This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has rapidly spread worldwide, there are growing concerns about patients' mental health. We investigated psychological problems in COVID-19 patients assessed with self-reported questionnaires including the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale, and Impact of Event Scale-Revised Korean version. Ten patients who recovered from COVID-19 pneumonia without complications underwent self-reported questionnaires about 1 month after discharge. Of them, 10% reported depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) while 50% had depression during the treatment. Perceived stigma and history of psychiatric treatment affected PTSD symptom severity, consistent with previous emerging infectious diseases. Survivors also reported that they were concerned about infecting others and being discriminated and that they chose to avoid others after discharge. Further support and strategy to minimize their psychosocial difficulties after discharge should be considered.

Go to :

Graphical Abstract

Go to :

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Depression, PTSD, Survivor, Pneumonia

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has rapidly spread worldwide

1; accordingly, there are growing concerns in various fields about COVID-19 patients' mental health. Patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) have been shown to experience psychological distress after cure as well as during their illness; in 2003, while 35% SARS survivors in Hong Kong reported significant anxiety and/or depressive symptoms at four weeks or more after discharge,

2 43% of the MERS survivors had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 27% had depression at 12 months after the outbreak.

3 COVID-19, as a new type of emerging infectious disease (EID), shows different characteristics when compared with past EIDs, like high infectivity, prevalence, and public impact.

1 However, knowledge on COVID-19 patients' psychological distress after cure remains meager; thus, we retrospectively investigated the psychological problems in COVID-19 patients about 1 month after discharge from hospital.

We searched for all patients who were confirmed to have experienced a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection through reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction using respiratory specimen, and who received isolation treatment in the nationally designated high-level isolation unit in Seoul National University Bundang Hospital from January to 31 May 2020. Among these, we reviewed patients who responded to the following self-reported questionnaires to evaluate their depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms: the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),

4 Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale,

5 and Impact of Event Scale-Revised Korean version (IES-R-K),

6 respectively. The patients we reviewed also responded to an 8-item tool that was used in a previous study for MERS survivors,

3 and that was utilized at this time to assess perceived stigma regarding COVID-19. This perceived stigma questionnaire was adopted from the 40-item human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) stigma scale, which was developed by Berger et al.

7 and the 8-item short version of the HIV stigma scale.

8 Responses were rated on a 4-point Likert scale, where higher scores meant higher levels of perceived stigma; we defined a high level of perceived stigma as any score that was two standard deviations from the mean. To compare mental health outcomes according to the sociodemographic characteristics and clinical features, we applied the Mann-Whitney U test with the significance set at

P < 0.05.

