Quarantine is vital for minimizing the risk of disease transmission, especially during outbreaks of viral respiratory infections.

1 In the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, many government bodies are pursuing contact tracing and imposing self-isolation in order to slow the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

23 Quarantine inevitably leads to separation from family members, and restriction of liberty.

45 Therefore, quarantine often provokes negative psychological consequences such as anxiety, depression, and anger,

678910 which may lead to dire consequences such as suicide.

11 Previous studies mainly focused on the psychological impact of quarantine on hospital staff or adult patients,

121314 and less frequently focused on young patients

15 and the caregivers under quarantine with their young patients.

1516

On March 26, 2020, a 9-year-old girl was referred to our pediatric emergency room from another hospital for intracerebral hemorrhage. On arrival, she developed a fever of 38.1°C, and was tested for SARS-CoV-2 PCR (Allplex 2019-nCoV kit; Seegene, Seoul, Korea), whose results were negative. On March 31, however, an outbreak was reported at the previous hospital where she had visited, and her second test for SARS-CoV-2 PCR was positive. The epidemiologic investigator of the city of Seoul decided to implement cohort isolation for all patients and their caregivers who stayed at the same ward and the other wards on the same floor as well as those who had close contacts with the index patient. On April 4, a mother of a pediatric patient who shared the six-patient room with the index patient was also confirmed to be positive for SARS-CoV-2. The infection control team at our hospital identified the close contacts with the second patient. As a result, 62 patients and 72 caregivers were quarantined at four COVID-19 isolation units of our children's hospital for 2 weeks according to the incubation period of SARS-CoV-2.

17

As of the second day of the quarantine, both the caregivers and the patients developed psychological distress; as such, we established a psychiatric consultation team on the third day of the quarantine, and every caregiver underwent at least one psychiatry evaluation. A total number of 6 board-certified psychiatrists interviewed the caregivers and the nursing staffs and identified psychological and behavioral responses as well as stressors of caregivers.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients and the caregivers were collected. The psychological and behavioral responses and stressors of the caregivers were classified according to Brooks et al.'s review,

6 which extensively revealed numerous emotional outcomes as well as specific stressors of quarantined people and of health care providers. It was thoroughly reviewed by the consultation team and considered to be adequate to apply to those under quarantine as suggested by a perspective article.

18 Interventions provided to each patient and/or every caregiver were also recorded. Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages and continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 24 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Seventy-two caregivers of 62 patients who were quarantined at the Children's Hospital were analyzed. The mean age of the patients was 5.2 ± 5.5 years (range, 15 days–22 years) and 33 (53.2%) were male. The most common diagnosis of the patients was gastrointestinal diseases (n = 17 [27.4%]), followed by congenital heart diseases (n = 12 [19.4%]), musculoskeletal diseases (n = 8 [12.9%]), neoplasms (n = 8 [12.9%]), neurologic disease (n = 5 [8.1%]), pulmonary disease (n = 5 [8.1%]), hepatobiliary disease (n = 2 [3.2%]), urinary tract obstruction (n = 2 [3.2%], and others (n = 3 [4.8%]). The mean age of the caregivers was 39.2 ± 8.9 years (range, 19–73 years), and 54 (75.0%) were female. The caregivers comprised 67 (93.1%) parents, 3 (4.2%) grandmothers, 1 (1.4%) sister, and 1 (1.4%) personal care assistant. Two (2.8%) had been diagnosed with adjustment disorder and 1 (1.4%) with depressive disorder. Among them, two (2.8%) had previously taken psychotropic medications, and none of them were taking psychotropic medication at the time of exposure to the patient with COVID-19.

