DISCUSSION

In many countries, including Turkey, there are health policies and health implementation programs regarding EBF in the first 6 months of a child's life and the provision of solid food along with breast milk starting at the sixth month of life. However, studies have shown that recommendations made by various authorities, such as WHO, may not be fully implemented. Recent data has shown that the EBF rate at 6 months of age is only 25.0% in the European region and 43% in the South-East Asia region. Despite the high breastfeeding initiation rates at birth in many countries, EBF rates have been reported to gradually decline over time, resulting in rather low EBF rates at 6 months of age, particularly in the European region [

10]. Data presented in the latest available Turkey Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS) show that the rate of EBF in Turkey was 41.0% [

11]. The TDHS showed that the rate of exclusively breastfed children decreases rapidly with age to 14.0% in 4–5-month-old children. Moreover, the breastfeeding rate of children in the first hour after birth was 71.0%, while the percentage starting complementary foods at 6

th months was 85.0%, and the rate of breastfeeding during the first year was 66.0% [

11]. These results reveal that the targeted rates have not yet been reached in Turkey.

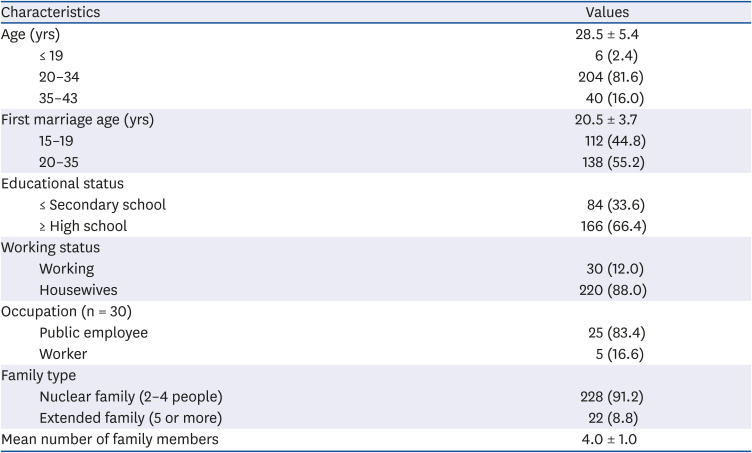

In the present study, it was observed that 97.2% of the mothers breastfed their children. This rate is similar to the rate for all of Turkey (98%) [

11]. Carletti

et al. [

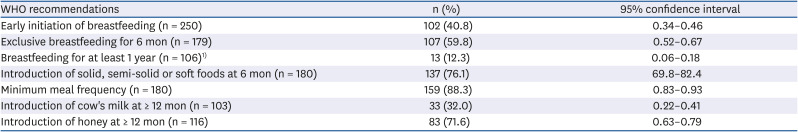

12] reported that 98.0% of women breastfed their children after birth. It is encouraging that the first food provided by mothers to their babies is breast milk because the content of breast milk is important in initiating a metabolic adaptation of the baby after birth, and it has features indicating it is the most suitable food. However, the rate of initiating breastfeeding within one hour after birth of the baby was 40.8% (

Table 4). This low rate may be because some mothers do not have sufficient knowledge about the importance of early breastfeeding or that health personnel did not adequately inform the mother of that importance.

The WHO has reported that the EBF rate is below the globally targeted rate (at least 50.0%) by 2025 [

13]. Globally, EBF status is about 40.0% [

14],

The WHO/UNICEF have reported that the EBF rate is below the globally targeted rate (at least 50.0%) by 2025 [

13]. Globally, EBF status is about 40.0% [

14], and the rate of EBF in Turkey is 41.0% [

11]. In the 2010 TNHS, the EBF duration was reported to average 5.3 months [

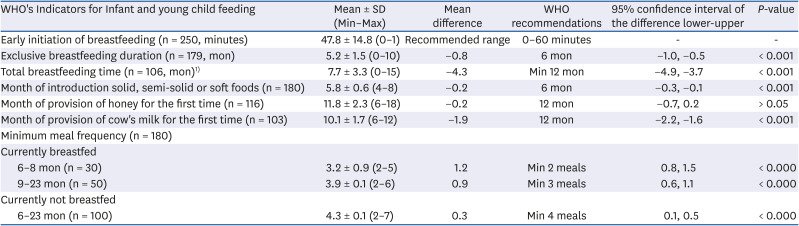

8]. Similarly, in the present study the mean duration of EBF was 5.2 ± 1.5 months (

Table 3), and 59.8% of the mothers in this study complied with the WHO recommendation of EBF for 6 months (

