INTRODUCTION

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) can be defined as “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.”

1 The purpose of developing and disseminating CPGs is to improve the quality of clinical practice and to help physicians make medical decisions.

2

To achieve this purpose, the CPG development process must meet the standards of CPGs

3 and needs to be supported and steered by a representative and consistent governing body. Among the various CPG-related institutions in Korea, the Korean Academy of Medical Sciences (KAMS) has played a major role in the development and implementation of CPGs. KAMS has conducted various activities such as CPG information center development (Korean Medical Guideline Information Center [KoMGI],

https://www.guideline.or.kr/), CPG certification program, educational programs for CPG developers, CPG manual development, and multidisciplinary CPG development through the KAMS CPG committee.

There have been several studies on the current status of what methodology was used to develop CPG and what extent was adhered to the standard methodology in Korea.

456 There are two ways to investigate the current status of CPGs: one is to conduct a survey to the medical professional society, and the other is to investigate the current status of CPGs through literature search. There may be a problem with completeness such as the method of grasping the entire status using only one of these methods. There have been several problems with the studies conducted to date, such as data collection only through literature searches.

6 data collected from limited medical professional societies,

5 or the outdated time of data collection.

456 For that reason, the KAMS CPG committee decided to investigate the current status of CPGs in Korea through survey of medical professional society memberships and literature search. The purpose of this study was to investigate the current status of the most recent clinical trial guidelines published in Korea through surveys of medical professional societies and literature searches.

METHODS

Data collection

We performed a comprehensive search in finding CPGs. Most CPGs have been published as peer-reviewed articles. Therefore, international and domestic literature databases such as MEDLINE, Embase, Google, and KoreaMed were included. Guideline databases such as the Guideline International Network and KoMGI have also been included as search resources. Examples of search terms were “Korea* AND (guideline* OR recommendation*).” The search date was April 2019.

Additionally, CPGs that were unpublished to peer-reviewed journals could exist as reports or electronic files on websites of Korean medical professional societies. For that reason, hand searching was also conducted.

Moreover, we performed a survey twice (November 2016 and November 2018) to the entire medical professional society belonging to the KAMS on the current status of CPG development. The questionnaire consisted of questions about 1) CPG development status, 2) CPG development group, 3) CPG development methodology and contents, and 4) implementation of CPGs. However, only the contents related to CPG development were analyzed.

Selection process

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) conforms to CPG definitions

7 and 2) developed within the last 5 years (since January 2014). The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) does not include recommendations, 2) nonmedical fields (dental, nursing, alternative medicine, etc.), 3) CPGs not for Koreans, and 4) if updated, previous version.

One reviewer reviewed the full text to decide whether to include/exclude, and if in doubt, the two other reviewers decided.

Data extraction and analysis

One reviewer extracted data from selected CPGs, and if in doubt, the other two reviewers extracted the data.

The data extraction form for the CPG characteristics was developed by modifying National Guideline Clearinghouse's CPG data extraction form and the development standards of the CPGs.

67 The CPG development process was divided into three phases: set-up phase, evidence review, and finalization.

89 and it was determined whether individual CPGs satisfy the standards for each phase. Standards were set according to the CPG development phase to see if the relevant content satisfies the standards 1) Set-up phase: including methodology experts, declaration of conflict of interest (COI), specification of development methodology; 2) Evidence evaluation: systematic literature search, presentation of evidence level, strength of recommendations, and consensus methodology; 3) Finalization stage: presentation of update plan, perform external review).

678

The CPG characteristics assessed were as follows:

• General CPG characteristics: publication year, funding source (public, professional societies, or industries), number of organizations that participated and 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) category of CPG topic.

• CPG characteristics for the setup phase: development methods (de novo, adaptation, or hybrid), involvement of methodologist (yes or no), and declaration of conflicts of interests (yes or no).

• CPG characteristics for the evidence review phase: systematic literature search (yes or no), system for evidence level (yes or no), system for recommendation grading (yes or no), and consensus process (formal or informal).

• Characteristic for the finalization phase: updating plan (yes or no), external review (yes or no), publication type (journal article or full version reports), and language (Korean or English).

RESULTS

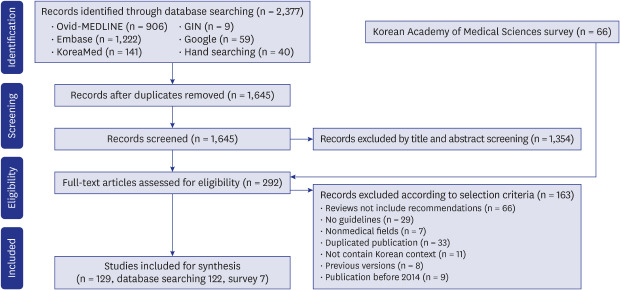

Out of 2,337 articles searched from various sources, such as literature databases and guideline databases and 66 documents collected by survey, 129 guidelines were selected (

Fig. 1 and

Supplementary Table 1). In the 2016 survey, 46 of the 166 member societies responded (response rate 27.7%), and in the 2018 survey, 53 out of 186 member societies responded (response rate 28.5%). Among them, 7 cases were conformed to the definition of CPG, and did not overlap with database searching.

