INTRODUCTION

A newly emerging infectious disease, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January and characterized as a pandemic on 11 March by the World Health Organization.

1 The clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection ranged from asymptomatic to rapidly fatal, requiring mechanical ventilation. According to initial data from China, 81% of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection had mild or moderate disease, 14% had severe disease, and 5% had critical illness.

23 The questions regarding who initially presents as severe and which patients among those with asymptomatic or mild presentation become severe or require oxygen therapy are important to clinicians. Answers to these questions will help clinicians prepare for the clinical course and necessary resources such as intensive care or transfer to appropriate facilities. However, studies describing the dynamic change in clinical and laboratory variables among patients initially presenting asymptomatic or mild were rare, and these data are essential for clinicians caring for patients to assess and predict the status at a certain time point.

As COVID-19 is causing a worldwide pandemic, many studies regarding regional clinical features have been reported. The preparedness and strategies for the pandemic are different among countries, and the clinical characteristics of patients admitted to medical facilities seem to vary in different cohorts.

2456 Since the first case of COVID-19,

7 Korea had a strategy of high volume diagnostic testing and early isolation accompanied by contact investigation,

89 and the isolation was lifted after two consecutive negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays from respiratory specimens,

10 The results of this study might lead clinicians to observe the dynamic change in clinical manifestations from the early phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In this study, we presented the temporal dynamic changes of clinical and laboratory variables in patients with asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 infection detected by early active surveillance. The results may help clinicians better understand the clinical course of COVID-19 and prepare for critical care.

METHODS

Study setting

This retrospective analysis was conducted on a multicenter database of all patients aged ≥ 18 years old with SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to the isolation wards of 11 hospitals in Korea and finally discharged between February 20, 2020 and April 30, 2020. The 11 hospitals included Boramae Medical Center, Jeonbuk National University Hospital, Chung-Ang University Hospital, Gangwon-do Wonju Medical Center, Gyeonggi Provincial Medical Center Paju Hospital and Suwon Hospital, Inje University Pusan Paik Hospital, Inje University Sanggye Paik Hospital, Kangwon National University Hospital, Kyunghee University Hospital and Wonju Severance Christian Hospital. There was no limitation of clinical severity for admission to the study hospitals.

Patients

Patients were defined as having SARS-CoV-2 infection if they had a positive real-time reverse transcription PCR result (rRT-PCR) targeting amplification of the E gene, RdRP gene and N gene. Both nasopharyngeal and throat swabs were obtained and mixed for upper respiratory specimens, and sputum or transtracheal aspirates were collected for lower respiratory specimens. After sample collection, RNA extraction and rRT-PCR procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Test kits from 6 domestic commercial manufacturers (Green Cross, Yongin, Korea; Seegene, Seoul, Korea; Kogene, Seoul, Korea; Seoul Clinical Laboratories, Yongin, Korea; SD biosensor, Suwon, Korea; and Institute of Health and Environment, Chuncheon, Korea) were used. Negative conversion of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity was determined with two consecutive rRT-PCR negative results according to the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) guidelines; thus, the patients were discharged from isolation. For patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, follow-up respiratory samples were collected according to the KCDC guidelines.

10 Otherwise, the interval of follow-up testing was determined by the clinicians in charge.

Data collection

Using a standardized case report form, we documented demographics, clinical and laboratory variables, underlying comorbidities, and final outcomes. We recorded daily changes in the dynamic variables, including the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. Therapeutic interventions, including oxygen therapies, mechanical ventilation and antiviral agents, were also recorded. The worst values of the variables during 24 hours of the initial admission or of a daily basis were used. We also assessed the time to SARS-CoV-2 RNA clearance in upper and lower respiratory specimens. Serial changes in laboratory blood tests were followed up for common variables, such as hemoglobin, white blood cell (WBC) count, platelet count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), bilirubin, international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time (PT), and serum creatinine.

