INTRODUCTION

The global burden of infertility is rising and accessibility to infertility treatments and assisted reproduction is a challenging issue.

123 In addition, the burden is increased with mental illness including depression and anxiety.

4 To address the burden of infertility for efficient planning by the fertility healthcare system, it is necessary to assess the problem.

In Korea, the total fertility rate is the lowest among the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries in 2017, with 1.1 births per couple.

5 The most explainable reason for this low birth rate is economic recession and increasing cost for raising a child.

6 Moreover, other factors such as rising women's status and their achievement in the workplace are also related to low birth rate.

7 However, the increased rate for infertility might be also attributable to this phenomenon. According to recent national health statistics, a total number of about 220,300 people were diagnosed at an infertility clinic and a total number of 52,860 in vitro fertilizations were performed in 2016. However, until September 2017, Korean National Health Insurance (NHI) only provided limited coverage for infertility tests and surgery for underlying medical conditions associated with secondary infertility. In other words, the NHI does not generally cover the in-vitro fertilization (IVF) and medical costs. In fact, the large portion of medical cost for fertilization is from repetitive IVF and related tests. Thus, according to another national report in 2003, 26.6% of infertile couples had a plan to stop IVF due to financial crisis.

8

In order to improve the financial barriers to fertilization procedures, the government started to provide subsidies to low-income couples whose monthly income was under 130% of average since 2006. In 2009, the subsidy for low-income couples was expanded from two to three IVF procedures. Until 2017, they also provided similar support to middle or high income couples. Recently, they started to provide insurance coverage for infertility procedures for people who were diagnosed infertile from October, 2017. Even though the government tries to improve financial accessibility, the economic barriers are higher for the low-income population. However, there has not been concrete research whether these kinds of polices decreased the gap in outcomes among infertility patients across socioeconomic status.

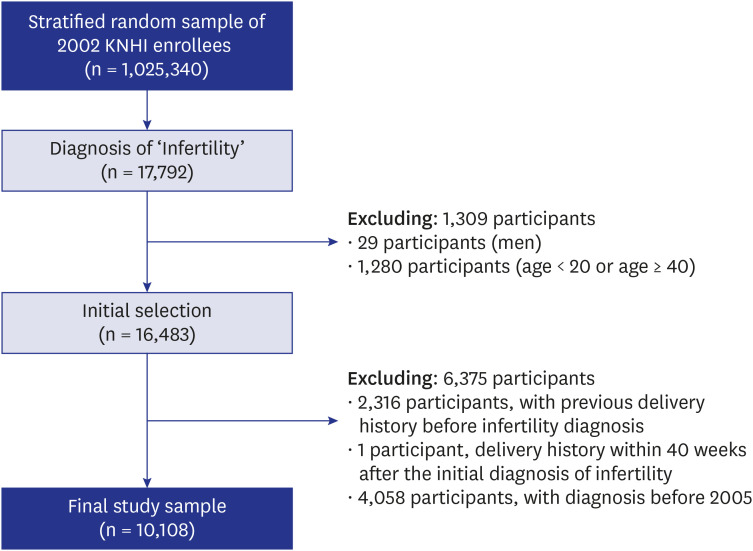

Thus, we investigated the association between socioeconomic status and successful delivery after the initial infertility diagnosis among infertile women aged between 21 to 40.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