Fig. 1

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of clinical practice guideline selection.

GIN = Guideline International Network.

The general characteristics of included CPGs

The general characteristics of 129 Korean CPGs are shown in

Table 1. During the recent 5 years, the yearly numbers of CPGs developed were similar around 25. A single organization was the most frequent CPG development body (42, 32.6%), followed by five or more (34, 26.4%), two (23, 17.8%), four (18, 14.0%), and three (12, 9.3%) organizations. Public (39.5%) and medical societies (39.5%) were the most common funding sources. Among the ICD-10 categories of CPG topics, “diseases of the circulatory system” (20, 15.5%) was most common, followed by “infectious diseases” (19, 14.7%) and neoplasms (14.0%).

Table 1

General characteristics of included clinical practice guidelines (n = 129)

|

Categories |

Guidelines |

|

Year of publication |

|

|

2014 |

21 (16.3) |

|

2015 |

30 (23.3) |

|

2016 |

21 (16.3) |

|

2017 |

26 (20.2) |

|

2018 |

26 (20.2) |

|

2019a

|

5 (3.9) |

|

No. of organizations in the guideline development group |

|

|

1 |

42 (32.6) |

|

2 |

23 (17.8) |

|

3 |

12 (9.3) |

|

4 |

18 (14.0) |

|

≥ 5 |

34 (26.4) |

|

Funding source |

|

|

Public |

51 (39.5) |

|

Academic |

51 (39.5) |

|

Industry sponsor |

3 (2.3) |

|

Not mentioned |

24 (18.6) |

|

Guideline topics |

|

|

Diseases of the circulatory system |

20 (15.5) |

|

Infectious diseases |

19 (14.7) |

|

Neoplasms |

18 (14.0) |

|

Diseases of the respiratory system |

15 (11.6) |

|

Endocrine diseases |

14 (10.9) |

|

Diseases of the digestive system |

12 (9.3) |

|

Mental disorders |

8 (6.2) |

|

Diseases of the skin |

3 (7.0) |

|

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system |

3 (2.3) |

|

Diseases of the genitourinary system |

3 (2.3) |

|

Injury |

3 (2.3) |

|

Diseases of the blood |

2 (1.6) |

|

Symptoms, signs |

2 (1.6) |

|

Diseases of the ear |

2 (1.6) |

|

Pregnancy, childbirth |

1 (0.8) |

|

Others |

5 (3.9) |

The characteristics of included CPGs for the setup phase

Table 2 shows the characteristics of included CPGs for the setup phase. The most common development methodologies described in the CPGs included were de novo (53, 41.1%) followed by adaptation (48, 37.2%) and hybrid (4, 3.1%). Development methods were not described in the 24 CPGs (18.6%).

Table 2

Characteristics of clinical practice guideline for the setup phase

|

Description |

Guidelines |

|

Development method |

|

|

De novo |

53 (41.1) |

|

Adaptation |

48 (37.2) |

|

Hybrid |

4 (3.1) |

|

Not mentioned |

24 (18.6) |

|

Involvement of methodologista

|

|

|

Yesb

|

65 (50.4) |

|

Noc

|

64 (49.6) |

|

Declare of COI |

|

|

Yes |

86 (66.7) |

|

Nod

|

43 (33.3) |

Among the CPGs included, about half involved methodologists (expert of systematic reviews, librarian, epidemiologist, etc., 65; 50.4%). Moreover, the authors of 86 CPGs (66.7%) declared conflicts of interest.

The characteristics of included CPGs for evidence review process

Table 3 shows the characteristics of included CPGs for the evidence review process. Systematic literature searching was performed in most guidelines (79.8%). The evidence level was reported in 104 guidelines (80.6%). The most frequently used evidence level system was the GRADE approach (44, 60.3%). Recommendation gradings were reported in 102 out of 129 (79.1%) guidelines. The most frequently used grading system was also the GRADE approach (48, 60.8%). Of the consensus methodologies used to formulate the recommendations, formal consensus methodology was most frequently used (64, 49.6%) and 34 CPGs (27.1%) used informal consensus methodologies. Thirty-one CPGs did not describe which consensus methodology was used to formulate recommendations.

