This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly contagious disease caused by the novel virus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2. The first case developed in December, 2019 in Wuhan, China; several months later, COVID-19 has become pandemic, and there is no end in sight. This disaster is also causing serious health problems in the area of cardiovascular intervention. In response, the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology formed a COVID-19 task force to develop practice guidelines. This special article introduces clinical practice guidelines to prevent secondary transmission of COVID-19 within facilities; the guidelines were developed to protect patients and healthcare workers from this highly contagious virus. We hope these guidelines help healthcare workers and cardiovascular disease patients around the world cope with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Go to :

Keywords: COVID-19, Cardiovascular diseases, Coronary angiography, Percutaneous coronary intervention, Practice guideline

INTRODUCTION

In the year 2020, a new highly contagious and fatal infectious disease, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is sweeping the globe. It is causing various health problems besides direct infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. There are many critical diseases, some of which require emergency management, in the spectrum of cardiovascular disease. In particular, interventional cardiologists treat coronary artery disease, which requires a lot of human, facility, and device resources, and thus are at greater risk of exposure to various contagious materials than some other medical practitioners. With the accumulation of unfortunate experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, interventional cardiologists now recognize that not only confirmed infection but also suspected infection drastically restricts available medical resources.

1) Furthermore, in the case of emergency procedures, all participants must wear personal protective equipment (PPE), which extends the time before treatment commences and increases the difficulty of the procedures due to the physical limitations brought on by the protective equipment. After a procedure, it is essential that all facilities and equipment be disinfected and that the facilities be locked down for a certain period of time. This has had unfortunate consequences, and even patients who could have been saved have become critically ill or died without proper treatment. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 disaster is ongoing and there is no end in sight.

In response, the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology decided to come up with medical guidelines to minimize confusion and concerns among medical staff in consideration of the available medical resources that can be mobilized to manage cardiovascular diseases in Korea. This document was created in consideration of the status of various hospitals in Korea. The situation and circumstances of each hospital may vary, so it is recommended that every reader adapt the guidelines to best suit the individual institution.

Go to :

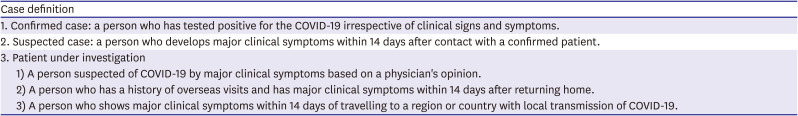

WHO MUST BE TESTED FOR COVID-19 INFECTION

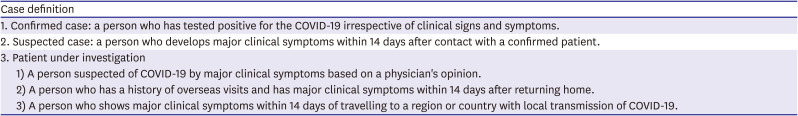

In the COVID-19 pandemic, all individuals visiting most Korean hospitals are potential sources of COVID-19. Among patients, those who need attention can be classified as a confirmed case, a suspected case, or a patient under investigation (PUI) as follows, according to the case definition of the Korea Centers for Disease Control (

Table 1).

2)

Table 1

Case definition of COVID-19* infection of the Korea Centers for Disease Control (updateable)

|

Case definition |

|

1. Confirmed case: a person who has tested positive for the COVID-19 irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms. |

|

2. Suspected case: a person who develops major clinical symptoms within 14 days after contact with a confirmed patient. |

|

3. Patient under investigation |

|

1) A person suspected of COVID-19 by major clinical symptoms based on a physician's opinion. |

|

2) A person who has a history of overseas visits and has major clinical symptoms within 14 days after returning home. |

|

3) A person who shows major clinical symptoms within 14 days of travelling to a region or country with local transmission of COVID-19. |

