This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Dermatomyositis is a rare disease characterized by classic skin lesions and muscle weakness. In rare cases, life-threatening hypercalcemia may develop caused by regression of dystrophic calcifications. Here we report a 36-year-old man who presented with progressive proximal weakness, difficulty in ambulation, and weight loss. He had the V-sign, Gottron’s papules, and hard, chalky nodules on both antecubital, thigh, and hip areas. Laboratory examinations revealed hypercalcemia (3.47 mmol/L) and shortened QT interval. Workup for malignancy and tuberculosis yielded negative results. Biopsy of the antecubital areas revealed calcinosis cutis. Serum calcium levels gradually normalized with hydration and steroids. Our case illustrated that a high index of suspicion for dermatomyositis is warranted for early diagnosis and ascertaining the etiology of hypercalcemia is vital in the management of this life-threatening complication. While hypercalcemia from dermatomyositis may respond to steroids, to date, individualization of treatment remains the standard of care.

Go to :

Keywords: Dermatomyositis, Hypercalcemia, Calcinosis

INTRODUCTION

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a rare connective tissue disease with inflammation of both skin and muscle that results in a distinctive cutaneous eruption and muscle weakness. It has an incidence of approximately 9.63 per 1,000,000 presenting in adults between 40 and 60 years of age with female to male ratio is 2:11 [

1,

2]. Genetic factors and viral infections may predispose to its development, all of which can trigger an autoimmune myositis by molecular mimicry with muscle antigens. Characteristic skin manifestations include the heliotrope rash, the “V-sign”, the Holster sign, Gottron’s papules, Gottron’s sign, nail telangiectasias, and vasculitic ulcers. Other prominent features include non-erosive arthritis, skin and soft tissue calcifications and symmetric proximal muscle weakness. Notable serum tests include increased muscle enzymes, creatine phosphokinase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and lactate dehy-drogenase. Muscle biopsies often show the presence of mononuclear cells infiltrates [

2]. The anti-Jo-1 antibody is the immunological marker for DM. It has a high diagnostic specificity, but is present only in 30% of patients [

2].

DM increases the likelihood of developing malignancy by approximately 6-fold [

2-

9]. Malignancies may precede, coincide with or follow the diagnosis of DM. The greatest risk exists within the first year of diagnosis. Tumors of the breast, lung and colon are the three most common from patients in the west, whereas nasopharyngeal cancer is one of the most common cancers seen in men in Southeast Asia [

10]. Hypercalcemia is common in DM patients with associated malignancies. The main pathophysiology of hypercalcemia is an increase in bone resorption from secretion of parathyroid hormone related peptide (PTHrP) [

1-

9].

Hypercalcemia in dermatomyositis often presents with non-specific complaints such as fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, polyuria, progressive general muscle weakness, and weight loss. Severe cases presenting with generalized tonic-clonic seizures have also been reported [

10,

11]. At present, only two cases of severe hypercalcemia in juvenile dermatomyositis have been reported [

10,

11] from regression of calcinosis plaques [

12,

13]. In such cases, the serum calcium levels may be above 3.5 mmol/L, which may ultimately result in life-threatening arrhythmias [

10,

11].

Go to :

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old man was admitted for an 8-month history of progressive and generalized body pain, proximal muscle weakness, dysphagia, weight loss and gradual difficulty in ambulation leading to a bedridden state. His past medical history was unremarkable. On admission, he had generalized muscle wasting, was coherent and had stable vital signs. On examination, he had multiple, non-pruritic erythematous macules coalescing to patches over the anterior neck and upper chest, and multiple hyperpigmented papules with areas of hyperkeratosis over the metacarpophalangeal joints of both hands; and hard, white, chalky nodules on both antecubital areas and lateral areas of the hips and thighs (

Figure 1). He had difficulty moving his extremities because of contractures, generalized painful nodules, and proximal muscles weakness in both upper and lower extremities. Neurological exam did not show cranial nerve deficits or sensory deficits.

