INTRODUCTION

Vital signs are literal indicators of vitality. They are used in cardiopulmonary resuscitation guidelines such as pediatric advanced life support,

12 early detection systems for deteriorated patient such as pediatric early warning system,

34 and triage systems in emergency department (ED) such as Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS).

56 CTAS is one of the most widely used triage systems in the world, and CTAS-based triage system is used in many countries including Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Costa Rica, Hungary, etc.

67 In Korea, CTAS-based Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS) has been developed and is being used for triage in all emergency medical institutions nationwide since 2016.

8 CTAS was first implemented in 1999, and pediatric CTAS (PedCTAS) was developed in 2001 and has been periodically revised.

569 From the revised version of PedCTAS in 2008, the concept of triage modifiers was introduced, including heart rate and respiratory rate.

5 For example, even if the main symptom is the same, such as respiratory distress, the triage level is divided into level 1 (severe respiratory distress), level 2 (moderate respiratory distress), and level 3 (mild respiratory distress) according to how much the respiratory rate deviates from the age-specific normal range.

Abnormal heart rate or respiratory rate may be the only early sign of sepsis or shock,

5 which is in full agreement with the intent that severity may increase with heart rate and respiratory rate. However, if the vital signs were measured in a state that did not accurately reflect the patient's medical condition (such as in an upset state), and if they were used without knowledge or by some other intention, incorrect triage levels could be obtained.

57 It is well known that accurate triage according to the patient's medical urgency and timely input of medical resources is very important for improving patient safety and quality of the medical system.

10 Therefore, it is very important to measure vital signs and use them in the triage process when the patient is sufficiently stable. However, the size of the misclassification associated with vital signs can be large in children, thus care should be taken. A study on Japanese Triage and Acuity Scale, another CTAS-based triage system reported that 54.1% of children were triage modified due to abnormal vital signs.

7 And another simulation study of pediatric KTAS (PedKTAS) reported that 71.9% of patients were able to triage modification.

8

In this regard, the PedCTAS guideline states that the vital signs measured in a state of being temporarily tense or upset should not be used, and vital signs during a state of restfulness should be used.

56 However, there are several difficulties in applying this to clinical practice. First, it is doubtful whether it is possible to measure vital signs in a sick child during a restful state in an unfamiliar pediatric ED environment. It is also unclear whether the elevated heart rate or respiratory rate measured in a febrile patient should be determined to be elevated. In addition, each triage provider may have different subjective criteria for determining whether the patient is upset or stable, and the decision to whether or not to apply a slightly upset vital sign to the triage process may have inter-rater variation, depending on the situation.

The goal of this study was to analyze the possible degree of discrepancy in triage modification depending on possible subjective conditions, under the hypothesis that the decision to use abnormal vital signs for triage modification will vary not only with the patient's medical condition such as mental status of patient, but also according to the triage provider's position such as profession.

Go to :

METHODS

Data source

This study is an observational cross-sectional study. The data used in this study was provided by the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS). NEDIS was created in 2003 as the national network of emergency medical services in Korea. As of 2016, all of the 31 district emergency medical centers (EMCs), 120 regional EMCs, and 257 (98.1%) of the 262 regional emergency medical departments have been participating and transmitting data real time to NEDIS.

