina H, Madhugiri R, Bylapudi G, Schultheiß K, Karl N, Gulyaeva A, et al. Coronavirus replication-transcription complex: vital and selective NMPylation of a conserved site in nsp9 by the NiRAN-RdRp subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021; 118(6):e2022310118. PMID:

33472860.