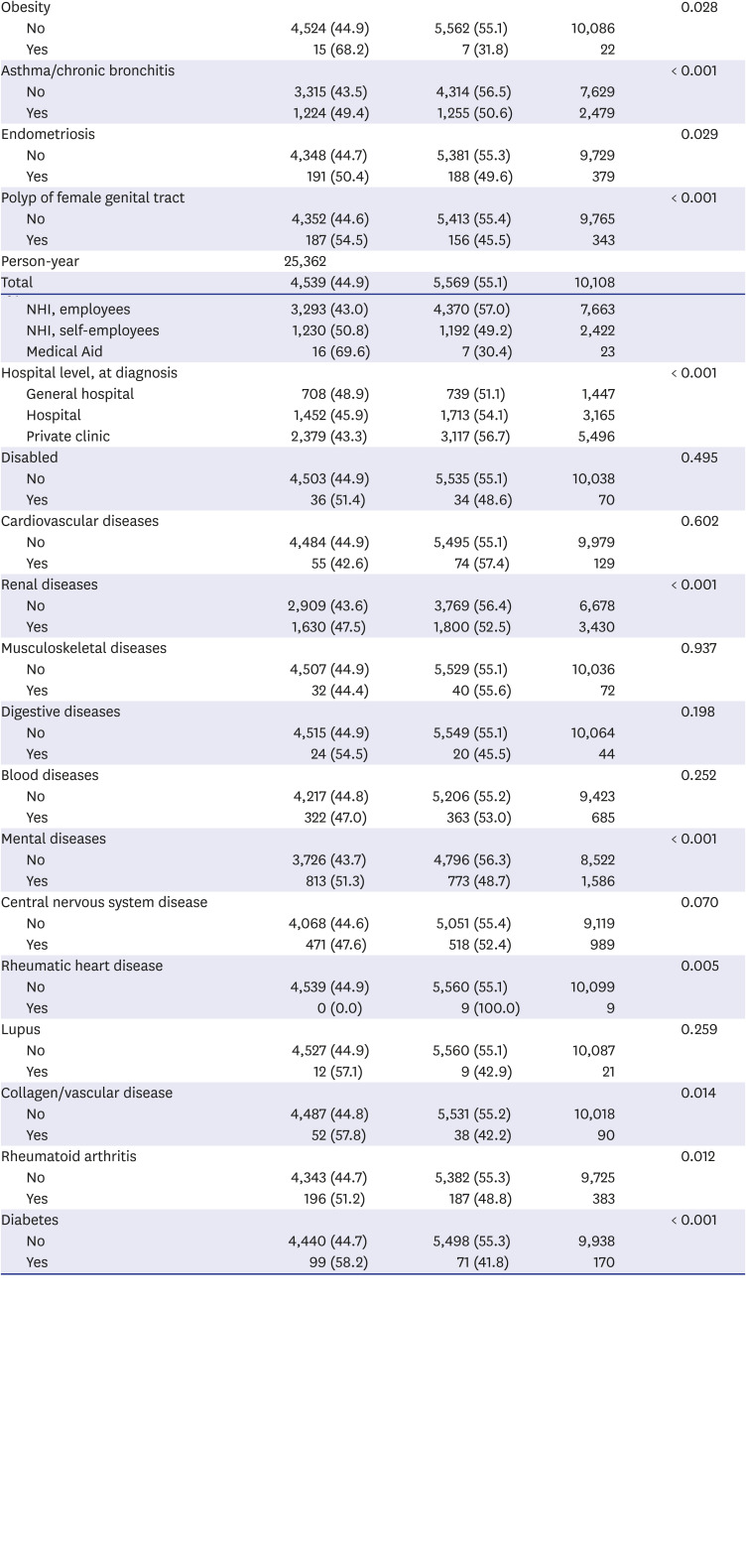

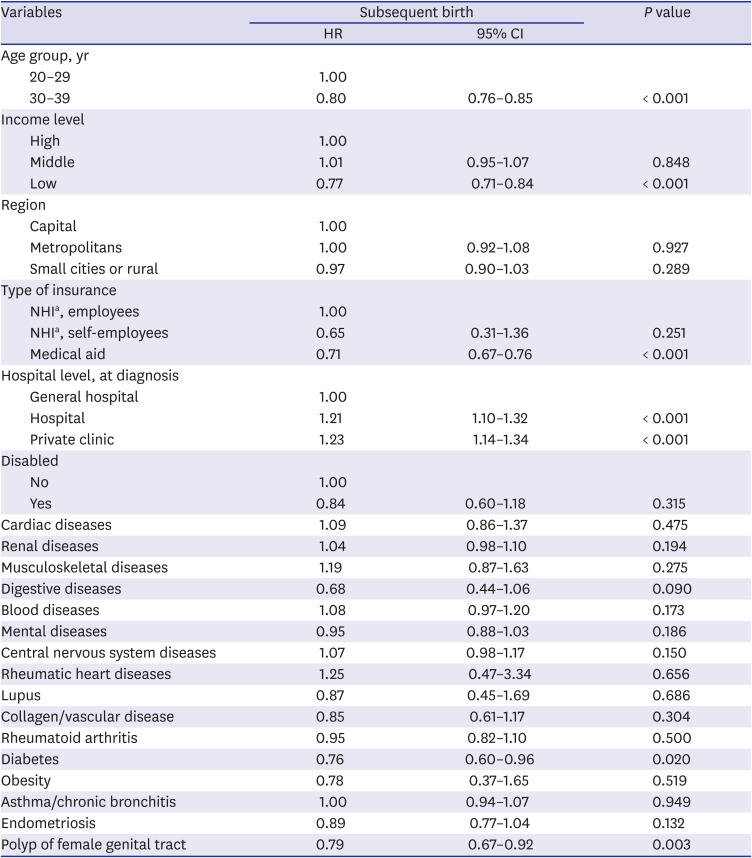

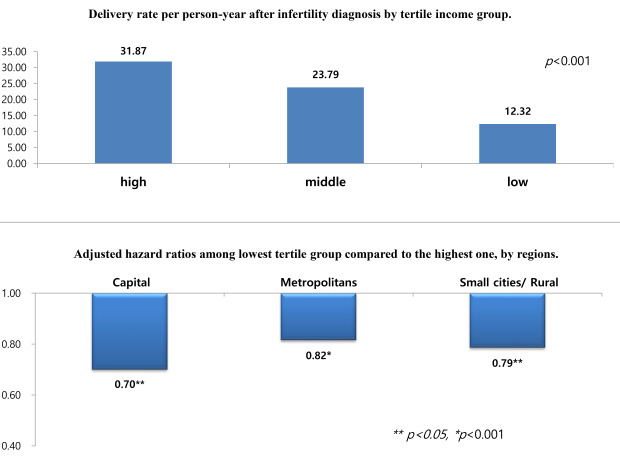

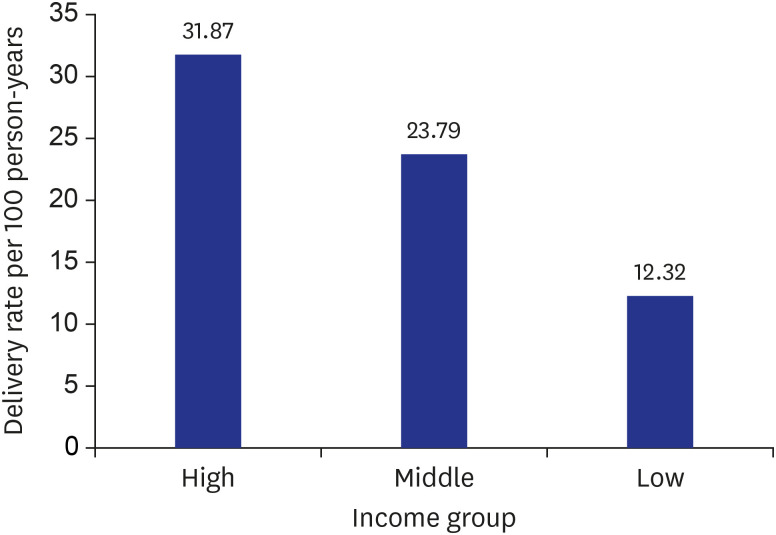

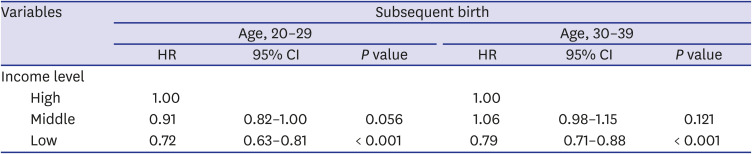

In this study, there are several notable observations from our study. First, among the infertile women, 55.1% ultimately had a medical record for consequent delivery. It took an average of 21.6 months from initial infertility diagnosis to delivery. Second, we identified factors that influenced whether women finally delivered consequently or not. Low-income infertility patients were associated with low HR for subsequent delivery. Furthermore, older age group, diabetes and polyp of female genital tract were also related to low probability for subsequent delivery.

There are several studies regarding the difference in accessibility to fertility clinics across different socioeconomic status.

