INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common clinical syndrome with significant morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients.

12 It also has been increasingly recognized as the major risk factor for the development and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and a recent United States Renal Data System report showed that acute tubular necrosis (ATN) with no recovery is responsible for 2%–3% of the annual incidence of end stage renal disease (ESRD) cases.

3 However, despite this huge clinical impact, long-term outcome of AKI still remains unclear.

In the spectrum of AKI, ATN, caused by ischemia, toxins, or sepsis, is the most common cause of intrinsic AKI and characterized by patchy or diffuse denudation of renal tubular cells with loss of the brush border and intratubular obstruction with sparing of glomeruli.

4 However, despite these well characterized pathological features of ATN, it is usually diagnosed clinically without histological confirmation. In contrast, disease affecting the interstitium with infiltration of lymphocytes and eosinophils, termed acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is usually diagnosed by kidney biopsy and is increasingly recognized as an important cause of AKI.

567

While kidney biopsy is a gold standard not only in diagnosis but also in prediction of outcome in various glomerular diseases, it is not usually performed in AKI. Kidney biopsy in AKI is usually indicated in the presence of active urinary sediment with possible diagnosis of diseases affecting glomeruli or vasculature or in cases of uncertain etiologies. The majority of AKI cases are diagnosed in the clinical context. The lack of specific therapeutic option coupled with risk of complications have also been a barrier for kidney biopsy in patients with AKI and thus, the value of histological features in predicting outcome has not been studied thoroughly.