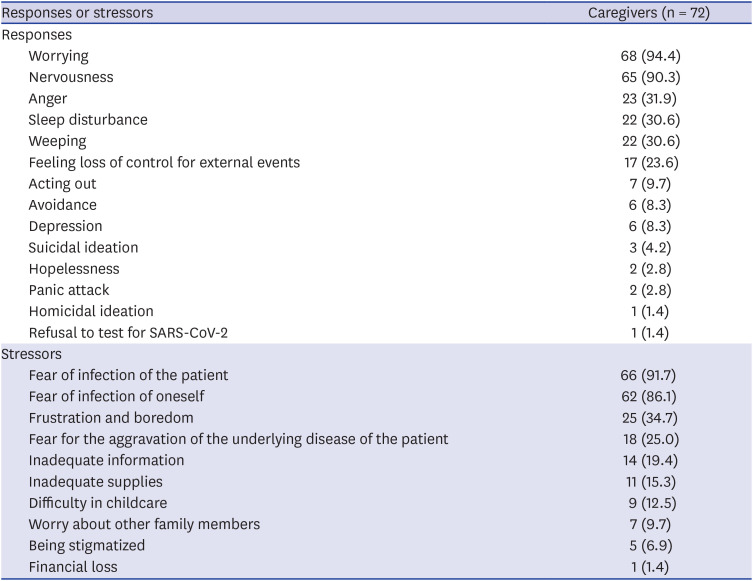

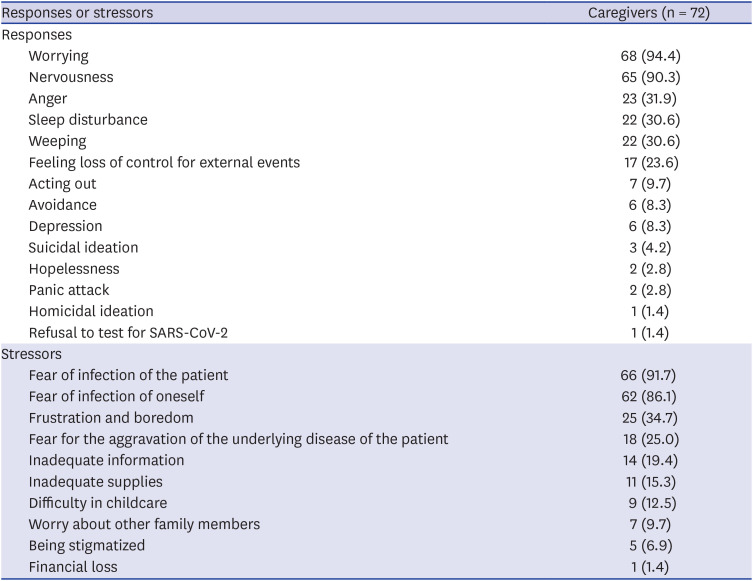

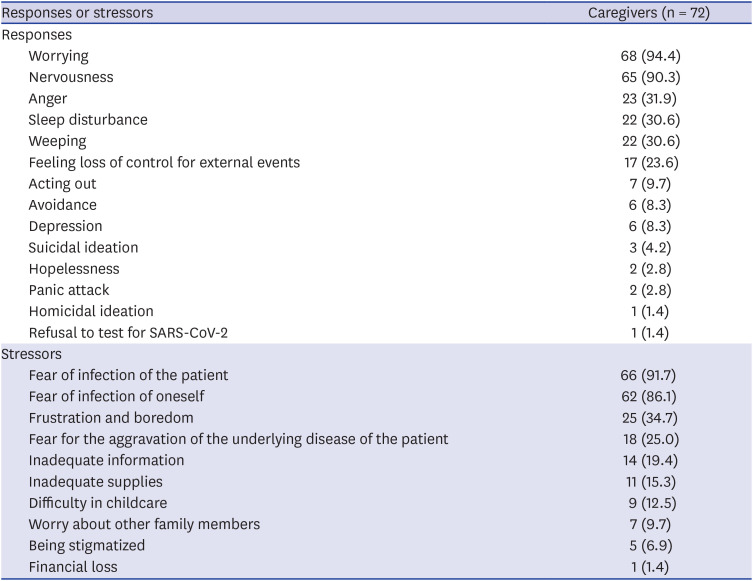

The psychological and behavioral responses and stressors of the caregivers are listed in

Table 1. Worrying (94.4%) and nervousness (90.3%) were observed in more than 90% of the caregivers. Three caregivers manifested suicidal ideation (4.2%), and one reported homicidal ideation (1.4%). As for stressors of caregivers, fear of infection of the patient (91.7%) and fear of infection of oneself (86.1%) were highly prevalent among the caregivers.

Table 1

Psychological and behavioral responses and stressors of the caregivers during quarantine

