This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

Nonpharmaceutical intervention strategy is significantly important to mitigate the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) spread. One of the interventions implemented by the government is a school closure. The Ministry of Education decided to postpone the school opening from March 2 to April 6 to minimize epidemic size. We aimed to quantify the school closure effect on the COVID-19 epidemic.

Methods

The potential effects of school opening were measured using a mathematical model considering two age groups: children (aged 19 years and younger) and adults (aged over 19). Based on susceptible-exposed-infectious-recovered model, isolation and behavior-changed susceptible individuals are additionally considered. The transmission parameters were estimated from the laboratory confirmed data reported by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from February 16 to March 22. The model was extended with estimated parameters and estimated the expected number of confirmed cases as the transmission rate increased after school opening.

Results

Assuming the transmission rate between children group would be increasing 10 fold after the schools open, approximately additional 60 cases are expected to occur from March 2 to March 9, and approximately additional 100 children cases are expected from March 9 to March 23. After March 23, the number of expected cases for children is 28.4 for 7 days and 33.6 for 14 days.

Conclusion

The simulation results show that the government could reduce at least 200 cases, with two announcements by the Ministry of education. After March 23, although the possibility of massive transmission in the children's age group is lower, group transmission is possible to occur.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mathematical Modeling, Behavior Changes, School Opening Delay, School Closures

INTRODUCTION

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Korea was reported on January 20, 2020, who entered Korea from Wuhan, China.

1 Through the intensive contact tracing of the cases by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC), the locally transmitted cases were isolated immediately to prevent community transmission. On February 16, the first case without epidemiologic link was reported, and the authorities concerned the community transmission of the disease.

1 From mid-February, the number of COVID-19 cases has exploded. The KCDC had raised the COVID-19 alert level to the highest from orange to red on February 23, 2020.

1 The government strengthened the overall nonpharmaceutical intervention measures because antiviral agents and vaccines were not developed. The government screened high-risk groups which had close contact with confirmed cases and recommended minimizing social gathering and outdoor activities to the public. School closures were also one of the nonpharmaceutical intervention strategies to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

Since the epidemic was expected to continue in March, the public concerned about the possibility of massively increased cases in school-aged children who have high close contacts among them. The Ministry of Education decided to delay school-opening by 7 days from March 2 to March 9 to reduce the risk of infection among school children on February 23.

1 On March 2, it was announced that the opening of schools would be further postponed for an additional 14 days from March 9.

1 As COVID-19 epidemic continues, an additional 14-day-delay from March 23 was announced on March 17.

2

There is a controversial issue between a possibility of a massive outbreak and education for children. In this study, it is aimed to quantify the potential effects of delay of school opening as the epidemic progressed through mathematical modeling. We investigate the potential effect as the child-to-child transmission increased after the school opening. The expected number of cases to occur when the school was opened as scheduled without delaying the school opening is calculated.

METHODS

Data

The daily cumulative confirmed data was retrieved from the KCDC Press release.

2 The aged registered population number in February 2020 from Statistic Korea was used as the total population data.

3 All data that we used in this work are open to the public.

Mathematical model

Mathematical modeling is a beneficial tool to describe transmission dynamics of infectious diseases. The A/H1N1 influenza spread in U.S. was predicted using susceptible-infectious-recovered model.

4 The mathematical model for 2009 A/H1N1 influenza in Korea was developed and predicted cases using the reported data.

5 Recently, the COVID-19 epidemic has been studying by many researchers.

678

A mathematical model is developed based on susceptible-exposed-infectious-recovered (SEIR) model to describe the COVID-19 transmission dynamic in Korea. We consider the first community transmitted case is the patient No. 29, and the simulation period is starting from February 16, which is the confirmed date of the patient.

1 It is of note that the first 28 cases are not considered in this study.

Because most COVID-19 patients are isolated after the laboratory confirmation, the isolated (

Q) compartment is added in the model. As an epidemic progressed, the government reinforced social distancing control. Moreover, people changed their behaviors such as avoiding close contacts or enhancing personal hygiene. In this work, it is assumed that the general susceptible group (

S) is transferred to the behavior-changed susceptible group (

SF), which is less likely to be transmitted the disease through social distancing.