31315161718 For example, Dhalwani et al.

19 studied the occurrence of fertility problems presenting to primary care. They also estimated clinical burden and socioeconomic inequalities in the UK. In this study, the infertile women aged under 25 were more related to socioeconomic deprivation than the other older patients. In another study in Australia,

18 10.13 and 5.17 fresh assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles per 1,000 women of reproductive age were performed in women in the highest and lowest socioeconomic status quintiles respectively. In the US, socioeconomic factors other than household income were evaluated, such as race/ethnicity, health insurance coverage for infertility services, and education. In this study, educational level and income were related to the infertility treatment use, and education level was strongly associated with achieving a pregnancy.

20

However, similar results were not reported yet in developed Asian countries. Since infertile couples cope with on-going fertility treatments in different manners related to their own cultural and social background, it should be examined in ones’ own society. The reason for limited research regarding the association of socioeconomic status and infertility in Asia might be related to the fact that infertility and involuntary childlessness have traditionally been taboo subjects.

2122 This social conception and stigma still exists even in Hong Kong, which is the most developed city in Asia.

23 As a result, infertility has been a topic which was not easily discussed with others, even with researchers.

22 In most non-western countries, women who do not have children may be regarded as ‘failures’.

2224252627

Despite this social circumstance, the Korean government initiated and has expanded subsidization for fertilization medical procedures. There was implementation of a subsidization policy for IVFs in 2006 and for intrauterine insemination (IUI) in 2010. The income threshold for subsidization is under 150% of the monthly household income. The ministry provides subsidies for up to six IVFs including three fresh embryos and three frozen embryos for low-income infertile couples (four IVFs for fresh embryos only). In terms of IUI, it is subsided four times at most. A total number of 31,152 cases were subsidized in 2013. The average cost for IVFs was 2,670,000 KRW (2,440 USD; 1 USD = 1,095 KRW).

From September 2016, the Korean government decided to a considerable extent to expand this subsidization. First, the government set the new threshold for low-income couples, of which income is less than 100% of average monthly household income. For these couples, additional subsidization with 500,000 KRW and another opportunity for fresh embryo IVF procedure are provided. Moreover, the government also supported middle- and high-income couples for IVF procedures with 1,000,000 KRW. From October 2017, the government started to cover IVF procedures, including four procedures of fresh embryo transfers, three procedures of frozen embryo transfers, and three procedures of internal uterine injections. In July 2019, the government expanded the coverage to seven procedures of fresh embryo transfers, five procedures of frozen embryo transfers, and five procedures of internal uterine injections. The age limit of 40 years or above has been abolished and the out-of-pocket cost burden of IVF has been reduced through partial coverage in health insurance premiums.

However, it is not assured that whether these kinds of expanding health policies will increase the total number of births using ART and reduce the gap between high- and low-income infertility patients for consequent delivery.

First, the medical cost for IVFs is still expensive despite these subsides. According to a national report, 79.3% of IVF procedures were composed of an out-of-pocket cost of 1,800,000 KRW (1,644 USD) or over in 2013. Since the monthly income of the lowest quintile of households in Korea was 1,532,000 KRW in 2013 and the percentage of deficit spending among the lowest quintile income group is 42.5%,

28 most patients in this group would be unable to afford the extra out-of-pocket costs for fertility procedures. Moreover, when we consider that IVF often requires multiple attempts and accessorial charges for tests, it is a burden for infertile couples, especially for low-income couples. These high and repetitive health expenditures might be considered a catastrophic health expenditure, which means that health expenditure in a household is more than 40 percent of a household's annual expenditure, excluding expenditure for food.

2930 In South Africa, one in five couples (22%) incurred catastrophic expenditure. In the poorest tertile group, 51% of households faced catastrophic health expenditure while there were only 2% of households in the richest tertile.

18

Second, low-income couples might not be able to visit experienced hospitals with high successful rates for IVFs. Since the government only provides subsides, rather than covering ARTs under NHI, fertility clinics decide the medical costs for IVF and IUI, and hospitals tend to set higher costs for ART under this unregulated price market. This induced the increased financial burden of accessing good quality fertility clinics for low-income patients. Moreover, since low-income patients usually have less knowledge about assessing quality in healthcare organizations,

3132 there might be quality issues in hospitals which low-income infertile couples usually visit. In fact, ten fertility clinics (6.7% among 150 authorized fertility clinics for IVF) performed 51.3% of all procedures. In terms of IUI, there were 411 authorized clinics. Among them, 292 clinics performed IUI in 2014 and 59.9% of procedures were done by the top twenty clinics. Moreover, among these 292 clinics, 31.8% did not have any successful pregnancy after ART in 2014.