Definitions

Regarding underlying comorbidities, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or bronchial asthma had a status of current medication or needing urgent maintenance medication. Chronic heart diseases included ischemic heart diseases, valvular heart diseases, congestive heart failure or arrhythmia on current medication. Chronic liver diseases included liver cirrhosis, chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease or steatohepatitis. Febrile sense was subjectively expressed by patients, and fever was defined as an axillary temperature of 37.5°C or higher. In asymptomatic patients, the date of onset of illness was set as the date of initial diagnosis for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

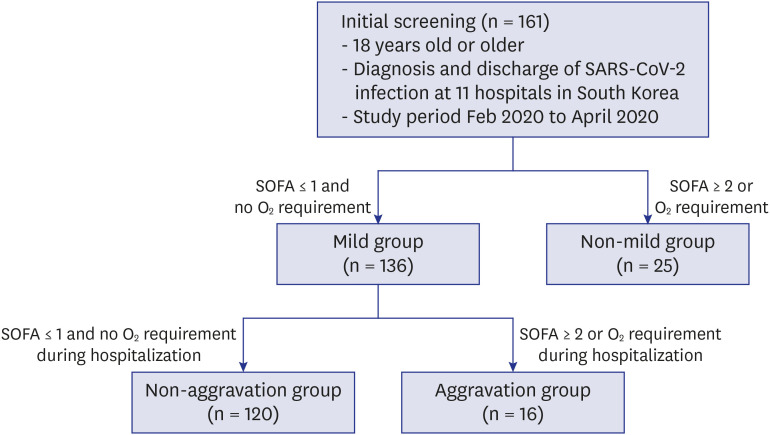

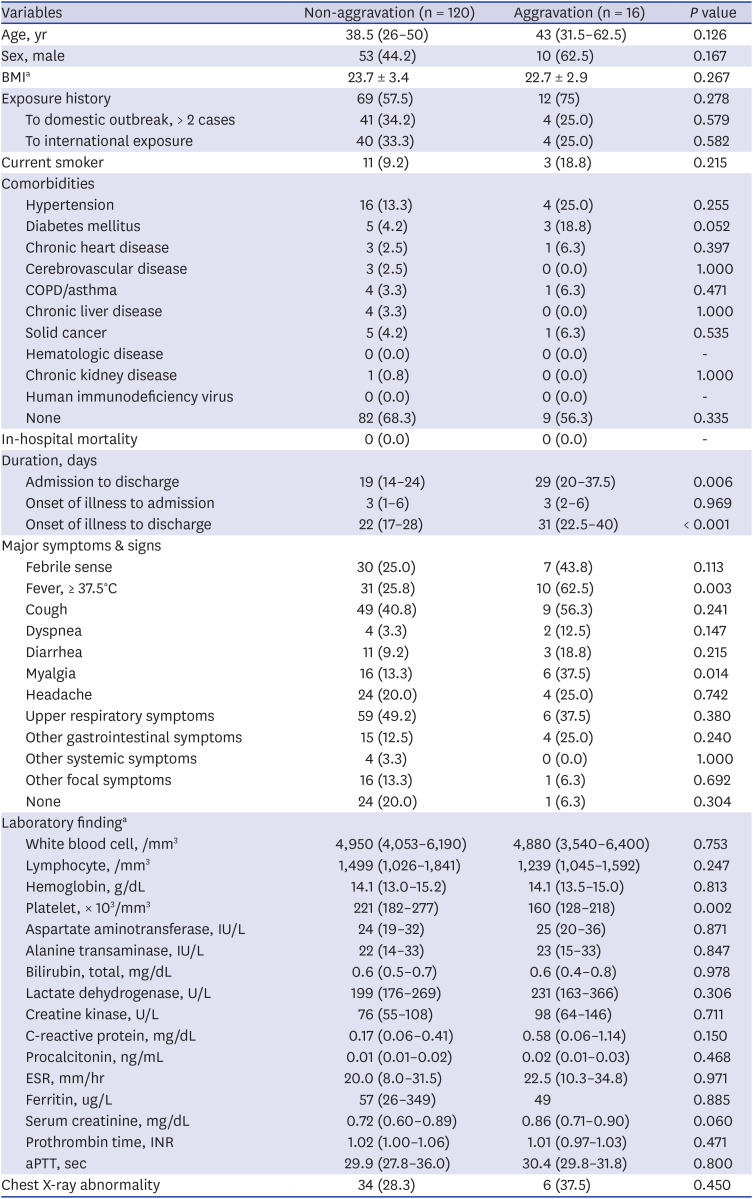

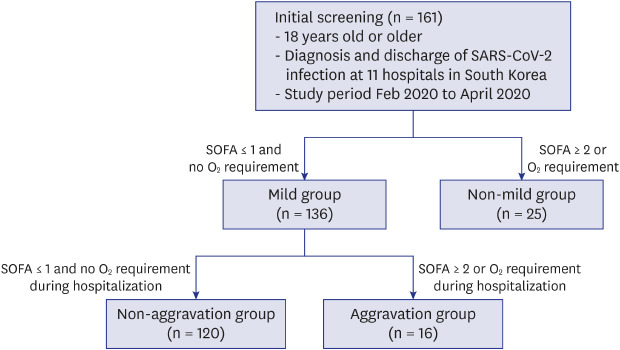

Patients were initially classified into the mild group and non-mild group by evaluating disease severity during the first 24 hours after admission. The mild group was defined as a state with both no oxygen requirement and SOFA score ≤ 1 point. Otherwise, patients were classified as the non-mild group. The mild group was further classified into two subgroups during the clinical course of hospitalization in terms of oxygen requirement and SOFA score (aggravation versus non-aggravation groups) (

Fig. 1). Aggravation was defined as a new oxygen requirement or SOFA score change to ≥ 2. The oxygen requirement was defined as the need for continuous oxygen demand for at least 24 hours. The change in cycle threshold (Ct) value of rRT-PCR testing over the hospital course was analyzed, and the Ct value of the RdRP gene among 3 genes was used.

Fig. 1

Study design. A total of 161 patients were enrolled, with 136 patients in the mild group and 25 patients in the non-mild group. The mild group was subgrouped into the non-aggravation group of 120 patients and the aggravation group of 16 patients during hospitalization.

SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis was performed to test for differences between groups using Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney test and the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, depending on the variable type. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Boramae Medical Center (No. 10-2020-33), and informed consent was waived by the IRB because of the retrospective nature of the study. All personal identifiers were anonymized for confidentiality before data processing. This study was in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

DISCUSSION

The overall clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infection has been described by multiple studies from several countries,

231112 and the current consensus is that the majority of infections have a mild course. Early studies from China showed that 81% of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection had mild or moderate disease, 14% had severe disease, and 5% had critical illness.

3 Factors contributing to severe illness are known to be old age and certain underlying comorbidities, such as hypertension and diabetes.

13 In some series of hospitalized patients, shortness of breath developed a median of 5 to 8 days after initial symptom onset, and its occurrence is suggestive of worsening disease.

14 However, early reports on the clinical features of COVID-19 had limitations in assessing the natural course of the infection due to various degrees of selection bias for the subject patients. Areas with medical conditions overwhelmed by a sudden surge of COVID-19 patients might see more severe patients.

4 There were reports about asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 cases from nonhospital community isolation facilities called ‘Living and treatment centers’ in Korea.

515 Although those patients provided unique chances to observe the clinical characteristics of initial asymptomatic or mild cases of COVID-19, the criteria for admission to those facilities significantly limited the patients to mild cases with age restriction and no underlying comorbidity or well-controlled chronic diseases.

16 These criteria may be used to select low-risk populations for complications in COVID-19 care. The clinical courses of those patients were all uneventful, but their temporal dynamic changes are unknown.