9

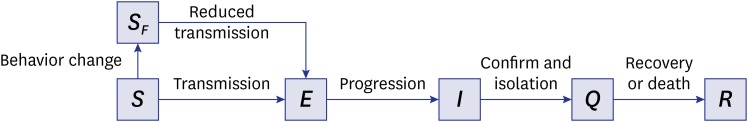

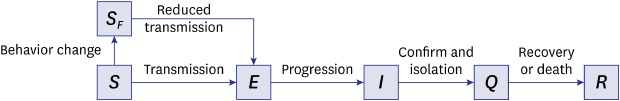

Fig. 1 describes the flow diagram of COVID-19 transmission dynamics considering behavior change of susceptible population.

Fig. 1

Flow diagram of coronavirus disease 2019 transmission dynamics.

S = susceptible individuals, SF = behavior-changed susceptible individuals, E = exposed individuals, I = infectious individuals, Q = confirmed and isolated individuals, R = removed individuals.

Susceptible individuals (

S,

SF) are exposed to the virus via close contact with infectious individuals (

I). Exposed individuals (

E) are moved to the infectious group (

I) after the incubation period. The infectious individuals (

I) are confirmed and isolated (

Q), and finally, they are removed (

R) from the dynamics. The transmission rate of behavior-changed susceptible individuals (

SF) is reduced by a parameter

δ through social distancing and personal hygiene enhancement. The parameter

δ is assumed as 1/50 because there is no experimental study yet. The mean incubation period of the virus is set to 4.1 days, referring to the KCDC briefing on February 16.

10 The mean period from symptom onset to confirmation and isolation is considered as four days.

11 The mean period from confirmation to recovery is calculated as 14 days, which is the average of 16 patients from confirmation to discharge. Mortality rate is not considered in this model because it is difficult to calculate precisely at this time. The mathematical model composed by ordinary differential equations and parameter description are provided in

Supplementary Data 1 and

Supplementary Table 1.

For each epidemiological status, two age groups are considered; aged 19 years and younger (children) and aged over 19 (adults). In Korea, more than 75% of preschool children go to daycare center or kindergarten

1213 and approximately 95% of school-aged children go to school.

141516 Thus, it is reasonably assumed that the children age under 20 have homogeneous transmission and the effect of school opening. The epidemiological factors except for the contact rates such as behavior change rate, incubation period, and recovery rates are assumed to be the same with respect to the age groups. In the model, the different contact rate is embedded in the transmission matrix

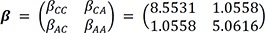

β=(βCCβCAβACβAA)

. Since two age groups are considered, four transmission rates in the transmission matrix (

β) are needed to estimate: within children (

βCC), to children from adults (

βCA), to adults from children (

βAC), and within adults (

βAA). Assuming the same transmissibility and susceptibility of two groups, the transmission matrix is symmetric; the transmission rate to children from adults and that to adults from children are the same (

βCA =

βAC).

Numerical simulation

All numerical simulations were performed using Matlab R2018b developed by MathWorks.

17 The least squares fitting optimization tool,

lsqcurvefit, was used to estimate the best-fitted transmission rates.

RESULTS

School opening delay I: from March 2 to March 9

The transmission matrix by age group is estimated using the data reported from February 16 to March 2.

