Abstract

With the epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2, the number of infected patients was rapidly increasing in Daegu, Korea. With a maximum of 741 new patients per day in the city as of February 29, 2020, hospital-bed shortage was a great challenge to the local healthcare system. We developed and applied a remote brief severity scoring system, administered by telephone for assigning priority for hospitalization and arranging for facility isolation (“therapeutic living centers”) for the patients starting on February 29, 2020. Fifteen centers were operated for the 3,033 admissions to the COVID-19 therapeutic living centers. Only 81 cases (2.67%) were transferred to hospitals after facility isolation. We think that this brief severity scoring system for COVID-19 worked safely to solve the hospital-bed shortage. Telephone scoring of the severity of disease and therapeutic living centers could be very useful in overcoming the shortage of hospital-beds that occurs during outbreaks of infectious diseases.

Graphical Abstract

The epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus started at the end of 2019.1 In a typical case of COVID-19, a high fever appears after a dry cough,2 in some cases, viral pneumonia develops and progresses resulting in shortness of breath.234 COVID-19 infection has a spectrum of severity.4

In our experience, in a considerable number of patients, the symptoms can deteriorate rapidly. Cases with severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome may have begun with mild symptoms for 7–8 days which suddenly deteriorated until they eventually required advanced life support.5