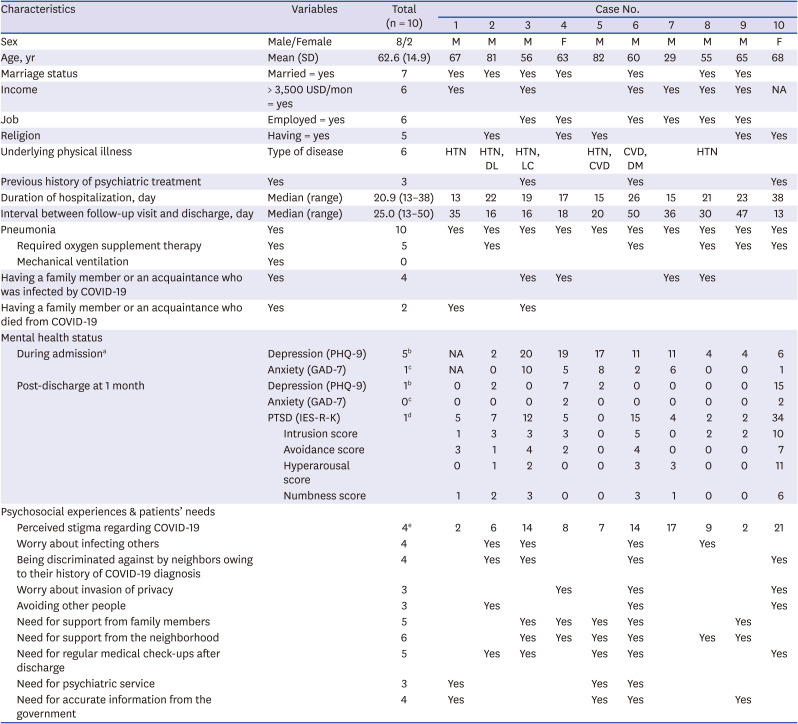

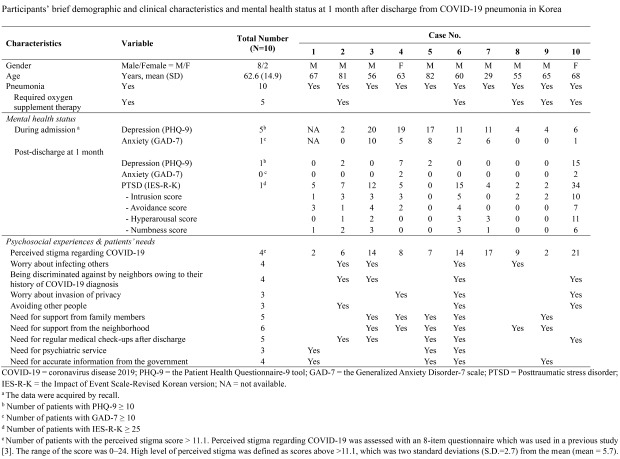

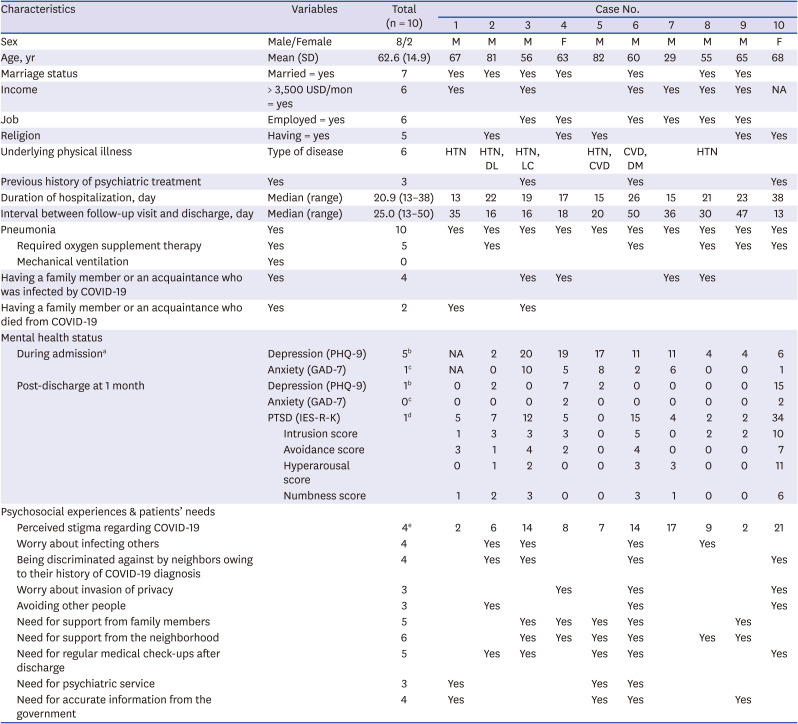

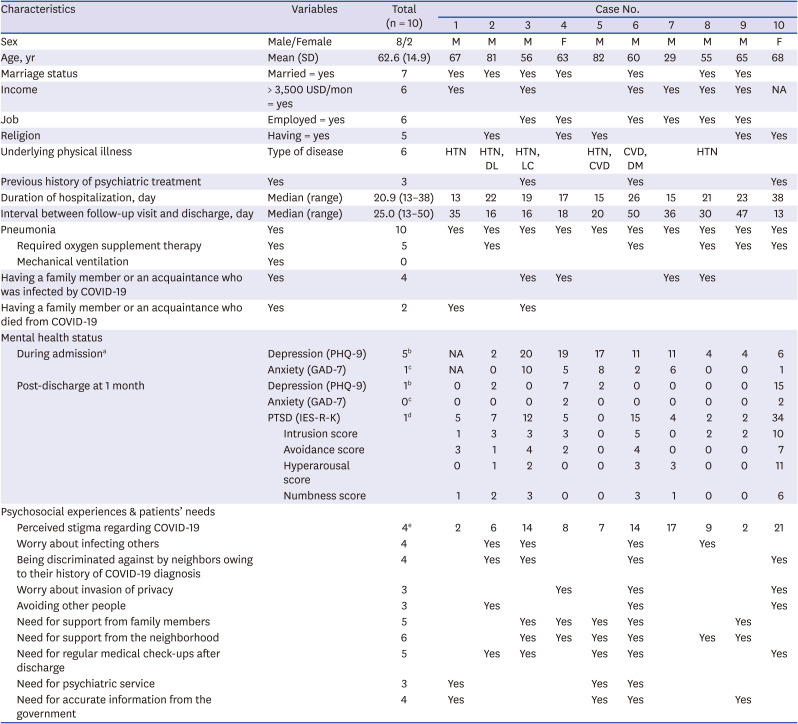

Ten patients completed the self-reported questionnaires, and this was done about 1 month after discharge. Descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 1. All patients were diagnosed with pneumonia through radiologic examination (i.e., chest and/or chest computed tomography [CT]); additionally, five patients required oxygen supplement therapy during hospitalization. The median duration of isolation treatment was 20 days (range, 18–38 days). All patients successfully recovered from COVID-19 pneumonia without complications or sequelae in the lung; this was assessed using chest CT ± pulmonary function test. One month after discharge, all patients visited the hospital for a follow-up consultation (median, 25 days; range, 13–50 days).

Table 1

Participants' demographic and clinical characteristics and mental health status at 1 month after discharge from COVID-19 pneumonia in Korea

|

Characteristics |

Variables |

Total (n = 10) |

Case No. |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

Sex |

Male/Female |

8/2 |

M |

M |

M |

F |

M |

M |

M |

M |

M |

F |

|

Age, yr |

Mean (SD) |

62.6 (14.9) |

67 |

81 |

56 |

63 |

82 |

60 |

29 |

55 |

65 |

68 |

|

Marriage status |

Married = yes |

7 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Income |

> 3,500 USD/mon = yes |

6 |

Yes |

|

Yes |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

NA |

|

Job |

Employed = yes |

6 |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Religion |

Having = yes |

5 |

|

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

Underlying physical illness |

Type of disease |

6 |

HTN |

HTN, DL |

HTN, LC |

|

HTN, CVD |

CVD, DM |

|

HTN |

|

|

|

Previous history of psychiatric treatment |

Yes |

3 |

|

|

Yes |

|

|

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

Duration of hospitalization, day |

Median (range) |

20.9 (13–38) |

13 |

22 |

19 |

17 |

15 |