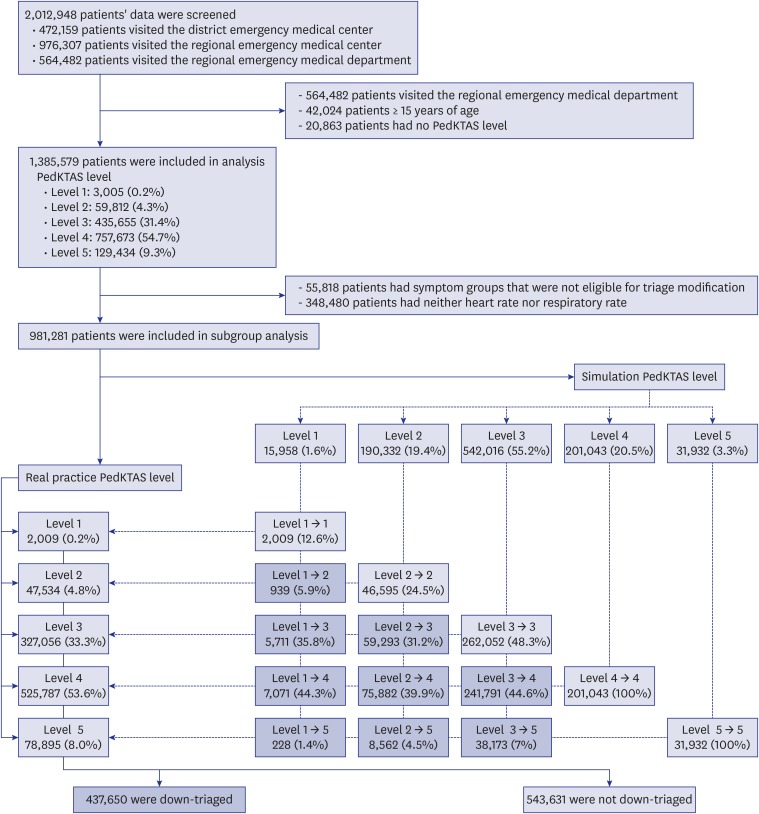

Participants

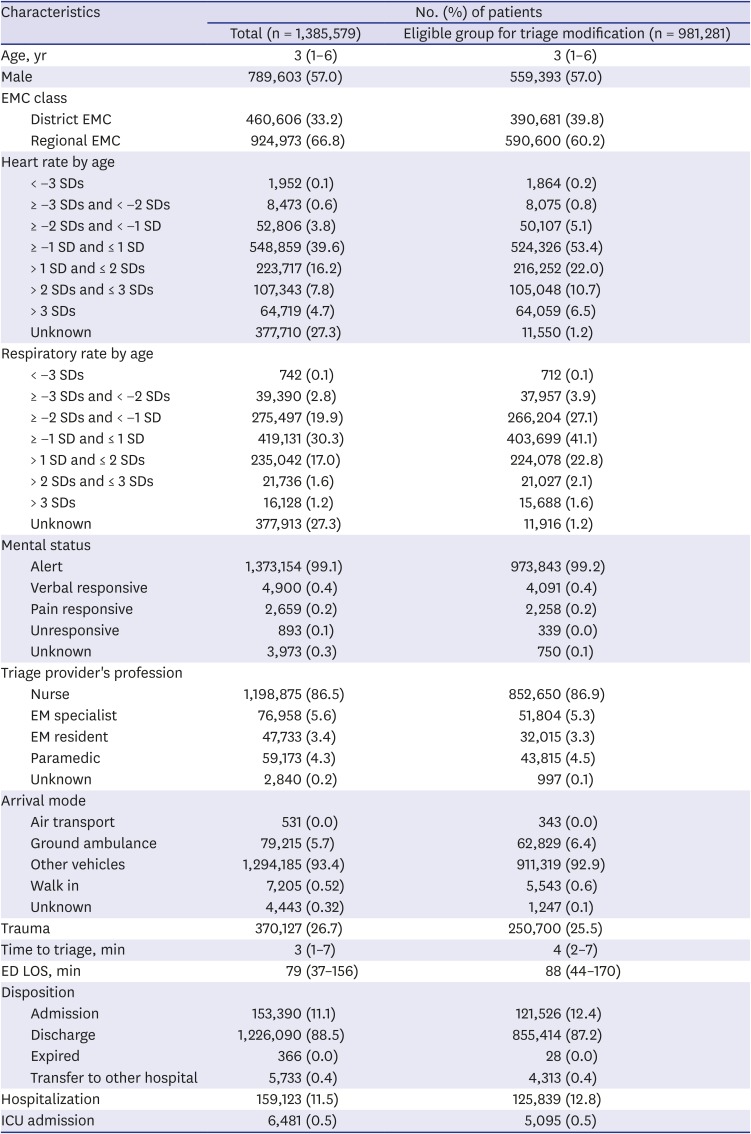

From January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2016, data from one year was provided by NEDIS. Patients under the age of 15 who were triaged using PedKTAS were included. Data from regional emergency medical departments that did not include vital signs were not transmitted to NEDIS, therefore excluded from the analysis. Cases that did not receive PedKTAS classification were also excluded from the analysis because these patients were most likely visiting the ED for purposes other than medical treatment such as issuing documents.