Confirmed patients must be isolated and adequate protection is necessary for medical staff and caregivers. Meanwhile, most Korean hospitals conduct body temperature measurements and take patient histories at the entrance of hospital buildings, so individuals highly suspicious of COVID-19 cannot enter the hospital building, and are instead guided to a regional outside screening office set up specifically for COVID-19 testing. These procedures minimize the chance of COVID-19 spread by elective patients, but in emergency cases, these avenues of control may be incapacitated. For example, in the case of emergency diseases such as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), efforts to reduce the risks to patients through rapid treatment can lead to an increase in the risk of infection of medical staff. So, an optimal response scenario should be created, understood, and trained for in advance to ensure safe and rapid treatment in case of emergency. The COVID-19 screening test using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction currently takes 4–6 hours to return results in Korea. It is recommended that providers choose diagnostic and therapeutic modalities that require minimal transportation of the patient. If a suspected patient's condition allows the individual to wait for the test results, further management that would necessitate more transportation and contact should be postponed to minimize the risk of contagion and conserve medical resources.

Go to :

TRANSPORTATION OF CONFIRMED OR SUSPECTED COVID-19 PATIENTS

When a confirmed patient, a suspected patient, or a PUI visits the emergency department (ED) with problems requiring emergency care, he or she must be guided to specific sections in the ED, and the inside of this space should be considered contaminated.

For essential management to be possible within this space, indispensable diagnostic equipment such as electrocardiogram, X-ray, and echocardiography machines should be ready for immediate use. Also, a resource management plan must be established to ensure that such equipment can be used exclusively in that space or to cope with a break period for disinfection after contamination.

When emergency procedures for potentially contagious patients are discussed, transfer from the emergency room to the catheterization laboratory (Cath Lab) is generally highlighted as a major problem. This transfer requires additional personnel and equipment. A network of contacts must be established, how to mobilize the necessary personnel for transfer should be discussed, and the necessary transport equipment must be available.

During transportation between the ED, Cath Lab, and intensive care unit (ICU) or ward, the patient should be kept isolated in a negative pressure carrier. Security personnel wearing a N95 respirator and gloves should secure the patient's transfer path in advance. The transport team members should wear level D PPE and stay close to the patient during transport. After completion of the transfer, sanitary workers must disinfect the entrances, corridors, elevators, stretcher, and negative pressure carrier used for transport while wearing N95 respirators, gowns, and gloves using 1:50 chlorine bleach or CaviWipes™.

Go to :

AIR CONDITIONING OF THE CATH LAB

In most hospitals in Korea, the air conditioning system in the Cath Lab is designed as a positive pressure system to prevent infection from the outside. Unfortunately, if a procedure is performed with positive pressure maintained, contagious floating particles will spread outside the Cath Lab. So, the positive pressure air conditioning system should be shut off before the procedure. A negative pressure air conditioning system is recommended when COVID-19-positive patients are treated, if available.

Go to :

APPLICATION OF PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT FOR CATH LAB WORK