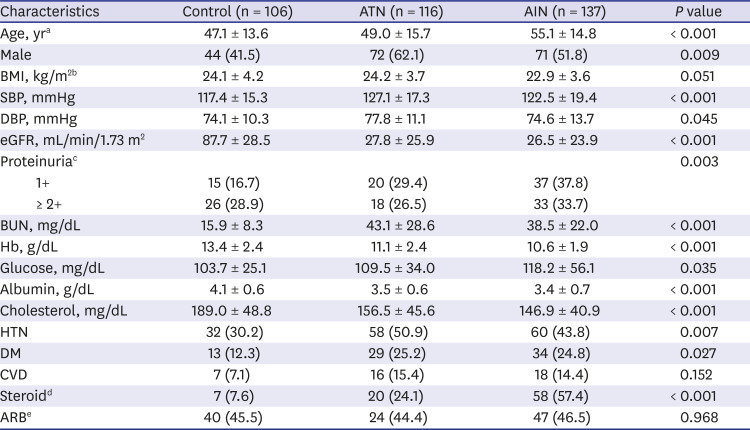

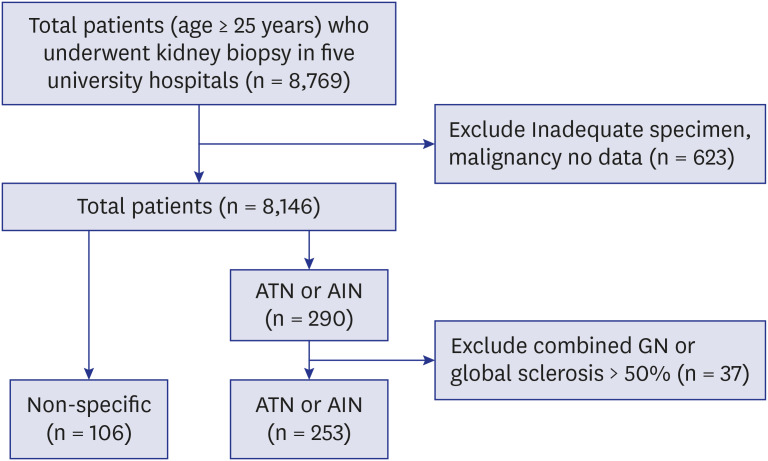

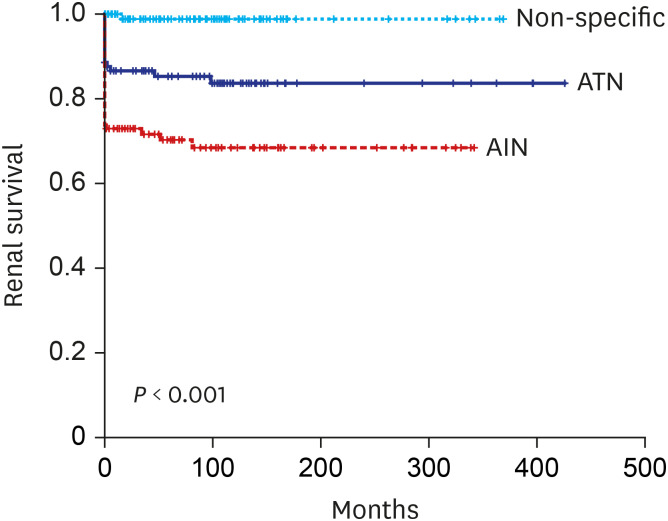

Here in this study, we compared long-term renal outcome of 116 biopsy proven ATN and 137 AIN cases. Rate of progression to ESRD during the mean follow up of 76.5 ± 91.9 months were compared and pathological features that are associated with progression to ESRD were also determined.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