Table 4); results that agree with the results reported by Carletti

et al. [

12]. However, the average duration of mothers' breastfeeding in the present study was 7.7 ± 3.3 months. This outcome is significantly lower than the recommended duration (

P < 0.001,

Table 3). Moreover, the percentage of mothers who breastfed their babies for one year or more was only 12.3% (

Table 4). Interestingly, this is notably higher in developing countries. For example, Kimani-Murage

et al. [

15] reported this rate was about 85.0% in Nairobi-Kenya, while Lauer

et al. [

16] reported it as 91.8% in Africa, 87.5% in Asia (including Japan), and 59.9% in Latin America and the Caribbean. The differences between our study and these studies may be related to differences between countries' policies on breastfeeding. On the other hand, such differences are often considered to be caused by cultural differences among countries and by socio-economic factors. Changes in socio-economic factors are considered to affect breastfeeding. For example, in the poorest countries, late initiation of breastfeeding and low EBF rates are common, with fewer than 40% of children under 6 months being breastfed only. A short overall breastfeeding duration poses additional challenges, especially in middle- and high-income countries, where less than one in five children are breastfed during the first 12 months [

17].

Nutritious food is vital in children 0 to 24 months of age because it is a determinant of both childhood and adulthood health [

18]. Infant deaths can be decreased by 1/3 by providing complementary food in a timely fashion [

19]. However, a previous study indicated that starting complementary feeding before the recommended time increases the frequency of food allergies, allergic rhinitis, and asthma [

20]. Moreover, a decrease in the duration of breastfeeding is associated with childhood obesity, which is an increasing global health problem. For example, Gubbels

et al. [

21] reported that infants who were breastfed until the end of the first 12 months of life had lower body weights and BMI z-scores. Monasta

et al. [

22] reported that the absence of or a short breastfeeding period was one of five factors associated with overweight status and obesity in children and adults.

Starting the provision of complementary food before the sixth month of life is a common mistake made by mothers. Many factors can affect a mothers' decision to provide complementary foods. For example, mothers may believe that when they give their babies various foods (especially liquids) before the sixth month, it will be good for colic, gas, gastroesophageal reflux, and thirstiness in babies, and if they continue to breastfeed simultaneously, mothers may assume they are exclusively breastfeeding, even if in reality they are not [

2324]. In addition, the problematic practice of providing complementary foods too early can result in decreased breast milk production.

In the present study (

Table 3), mothers started giving complementary food before the sixth month (5.8 ± 0.6 months), which is not compatible with the WHO recommendation. However, the difference was slight (mean difference: 0.2 month). In addition, 76.1% of mothers started providing complementary foods at the 6

th month (

Table 4). In a previous study, only 33.2% of the mothers started complementary feeding in compliance with WHO recommendations [

25]. In another study, it was reported that 60.5% of the mothers started complementary feeding at the recommended time [

19]. Mothers who started complementary feeding early stated the reason for this as insufficient breast milk [

1926], lack of knowledge, and the difficulty in accessing a health center [

19]. In this study, the rate of mothers who started complementary feeding at the recommended time (6

th month) was high, which is beneficial because complementary feeding is crucial in preventing health problems. In another study, about 2/3 of the mothers (77.0%) started complementary food later than recommended [

27]. Such differences may be caused by cultural differences in the countries in which these studies were conducted. Regardless, some results may be considered evidence that mothers fail to understand the importance of EBF, or they may present such behaviors because of difficulties in achieving EBF.

In this study, the time at which cow's milk was provided as a complementary food was 1.9 months earlier than the recommended time (

P < 0.001,

Table 3). Only 32.0% of the mothers fed the infants with cow's milk for the first time at the recommended 12

th months or later. In their study Carletti

et al. [

28] reported that 63.0% of mothers gave cow's milk to their babies for the first time at 12 months or later. The American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend providing cow's milk before 12 months of age [

29], and supplementary feeding with cow's milk before the recommended age is an independent risk factor for iron deficiency anemia [

30], which may deteriorate cognitive and emotional development of infants [

31]. Cow's milk is one of the first food types typically used in infant feeding [

32] and can result in a food allergy. The estimated prevalence of cow's milk allergy is reported to be between 2% and 7% [

33]. On the other hand, excessive protein consumption in the first 12 months can increase the incidence of chronic diseases, such as obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and kidney diseases [

34]. Therefore, starting cow's milk in the recommended month or later should contribute significantly to the health of children throughout their lives.