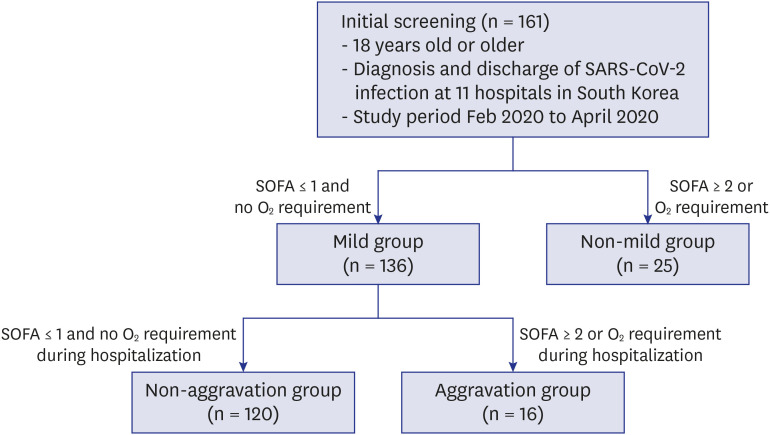

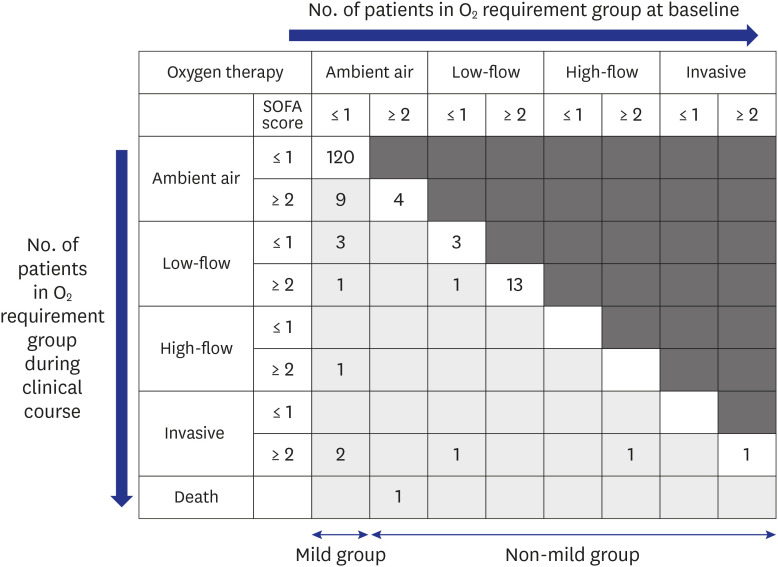

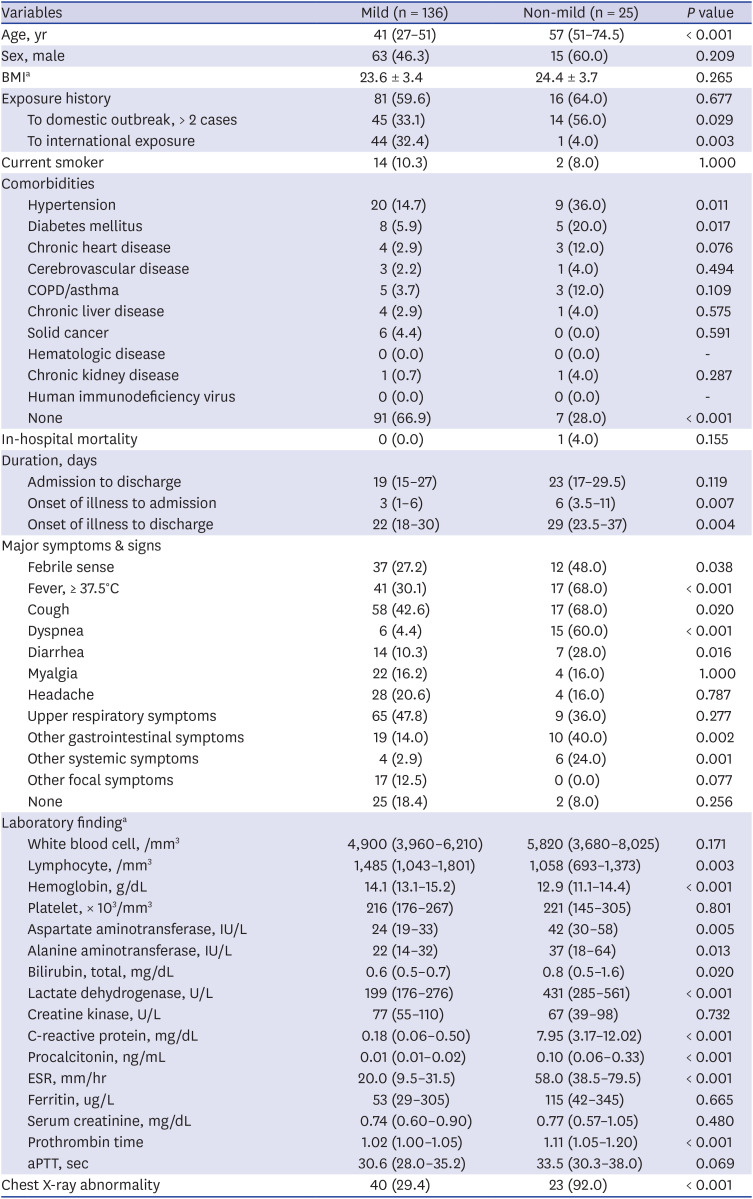

Our cohort in this study showed that 15.5% (25/161) of patients initially presented as non-mild. Old age is known to be associated with severe complications and mortality in COVID-19. Our results suggested that old age (median, 57 years; IQR, 51.0–74.5 years) was also associated with early severe presentation, and 84% of non-mild patients had oxygen demand (

Fig. 2). Dyspnea (60.0%) and elevated levels of CRP (median, 7.35 mg/dL; IQR, 3.17–12.02) indicated severe presentation and could be used to assess patients with COVID-19 for potential oxygen therapy.

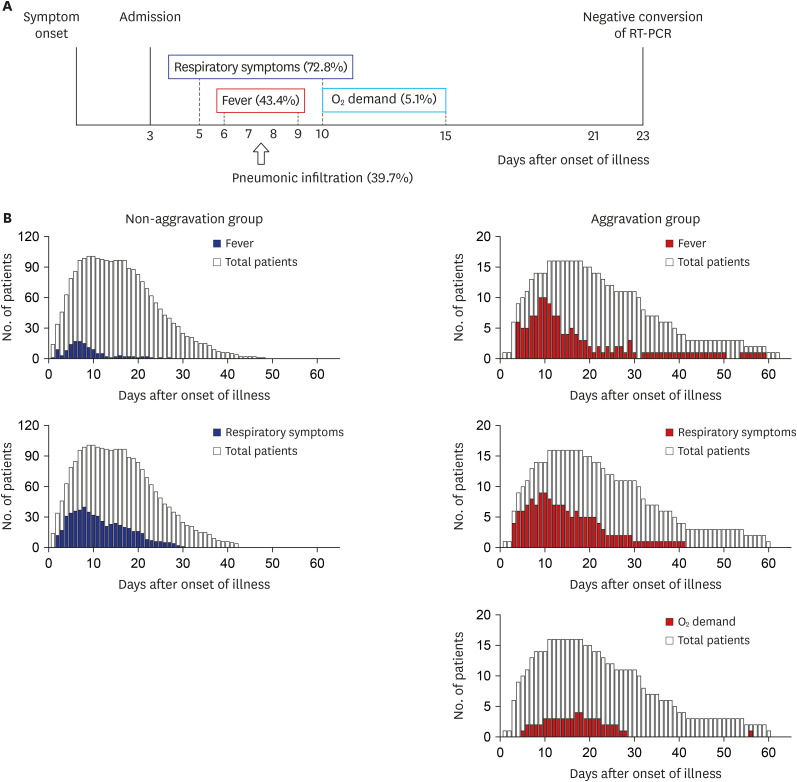

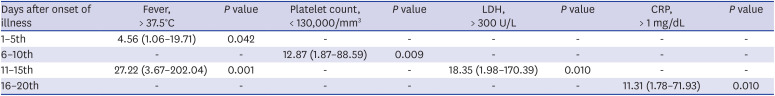

Among the mild group on admission, 11.7% (16/136) of the patients experienced clinical aggravation during hospitalization, but no initial clinical factors could be identified to predict their aggravation during the clinical course. However, several variables, such as lymphopenia and elevated CRP and LDH levels, preceded the aggravation and could be used to monitor patient progression. Most of the oxygen demand occurred in the 1st and 2nd weeks after the onset of illness and rarely after the 3rd week. Therefore, even patients who are mild at presentation need to be followed up until the 3rd week for clinical aggravation with clinical and laboratory assessments. No mortality was observed in the mild group. If we follow clinical aggravation under good comprehension of the usual clinical course and provide optimal supportive care, the outcome may be excellent.