33

Third, the temporal accessibility to fertility clinics hinder low-income patients from visiting clinics. Generally, increased labor force in women is associated with decreased fertility.

343536 For example, the couples who are in poor working environment without a possible replacement are unable to visit fertility clinics repeatedly.

29 Although we could not figure out the direct association between the employment status and accessibility to fertility clinics in this study, it is possible to infer using other references.

The present study has several limitations that should be addressed.

First, the NHICD does not include detailed medical information such as medical reasons for infertility, personal lifestyle, perceived stress, or other environmental factors. Additionally, we did not adjust for the year variable, which might be affected by the reforming of the health insurance coverage policy. Thus, we could not adjust these factors associated with infertility and consequent delivery.

Second, we were not able to determine whether infertility patients used ARTs for consequent delivery or not. The ARTs including IVF and IUI both are not covered by NHI. Thus, NHI Services did not have concrete information for all ARTs.

Third, this cohort data did not contain medical history of spontaneous abortion. Since spontaneous abortion could be sensitive to women in Korea, they did not provide this information.

Fourth, this retrospective cohort study does not support causality between low socioeconomic status and consequent delivery. Although there is a Finnish cohort study that the socioeconomic status is not associated with pregnancy outcome using IVFs,

37 it has not been evaluated in Asians. Thus, it is not certain whether there is a reverse causality or not.

Finally, it is not assured that infertile patients were newly diagnosed from 2005 to 2013. Although we excluded the patients who were already diagnosed as infertile from 2002 to 2004 for three years, there is a possibility that infertile women who were diagnosed before 2002 might have visited after 2005 for further ART trials. Furthermore, this study might have selection bias. We assumed that participants diagnosed with infertility include women who were willing to get pregnant. Therefore, women who were not married, who did not have any intentions to have a baby, or who abandoned having a baby, have been excluded from the study.

In spite of these limitations, we suggest that this nation-wide study showed the association between socioeconomic statuses was associated with consequent delivery after initial diagnosis of infertility. Furthermore, our study might facilitate improving the act: ‘Leave of Absence for Subfertility Treatment (Equal Employment Opportunity and Work-family Balance Assistance Act, Article 18-3).’ Article 18-3 states that ‘when employee applies for a leave of absence to receive subfertility treatment, an employer shall grant a leave of absence to the employee for a period not exceeding three days a year, and the first on day shall be a paid leave of absence.’

38 However, if women received subfertility treatment more than once per year (e.g., possibly 2 or 3 times), more grants for leave of absence and paid leave of absence would be required. Therefore, the policy makers should consider revising the policies and laws regarding subfertility treatment in order to protect employees facing motherhood.

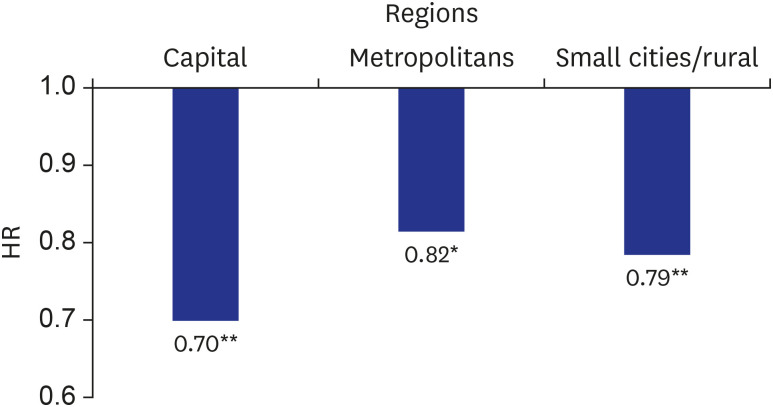

In conclusion, this population-based longitudinal cohort study demonstrated that low-income infertile women have a lower possibility of consequently delivering a baby. And this risk increases in metropolitan areas. Although the Korean government has been expanding subsidies, it might not be enough for low-income households because of persisting financial burden, possible low temporal accessibility, and lack of information on good quality fertility clinics. As the number of infertile couples are increasing and birth rates have dropped steeply, it is necessary to start discussion about coverage from NHI for ARTs.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download