Honey, another food often provided as part of a child's diet, can act as a reservoir for

Clostridium botulinum spores, which are associated with the development of infant botulism. Thus, it is inappropriate to feed honey to infants before they reach an age of 12 months [

35]. In the present study, the average month when honey was given to babies for the first time (11.8 ± 2.3 months) was in accordance with the recommended start time. Furthermore, 71.6% of mothers gave honey to their babies for the first time at or after the 12

th month, in accordance with the WHO recommendation. Carletti

et al. [

28] reported that 80.0% of mothers gave honey to their babies for the first time at the 12

th month or later.

In this study, mothers provided the minimum number of meals to their infants in accordance with the recommendations based on age (

Table 3). Most (88.3%) mothers fed their babies at frequencies that complied with the WHO recommendations (

Table 4). Aggarwal

et al. [

27] reported that infants were provided complementary food two (52.4%) or three times (31.5%) a day, but the results were not classified by months. These results show that mothers are sensitive to their child's feeding times. Some of that sensitivity is due to cultural practices.

Maternal age is associated with infant breastfeeding practices [

36]. In some studies, it was determined that older mothers are less likely to breastfeed [

3637]. In contrast, other studies revealed that young mothers have an increased risk of early cessation of EBF compared to older mothers [

3839]. In this study, it was observed that younger mothers had higher rates of compliance with the WHO recommendations than those of older mothers. Although there was no statistical significance to that difference, it is notable that the younger mothers had a higher rate of compliance, which may be explained by the relationship between the educational level and age of the mothers. That relationship showed that most young mothers (71.2%) had a higher level of education than that of older mothers (67.3%) (

P < 0.05). In addition, the results indicate that the educational status of mothers is associated with compliance to the WHO recommendations.

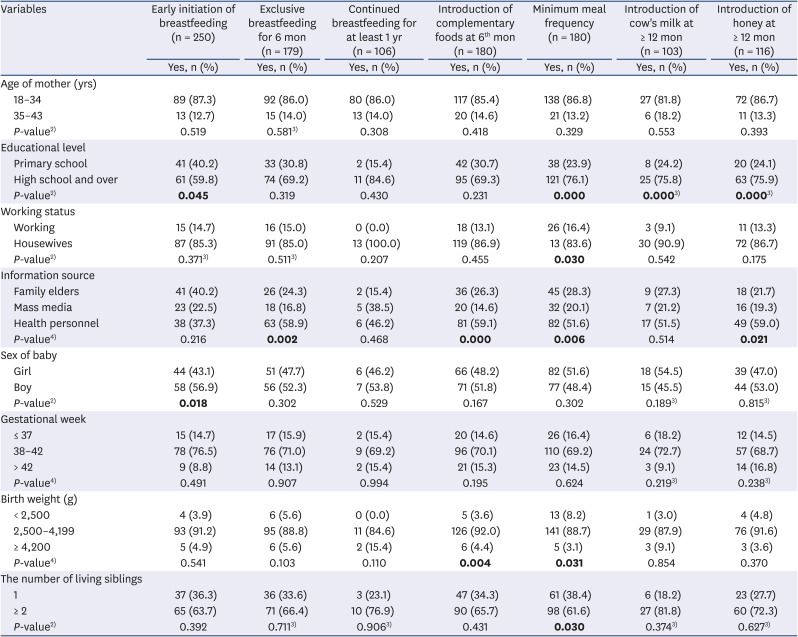

In this study, compared to mothers with a lower education level, mothers with a higher level of education started breastfeeding significantly earlier (59.8%,

P < 0.05), and more than half of them (69.2%) continued EBF (though not statistically significant). As well, 84.6% of them continued breastfeeding until the end of 12 months of age. In addition, the number of women with a higher level of education who started providing complementary food at the 6

th month was greater than that of primary school graduate mothers. Moreover, mothers with a higher education level complied to a greater extent with the WHO recommendations on the number of meals (77.1%) and the times to start giving cow milk (75.8%) and honey (75.9%) (

P < 0.05,

Table 5). Based on the results, it can be concluded that the mothers with a high school or better level of education exhibit better compliance with recommendations on baby nutrition. Various studies have shown that education level is positively correlated with compliance with EBF and complementary feeding practice recommendations [

4041].

It has been reported that a mother's working status can affect her breastfeeding behavior; in particular, full-time work has a strong negative effect on the duration of breastfeeding [

42]. That study confirms Kumar

et al.'s [

42] thesis that the rates of working mothers complying with the WHO recommendations are quite low. Mothers should be encouraged to work during the postpartum period, but measures to continue breastfeeding should also be encouraged.