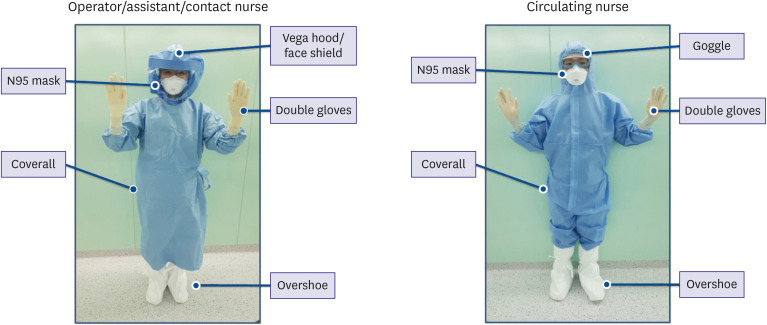

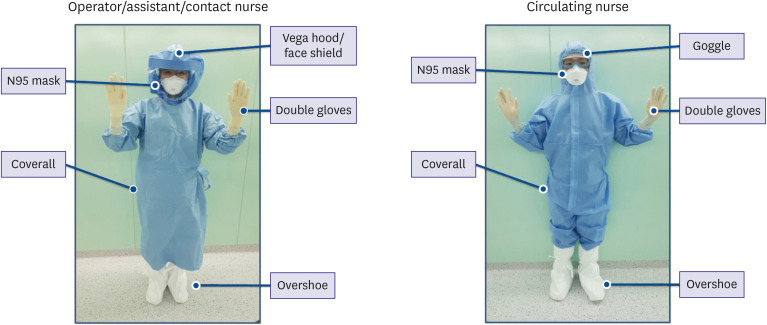

The application of protective gear may be unfamiliar to Cath Lab workers because most situations do not call for it. When donning and doffing of protective gear is required in the Cath Lab, any mistakes during the procedure can lead to failure to protect others from the source of infection. Therefore, it is advisable to define the appropriate use of each type of protective gear and post guidelines in a highly visible location. When airway intubation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is necessary, a large amount of contagious aerosol is generated, so in these situations hospitals should limit the number of participating medical staff and consider providing the medical staff with powered air purifying respirators.

When performing Cath Lab work in hazardous situations, level D PPE should be worn starting directly after the scrub process, when basic surgical suits would be donned in normal situations. On top of this, surgical gowns and gloves should be worn during the procedure. In normal daily practice, a surgical suit, lead apron, surgical gown, and one layer of gloves are put on the body, while in COVID-19 situations, a surgical suit, level D PPE, lead apron, surgical gown, and 3 layers of gloves are put on the body, resulting in substantial inconvenience during the procedure. Moreover, the interventionists must tolerate difficulty breathing and blurred vision caused by N95 respirators and goggles or face shield (

Figure 1). Some physicians use an alternative method that omits the outer layer of gloves when wearing level D PPE to reduce the number of glove layers to 2.

| Figure 1 Composition of personal protective equipment by role.

|

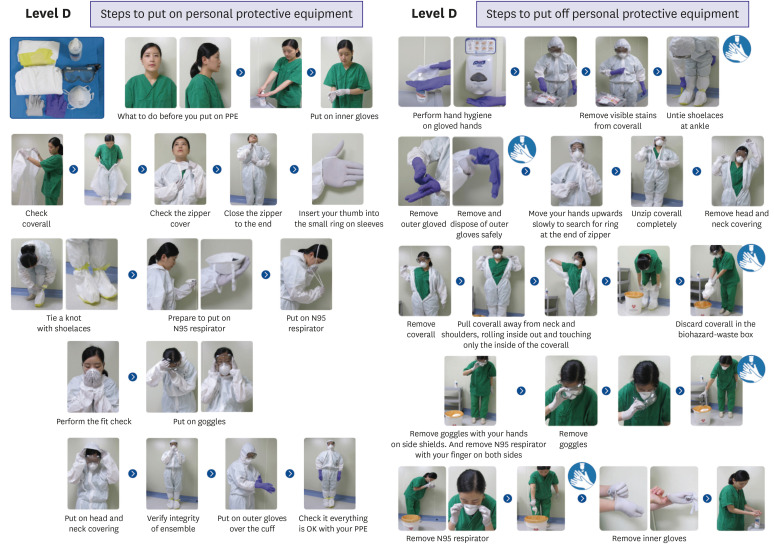

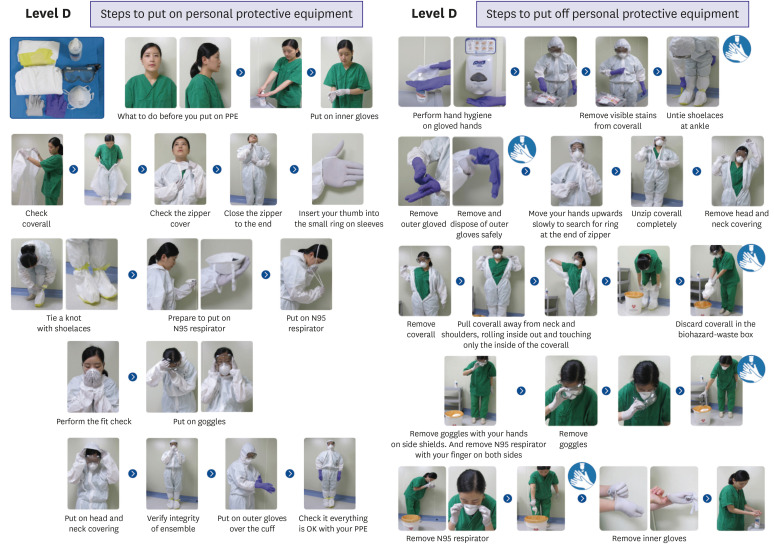

The donning and doffing of protective gear should be performed in the correct order in a place free from contamination (

Figure 2).