Table 3

Characteristics of clinical practice guideline for evidence review phase

|

Description |

Guidelines |

|

Systematic literature searching |

|

|

Yes |

103 (79.8) |

|

No |

26 (20.2) |

|

Evidence level |

|

|

Yes |

104 (80.6) |

|

No |

25 (19.4) |

|

Recommendation grading |

|

|

Yes |

102 (79.1) |

|

No |

27 (20.9) |

|

Consensus process |

|

|

Formal |

64 (49.6) |

|

Informal |

34 (27.1) |

|

Not mentioned |

31 (23.3) |

The characteristics of included CPGs for the finalization phase

Table 4 shows the characteristics of included CPGs. Moreover, 77 guidelines (59.7%) reported an updating plan including an update period and how to update guidelines. An external review of the final draft of guidelines was performed in 76 of 129 guidelines (62.3%). The most frequent type of publication was the journal article (75.4%), and others were full-version reports (22, 18.0%). A total of 50 guidelines (41.0%) were published only in Korean, and 46 guidelines (37.7%) were published in English only, while 27% of the guidelines we assessed were published in both Korean and English.

Table 4

Characteristic for the finalization phase

|

Description |

Guidelines |

|

Updating plan |

|

|

Yes |

77 (59.7) |

|

No |

52 (40.3) |

|

External review |

|

|

Yes |

76 (62.3) |

|

No |

53 (43.4) |

|

Publication type |

|

|

Full-version reports |

22 (18.0) |

|

Journal article |

92 (75.4) |

|

Full-version and other dissemination types |

15 (12.3) |

|

Publication language |

|

|

English only |

46 (37.7) |

|

Korean only |

50 (41.0) |

|

Both English and Korean |

33 (27.0) |

DISCUSSION

We collected data on 129 CPGs developed in Korea by survey and systematic search and analyzed the general characteristics, planning process, evidence evaluation process, and finalization process.

So far, three studies in Korea investigated the current state of CPG development. Ahn and Kim

5 collected 52 CPGs and investigated their characteristics in 2012. Jo et al.

4 investigated 66 CPGs and published the results in 2013. In 2014, Choi et al.

6 researched upon 161 CPGs and published the characteristics in 2015. Since Choi et al.'s research methodology was similar to this survey, it would be appropriate to compare the data of this manuscript with the data from Choi et al.

6

In Korea, CPGs began to develop after 2000.

4 Approximately 10 CPGs have been developed annually since the mid-2000s

6 and approximately 25 CPGs have been developed annually since 2011. It seems to be necessary to look at the data for a few more years to see which temporal trends will appear in the future.

In the past, CPGs in Korea lacked a multidisciplinary nature, but these data showed significant improvement (single organization, 49.0%–32.6%; three or more organizations, 11.8%–57.3%).

6 However, there is still room for improvement because about one-third are still being developed by a single organization.

The CPG development process can be divided into three phases: setup, evidence review, and finalization.

8 The data collected for the setup phase of CPG development were the CPG development method, methodologist involvement, and declaration of COI. What was revealed in this study is that the proportion of de novo among the three development methodologies—de novo, adaptation, and hybrid—increased (20.5%–41.4%) and that the proportion of CPGs that declared COIs also increased (29.8%–66.7%). In light of this, it can be said that in CPGs developed in Korea, the proportion applying a standard methodology in the setup phase tended to increase. However, there is still room for improvement.

The data collected for the evidence evaluation phase were systematic searching, evidence levels, recommendation gradings, and consensus methods. It was revealed that the proportion of systematic searching (54.6%–79.8%), evidence levels (64.5%–80.6%), and recommendation gradings (68.3%–79.1%) increased. Considering this, it can be said that the rate of utilizing systematic reviews in the evidence evaluation phase has increased in the CPG development, which is encouraging. However, it is not clear whether quantitative growth as well as qualitative growth occurred because the investigation was not conducted for search details, evidence levels, and recommendation gradings.

The data collected for the finalization phase were updating plan, external review, publication type, and publication language. It is encouraging that the proportion of CPGs describing updating plans has increased (36.0%–59.7%). However, the fact that 41% of Korean CPGs have not been reviewed externally requires improvement. The fact that 37.7% of CPGs included were published in English only requires improvement given that most of the readers are Korean.

This study has several strengths. First, as a method of collecting data of the current status of CPG in Korea, the comprehensiveness was enhanced by medical societies survey, which served to complement the literature searches. Second, authors who selected CPGs based on inclusion/exclusion criteria and extracted appropriate data were experienced CPG development experts. Third, it is possible that data acquisition was more complete because it was implemented by KAMS, the most authoritative organization for CPG development in Korea.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the survey contents were mainly quantitative and did not cover qualitative contents. Since COI, the evidence level, and the development method require detailed evaluation, it is necessary to look into qualitative contents through additional research. Second, the current CPG status in Korea was compared with that of Choi et al.'s

6 reports.

7 However, there were some data that could not be compared because the survey contents were not completely consistent. Third, there is a possibility that there are some CPGs in Korea that are not included because the literature search or medical society survey was not perfect.

In conclusion, when examining the characteristics of CPGs developed in Korea in the last 5 years, the proportion of meeting CPG development standards has increased compared to that in the past, but there are still many areas for improvement.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download