Some studies have shown that mothers will obtain information on child nutrition from family elders, health staff, and mass media [

4344]. In this study, nearly half of the mothers stated that they obtained information on child nutrition from health personnel (43.6%), as well as from family elders and mass media. This result parallels those in the 2010 TNHS [

8]. In addition, our study revealed that the compliance rates of mothers were highest among those who used health personnel as an information source (

P < 0.05,

Table 5).

In the study, it was determined that most mothers with a high school and above educational level (73.4%) used health personnel as the source of nutrition information, whereas mothers with a primary school education (46.0%) asked their parents for such information (P < 0.05). In addition to the result showing that mothers' compliance with WHO recommendations increased as the mothers' level of education increased, it was also observed that education level affected the choice of information source and therefore affected the compliance rate.

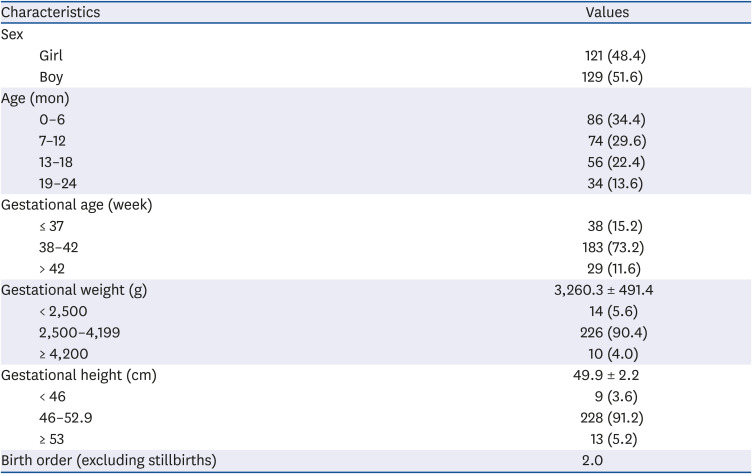

In a previous study, complementary foods were started on time 2.5 times more in boys than in girls [

19]. In the present study, the rate of providing complementary food in boys was higher than that in girls, but the difference was not statistically significant (51.8% and 48.2%, respectively) (

Table 5), which may be due to a lack of sex-based discrimination among the mothers in this study. Most babies with a birth weight between 2,500 and 4,199 g were first given complementary food at the sixth month (92.0%). In addition, adherence to the minimum frequency of meals was significantly higher (88.7%) in 2,500–4,199 g babies, than in low birth weight (< 2,500 g) babies (

P < 0.001).

Some studies have shown that breastfeeding behaviors differ between mothers with one child and mothers with more than one child. As well, some studies have shown that mothers who had two and more children were better at meeting recommendations on breastfeeding practices [

4546]. However, other studies detected no significant relationship between the number of children and breastfeeding practices [

4748]. In this study, compared to mothers with one child, mothers with more than one child exhibited higher compliance with WHO recommendations. This result is thought to be related to the mother's previous childcare associated with their first child.

In this study, almost all mothers breastfed their babies for some period after birth. However, the observed rates of initiation of breastfeeding, EBF, and duration of breastfeeding were less than the recommended levels. About two-thirds of the mothers in this study started complementary food on time. In addition, the recommended frequency of meals was provided by the majority of the mothers. However, most started cow's milk earlier than recommended. In this regard, mothers should be supported by providing more information about the WHO recommended child feeding practices. In order to provide such support, more intensive efforts are needed to develop policies that encourage the implementation of the WHO recommendations. Regulations could be made to facilitate the implementation of these policies in workplaces, especially among working women. We think that recommendations on breastfeeding and early childhood nutrition will be realized more fully by emphasizing the positive effects of breastfeeding until the age of two and the benefits of a timely start of complementary food provision on health in the long run.

This research is important because it reveals the compliance of mothers living in a less developed central Anatolian city in Turkey with the WHO child feeding recommendations, as well it has detected relationships between the feeding practices of mothers and various socio-demographic factors.

However, only two family health centers and only two months were available to carry out the study, thus restricting the size of the study. Further research with larger sample sizes will be needed to clarify the association between compliance with WHO recommendations and various socio-cultural and socio-economic variables. Such expanded studies will help identify problems in implementing the WHO recommendations. In this context, we view the results of this study as preliminary data that will form a basis for future studies into factors affecting the nutrition of children. Furthermore, the results contribute to the literature on this globally important subject.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download