3)

| Figure 2 The donning and doffing of level D personal protective equipment (from Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention modified).

|

Go to :

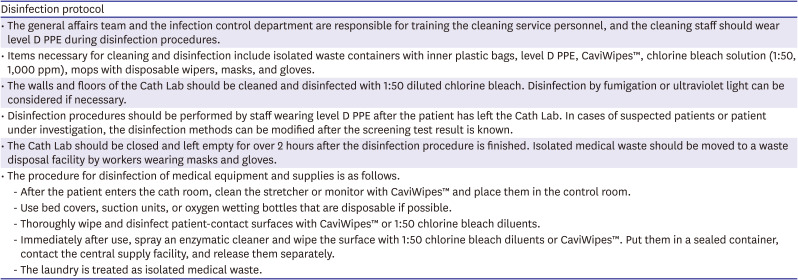

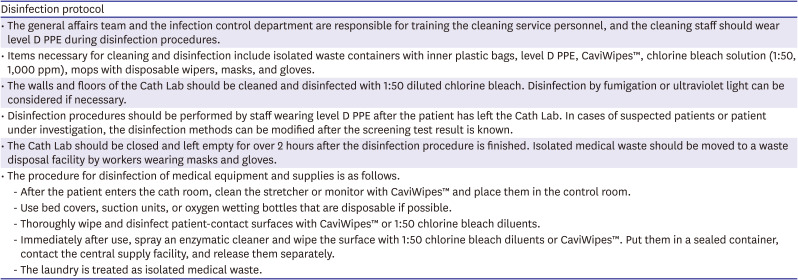

LOCKDOWN, DISINFECTION AND REOPENING OF THE CATH LAB

Advance planning for disinfection of the Cath Lab after a procedure on a confirmed or suspected patient should be in place in coordination with all departments involved. The agents, method of disinfection, and ventilation method to be used for environmental disinfection should be determined in advance, and the duration of lockdown until reopening of the Cath Lab should be specified. Thorough cleaning may require extra time; therefore, if feasible, such cases should be performed as the final procedure of the day (

Table 2).

Table 2

An example disinfection protocol in a Korean hospital

|

Disinfection protocol |

|

• The general affairs team and the infection control department are responsible for training the cleaning service personnel, and the cleaning staff should wear level D PPE during disinfection procedures. |

|

• Items necessary for cleaning and disinfection include isolated waste containers with inner plastic bags, level D PPE, CaviWipes™, chlorine bleach solution (1:50, 1,000 ppm), mops with disposable wipers, masks, and gloves. |

|

• The walls and floors of the Cath Lab should be cleaned and disinfected with 1:50 diluted chlorine bleach. Disinfection by fumigation or ultraviolet light can be considered if necessary. |

|

• Disinfection procedures should be performed by staff wearing level D PPE after the patient has left the Cath Lab. In cases of suspected patients or patient under investigation, the disinfection methods can be modified after the screening test result is known. |

|

• The Cath Lab should be closed and left empty for over 2 hours after the disinfection procedure is finished. Isolated medical waste should be moved to a waste disposal facility by workers wearing masks and gloves. |

|

• The procedure for disinfection of medical equipment and supplies is as follows. |

|

- After the patient enters the cath room, clean the stretcher or monitor with CaviWipes™ and place them in the control room. |

|

- Use bed covers, suction units, or oxygen wetting bottles that are disposable if possible. |

|

- Thoroughly wipe and disinfect patient-contact surfaces with CaviWipes™ or 1:50 chlorine bleach diluents. |

|

- Immediately after use, spray an enzymatic cleaner and wipe the surface with 1:50 chlorine bleach diluents or CaviWipes™. Put them in a sealed container, contact the central supply facility, and release them separately. |

|

- The laundry is treated as isolated medical waste. |

Go to :