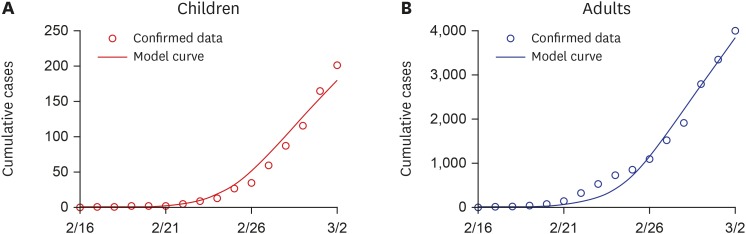

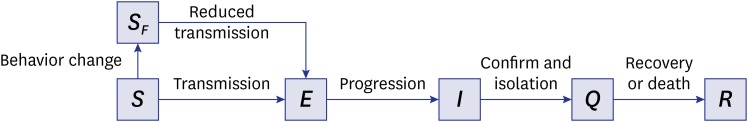

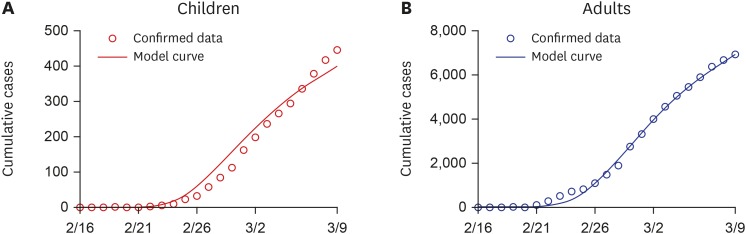

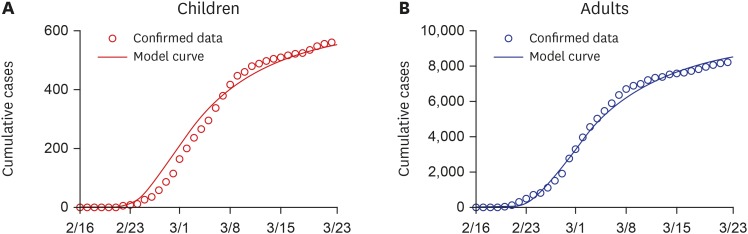

Fig. 2 shows the circles as cumulative confirmed cases for children (left) and adults (right) and the corresponding model curves (solid line).

Fig. 2

Best datafit results from February 16 to March 2. Circles indicate the daily reported confirmed data from Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention press and solid curves display the model curve using estimated parameters. (A) Children. (B) Adults.

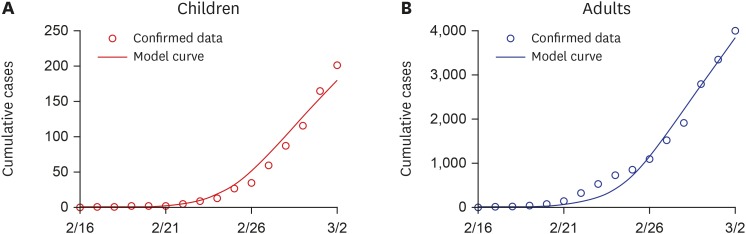

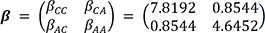

The estimated transmission matrix is as follows:

The larger values of diagonal components indicate that the transmission rate of intra-groups is larger than inter-groups (βCC, βAA > βCA = βAC). The higher transmission rate among children (βCC) is reflected by a higher contact rate among children. Using the estimated transmission matrix, it was calculated how much the number of school-aged patients would be increased after 7 days from March 2 to March 9, assuming that the transmission rate between children is increased when the schools open.

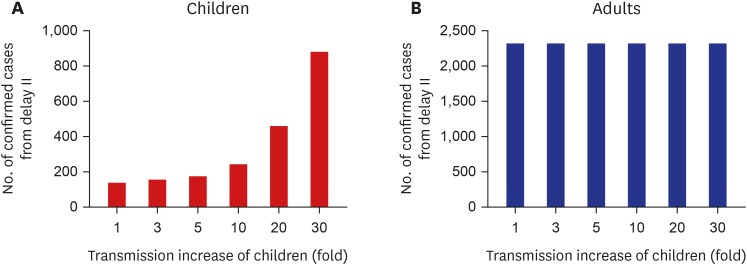

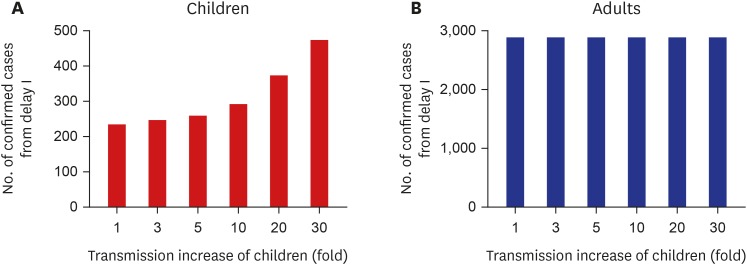

Fig. 3 displays the expected number of confirmed cases with respect to the incresased transmission rate among children when schools open.

Fig. 3A depicts the expected number of children while

Fig. 3B shows the number of adults. The first bar in each frame indicates the expected number of confirmed cases for 7 days without an increase of transmission rate when school opening. It also can be interpreted as the expected number of confirmed cases from March 2 to March 9 in the mathematical model. The model predicted cases in children and adult groups are 238.1 and 3,023, respectively. It is of note that 246 children and 3,170 adult cases are actually confirmed during this period (March 2 to March 9) in reported data; reported pediatric cases are increased from 201 to 447 cases, while reported adults cases are increased from 4,011 to 6,935.