Data collection and processing

Data such as age, sex, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, PedKTAS level, PedKTAS classification code, mental status, ED length of stay, ED disposition, EMC class, profession of triage provider, arrival mode were collected and used for analysis. Hospitalization was defined to include cases admitted directly to the general ward, the intensive care unit (ICU), the operation room, as well as cases where patients were transferred to another hospital for admission. ICU admission was defined as cases admitted directly from the ED to the ICU, to the ICU through the operation room, and cases transferred to another hospital for ICU admission.

The patient's PedKTAS classification code was used to determine whether triage modification was possible. When triage modification was possible, triage level was calculated by applying measured vital signs. This process was carried out according to the method presented in the participant's manual of the CTAS.

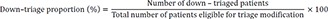

11 The PedKTAS level obtained by the above method was defined as simulation PedKTAS (S-PedKTAS) level. On the other hand, the actual triaged level was defined as real practice PedKTAS (RP-PedKTAS) level. Down-triage was defined as cases where the severity level of RP-PedKTAS was lower than the S-PedKTAS level (i.e., the number of RP-PedKTAS levels was higher than the number of S-PedKTAS levels), as it corresponded to a group eligible for triage modification. The formula for the down-triage proportion was:

Outcomes

The primary outcome was to observe whether there was a discrepancy in down-triage proportion depending on the profession of the triage provider, which is not related to the patient's medical condition. Secondary outcomes were differences in down-triage proportions depending on conditions such as the patient's mental status, arrival mode, presence of trauma, and EMC class, related to the patient's medical condition.

Statistical analysis

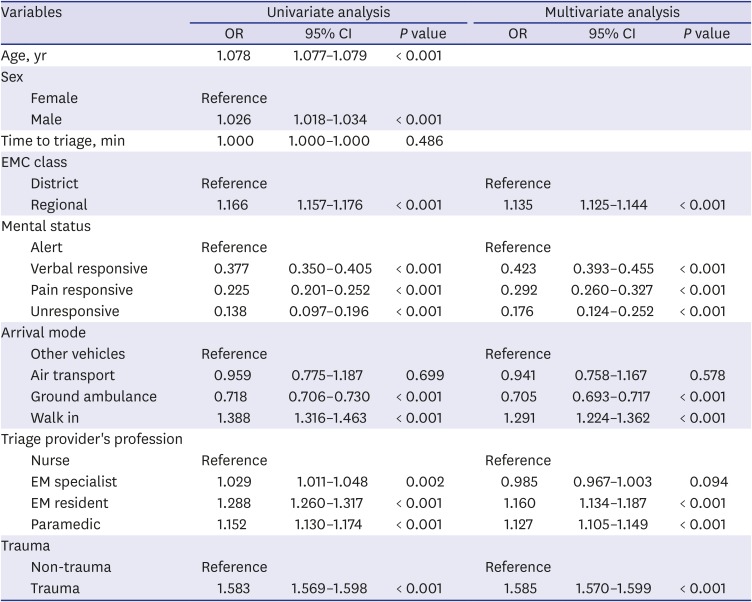

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normal distribution and median (interquartile range) for non-normal distribution. Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test was used for normality test. The Pearson's χ2 test and logistic regression analysis were used to analyze the down-triage proportion according to the characteristics such as the triage provider's profession, EMC class, and mental status. Statistically significant factors in univariate logistic regression analysis were used to derive a multivariate logistic regression model, and a final model was obtained through stepwise backward selection. In this process, variables with collinearity between factors were excluded. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria), and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

All data provided by NEDIS is de-identified, therefore the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital has approved this study for exemption from deliberation (E-1805-007-941).