PATIENTS WITH CARDIOGENIC SHOCK AND/OR CARDIAC ARREST REQUIRING INTUBATION, SUCTIONING, OR CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION

Patients with resuscitated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and/or cardiogenic shock continue to be the highest risk subgroup of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). These patients will also present the highest risk for droplet-based spread of COVID-19 because intubation, suction, and active CPR likely result in aerosolization of respiratory secretions, increasing the likelihood that personnel are exposed to the virus. Otherwise, patients who are already intubated pose less of a transmission risk to staff members given that their ventilation is managed through a closed circuit. Therefore, patients with COVID-19 or suspected COVID-19 requiring intubation should be intubated prior to arrival at the Cath Lab. All Cath Lab personnel should wear proper personal protection including PPE. Consideration of revascularization and potential mechanical circulatory support for patients in cardiogenic shock should proceed.

4)5) When feasible, bedside placement of mechanical circulatory support or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may decrease the risk of exposure. The approach taken is dependent on the local availability of resources and the COVID-19 disease burden in the community. Close coordination with critical care, infectious disease, and anesthesia teams for airway management will be critical to avoid spread of infection.

Go to :

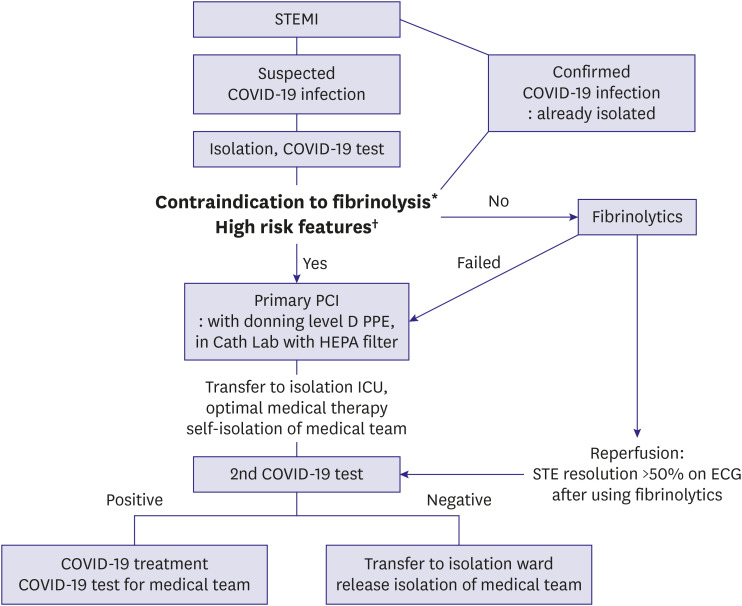

ST-SEGMENT ELEVATION MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

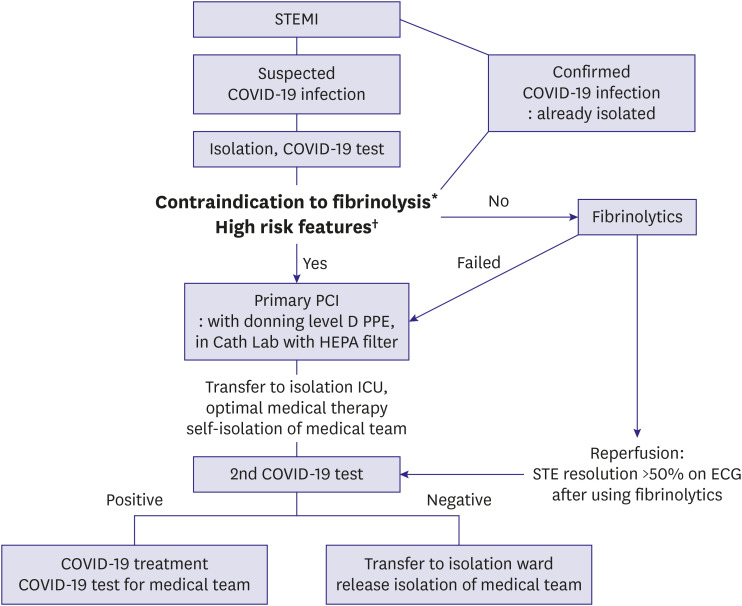

It is necessary to consider treatment strategies including emergency coronary interventions for patients with myocardial infarction accompanying suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection.

