1. Munthe-Kaas HM, Johansen S, Blaasvaer N, Hammerstrom KT, Nilsen W. The Effect of Psychosocial Interventions for Preventing and Treating Depression and Anxiety Among At-Risk Children and Adolescents. Oslo, Norway: Knowledge Centre for the Health Services at The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH);2014.

2. Gillies D, Taylor F, Gray C, O'Brien L, D'Abrew N. Psychological therapies for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 12:CD006726. PMID:

23235632.

3. World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the Management of Conditions Specifically Related to Stress. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO;2013.

4. Lee MS, Hwang JW, Lee CS, Kim JY, Lee JH, Kim E, et al. Development of post-disaster psychosocial evaluation and intervention for children: Results of a South Korean Delphi panel survey. PLoS One. 2018; 13(3):e0195235. PMID:

29596483.

5. Gillies D, Maiocchi L, Bhandari AP, Taylor F, Gray C, O'Brien L. Psychological therapies for children and adolescents exposed to trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; 10:CD012371. PMID:

27726123.

6. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Staron VR. A pilot study of modified cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood traumatic grief (CBT-CTG). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006; 45(12):1465–1473. PMID:

17135992.

7. Wicking M, Maier C, Tesarz J, Bernardy K. EMDR as a psychotherapeutic approach in the treatment of chronic pain: is eye movement desensitization and reprocessing an effective therapy for patients with chronic pain who do not suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder? Schmerz. 2017; 31(5):456–462. PMID:

28656479.

8. Every-Palmer S, Flewett T, Dean S, Hansby O, Colman A, Weatherall M, et al. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in adults with serious mental illness within forensic and rehabilitation services: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019; 20(1):642. PMID:

31753032.

9. van Schagen AM, Lancee J, de Groot IW, Spoormaker VI, van den Bout J. Imagery rehearsal therapy in addition to treatment as usual for patients with diverse psychiatric diagnoses suffering from nightmares: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015; 76(9):e1105–13. PMID:

26455674.

10. Berlin KL, Means MK, Edinger JD. Nightmare reduction in a Vietnam veteran using imagery rehearsal therapy. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010; 6(5):487–488. PMID:

20957851.

11. Church D, Stern S, Boath E, Stewart A, Feinstein D, Clond M. Emotional freedom techniques to treat posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: review of the evidence, survey of practitioners, and proposed clinical guidelines. Perm J. 2017; 21:16–100.

12. Wang HR, Bahk WM, Seo JS, Woo YS, Park YM, Jeong JH, et al. Korean medication algorithm for depressive disorder: comparisons with other treatment guidelines. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2017; 15(3):199–209. PMID:

28783928.

13. Park JH, Lee MS, Chang HY, Hwang JW, Lee JH, Kim JY, et al. The major elements of psychological assessment and intervention for children and adolescents after a disaster: a professional Delphi preliminary survey. J Korean Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016; 27(3):164–172.

14. Industry-University Cooperation Foundation Hanyang University. Development of Stabilization Program for Trauma Recovery. Seoul, Korea: National Center for Mental Health;2015.

15. Kim D, Lee H, Min J. Basic Treatment Protocol Manual for Disaster Surviors. Seoul, Korea: SIID Communication;2019.

16. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Kliethermes M, Murray LA. Trauma-focused CBT for youth with complex trauma. Child Abuse Negl. 2012; 36(6):528–541. PMID:

22749612.

17. Shapiro F. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): Basic Principles, Protocols and Procedures. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press;2001.

18. Krakow B, Zadra A. Clinical management of chronic nightmares: imagery rehearsal therapy. Behav Sleep Med. 2006; 4(1):45–70. PMID:

16390284.

20. Solon R. Providing Psychological First Aid following a disaster. Occup Health Saf. 2016; 85(5):40–42.

21. Lee MS, Hwang JW, Lee CS, Kim JY, Lee JH, Kim EJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents after a disaster: a systematic literature review (1991–2015). J Korean Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016; 27(4):278–305.

22. Watkins LE, Sprang KR, Rothbaum BO. Treating PTSD: a review of evidence-based psychotherapy interventions. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018; 12:258. PMID:

30450043.

23. Schneider G, Nabavi D, Heuft G. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in a patient with comorbid epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005; 7(4):715–718. PMID:

16246634.