2 This shows that mathematical model could predict the number of cases well.

Fig. 3

Expected number of confirmed cases from March 2 to March 9. (A) Children. (B) Adults.

Assuming that transmission rate was increased 10 fold after schools open, approximately 60 cases would be expected to occur more, and it means more than eight cases could be additionally confirmed every day from March 2 to March 9. If the transmission rate was increased 30 fold after school opening, the expected cases could be doubled.

School opening delay II: from March 9 to March 23

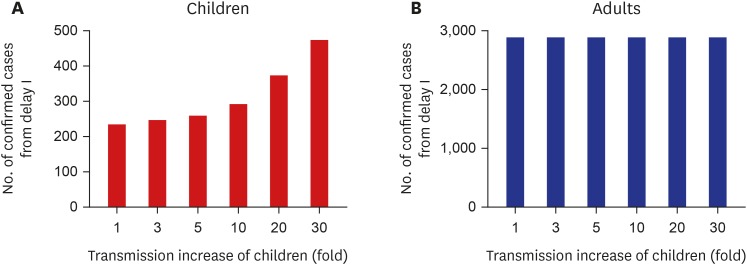

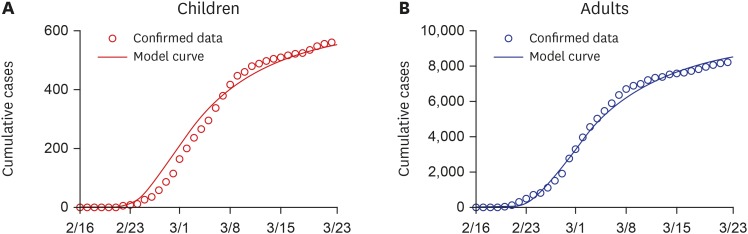

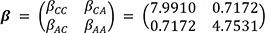

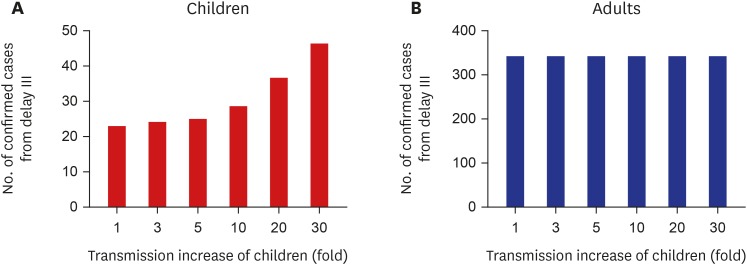

Fig. 4 shows the cumulative confirmed cases (circles) for children (left) and adults (right) and the corresponding model curves (solid lines) from February 16 to March 9.

Fig. 4

Best datafit results from February 16 to March 9. Circles indicate the daily reported confirmed data from Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention press and solid curves display the model curve using estimated parameters. (A) Children. (B) Adults.

The estimated transmission matrix is as follows:

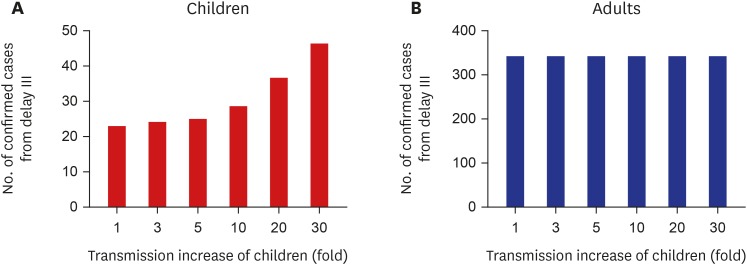

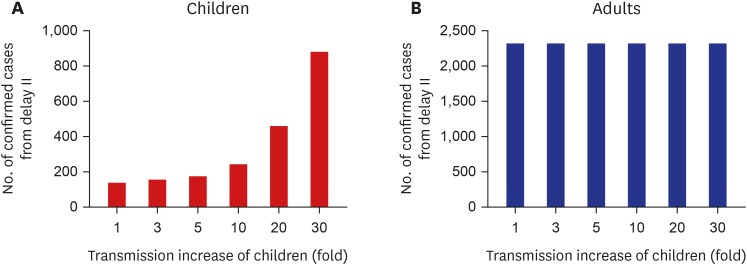

Left and right frames of

Fig. 5 show the expected numbers of children and adults as the transmission rate is increased due to school opening, respectively. The first bar in each frame indicates the expected number of confirmed cases for 14 days without an increase of transmission rate with school opening delay.