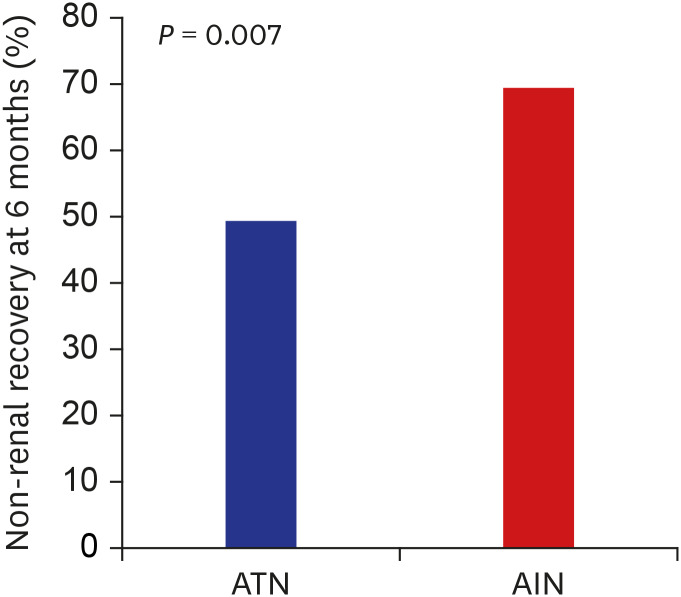

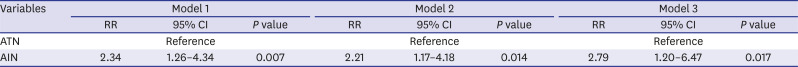

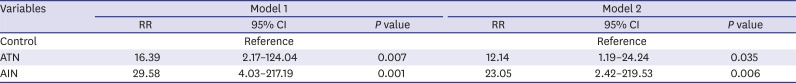

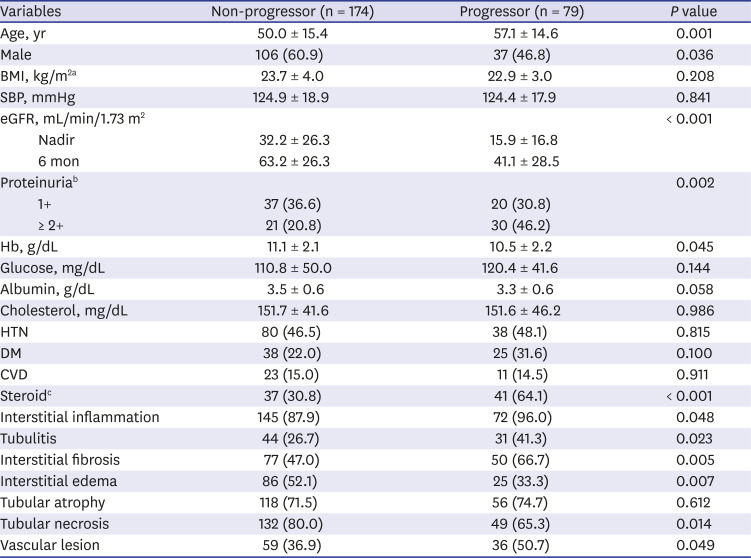

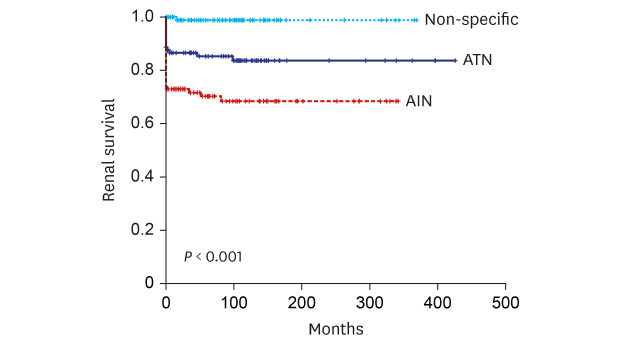

In this study, we demonstrated the followings; 1) substantial proportion of patients with biopsy proven ATN (21.5%) and AIN (39.4%) progressed to ESRD in long-term follow up, 2) AIN showed worse renal outcome compared to ATN, 3) older age, female sex and low nadir eGFR, 6 months eGFR were associated with ESRD progression, and 4) pathological features including interstitial inflammation, tubulitis, interstititial fibrosis and vascular lesion were also associated with progression to ESRD regardless of causes.

Although epidemiological studies have shown AKI increases the risk of CKD and/or ESRD, long-term renal outcome of AKI still remains unclear and lack of biopsy based studies in AKI might contribute to this uncertainty. ATN from ischemia, toxins or infection is the most common type of AKI and recently, AIN has become increasingly recognized as an important cause of AKI. However, the reported incidence of AIN was only 1%–4.7% in all kidney biopsy series

6 and 10%–27% in biopsies performed in patients with AKI.

11 Percentage of AIN of total 8,769 biopsies in our study (1.9%) was also comparable with previous report. The renal outcomes of AIN have been reported to be poor. In a single-center study of 133 patients with biopsy-proven AIN, 38% of patients achieved partial recovery while 14% showed no recovery at 6 months.

12 Another study of 157 patients with AIN also showed that 52.2% of patients developed CKD by 12 months and ESRD developed in 9.4% of steroid-treated patients and in 34.4% of non-treated patients during a median follow-up of 20 months.

713 In line with these studies, our study also demonstrated poor renal outcome; 69.4% of patients did not recover their renal function defined as eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 at 6 months and more importantly, we demonstrated that 39.4% of patients ultimately progressed to ESRD in a follow up period of 76.5 ± 91.9 months regardless of steroid treatment. Although specific etiologies of AIN are not separately analyzed in this study, we could clearly demonstrate worse renal outcome in patients with AIN in very long term follow up. RR of developing ESRD in AIN patients were 23-fold higher compared to control group. Significantly older age, more frequently combined interstitial fibrosis or vascular lesion, that are indices of chronicity, in AIN could be one factor facilitating the progressive CKD/ESRD. In contrast to AIN that the kidney biopsy is prerequisite for diagnosis, biopsy studies of ATN have been far more limited.

1415 The vast majority of ATN is diagnosed in the clinical context with a help of traditional urinary indices with reasonable degree of accuracy. ATN has been considered to have a relatively good prognosis in terms of functional recovery. However, according to a study by Abdulkader et al.

16 renal outcome of biopsy proven ATN also seems to poor. They demonstrated that 11 of 18 biopsy proven ATN patients showed only partial recovery of renal function and higher peak creatinine, longer hospital stay and tubulointerstitial lesion that was a sum of tubular necrosis, tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis and interstitial infiltrate were predictors of partial recovery. However the number of patients and follow up period were only 18 patients with 6 months, making a firm conclusion impossible.