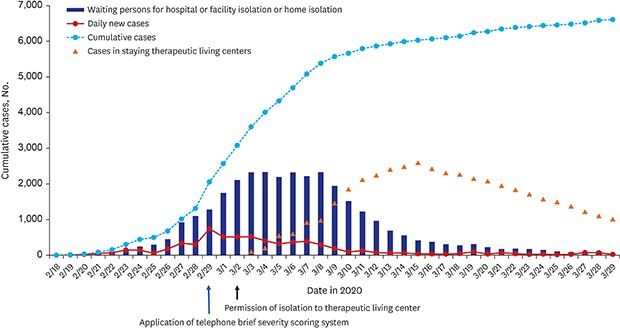

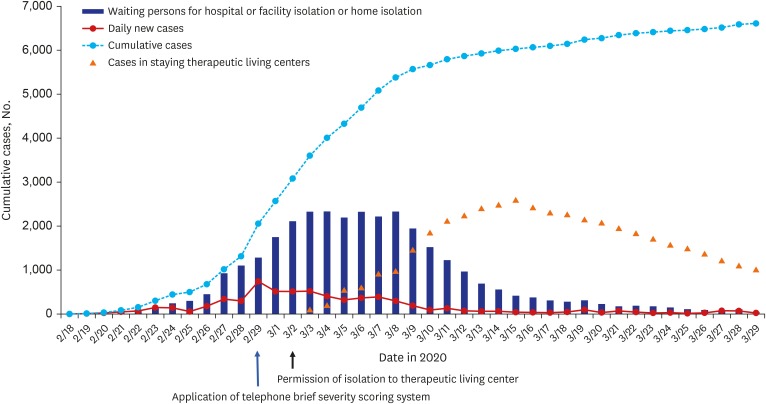

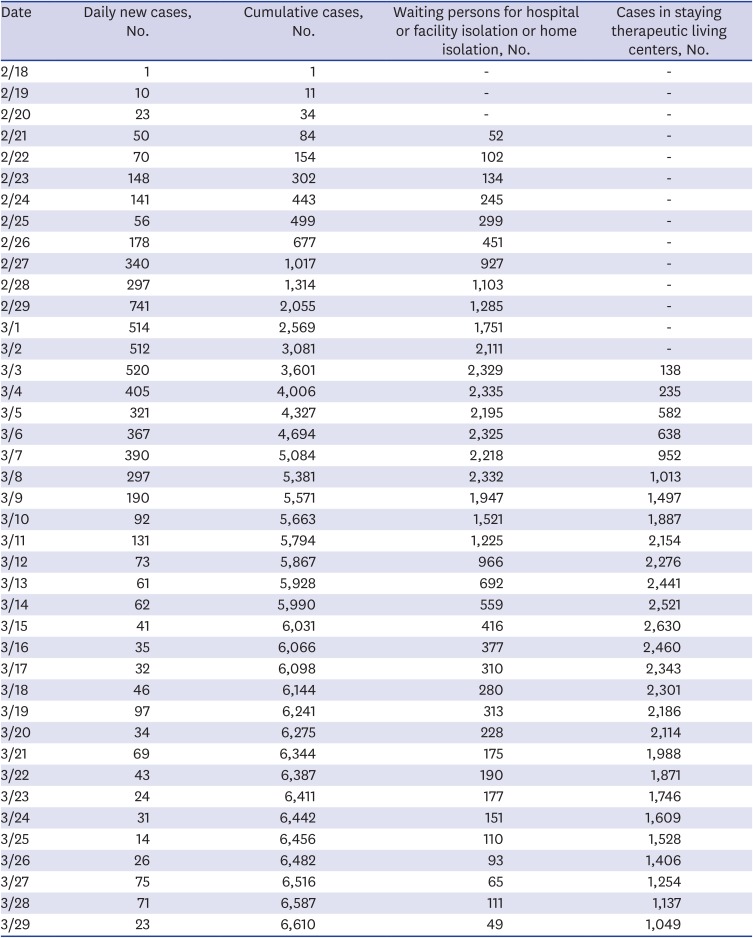

A patient diagnosed with polymerase chain reaction-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection was reported on February 18, 2020, in Daegu. There was an explosive increase in the number of COVID-19 patients in late February which made Daegu, the center of the outbreak in Korea. By February 29 the daily new patient count in Daegu had reached 741 and thousands waited for hospital beds as cases surged (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Three patients died at home during waiting for hospitalization on February 27, 28, and March 1.

The prevention guidelines for epidemic infectious diseases in Korea only allowed hospitalization of patients and had no criteria for prioritization rule in the situation of hospital-bed shortage. Only healthcare facilities were allowed to carry out isolation during epidemics.6

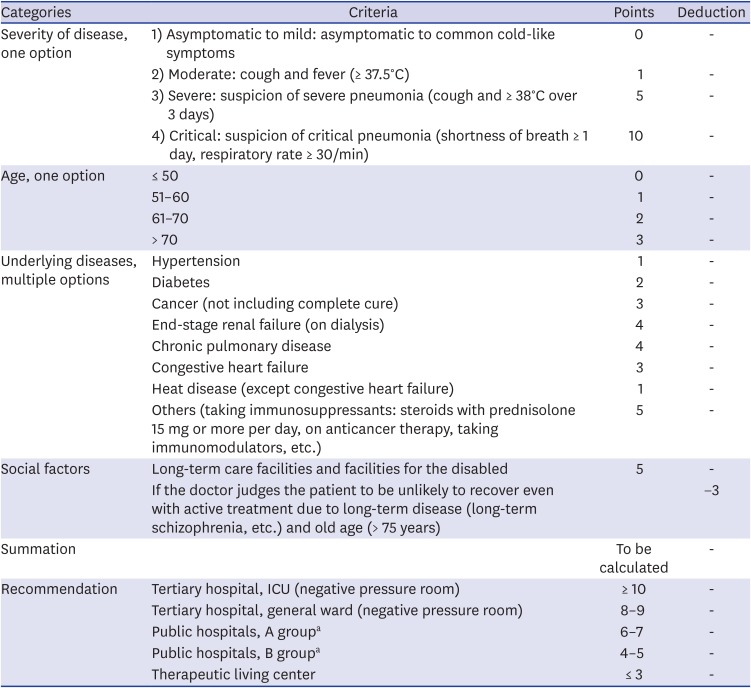

An empirical guideline was very in need to reduce the mortality rate of the population in the emergent situation in Daegu, Korea. We developed a brief severity scoring system for COVID-19 confirmed patients which can be used for assessing the severity of patients by telephone communication (Table 2). We selected and weighed the variables of the Telephone Severity Scoring System considering of the previous reports about the clinical characteristics and risk factors of mortality of COVID-19.478

This system aimed to give priority to hospitalization for severely ill patients and we began using this system on February 29 2020 (Fig. 1). This scoring system is composed of items indicating age, the severity of the disease, underlying diseases, and social factors and each item has a different weight (Table 2).

Daegu local authority asked the government to change the rules for isolation options to include facility isolation because there was an urgent need for a solution to the hospital-bed shortage. Facility isolation centers for patients who were waiting at home were prepared while waiting for approval for the facility isolation option and this was included in the revised government guidelines on March 2, 2020. Health officials of government labeled “therapeutic living centers” for the isolation facility.

Asymptomatic to mild cases of COVID-19 were considered suitable for the therapeutic living centers. Moderate severity patients were deemed suitable for the community hospital (group A and B, A is more severe than B). Severe pneumonia patients were to be admitted to a tertiary care hospital. It was necessary to determine the appropriate hospitalization option by doctors recording the symptoms of a person over the telephone without seeing the patient with COVID-19.