|

Responses or stressors |

Caregivers (n = 72) |

|

Responses |

|

|

Worrying |

68 (94.4) |

|

Nervousness |

65 (90.3) |

|

Anger |

23 (31.9) |

|

Sleep disturbance |

22 (30.6) |

|

Weeping |

22 (30.6) |

|

Feeling loss of control for external events |

17 (23.6) |

|

Acting out |

7 (9.7) |

|

Avoidance |

6 (8.3) |

|

Depression |

6 (8.3) |

|

Suicidal ideation |

3 (4.2) |

|

Hopelessness |

2 (2.8) |

|

Panic attack |

2 (2.8) |

|

Homicidal ideation |

1 (1.4) |

|

Refusal to test for SARS-CoV-2 |

1 (1.4) |

|

Stressors |

|

|

Fear of infection of the patient |

66 (91.7) |

|

Fear of infection of oneself |

62 (86.1) |

|

Frustration and boredom |

25 (34.7) |

|

Fear for the aggravation of the underlying disease of the patient |

18 (25.0) |

|

Inadequate information |

14 (19.4) |

|

Inadequate supplies |

11 (15.3) |

|

Difficulty in childcare |

9 (12.5) |

|

Worry about other family members |

7 (9.7) |

|

Being stigmatized |

5 (6.9) |

|

Financial loss |

1 (1.4) |

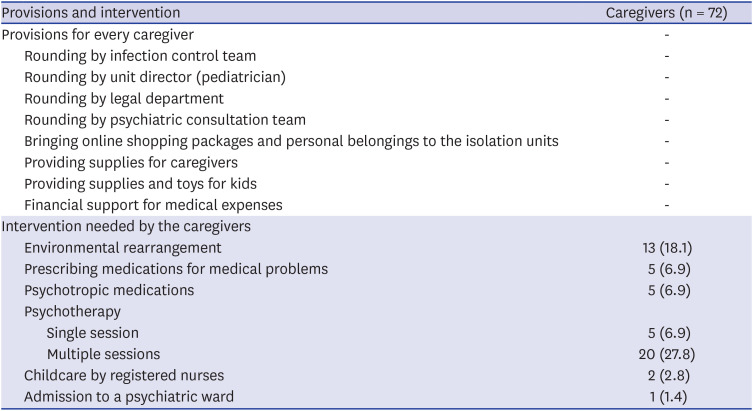

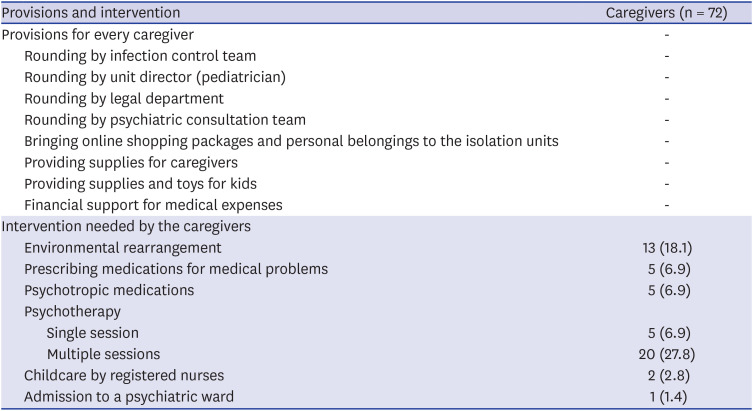

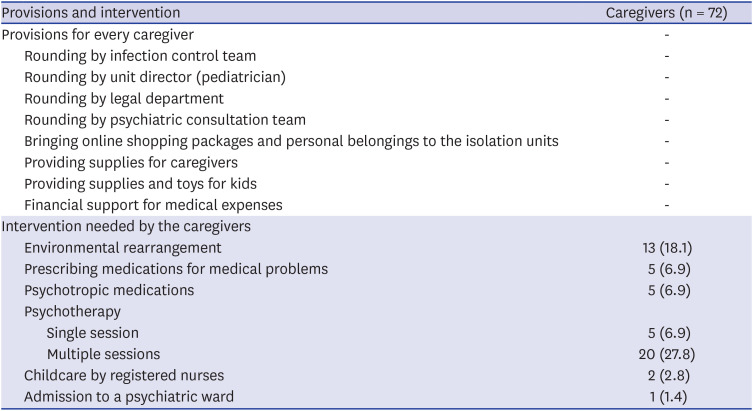

To reduce the stressors such as inadequate supplies and inadequate information, the following provisions were available to the caregivers and the patients. The patients received regular rounding by the patient's attending physician, the infection control team, unit director (pediatrician), legal department, and the psychiatric consultation team. Any inadequacies in basic supplies were fully addressed by providing daily necessities such as food, drinking water, clothes, underwear, sanitary napkins, and toys. Moreover, online shopping packages and personal belongings were brought to the isolation units upon caregivers' requests. The basic supplies and other belongings were delivered by nursing staffs. If caregivers reported lack of information which occurred due to quarantine, they were allowed to ask attending physicians and/or a member of infection control team during regular rounding. Potential legal conflicts (e.g., financial loss due to mandatory quarantine) were consulted by legal department. All medical expenses and the supplies were covered by the hospital.