| Figure 1(A) Multiple erythematous patches on the anterior neck and upper chest (V-sign). (B) Multiple hyperpigmented papules with areas of hyperkeratosis over the metacarpop-halangeal joints, with periungual discolor-ation of both hands. (C, D) Multiple hard nodules on the bilateral antecubital areas (calcinosis cutis). Informed consent for publication of clinical data and images was obtained from the patient prior to the beginning of the study.

|

Laboratory examinations done revealed hypercalcemia at 3.47 mmol/L, ionized calcium at 1.57 mmol/L, shortened QT interval, slightly elevated serum creatinine (132 μmol/L, eGFR 59.4 mL/min/m

2), and normal serum phosphate at 1.25 mmol/L. He had anemia (hemoglobin 6.4 g/dL), and a positive direct and indirect Coomb’s test. Antinuclear antibody, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-Jo-1 antibodies, sputum acid fast bacilli stain and HIV antibodies were negative. The electromyography and nerve conduction velocity studies revealed complex repetitive discharges, which were nonspecific findings, and normal nerve conduction velocities. Chest and abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography scans were unremarkable except for multiple calcifications scattered throughout both kidneys consistent with medullary calcinosis. Skeletal survey showed the presence of multiple calcified densities in the shoulder and elbow joint areas (