17 Recently, a 6.64-fold increased risk of developing stage 4 CKD was observed in US veterans of more than 110,000 with ATN.

16 The annual incidence of ESRD attributed to ATN was estimated to be 3.5% in 2009–2010.

3 However, that study has possibility to have included patients with other causes of AKI, because the definition of ATN used in the study was based on laboratory findings and diagnostic code of acute renal failure or ATN only. In contrast, our study analyzed a relative large number of biopsy proven ATN patients (n = 116) with long term follow up to ESRD. In spite of lower rate of non-recovery or progression to ESRD compared to AIN, patients with biopsy proven ATN still showed poor renal outcome; 49.3% did not achieve renal functional recovery defined as eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 at 6 months and more importantly, 21.7% progressed to ESRD during 76.5 ± 91.9 months that is significantly higher compared to control group. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study of long-term renal outcome of histologically confirmed native kidney ATN. Although specific indication or timing of biopsy are not clearly recorded, these data could give an important message that ATN from diverse etiologies might be contributing to increasing incidence of ESRD worldwide. Even after adjusting multiple patient factors, RR of progressing to ESRD was 12.136-fold higher in biopsy proven ATN patients compared to control group. However, given that the majority of patients with AKI are diagnosed and treated without biopsy, we still cannot answer to questions that who and what percentage of patients progress to CKD/ESRD.

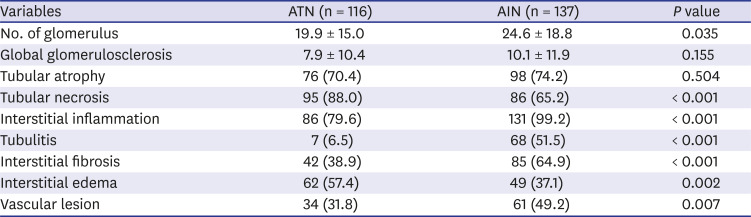

Kidney biopsy is an important tool in diagnosis and outcome prediction in glomerular diseases. Degree of interstitial fibrosis or number of crescents are well known histologic features in predicting outcome or treatment response. ATN and AIN are distinct pathological entities with predominant tubular necrosis and interstitial inflammation. However, pathological features including tubular necrosis, interstitial inflammation, edema, tubulitis and even chronicity indices such as tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis or vascular lesion are substantially overlapped in both entities. We assessed the value of these histological features in predicting renal outcome in both AIN and ATN. The presence of interstitial inflammation, tubulitis, interstitial fibrosis and vascular lesion in both ATN or AIN were significantly associated with progression to ESRD while tubular necrosis, interstitial edema or tubular atrophy were not. Although all these pathological features were not found to be an independent factor that can predict ESRD, the value of these pathological features in ATN or AIN as outcome predictors should be further assessed in larger series of native kidney biopsy studies. Given that insight regarding the role of kidney biopsy in AKI is expanding, it is possible that combining these pathological features with patient clinical and laboratory findings might improve the accuracy of outcome prediction. In addition, kidney biopsy in AKI may offer opportunities of finding newer insight into heterogenous pathogenesis, molecular mechanisms and newer therapeutic targets of human AKI.

Despite several meaningful findings, our study also has limitations First, kidney biopsies were not reviewed by same renal pathologist. Second, the indication and timing of biopsy might have differed among clinicians and third, the etiologies of ATN or AIN were not determined. Finally, we included relatively severe AKI and this result could not be generalized to the patients with mild degree of ATN or AIN.

However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to show very long-term renal outcome of biopsy proven ATN and AIN and also suggest the possible usefulness of pathological findings in predicting outcome.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated patients with biopsy proven AIN or ATN are at high risk of developing ESRD compared to control patients. Pathological features of interstitial inflammation, tubulitis, interstitial fibrosis or vascular lesion might be important in progression.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download