Go to :

DISCUSSION

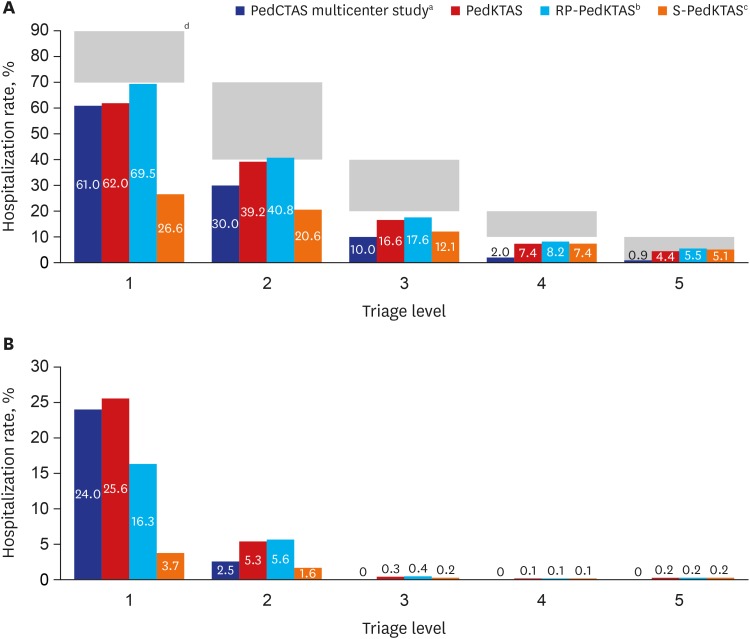

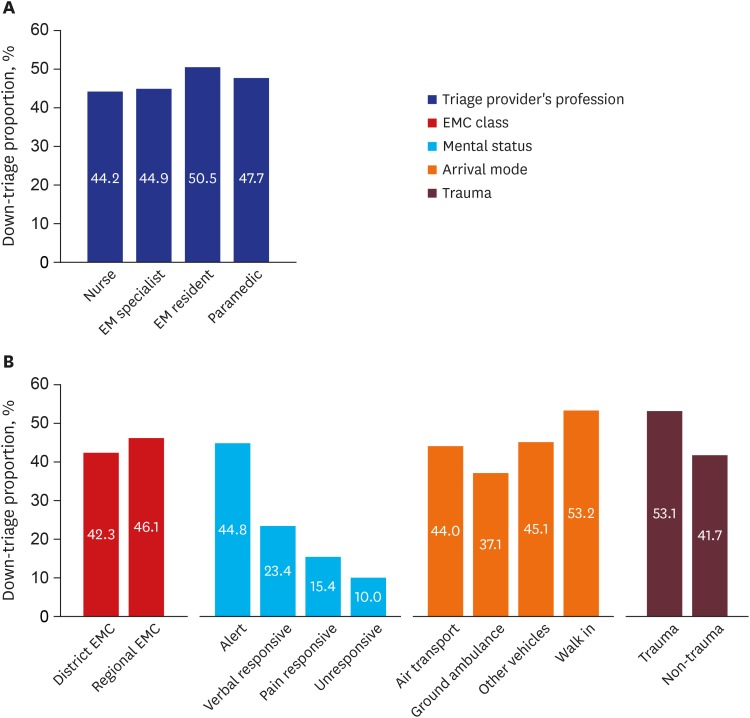

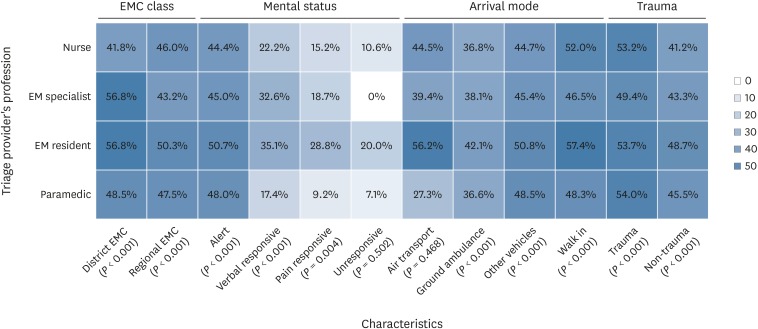

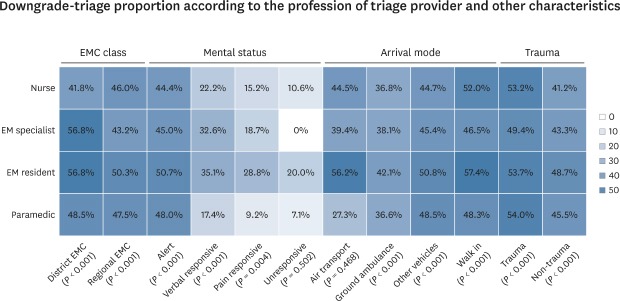

Through this study, the authors demonstrated that the discrepancy in down-triage proportion varies, depending on the triage provider's profession. According to the analysis on the subcategories, the down-triage proportion varied by 20%–30% depending on the profession of the triage provider, which is a large difference depicting a problem in the reliability of the for triage in pediatric ED.

This study showed that the discrepancy in down-triage proportion tended to decrease as the patient's mental status deteriorated. The reason for this may be because when the patient's medical condition is mild, many subjective factors influence the judgement of the triage providers; however, as the severity of the medical condition of patients aggravate, less subjective factors influence the judgement of the triage providers. It may be interpreted in this context that the difference in the professional down-triage proportion of the triage provider in the unresponsive mental status was not significant (

P = 0.502) (

Fig. 4). According to the arrival mode, the down-triage proportion of patients who walked in was the highest, followed by other vehicles, and then ground ambulance. If the severity of the patient is considered to be high in the order of ground ambulance, other vehicles, and walked in; it can be interpreted as the higher the severity of the patient's medical condition, the lower the down-triage proportion. The down-triage proportion was 44% for patients who were transported by air, which was higher than that for ground ambulance (37.1%) (