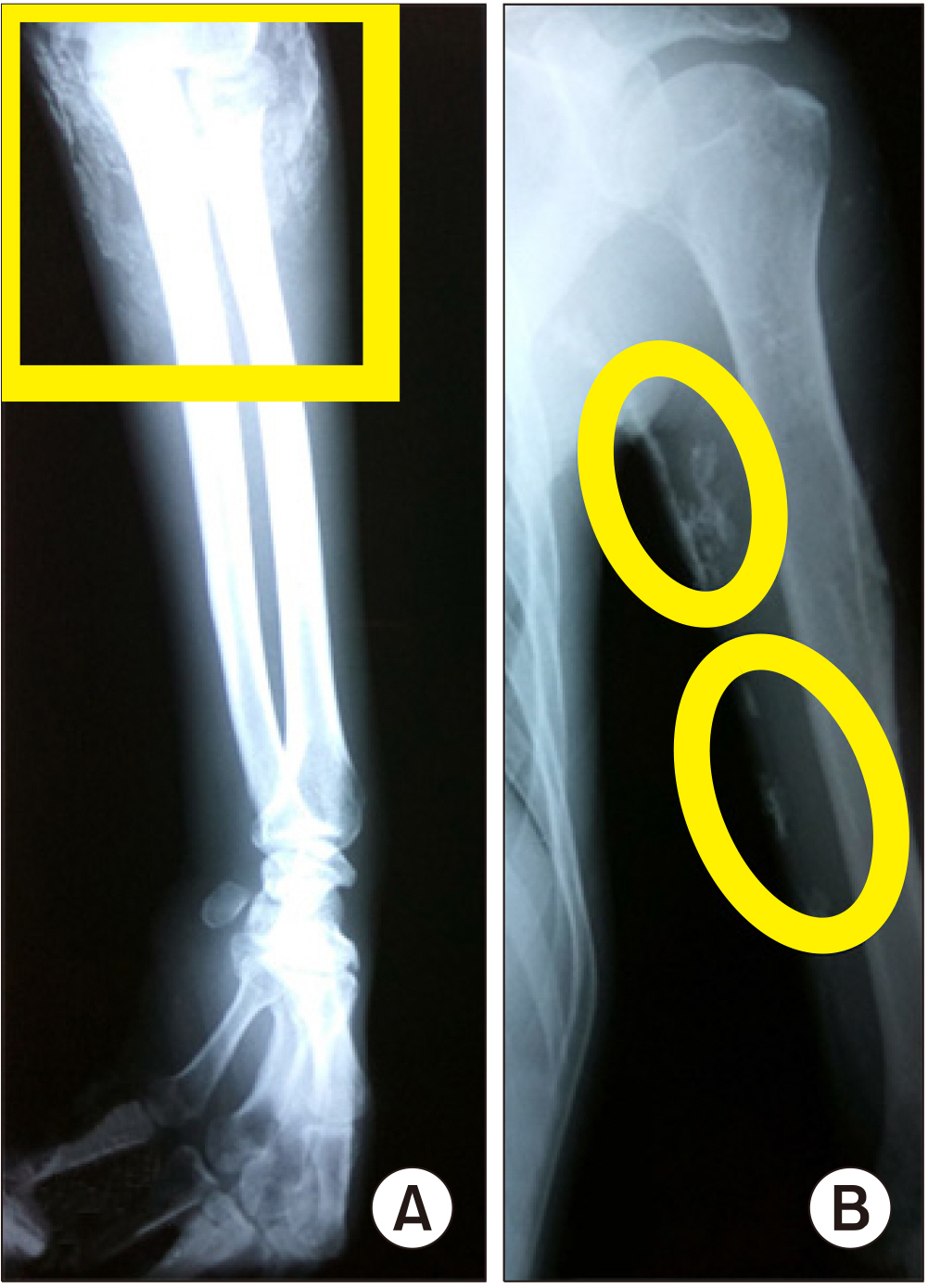

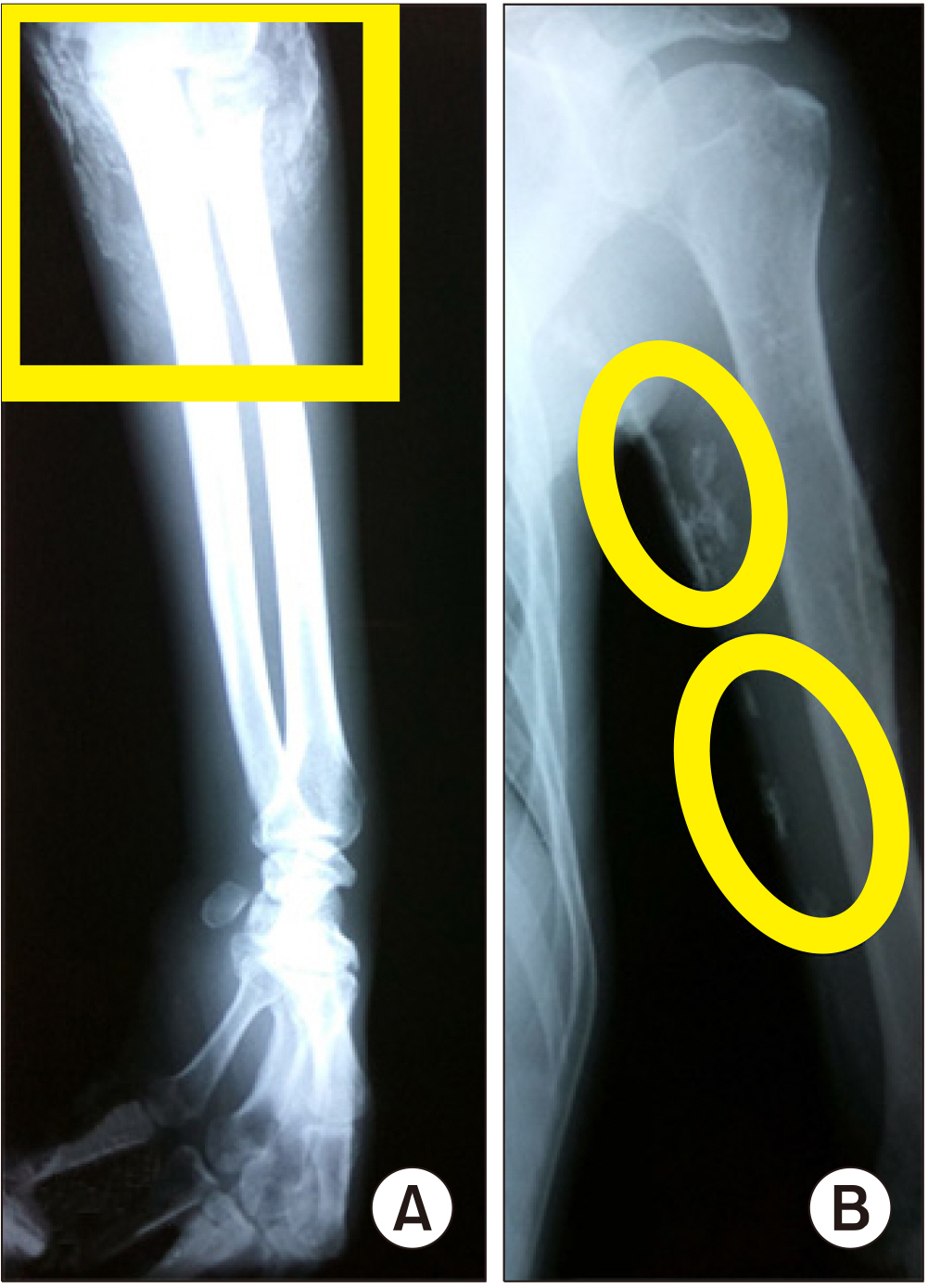

Figure 2). The intact parathyroid hormone, PTHrP, liver function tests, creatinine kinases, thyroid function tests, technetium-99m sestamibi scan, tumor markers, serum electrophoresis, chest X-ray, nasal endoscopy and two-dimensional echocardiography showed normal results. Skin biopsy of antecubital areas revealed calcinosis cutis and mixed cell infiltrates of lymphocytes, histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, both of which may be seen in DM, albeit not pathognomonic (