6)7)8) There are a few things to think about when treating suspected COVID-19 patients that are different from the traditional STEMI guidelines (

Figure 3). First, preparation for secondary infection control should precede treatment. If emergency procedures are performed without advance preparedness, there are greater risks of infection of medical staff and floor members who participated in the treatment. Prior to a procedure, isolation and COVID-19 testing of the target patient should always take place, and it is recommended that a secondary COVID-19 test be performed in the ICU after the procedure. Second, clinicians should consider whether and when to use fibrinolytics. Fibrinolytic therapy is one treatment option for relatively stable STEMI patients because appropriate treatment timing can be missed while time is spent preparing for coronary interventions in an emergency. However, it is recommended that the primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) be implemented as a priority treatment strategy in cases of cardiogenic shock, life-threatening arrhythmia, large ischemic burden myocardial infarction, or when there are contraindications of fibrinolytic therapy.

9) A comprehensive assessment that balances the risk-benefit ratio is needed to decide on a primary treatment strategy between PCI and thrombolysis.

| Figure 3

Proposed management algorithm for STEMI patients.

Cath Lab = catheterization laboratory; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ECG = electrocardiogram; HEPA = high-efficiency particulate air; ICU = intensive care unit; MI = myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; PPE = personal protective equipment; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

*Contraindication to thrombolytics: any previous history of hemorrhagic shock, ischemic stroke within 3 months, head trauma within 3 weeks or brain surgery within 6 months, known intracranial neoplasm, suspected aortic dissection, internal bleeding within 6 weeks, active bleeding or known bleeding disorder, traumatic cardiopulmonary resuscitation within 3 weeks. †High risk features: cardiogenic shock, life threatening arrhythmias, severe pulmonary edema, and large ischemic burden MI (e.g. anterior location).

|

Go to :