Fig. 3B). Patients arriving via air-transport do not necessarily have a more severe medical condition than patients being transported by ground ambulance, as it is mainly used to transport patients from an island or remote area to an urban medical facility. In addition, it is difficult to make precise statistical comparison because air-transported patients were only 874 (0.03%) patients of the total patients of whom were eligible for triage modification. The lower down-triage proportion in the district EMCs than the regional EMCs was also interpreted from the viewpoint that the severity of patient in the district EMCs may be higher than the regional EMC. For trauma patients, pain was a major cause of increase in heart rate and respiratory rate, therefore, these patients had a higher down-triage proportion than non-trauma patients.

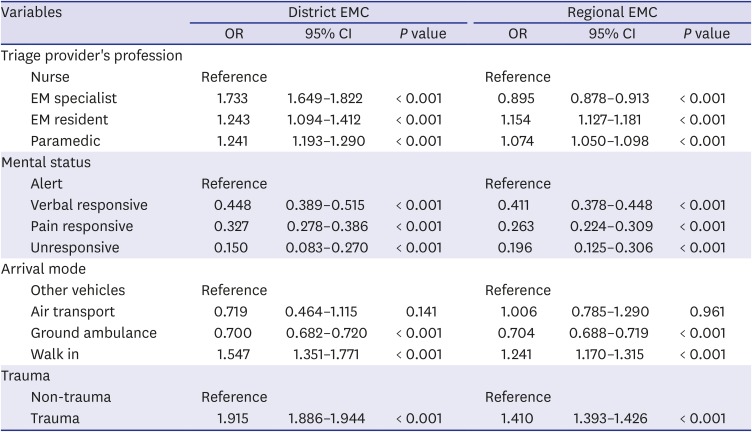

It is an interesting finding that a significant down-triage proportion discrepancy existed depending on the profession of the triage provider, which is a factor unrelated to the medical condition of the patient. The profession of the triage provider was determined by the policies and circumstances at each individual hospitals, not the medical condition of the visiting patients. In district EMCs, EM specialists and EM residents had the highest down-triage proportion (56.8%). However, in regional EMCs, EM resident's down triage proportion was 50.3%, which is still the highest down-triage proportion among all professional groups, while EM specialists had the lowest down-triage proportion of 43.2% (