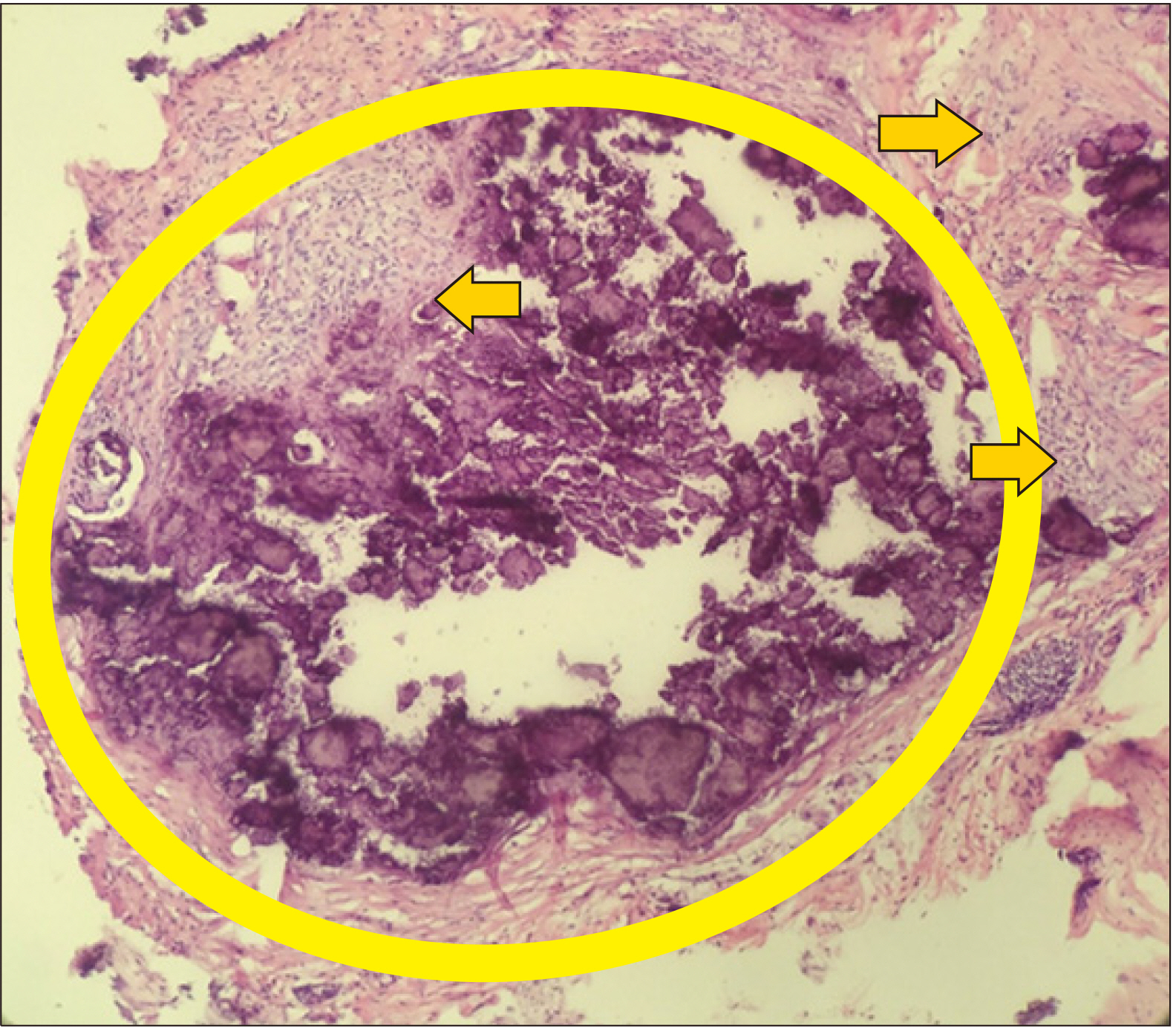

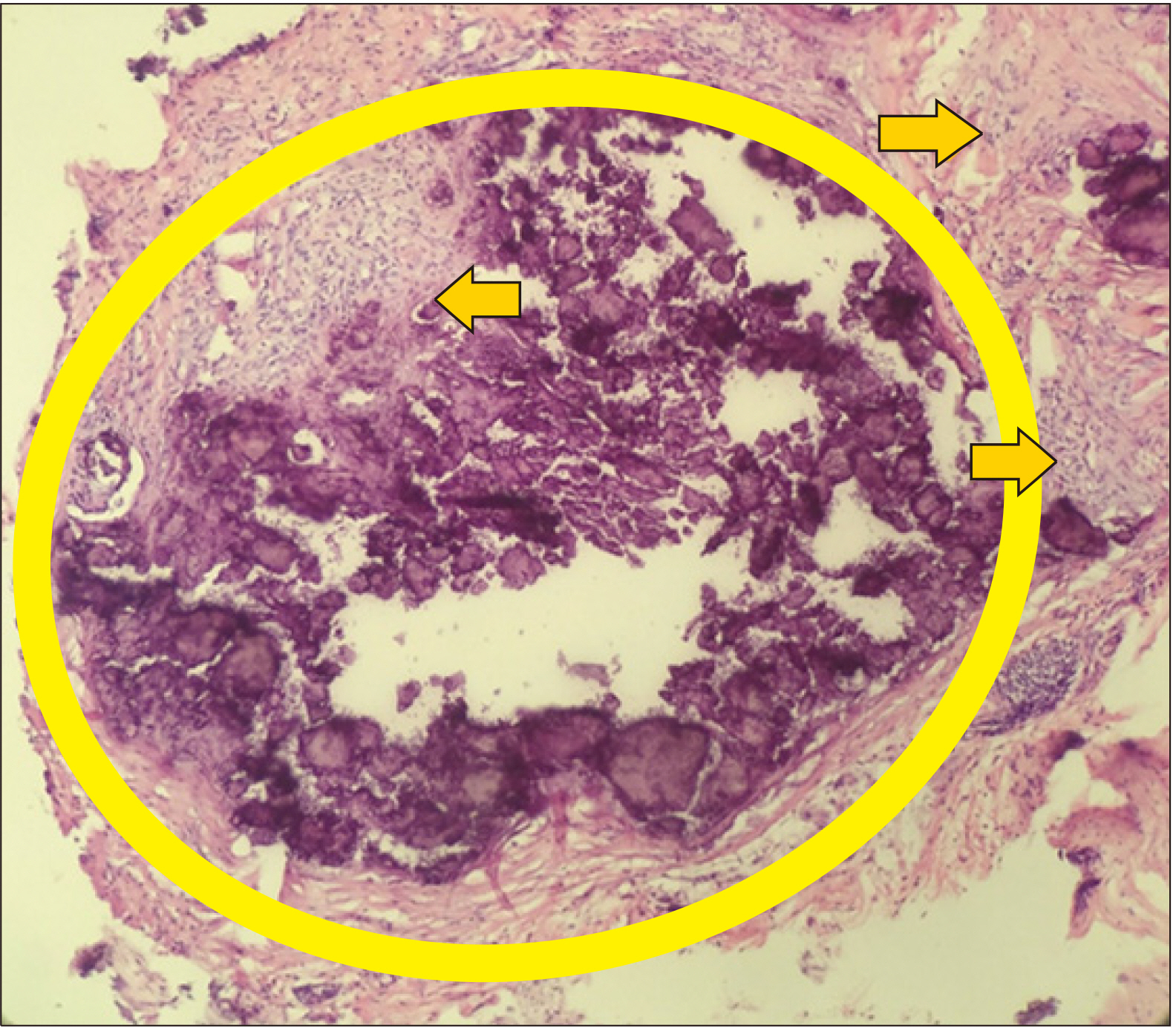

Figure 3).

| Figure 2Plain radiographs of the left elbow (A) and upper arm (B) showing multiple radioopaque areas of calcifications (ovals and rectangle).

|

| Figure 3Low-power field (×10 magnification) using H&E stain: A cylindrical skin segment biopsy of the right elbow: basophilic deposits (oval) in the dermis with surrounding cell infiltrates of lymphocytes, histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells (arrows).

|

During the course of his admission, the patient was hydrated resulting in a small drop in his serum calcium levels (3.43 mmol/L). He was initially started on high dose intravenous steroids (1 mg/kg/day) of 100 mg of hydrocortisone given every 8 hours and oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg per day. We gradually tapered down the steroid dose until we reached a 0.5 mg/kg/day equivalent. His serum calcium (2.67 mmol/L) and creatinine (104 μmol/L, eGFR 79 mL/min/m2) levels gradually normalized with hydration and steroids. He was discharged improved and was maintained on oral steroids at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day of prednisone equivalent and hydroxychloroquine, 200 mg per day. On his follow-up as out-patient two weeks post-discharge, he had an overall improved well-being, had gained weight and is able to ambulate, with less erythema of the skin lesions, decreased antecubital and thigh nodules. Repeat serum chemistry showed normal serum calcium (2.33 mmol/L), creatinine (80 μmol/L, eGFR 109 mL/min/m2), and phosphate (1.25 mmol/L) levels. We continued his steroid tapering by decreasing the dose by 0.1 mg/kg/week until we reached a dose of prednisone 5 mg/day as maintenance.