24. Trentini C, Lauriola M, Giuliani A, Maslovaric G, Tambelli R, Fernandez I, et al. Dealing with the aftermath of mass disasters: a field study on the application of EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol with child survivors of the 2016 Italy Earthquakes. Front Psychol. 2018; 9:862. PMID:

29915550.

25. Carlson JG, Chemtob CM, Rusnak K, Hedlund NL, Muraoka MY. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EDMR) treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1998; 11(1):3–24. PMID:

9479673.

26. Church D, Sparks T, Clond M. EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) and resiliency in veterans at risk for PTSD: a randomized controlled trial. Explore (NY). 2016; 12(5):355–365. PMID:

27543343.

27. Wilson SA, Becker LA, Tinker RH. Fifteen-month follow-up of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder and psychological trauma. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997; 65(6):1047–1056. PMID:

9420367.

28. Putois B, Peter-Derex L, Leslie W, Braboszcz C, El-Hage W, Bastuji H. Internet-based intervention for posttraumatic stress disorder: using remote imagery rehearsal therapy to treat nightmares. Psychother Psychosom. 2019; 88(5):315–316. PMID:

31284286.

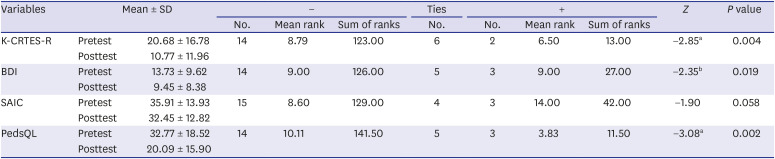

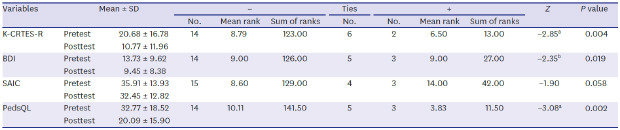

30. Napper LE, Fisher DG, Jaffe A, Jones RT, Lamphear VS, Joseph L, et al. Psychometric properties of the Child's Reaction to Traumatic Events Scale-Revised in English and Lugandan. J Child Fam Stud. 2015; 34(5):1285–1294. PMID:

26085785.

31. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961; 4(6):561–571. PMID:

13688369.

32. Richter P, Werner J, Bastine R, Heerlein A, Kick H, Sauer H. Measuring treatment outcome by the Beck Depression Inventory. Psychopathology. 1997; 30(4):234–240. PMID:

9239795.

33. Saal W, Kagee A, Bantjes J. Utility of the Beck Depression Inventory in measuring major depression among individuals seeking HIV testing in the Western Cape, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2018; 30(sup1):29–36. PMID:

30021462.

34. Spielberger CD. Manual for State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press;1972.

35. Desai AD, Zhou C, Stanford S, Haaland W, Varni JW, Mangione-Smith RM. Validity and responsiveness of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 4.0 generic core scales in the pediatric inpatient setting. JAMA Pediatr. 2014; 168(12):1114–1121. PMID:

25347549.

36. Buck D, Clarke MP, Powell C, Tiffin P, Drewett RF. Use of the PedsQL in childhood intermittent exotropia: estimates of feasibility, internal consistency reliability and parent-child agreement. Qual Life Res. 2012; 21(4):727–736. PMID:

21786058.

37. Martinez JI, Lau AS, Chorpita BF, Weisz JR. Research Network on Youth Mental Health. Psychoeducation as a mediator of treatment approach on parent engagement in child psychotherapy for disruptive behavior. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017; 46(4):573–587. PMID:

26043317.

38. Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Chang S, Langley A, Peris T, Wood JJ, et al. Controlled comparison of family cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation/relaxation training for child obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011; 50(11):1149–1161. PMID:

22024003.

39. Birkhead GS, Vermeulen K. Sustainability of Psychological First Aid training for the disaster response workforce. Am J Public Health. 2018; 108(S5):S381–S382. PMID:

30260696.

40. Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen LR, Han H. Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: a phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002; 70(5):1067–1074. PMID:

12362957.

41. Laliberté Durish C, Pereverseff RS, Yeates KO. Depression and depressive symptoms in pediatric traumatic brain injury: a scoping review. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018; 33(3):E18–30.