Fig. 4). In addition, in multivariate logistic regression analyses, which were analyzed separately for district EMC and regional EMC, down-triage by EM specialists showed opposite results (

Table 3). Because of the retrospective nature and characteristics of the data in this study, it is difficult to explain the cause of this phenomenon. However, a plausible reason may exist in the medical insurance system of this country. In the Korean medical system, hospitals are recompensed a higher medical insurance fee from the medical insurance corporation if specialists treat patients with a higher severity, defined by KTAS level 1, 2, or 3. Some hospitals also provide additional incentives to the practicing specialist. However, it is beyond the scope of this study to elucidate further causes other than the different down-triage proportions by profession, and it cannot be deduced from the results of this study. Nevertheless, the possibility that factors unrelated to a patient's medical condition can cause discrepancies in triage levels warrants caution and revisal.

The fact that triage levels can be altered depending on non-medical situations of patients challenges the accuracy of the triage system. Considering that the accuracy of triage is of paramount importance for a timely provision of medical resources and patient safety, it cannot be overlooked. Since the reliability of the triage system is very important, many validation studies have been conducted so far,

12131415 and inter-rater reliability has been studied extensively.

1617 The reliability of CTAS and PedCTAS are high, and several previous studies have supported it.

1314151819 Although the triage system itself has proven to be reliable, if the triage provider's subjective assessment is involved in deciding whether to use the patient's abnormal vital signs for triage, the overall reliability can vary. Until now, however, there have been no reliable studies to determine whether or not the child has been measured upset vital signs. Recently, Karjala and Eriksson

17 published a prospective study to analyze the inter-rater reliability of pediatric triage instruments using vital sign parameters. In the above study, the triage levels of the same subjects were compared by ED nurse and research nurse, respectively, and the results reported good inter-rater reliability.

17 Overall, the results were somewhat contradictory to the results of this study. However, the above-mentioned study was a study that compared the results classified by two different triage providers using the same measured vital signs. It was not a study to compare whether or not to use measured vital signs as in the present study. Previous studies did not analyze the results according to whether to use abnormal vital signs in the triage process, however this study compared the difference of using abnormal vital signs according to the conditions of triage provider's profession. This was considered to be a difference from the previous studies. In addition, existing studies have been carried out at specific centers or several centers, but this study performed analysis on a national scale.

The authors are not suggesting excluding vital sign in the pediatric triage system. There is no disagreement about the reference to vital signs being obtained for healthy children. However, the authors believe that there is insufficient evidence to say that the severity increases in proportion to how far the heart rate and respiration rate deviates from the age-specific mean, or that the risk increases markedly in certain cutoffs. The authors believe that many follow-up researches need to be conduction to support the evidence. In addition, when considering the fact that a visiting child in the pediatric ED is in a state of anxiety and irritability, it is necessary to provide such a detail criterion to narrow the gap between the triage providers, rather than simply not using the vital signs measured in this situation. And another issue is that the presence of fever must be taken into consideration. It is well known that the heart rate or respiratory rate changes with body temperature. However, it is not known how the changed heart rate or respiratory rate affects the severity of the patient and how urgent treatment is required.

This study had several limitations. First, since the data used in this study were de-identified national registry data, detailed information was not available. Thus, in-depth analysis including career experience or age of the triage provider as well as regional characteristics of the study participants were not available. Second, the present study was based on triage results that were classified during actual clinical practice. Therefore, in-depth analysis such as inter-rater reliability analysis by evaluating more than one triage provider in one patient was not possible. However, this is an inevitable inherent limitation of retrospective observational studies. Finally, this study was a research carried out in the Korean medical environment, therefore, results may vary in depending on the medical environment and situation in other countries.

In conclusion, the down-triage proportion due to abnormal heart rates and respiratory rates was significantly different according to the triage provider's profession. Even if the pediatric triage system itself has good inter-rater reliability, if the evaluating factors used for triage can be changed by the triage provider's condition, the overall inter-rater reliability may also vary. Further studies are required to establish detailed criteria for applying triage to abnormal heart rate or respiratory rate in children in order to improve the accuracy of triage.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download