The study was registered and approved by the Research Grants and Administration Office of the University of the Philippines Manila (IRB No. RGAO-2017-1029).

Go to :

DISCUSSION

We diagnosed our patient with dermatomyositis using the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM). He satisfied the following criteria with corresponding probability scores: (1) age of onset of first related symptoms at 18∼40 years old (1.3), (2) objective symmetric, progressive weakness of both proximal upper (0.7) and lower (0.8) extremities, (3) neck flexors are relatively weaker than neck extensors (1.0), (4) proximal muscles of the legs are relatively weaker than the distal muscles (0.9), (5) Gottron’s papules (2.1), (6) Gottron’s sign (3.3), and (7) dysphagia or esophageal dysmotility (0.7). We were not able to obtain a muscle biopsy and auto-antibodies mentioned in the criteria as patient had major financial difficulties to have them done in a private institution. However, despite not having a muscle biopsy, the patient had a sum total score of 10.8, which translates to a probability of at least 90% of the patient having IIM. Furthermore, we were able to classify the patient as having DM based on the following features: (1) age at onset of first symptoms by >18 years-old, (2) the presence of Gottron’s papules and sign, and (3) the proximal, progressive muscle weaknesses on both upper and lower extremities. These criteria have a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 82% when used without a muscle biopsy [

14].