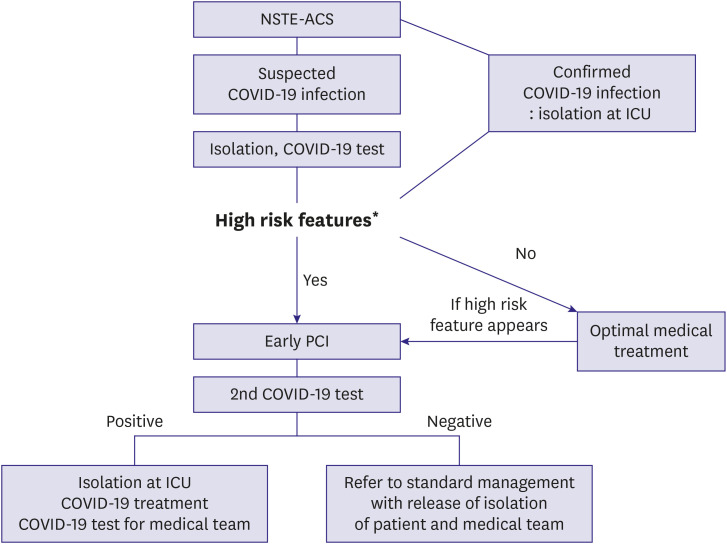

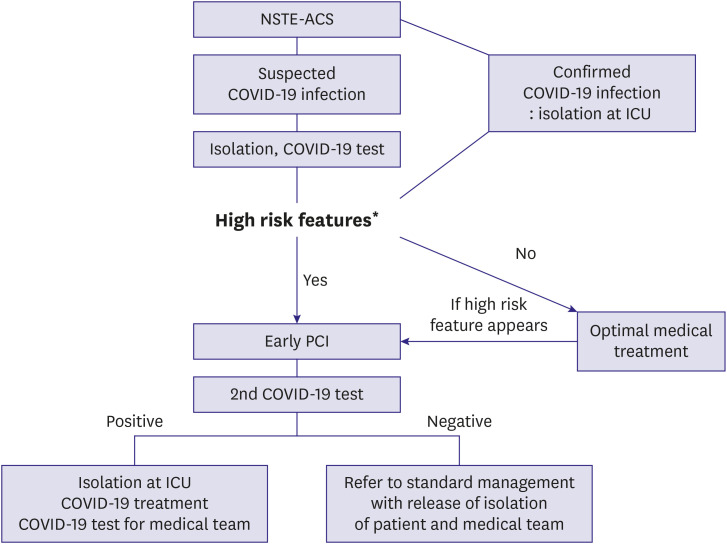

NON-ST-SEGMENT ELEVATION ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME

All non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) patients with suspected COVID-19 should be tested for the virus. For NSTE-ACS patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19, optimal medical treatment is recommended unless patients are showing high-risk features. A coping flow chart according to the condition of NSTE-ACS patients is shown in

Figure 4. High-risk features include hemodynamic instability, ongoing chest pain, life-threatening arrhythmia, and large ischemic burden MI. NSTE-ACS with high-risk features may be considered as STEMI.

4) It is also important to distinguish between type 2 MI and myocarditis, considering that recent reports suggest that acute cardiac injury is present in ≤7% of patients with COVID-19.

10)11)12)13)14)15) When an NSTE-ACS patient with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection must visit the Cath Lab, pre- and post-procedure isolation and tests for the virus are accomplished as for STEMI patients, as described above. Rapid discharge of patients after revascularization is recommended to maximize bed availability and reduce patient exposure within the hospital.

| Figure 4

Proposed management algorithm for NSTE-ACS patients.

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ICU = intensive care unit; MI = myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS = non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

*High risk features: cardiogenic shock, life-threatening arrhythmias, severe pulmonary edema, and large ischemic burden MI (e.g. anterior location).

|

Go to :

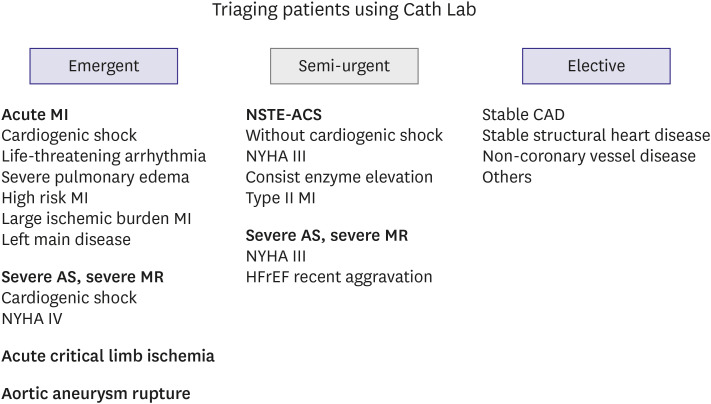

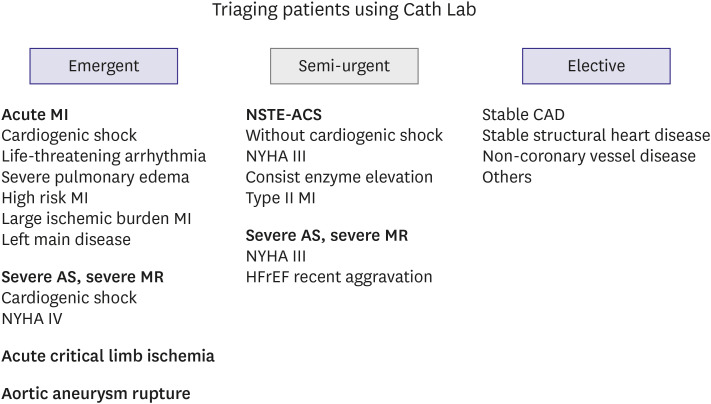

A ROADMAP FOR TRIAGING PATIENTS WHO REQUIRE INTERVENTION IN THE CATH LAB

In addition to AMI, mentioned above, there are many other cardiovascular disease cases that require intervention in the Cath Lab. It is important to consider whether treatment in the Cath Lab is truly necessary and to analyze the risk-benefit ratio for COVID-19 exposure. Most procedures for non-coronary artery disease should be delayed as elective treatment to preserve hospital bed capacity while visits for COVID-19 are at a peak. However, there are several cases where emergency procedures are required. For example, acute critical limb ischemia, impending aortic aneurysm rupture, and severe aortic stenosis with cardiogenic shock or New York Heart Association class IV symptoms need to be considered.