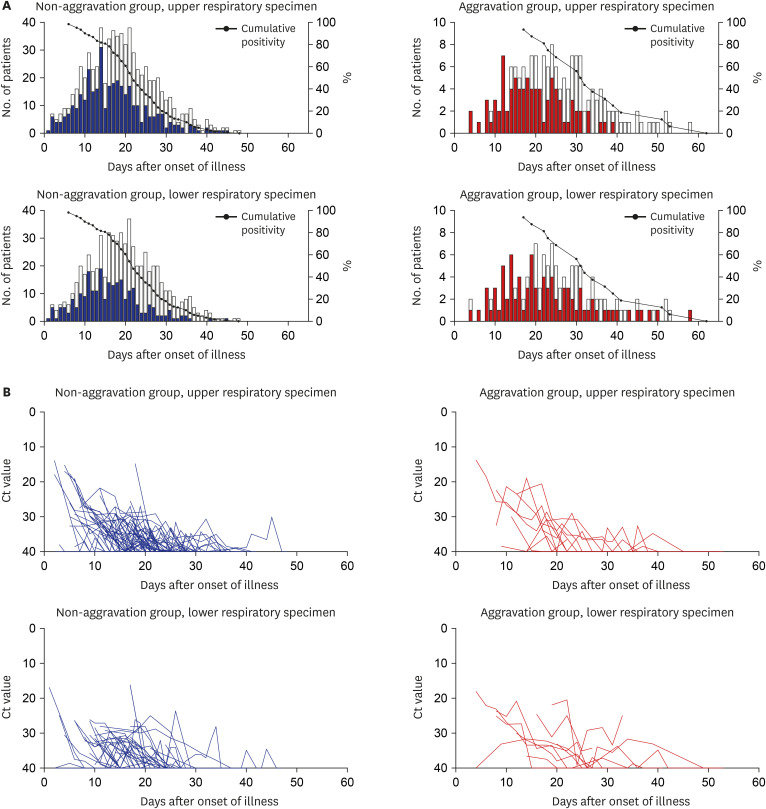

Viral load and its clearance are important considerations. Liu et al.

17 reported that mild cases were found to have an early viral clearance, with 90% of these patients repeatedly testing negative on RT-PCR by day 10 post-onset from nasopharyngeal swab. However, our study showed that RT-PCR positivity lasted for a median of 22 to 32 days after the onset of illness in the initial mild patients, and the cumulative positivity of RT-PCR remained above 32.4%, even at day 28, which was longer than previously reported, especially in the aggravation group (

Fig. 5B and Supplementary Table 3). Clinical aggravation was not related to the initial viral load in our study, but the conclusion was not clear because of our data limitations. However, PCR positivity does not indicate the persistence of viral infectivity.

This study only included fully discharged patients to try to identify the disease course as much as possible. As there was no surge of patients overwhelming the medical capacity surrounding the study hospitals, medical care in each hospital was within ordinary standard of care. Therefore, there might be little distortion of the natural course of disease due to a lack of medical resources. However, there were some limitations. First, as this study was a retrospective study, subjective symptoms could not be adequately serially quantified. Second, the number of total cases was not enough to adequately perform the risk factor analysis. Third, individual hospitals used their test kits from six domestic commercial products. Although all of them were certified by KCDC, the absolute Ct values might be slightly different between the products. So, the interpretation of trend rather than absolute comparison of the Ct values is needed.

In conclusion, we observed a cohort of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients screened early by national policy. Old age was associated with early severe presentation. Clinical aggravation among asymptomatic or mild patients could not be predicted initially but was heralded by fever and several laboratory markers, such as thrombocytopenia, and elevated levels of CRP and LDH during the clinical course. Viral clearance took a median of 22 to 32 days after the onset of illness. Our study may help in understanding the natural course of mild COVID-19 and prepare for the possible next waves of disease.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download