Calcinosis is a recognized feature of connective tissue diseases. Although more commonly observed in the juvenile form (approximately 40% of cases), it is rare in the adult form, affecting only 10% of patients. Its rarity in adults raises the possibility that age-dependent factors influence the risk of developing ectopic calcifications [

12,

13]. The etiopathogenesis of calcinosis is unknown. Prevailing mechanisms suggest that trauma and/or the presence of chronic inflammation can trigger calcium deposition [

10-

12]. These calcium deposits develop in a span of 3∼4 years after disease onset as a result of accumulation of hydroxyapatite crystals released from the mitochondria of damaged myocytes [

12].

Calcinosis can precede the diagnosis or even after. It is more common in the late phases of the disease, in areas under chronic stress and sites of trauma [

12,

13]. It usually presents as follows: (1) hard nodules or plaques in subcutaneous or periarticular regions; (2) tumors; (3) deposits in the intermuscular fascia, leading to mobility limitation of the affected muscles; (4) severe dystrophic calcification similar to an exoskeleton; and (5) mixed forms [

10]. The deposition of calcium in these aforementioned areas may actually cause more burden than myositis itself. Its presence can have a negative impact on the patient’s quality of life, causing weakness, functional disability, joint contractures, muscle atrophy, skin ulcers, and, consequently secondary infections [

13]. As seen in our patient, his dermal calcinosis in both upper and lower extremities had caused significant limitation in movement with severe functional decline and overall negative impact in quality of life and activities of daily living.

Delayed diagnosis and treatment, uncontrolled disease activity and disease progression are well-known risk factors for the development of cutaneous calcinosis. Early aggressive treatment remains the best method for calcinosis prevention, with no consistently effective or standard therapy currently available. Treatment remains to be challenging as no consensus has yet been achieved on efficacy, and the data available in the literature is limited to case reports/series on the use of the following medications, bisphosphonates; probenecid; warfarin; aluminum hydroxide; colchicine; diltiazem; and infliximab, all with varying degrees of success [

12,

13].

The hypercalcemia in patients with dermatomyositis with widespread calcinosis can be a result of the spontaneous regression of calcific deposits. However, the process of regression has not been well described. Only two cases of hypercalcemia in juvenile dermatomyositis have been reported back in 1984 by Wilsher et al. [

10] and Ostrov et al. [

11] in 1991 from regression of calcinosis plaques. In both cases, the hypercalcemia was responsive to steroid therapy but remained refractory to bisphosphonate treatment. Similarly, our patient presented with hypercalcemia and calcinosis cutis following a delay in diagnosis and management. His aggressive course justified the initiation of high dose intravenous steroids to control disease activity. This responsiveness to immunosuppressive therapy would suggest that the life-threatening hypercalcemia may have developed as a result of spontaneous mobilization of calcium from the deposits. His serum calcium and creatinine eventually normalized following continued treatment with oral steroids. A summary and comparison of cases is shown in

Table 1 below.

Table 1

A summary of comparative features of cases presenting with severe hypercalcemia from regression of calcinosis in dermatomyositis

|

Study |

Age (yr)/Sex |

Presentation |

Degree of calcinosis |

Treatment |

Outcome |

|

Wilsher et al., 1984 [10] |

11/Male |

Weakness, jaw pain, nausea, constipation, and grand mal convulsions with unconsciousness |

Diffuse |

Steroids (prednisone), bisphophanates and phenytoin |

Complete regression |

|

Ostrov et al., 1991 [11] |

10/Male |

Generalized body malaise, milky discharge from areas of calcinosis |

Diffuse |

Steroids (prednisone) and bisphophanates |

Complete regression |

|

Present study |

36/Male |

Generalized body pain, proximal muscle weakness, weight loss and gradual difficulty in ambulation |