The specific interventions needed by individual caregivers are shown in

Table 2. Thirteen (18.1%) caregivers asked for environmental rearrangements such as temperature adjustment and provision of adequate spaces and nursing staffs of the isolation units managed the requirement accordingly if possible. Two (2.8%) caregivers had difficulties in taking care of the newborn babies and required babysitting by the nursing staffs. Five (6.9%) caregivers were prescribed medications such as painkillers for joint pain, topical agents for skin rash, and antihistamine for allergic rhinitis by their attending physicians or infection control team. A single session of supportive psychotherapy was needed in 5 (6.9%) caregivers and multiple sessions were needed in 20 (27.8%) caregivers. Psychiatrists prescribed psychotropic medication to 5 (6.9%) patients (antidepressant, n = 3; benzodiazepine, n = 2). One (1.4%) caregiver was admitted to the Department of Psychiatry because of suicidal ideation. Every intervention was adjusted and harmonized by infection control team and the unit director.

Table 2

Provisions and intervention for the caregivers during quarantine

|

Provisions and intervention |

Caregivers (n = 72) |

|

Provisions for every caregiver |

- |

|

Rounding by infection control team |

- |

|

Rounding by unit director (pediatrician) |

- |

|

Rounding by legal department |

- |

|

Rounding by psychiatric consultation team |

- |

|

Bringing online shopping packages and personal belongings to the isolation units |

- |

|

Providing supplies for caregivers |

- |

|

Providing supplies and toys for kids |

- |

|

Financial support for medical expenses |

- |

|

Intervention needed by the caregivers |

|

|

Environmental rearrangement |

13 (18.1) |

|

Prescribing medications for medical problems |

5 (6.9) |

|

Psychotropic medications |

5 (6.9) |

|

Psychotherapy |

|

|

|

Single session |

5 (6.9) |

|

|

Multiple sessions |

20 (27.8) |

|

Childcare by registered nurses |

2 (2.8) |

|

Admission to a psychiatric ward |

1 (1.4) |

In this study, the caregivers had a higher prevalence of worrying, nervousness, and fear of infection compared with the subjects in the preceding studies.

1215192021222324 While most previous studies focused on the psychological reactions of hospital staff or those under voluntary self-isolation at home, we focused on the psychological and behavioral responses of caregivers of young patients with underlying illnesses under compulsory isolation in hospital units. Moreover, we evaluated the caregivers during a 2-week quarantine period, thus reflecting more severe and acute psychological reactions. Our results suggest that significant clinical attention is required in caregivers of young patients under mandatory quarantine.

The psychological adverse effects of quarantine could be dramatic and severe in some cases. In our study, 3 caregivers reported suicidal ideations and 1 reported homicidal ideations. One female caregiver was eventually admitted to the Department of Psychiatry because of suicidality. A study on previous epidemics showed that cases of completed or attempted suicides were reported during the first weeks of the imposition of quarantine.

1125 These results collectively suggest that the mental health of children

26 as well as caregivers should be closely monitored during quarantine.

A multidisciplinary team approach was essential for fully comprehending and addressing the caregivers' unmet demands.

2728 In line with previous research,

2329303132 caregivers reported that inadequacies in supplies, medication, and information as well as difficulty in childcare were major stressors. We sought to follow the suggestions from Brooks et al.'s review

6 by providing as much information and supplies as possible, reducing the boredom, and improving the communication. To achieve these goals, we fully encouraged open communication between multidisciplinary teams consisting of the infection control team, unit director (pediatrician), legal team, psychiatrists, and nursing staff.

Several limitations should be taken into consideration. Psychological distress or stressor was not evaluated based on a semi-structured interview or clinical rating scale. Therefore, the degree of the psychological impacts of quarantine, which could vary among subjects, was not estimated. In addition, this study did not consider several other clinical characteristics that could be associated with the distress of isolated caregivers (i.e., personality, coping strategy, previous experience of isolation, or past psychiatric history

3334).

In conclusion, mandatory quarantine at a children's hospital due to contact with a patient with COVID-19 had notable psychological impacts on the caregivers. The decision to impose a large-scale quarantine in healthcare facilities should be made carefully by considering the possible psychological ramifications on the caregivers as well as the patients. Potential benefits of mandatory mass quarantine need to be weighed carefully against the possible psychological costs. When such quarantine must be pursued, thorough psychiatric evaluation and intervention through a multidisciplinary approach may be helpful in reducing the caregivers' stressors.