16) The triage scheme for patients with cardiovascular disease requiring Cath Lab work is shown in

Figure 5. Patients who may require emergency procedures at any time due to deterioration are classified as the semi-urgent group, and monitoring is required. This triaging is not intended to be all-encompassing but rather to provide general considerations with illustrative cases. If a new major symptom of COVID-19 appears, guidelines for COVID-19 testing, isolation, and wearing of protective gear should be applied.

| Figure 5

Triage of patients with cardiovascular disease requiring cardiovascular interventions.

AS = aortic stenosis; CAD = coronary artery disease; Cath Lab = catheterization laboratory; MI = myocardial infarction; MR = mitral regurgitation; NSTE-ACS = non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NYHA = New York Heart Association.

|

Go to :

CONCLUSION

The current COVID-19 crisis is causing an unprecedented disaster. We may be forced into a long-term, large-scale deprivation of medical services if contagion occurs in any medical facility. In this pandemic era, when we make a medical decision concerning patient management, we must consider securing medical resources and the safety of medical staff and the institution as a whole, not only the patient's risks and benefits.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the board members from the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology (KSIC) for supporting the development and amendment of these COVID-19 clinical practice guidelines for coronary intervention.

Go to :

Notes

Go to :

References

1. Choe PG, Kang EK, Lee SY, et al. Selecting coronavirus disease 2019 patients with negligible risk of progression: early experience from non-hospital isolation facility in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2020; 35:765–770. PMID:

32460457.

4. Lemkes JS, Janssens GN, van der Hoeven NW, et al. Coronary angiography after cardiac arrest without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:1397–1407. PMID:

30883057.

5. Rab T, Kern KB, Tamis-Holland JE, et al. Cardiac arrest: a treatment algorithm for emergent invasive cardiac procedures in the resuscitated comatose patient. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 66:62–73. PMID:

26139060.

6. Welt FGP, Shah PB, Aronow HD, et al. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: from the ACC's interventional council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 75:2372–2375. PMID:

32199938.

7. Galeazzi GL, Loffi M, Di Tano G, Danzi GB. Severe COVID-19 pneumonia and very late stent thrombosis: a trigger or innocent bystander? Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:632–633. PMID:

32588573.

8. Campo G, Rapezzi C, Tavazzi L, Ferrari R. Priorities for Cath labs in the COVID-19 tsunami. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:1784–1785. PMID:

32286606.

9. Armstrong PW, Gershlick AH, Goldstein P, et al. Fibrinolysis or primary PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:1379–1387. PMID:

23473396.

10. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020; 323:1061–1069. PMID:

32031570.

11. Deng Q, Hu B, Zhang Y, et al. Suspected myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19: evidence from front-line clinical observation in Wuhan, China. Int J Cardiol. 2020; 311:116–121. PMID:

32291207.

12. Zeng JH, Liu YX, Yuan J, et al. First case of COVID-19 complicated with fulminant myocarditis: a case report and insights. Infection. 2020.

13. Kochi AN, Tagliari AP, Forleo GB, Fassini GM, Tondo C. Cardiac and arrhythmic complications in patients with COVID-19. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020; 31:1003–1008. PMID:

32270559.

14. Danzi GB, Loffi M, Galeazzi G, Gherbesi E. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: a random association? Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:1858. PMID:

32227120.

15. Klok FA, Kruip MJ, van der Meer NJ, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020; 191:145–147. PMID:

32291094.

16. Shah PB, Welt FGP, Mahmud E, Phillips A, Anwaruddin S. Reply: triage considerations for patients referred for structural heart disease intervention during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an ACC/SCAI consensus statement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020; 13:1607–1608. PMID:

32646705.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download