Diffuse |

Steroids (hydrocortisone; prednisone) and hydroxychloroquine |

Partial regression |

Go to :

SUMMARY

In summary, our patient presented with the classic skin lesions, signs and symptoms of dermatomyositis. His laboratory examinations revealed hypercalcemia and a shortened QT interval. We managed his hypercalcemia with hydration and steroids resulting in the normalization of his serum calcium levels. A high index of suspicion for dermatomyositis is always warranted in any patient presenting with classic signs and symptoms and hypercalcemia. When the diagnosis is established, it is prudent to rule out malignancy as a cause for hypercalcemia, and at the same time take into account the regression of calcific lesions as an alternative cause. Life-threatening hypercalcemia appears to respond well to steroids. However, at present, treatment of calcinosis remains challenging, with only few available studies in literature. No therapy has yet proven to be superior apart from individualization of therapy, early recognition and prompt control of disease activity.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our team would like to extend our most sincere gratitude to Dr. Lawrence Anatalio for his excellent care of the patient, Dr. Kreza Geovien Ligaya from the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences for her help in the conduction and interpretation of the EMG-NCV, our staff from the Medical Research Laboratory, the Department of Laboratories, and the Division of Nuclear Medicine for their help in the diagnostic workup of our patient.

Go to :

Notes

Go to :

REFERENCES

1. Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, Pukkala E, Mellemkjaer L, Airio A, et al. 2001; Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 357:96–100. DOI:

10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03540-6. PMID:

11197446.

3. Mattheou‐Vakali G, Ioannides D, Lazaridou E, Kalabalikis D, Batsios P, Minas A. 1997; Dermatomyositis sine myositis in five cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 8:208–11. DOI:

10.1111/j.1468-3083.1997.tb00480.x.

4. Ni QF, Liu GQ, Pu LY, Kong LL, Kong LB. 2013; Dermatomyositis associated with gallbladder carcinoma: a case report. World J Hepatol. 5:230–3. DOI:

10.4254/wjh.v5.i4.230. PMID:

23671729. PMCID:

PMC4248508.

5. Ghazi E, Sontheimer RD, Werth VP. 2013; The importance of including amyopathic dermatomyositis in the idiopathic inflammatory myositis spectrum. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 31:128–34. PMID:

23190767. PMCID:

PMC3883437.

6. Udkoff J, Cohen PR. 2016; Amyopathic dermatomyositis: a concise review of clinical manifestations and associated malignancies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 17:509. DOI:

10.1007/s40257-016-0199-z. PMID:

27256496.

7. Tiniakou E, Mammen AL. 2017; Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and malignancy: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 52:20–33. DOI:

10.1007/s12016-015-8511-x. PMID:

26429706.

8. Sigurgeirsson B, Lindelöf B, Edhag O, Allander E. 1992; Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 326:363–7. DOI:

10.1056/NEJM199202063260602. PMID:

1729618.

9. Callen JP. 2002; When and how should the patient with dermatomyositis or amyopathic dermatomyositis be assessed for possible cancer? Arch Dermatol. 138:969–71. DOI:

10.1001/archderm.138.7.969. PMID:

12071827.

10. Wilsher ML, Holdaway IM, North JD. 1984; Hypercalcaemia during resolution of calcinosis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 288:1345. DOI:

10.1136/bmj.288.6427.1345. PMID:

6424852. PMCID:

PMC1440957.

11. Ostrov BE, Goldsmith DP, Eichenfield AH, Athreya BH. 1991; Hypercalcemia during the resolution of calcinosis universalis in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 18:1730–4. PMID:

1787495.

13. Terroso G, Bernardes M, Aleixo A, Madureira P, Vieira R, Bernardo A, et al. 2013; Therapy of calcinosis universalis complicating adult dermatomyositis. Acta Reumatol Port. 38:44–8. PMID:

24131911.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download