Fig. 5

Expected number of confirmed cases from March 9 to March 23. (A) Children. (B) Adults.

From March 2 to March 9, 238.1 children and 3,023 adult cases are expected to occur for 7 days while 137.6 children and 2,354 adult cases are expected for 14 days. As most susceptible individuals were aware of the epidemic and they changed the behavior, fewer cases are predicted. As of March 22, 114 children and 954 adults were actually reported, which is lower than the model prediction.

If the transmission rate was increased 10 fold for 14 days after school opening on March 9, approximately 100 cases are expected to occur more. If the transmission rate was increased 30 fold, the number of expected cases for children would be increased to 886.9 children until March 23. As the expected children cases are significantly increased with high child-to-child transmission rates, it is expected that the adult cases are also increased to 2,363 although no transmission increase between children and adults and among adult groups are assumed.

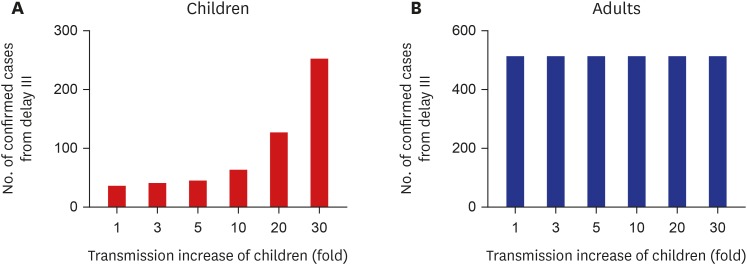

School opening delay III: from March 23 to April 6

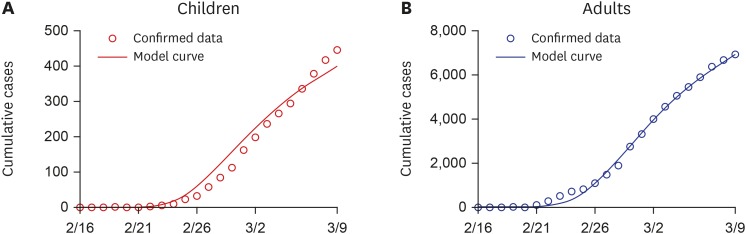

The transmission matrix by age group was estimated using the data reported from February 16 to March 22, and the model is extended to March 23.

Fig. 6 displays the reported confirmed data and extended model curve. The number of reported cases seems to be stabilized. It is because the screening of high-risk groups is finished, and the government highly recommended the public to conduct social distancing. It leads to an increase in the rate of behavior change.

Fig. 6

Best datafit results from February 16 to March 22 and its extension until March 23. Circles indicate the daily reported confirmed data from Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention press and solid curves display the model curve using estimated parameters. (A) Children. (B) Adults.

The estimated transmission matrix is as follows:

It may show the transmission rates are increased, but the effective transmission rate is decreased as the transmission rate of behavior change is increased double.

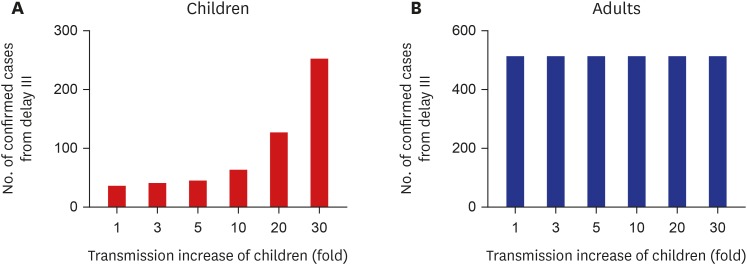

Figs. 7 and

8 show the expected number of confirmed cases for 7 days and 14 days, respectively, after March 23. If the transmission rate will be increased 10 fold after school opening, the number of expected cases for children is increased to 28.4 for 7 days and 33.6 for 14 days. If the transmission rate is increased 30 fold, the pediatric patients will be increased rapidly from March 30 to April 6. For 7 days, 46.4 cases are expected to occur while 255.8 cases are expected to occur for 14 days.