26 |

15 |

21 |

23 |

38 |

|

Interval between follow-up visit and discharge, day |

Median (range) |

25.0 (13–50) |

35 |

16 |

16 |

18 |

20 |

50 |

36 |

30 |

47 |

13 |

|

Pneumonia |

Yes |

10 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Required oxygen supplement therapy |

Yes |

5 |

|

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Mechanical ventilation |

Yes |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Having a family member or an acquaintance who was infected by COVID-19 |

Yes |

4 |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

|

Having a family member or an acquaintance who died from COVID-19 |

Yes |

2 |

Yes |

|

Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mental health status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

During admissiona

|

Depression (PHQ-9) |

5b

|

NA |

2 |

20 |

19 |

17 |

11 |

11 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

|

Anxiety (GAD-7) |

1c

|

NA |

0 |

10 |

5 |

8 |

2 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Post-discharge at 1 month |

Depression (PHQ-9) |

1b

|

0 |

2 |

0 |

7 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

|

Anxiety (GAD-7) |

0c

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

PTSD (IES-R-K) |

1d

|

5 |

7 |

12 |

5 |

0 |

15 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

34 |

|

Intrusion score |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

|

Avoidance score |

3 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

|

Hyperarousal score |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

|

Numbness score |

1 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

Psychosocial experiences & patients’ needs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perceived stigma regarding COVID-19 |

|

4e

|

2 |

6 |

14 |

8 |

7 |

14 |

17 |

9 |

2 |

21 |

|

Worry about infecting others |

|

4 |

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Yes |

|

Yes |

|

|

|

Being discriminated against by neighbors owing to their history of COVID-19 diagnosis |

