Graphical Abstract

By November 2020, approximately 50 million people around the world were confirmed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, including 1.2 million deaths from COVID-19 related diseases (2.5%).1 The Korean government designated COVID-19 infection as the first class infectious disease, and has been striving to reduce the caseload with quarantine activities, including maintenance of social distance and mask-wearing.2 However, the risk of sporadic regional infections has increased and secondary outbreaks are ongoing, even though medical resources are limited. Many people are currently infected through contact regardless of age limit. Although no child has died from COVID-19 infections in Korea until now, high-risk groups of COVID-19 were mostly prohibited from visiting neonatal intensive care units (NICU). As a result, face-to-face time between neonates and parents has significantly decreased compared to interactions before COVID-19 pandemic declaration.3 Parents’ anxiety and complaints against the ban of personal visits have increased. In addition, challenges involving the early stages of birth such as decreased breastfeeding and restricted attachment between parents and neonates have emerged. Most of the medical personnel maintain telephone calls to inform parents of the baby's condition with pictures of babies taken on mobile phones; however, such efforts are not adequate to resolve the aforementioned problems.

During the post-COVID-19 era, methods other than direct contact have been suggested in various medical areas.45678 In particular, video interview has been introduced for the palliative care of oncology patients and for the treatment of patients in rural areas or prisons.910 The implementation of video interaction with adults in the COVID-19 pandemic era was highly satisfactory in the previous study.11 We concluded that a video interview in NICU is feasible. Therefore, video interviews were commenced at the NICU of Jeonbuk National University Hospital (JBNUH) from May 2020 given the limited scope for in-person visits to prevent COVID-19 infection.

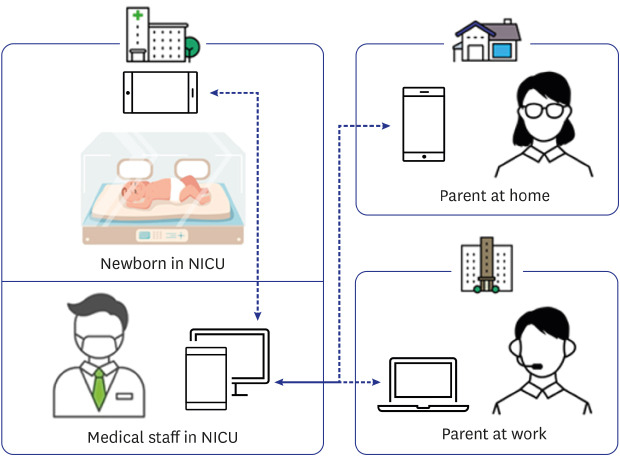

The video interview in NICU was planned to connect the medical staffs, neonates, and parents simultaneously. The method of participation in the face-to-face video interview was uploaded to Youtube® (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Fn64caknU4) so that parents can access the program according to the instructions. Parents were asked to participate in the video interview at the scheduled time. We bought a cell phone equipped with two cameras and ZOOM Cloud Meetings® application. A single cell phone was reserved for the neonate and another for the medical staff during the real-time video interview. Simply, ZOOM Cloud Meeting application on a computer in the NICU was the host and the two cell phones were added as clients. Guardian training for video interview was replaced by Youtube® and equipped with handy cell phones, which provided adequate time for a nurse and a single medical staff to prepare for a visit in about 10 minutes. However, additional medical personnel were needed to adjust the time for appointment with parents (Fig. 1).

The video interview began by connecting the medical staff, patients, and the baby. The total video interview time was up to 20 minutes per patient, including 15 minutes of consultation with medical staff and the parent with baby on the screen, and 5 minutes of additional time only for the baby and parents without the doctor. During consultation, the medical staff looked at the baby's screen and at the same time explained the baby's general condition, management plan, and consent form to parents. Of course, they were allowed to ask questions of the medical staff through the screen while looking at the baby's face. Parents were allowed to visit their doctor in person if they wanted a more detailed explanation or needed a doctor's interview, after which, the medical staff of NICU photographed the baby for the parents.

Face-to-face video interviews were reserved in advance by section at the request of parents. The video interview in NICU was conducted for up to three families per day, and lasted a total of 70 minutes per day, including 10 minutes for equipment setting. Two medical staff members were required for video interview preparation, one for equipment installation and another for patient description. Sometimes, it was difficult to conduct the video interview. If the patient-reserved video interview was unstable or occurred in the middle of medical procedure, the video interview had to be canceled. In addition, the video interview was postponed if there were other patients in the emergency ward and it was hard for the medical staff to prepare the video interview.