42. Vares EA, Salum GA, Spanemberg L, Caldieraro MA, Souza LH, Borges RP, et al. Childhood trauma and dimensions of depression: a specific association with the cognitive domain. Br J Psychiatry. 2015; 38(2):127–134.

43. Iverson KM, King MW, Cunningham KC, Resick PA. Rape survivors' trauma-related beliefs before and after cognitive processing therapy: associations with PTSD and depression symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2015; 66:49–55. PMID:

25698164.

44. Oh W, Muzik M, McGinnis EW, Hamilton L, Menke RA, Rosenblum KL. Comorbid trajectories of postpartum depression and PTSD among mothers with childhood trauma history: course, predictors, processes and child adjustment. J Affect Disord. 2016; 200:133–141. PMID:

27131504.

45. Lehmann S, Havik OE, Havik T, Heiervang ER. Mental disorders in foster children: a study of prevalence, comorbidity and risk factors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013; 7(1):39. PMID:

24256809.

46. Humphreys KL, LeMoult J, Wear JG, Piersiak HA, Lee A, Gotlib IH. Child maltreatment and depression: a meta-analysis of studies using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2020; 102:104361. PMID:

32062423.

47. Hagen KA, Olseth AR, Laland H, Rognstad K, Apeland A, Askeland E, et al. Evaluating Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma and Conduct Problems (MATCH-ADCT) in Norwegian child and adolescent outpatient clinics: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019; 20(1):16. PMID:

30616662.

48. Lucassen MF, Stasiak K, Crengle S, Weisz JR, Frampton CM, Bearman SK, et al. Modular approach to therapy for anxiety, depression, trauma, or conduct problems in outpatient child and adolescent mental health services in New Zealand: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015; 16(1):457. PMID:

26458917.

49. Chemtob CM, Griffing S, Tullberg E, Roberts E, Ellis P. Screening for trauma exposure, and posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms among mothers receiving child welfare preventive services. Child Welfare. 2011; 90(6):109–127. PMID:

22533045.

50. Tutus D, Keller F, Sachser C, Pfeiffer E, Goldbeck L. Change in parental depressive symptoms in trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017; 27(2):200–205. PMID:

28051337.

51. Dominguez S, Drummond P, Gouldthorp B, Janson D, Lee CW. A randomized controlled trial examining the impact of individual trauma-focused therapy for individuals receiving group treatment for depression. Psychol Psychother. Forthcoming. 2020; DOI:

10.1111/papt.12268.

52. Iverson KM, Gradus JL, Resick PA, Suvak MK, Smith KF, Monson CM. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD and depression symptoms reduces risk for future intimate partner violence among interpersonal trauma survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011; 79(2):193–202. PMID:

21341889.

53. Paauw C, de Roos C, Tummers J, de Jongh A, Dingemans A. Effectiveness of trauma-focused treatment for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019; 10(1):1682931. PMID:

31762948.

54. Lee YJ, Lee MS, Won SD, Lee SH. Post-traumatic stress, quality of life and alcohol use problems among out-of-school youth. Psychiatry Investig. 2019; 16(3):193–198.

55. Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza B, Sise MJ, Sack DI, et al. Trauma in adolescents causes long-term marked deficits in quality of life: adolescent children do not recover preinjury quality of life or function up to two years postinjury compared to national norms. J Trauma. 2007; 62(3):577–583. PMID:

17414331.

56. Schneeberg A, Ishikawa T, Kruse S, Zallen E, Mitton C, Bettinger JA, et al. A longitudinal study on quality of life after injury in children. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016; 14(1):120. PMID:

27561258.

57. Rosenberg M, Ramirez M, Epperson K, Richardson L, Holzer C 3rd, Andersen CR, et al. Comparison of long-term quality of life of pediatric burn survivors with and without inhalation injury. Burns. 2015; 41(4):721–726. PMID:

25670250.

58. Anzarut A, Chen M, Shankowsky H, Tredget EE. Quality-of-life and outcome predictors following massive burn injury. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005; 116(3):791–797. PMID:

16141817.

59. Ravens-Sieberer U, Karow A, Barthel D, Klasen F. How to assess quality of life in child and adolescent psychiatry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014; 16(2):147–158. PMID:

25152654.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download