|

4 |

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

Worry about invasion of privacy |

|

3 |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

Avoiding other people |

|

3 |

|

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

Need for support from family members |

|

5 |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Yes |

|

|

Need for support from the neighborhood |

|

6 |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Need for regular medical check-ups after discharge |

|

5 |

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

Need for psychiatric service |

|

3 |

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

Need for accurate information from the government |

|

4 |

Yes |

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Yes |

|

Among the survivors, at 1 month post-discharge, 10% reported depression (i.e., PHQ-9 ≥ 10) and PTSD (IES-R-K ≥ 25); additionally, 50% reported depression during the treatment. No significant anxiety scores were observed after discharge. Interestingly, patients with high perceived stigma (n = 4) tended to have higher scores for PTSD symptoms (their IES-R-K mean score = 16.3 vs. 3.5 in patients with low perceived stigma; P = 0.067), especially in the hyperarousal (mean score = 4.8 vs. 0.2, P = 0.010) and numbness (mean score = 3.3 vs. 0.5, P = 0.019) domains. Survivors with a previous history of psychiatric treatment (n = 3) also had higher scores for PTSD symptoms (mean score = 20.3 vs. 3.6 in patients without a previous history of psychiatric treatment, P = 0.017); still, they did not show scores for depression and anxiety that differed significantly from survivors without such a history. There were no significant differences in the scores for depression, anxiety, or PTSD by pneumonia severity and whether their tracing routes were disclosed to the public. Notwithstanding, 40% of the survivors worried about infecting others and being discriminated against by neighbors owing to their history of COVID-19. They wanted to receive support from neighbors (60%), from their families (50%), and to undergo regular hospital check-ups after discharge (50%). Moreover, they needed accurate information from the government (40%) and access to psychiatric service (30%).

Our results indicated that survivors who get completely cured of COVID-19 pneumonia, without experiencing significant complications, may be at low risk for post-discharge depression or anxiety; still, they could develop or express depressive symptoms/depression during treatment. Moreover, our findings suggested that perceived stigma regarding COVID-19 and a previous history of psychiatric treatment may affect the severity of PTSD symptoms; these were consistent with the highlights from a past study on MERS survivors, which was conducted in Korea in 2015.

3 In 2015, Korea experienced an outbreak of MERS, and a study on survivors from this period showed that they experienced discrimination; specifically, people regarded them as perpetrators of the infection, even after being cured.

9 Moreover, previous studies on SARS survivors in Hong Kong also remarked that they suffered from SARS-associated stigma after they returned to their community and it did not decrease over time.

1011 Perceived stigma that may be reshaped by survivors' experiences in their community after discharge, for example, being discriminated against by neighbors could modify their response to—the potentially traumatic COVID-19 situation. Thus, although COVID-19 patients in our sample seemed to be able to recover from depression if they experienced physical improvements, dealing with their PTSD symptoms may prove more complicated; these symptoms depend on the attitudes of the community/society toward the survivors along the course of the pandemic, and they can persist for a long time if the attitudes are negative. Our findings also suggested that survivors could have been experiencing psychosocial difficulties after discharge, namely, when they interacted with other people. Some survivors still worried about infecting others as a perpetrator and exposure of their privacy that may be a source of being blamed by people regarding COVID-19 infection, which may lead to social avoidance.

This research presented only the preliminary results of an assessment of the mental health status post-infection of a small sample of people who were diagnosed with COVID-19 pneumonia, were subsequently cured, and who did not need ventilator treatment—namely, did not incur in major complications. Accordingly, studies with larger samples and that also include patients who received intensive care are warranted.

Nevertheless, we could infer from our results that some of the survivors might have experienced mental health problems according to their psychiatric history or their perception of COVID-19 associated stigma and could have incurred in psychosocial difficulties after discharge, especially in worry about discrimination. Thus, to enhance the psychosocial recovery of patients after COVID-19, stakeholders should utilize strategies aimed at managing their mental health and facilitating their reintegration into the community.

Ethics Statement

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital approved the study (IRB No. B-2006-618-104). The IRB waived the requirement for informed consent.

Go to :