The advantages and disadvantages of months of running NICU face-to-face video interview are as follows. Overall, most of the parents were satisfied with video interview in the NICU of JBNUH. The parents saw their baby in real time regardless of the baby's condition and unrestricted by location, which saved time spent in travel. Even if mom and dad were in different locations, the face-to-face video allowed visitation from the comfort of home or anywhere that parents have access and families other than parents can also participate. In particular, mothers of neonates transferred from outside were more satisfied because they were separated from their babies right after birth and had difficulty traveling. Also, parents were able to see the medical staff face-to-face, which improved the relationship between the staff when compared with just a telephone call. The disadvantages for parents were that they were not allowed to visit other than during the scheduled times, and that there was a time limit. Considering the time to prepare for the video interview, the total number of video interviews was limited to 3 infants per day, but the parents wanted to visit more often. The parents also complained that they cannot see or touch the baby directly and can only meet through the screen. Therefore, we need to find a rational point between the probability of infection and stability of baby via kangaroo care. If the evidence for protection from COVID-19 is established in the future, direct contact, such as breast feeding and/or kangaroo care may be carefully considered. In addition, some parents reported difficulty using the application and others with financial difficulty had a limited access to a cell phone.

According to the medical staff, most of all, the video interview minimized direct contact to prevent COVID-19 infection, thereby reducing the infection. Because most of the neonates are in the incubator, it was not difficult to organize the video interview in NICU, and the cost of equipment to operate the video interview was affordable. However, the role of medical staff preparing for the video interview including reservation, prior contact with parents, and equipment preparation has increased. However, the biggest concern about the video interview was protection of patient information. It is necessary to consider the privacy and security risks associated with a video interview, and the need for physical examination in telemedicine and/or telehealth.1213 Since the standards for video interview have yet to be set in Korea, efforts to legislate protection of patient information are needed.

Six months of experience suggested that it was not difficult to realize the video interview in NICU. Despite the increasing workload of the medical staff, a dedicated face-to-face video interview designed to resolve the aforementioned challenges is expected to become more active. We have a plan to evaluate the satisfaction of parents and staffs, and additional goals in a further study.

If the method for video interview in NICU is established and widely shared, it will represent an alternative option to visit neonates during the COVID19 outbreak.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our sincere appreciation of all NICU members and Dr. Yum who took care of the babies with great love.

References

1. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease-19, Republic of Korea as of September 15, 2020. Updated 2020. Accessed September 15, 2020. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/.

2. National Law Information Center. Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act. No. 17067, Article 2. Mar. 04, 2020. Updated 2020. Accessed November 24, 2020. https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?query=INFECTIOUS+DISEASE+CONTROL+AND+PREVENTION+ACT#liBgcolor5.

3. Darcy Mahoney A, White RD, Velasquez A, Barrett TS, Clark RH, Ahmad KA. Impact of restrictions on parental presence in neonatal intensive care units related to coronavirus disease 2019. J Perinatol. 2020; 40(Suppl 1):36–46. PMID: 32859963.

4. Mahajan V, Singh T, Azad C. Using telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Pediatr. 2020; 57(7):652–657.

5. Aziz A, Zork N, Aubey JJ, Baptiste CD, D'Alton ME, Emeruwa UN, et al. Telehealth for high-risk pregnancies in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Perinatol. 2020; 37(8):800–808. PMID: 32396948.

6. Loeb AE, Rao SS, Ficke JR, Morris CD, Riley LH 3rd, Levin AS. Departmental xperience and lessons learned with accelerated introduction of telemedicine during the COVID-19 crisis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020; 28(11):e469–76. PMID: 32301818.

7. Contreras CM, Metzger GA, Beane JD, Dedhia PH, Ejaz A, Pawlik TM. Telemedicine: atient-provider clinical engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020; 24(7):1692–1697. PMID: 32385614.

8. Yum HK. Suggestions to repare for the second epidemic of COVID-19 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(19):e191. PMID: 32419402.

9. Tasneem S, Kim A, Bagheri A, Lebret J. Telemedicine video visits for patients receiving palliative care: a qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019; 36(9):789–794. PMID: 31064195.

10. Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, Deming P, Kalishman S, Dion D, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364(23):2199–2207. PMID: 21631316.

11. Ramaswamy A, Yu M, Drangsholt S, Ng E, Culligan PJ, Schlegel PN, et al. Patient satisfaction with telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2020; 22(9):e20786. PMID: 32810841.

12. Hall JL, McGraw D. For telehealth to succeed, privacy and security risks must be identified and addressed. Health Aff. 2014; 33(2):216–221.

13. Cotet AM, Benjamin DK. Medical regulation and health outcomes: the effect of the physician examination requirement. Health Econ. 2013; 22(4):393–409. PMID: 22450959.

Fig. 1

This picture is a schematic diagram of video interview conducted in the NICU. The medical staff needs two cell phones and/or computer, and parents need only a cell phone or a computer. A cell phone or computer in the NICU hosts the conference using ZOOM and uses a cell phone with newborn and parents at home or work. Thus, the video interview allows patients and medical staff to watch patients simultaneously.

NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download