Fig. 7

Expected number of confirmed cases for 7 days after March 23. (A) Children. (B) Adults.

Fig. 8

Expected number of confirmed cases for 14 days after March 23. (A) Children. (B) Adults.

DISCUSSION

We developed an age-structured SEIR model including with quarantine and behavior-changed susceptible groups, in order to investigate the effect of school opening delay on the COVID-19 epidemics. Simulation results showed that the government could reduce at least 200 cases and 900 cases assuming 10 fold and 30 fold increased transmission rates, respectively, with two announcements by the Ministry of Education on Feburary 23 and March 2, 2020. Furthermore, the extended school closure from March 23, 2020 for two more weeks could reduce the magnitude of cases and speed up the end of epidemic; if the transmission rate will be increased 10 fold or 30 fold after school opening, the number of expected cases for children is, respectively, increased to approximately 33 or 255 cases for 14 days.

According to the KCDC Press release, 80.9% of the total confirmed cases are related to the clustered outbreak as of March 22. Most massive outbreaks have occurred in religious facilities and working spaces with highly close contacts. School is one of the places with close contact occurrence. The school closure is widely used as a nonpharmaceutical strategy to mitigate the disease spread. During 2009 influenza epidemic in Hong Kong province, it was estimated that intra-children transmission rate for the 3–12 age group was reduced by 86% (44%–99%) via primary school and kindergarten closure.

18 The students in Korea are spending a long time in school than the students in any other country. After school opening, the student will also spend more time in after-school private educational institutes. The increment of transmission among children will be significantly higher.

Due to the screening of close contact group and quarantine strategy by the government and public cooperation of social distancing, the daily new cases have been decreasing. The case reduction effect from March 23 to April is lower than the school opening delay policy announced before. However, there are still clustered cases in a specific group with close contact.

This study has some limitations. The parameters related to behavior changes are assumed. If the experimental study is published, the reliability of prediction would be increased. In addition, the school opening effect is relatively underestimated. In this study, it is assumed that after school opening, only the transmission rate among children's age groups is increased. Other transmission rates will not increase and all behavior-changed susceptible individuals are keeping their transmission reduction efforts such as wearing the mask and enhanced personal hygiene. In reality, other transmission risk factors could be increased after school opening. At first, it is possible to increase the contact rate between children and teachers and the contact rate within teachers. It is hard for children to keep their personal hygiene level when they go to school. Young age group is not enough to be aware of the COVID-19 epidemic and furthermore, the teachers can loosen their guidance to all children in the class. After one child is confirmed, transmission from child to child within the classroom will rapidly proceed. Although a different respiratory virus, in the U.S. study, respiratory syncytial virus was spread to 50% of the classmates after the first case diagnosed by day 6 at a day care.

19

The increase in the number of children after school starts is likely to lead to the spread of the virus to parents, grandparents, and other adults around the children. An increase in incidence in the elderly age group is at risk of leading to an increase in mortality.

In conclusion, simulation study though mathematical model showed that school closure is an essential nonpharmacological intervention to prevent or mitigate the COVID-19 epidemic. Especially the third announcement of school opening delay on March 23 for two more weeks could reduce the number of expected cases for children at least 255 assuming the 30 fold increased transmission rate among students.

In Korea, one of the critical factors that the confirmed cases are rapidly reduced is behavior changes of susceptible population such as social distancing. After school opening in April, keeping social distancing is important to prevent the reoccurrence of epidemic. Therefore, the government needs to establish an achievable and practical social distancing policy and preventive measures against epidemics.

. Since two age groups are considered, four transmission rates in the transmission matrix (β) are needed to estimate: within children (βCC), to children from adults (βCA), to adults from children (βAC), and within adults (βAA). Assuming the same transmissibility and susceptibility of two groups, the transmission matrix is symmetric; the transmission rate to children from adults and that to adults from children are the same (βCA = βAC).

. Since two age groups are considered, four transmission rates in the transmission matrix (β) are needed to estimate: within children (βCC), to children from adults (βCA), to adults from children (βAC), and within adults (βAA). Assuming the same transmissibility and susceptibility of two groups, the transmission matrix is symmetric; the transmission rate to children from adults and that to adults from children are the same (βCA = βAC).

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download