For admitted patients with COVID-19, the 3 stages (mild, severe, and critical) were used in some papers.37 The National Early Warning Score (NEWS) and modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) system for acutely ill patients was composed of 4 stages.910 However NEWS and MEWS are for hospitalized patients and not for patients waiting at home to be admitted and they are not specific for COVID-19 patients. COVID-19 had shown different clinical features and acute exacerbation reported frequently.1112 And, age factor seemed relatively more important in COVID-19 than other acute infectious diseases.4

We classified waiting COVID-19 patients into 4 categories; asymptomatic to mild, moderate, severe and critical (Table 2); 1) Asymptomatic to mild patients may be asymptomatic or have common cold-like symptoms, 2) Moderate patients have a cough and fever (≥ 37.5°C), 3) Severe patients have suspected severe pneumonia, that is, a cough and ≥ 38°C fever lasting over 3 days and, 4) Critical patients have suspected critical pneumonia if they have had shortness of breath for over 1 day and a respiratory rate of 30/min or over. Pilot test was performed with this Telephone Severity Scoring System for 3 patients before implementation of the scoring to the patients. About 150 doctors from the Daegu Medical Association participated voluntarily and checked the status of patients who were staying at home every day without any payments. They reported the interview results to the team arranging hospitalization or facility isolation in Daegu City.

Patients with asymptomatic to mild severity were suitable for the therapeutic living centers, however, we were initially worried about possible aggravation of the severity after the facility isolation. Fifteen therapeutic living centers were operated with 3,033 admissions from March 3, 2020, to March 26, 2020. Only 81 cases (2.67%) were transferred to the hospital after the facility isolation. Mean and median time of transfer from therapeutic isolation centers to hospitals were 6.7 days and 4.0 days, respectively (range, 0–22 days). The main reasons of transfer to hospitals included acute exacerbation after facility isolation (49/81, 60.5%), anxiety and depressive mood (16.0%) and missed underlying medical conditions (7.4%).

We found that the brief severity scoring system for COVID-19 worked safely to solve the hospital-bed shortage.

After implementing the brief severity scoring system for COVID-19 for the classification of patients for priority of hospitalization, we noted a decline in waiting patients (Fig. 1), furthermore, no patient died at home while waiting for hospitalization and facility isolation.

To our knowledge, based on a literature review, there is no previous report of this kind of approach for the overcoming of bed shortages during an epidemic. The Wall Street Journal reported that this approach in Daegu played a major role in overcoming the problem of hospital-bed shortage.

We think this brief severity scoring system for COVID-19 patients is the first to be developed and successfully introduced while facing an explosive outbreak. It proved to have a significant impact on solving the acute hospital-bed shortage. The scoring of disease severity by telephone interview has limitations to the accuracy of the assessment of patients. However, there are no alternatives for severity assessment in the middle of a highly infectious epidemic.

In conclusion, based on our experience, this type of remote telephone scoring of disease severity can be very useful in overcoming shortages of hospital-beds during an outbreak of infectious diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you for the all the volunteer doctors of Daegu Medical Association for the interviewing and counselling for the COVID-19 patients in Daegu, Korea.

References

1. Munster VJ, Koopmans M, van Doremalen N, van Riel D, de Wit E. A novel coronavirus emerging in China - Key questions for impact assessment. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(8):692–694. PMID: 31978293.

2. Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(10):929–936. PMID: 32004427.

3. Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020; 41(2):145–151. PMID: 32064853.

4. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020.

5. Heymann DL, Shindo N. WHO Scientific and Technical Advisory Group for Infectious Hazards. COVID-19: what is next for public health? Lancet. 2020; 395(10224):542–545. PMID: 32061313.

6. Huh K, Shin HS, Peck KR. Emergent strategies for the next phase of COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020; 52(1):105–109. PMID: 32100487.

7. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020; 395(10229):1054–1062. PMID: 32171076.

8. Korean Society of Infectious Diseases and Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Analysis on 54 mortality cases of coronavirus disease 2019 in the Republic of Korea from January 19 to March 10, 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(12):e132. PMID: 32233161.

9. Silcock DJ, Corfield AR, Gowens PA, Rooney KD. Validation of the National Early Warning Score in the prehospital setting. Resuscitation. 2015; 89:31–35. PMID: 25583148.

10. Subbe CP, Kruger M, Rutherford P, Gemmel L. Validation of a modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. QJM. 2001; 94(10):521–526. PMID: 11588210.

11. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020; 395(10223):497–506. PMID: 31986264.

12. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020.

Fig. 1

Trend of daily and cumulative COVID-19 confirmed patients in Daegu, patients waiting for hospitalization or facility isolation or home isolation and admission to the facility isolation (From 2/18/2020 to 3/29/2020).

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Table 1

Numbers of daily and cumulative coronavirus disease 2019 confirmed patients in Daegu, patients waiting for hospitalization, facility isolation or home isolation and staying in therapeutic living centers between 2/18/2020 and 3/29/2020

Table 2

Brief severity scoring criteria for prioritization for hospitalization or admission to the therapeutic living centers

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download