DISCUSSION

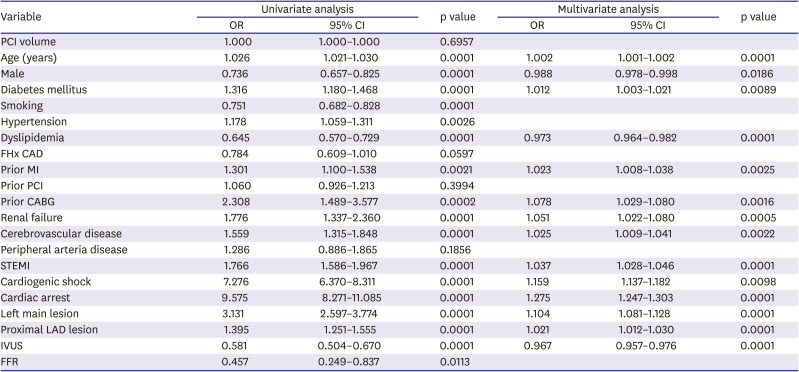

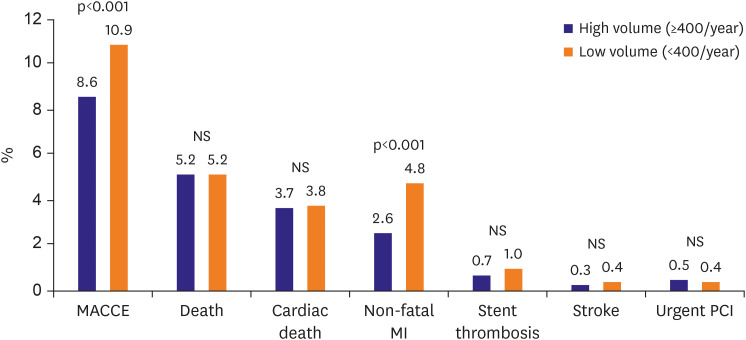

This study is the first large registry study to analyze relationships between hospital PCI volume and in-hospital clinical outcomes of patients with AMI that underwent PCI in Korea. The main results of the study were that the low-volume group had a higher frequency of overall MACCE and non-fatal MI than the high-volume group. However, hospital PCI volume did not affect mortality rates and was not found to predict MACCE independently.

The 2011 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention (ACCF/AHA/SCAI) guideline and the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society recommend a minimum annual hospital PCI volume of 400, but many rural hospitals in the USA do not meet this minimum requirement.

2)12)16)17) Similarly, more than 50% of Korea hospitals in the provinces do not perform ≥400 PCI procedures annually, but nevertheless, frequently provide important services such as early invasive treatment for NSTEMI and primary PCI for STEMI.

18)

The Paris Metropolitan PCI registry study (2001–2002) showed a clear inverse relationship exists between hospital PCI volume and in-hospital mortality after emergency procedures had been performed on patients presenting with AMI, cardiogenic shock, or out of hospital cardiac arrest (6.75% mortality at high-volume hospitals vs. 8.54% at low-volume hospitals, p=0.028). As was performed in the present study, the Paris Metropolitan PCI registry study divided the cohort into 2 groups based on hospital volumes of < or ≥400 PCI cases per annum.

6) The difference between the results of the 2 studies might be explained as follows. First, the 2 studies were conducted 13 years apart, and in our study, the transradial approach was used in >50%, and drug-eluting stents (DES) were implanted in >90% of our patients. Second, PCI devices advanced considerably during this period, for example, coronary stents were introduced and reduced the mortality disparity between low-volume and high-volume PCI hospitals.

7) Furthermore, new technologies like IVUS and FFR have been introduced, and PCI operators now have many opportunities to learn about PCI techniques at domestic and international live demonstration meetings and conferences.

19)20)21)

Most studies have compared low-volume and high-volume PCI hospitals with respect to primary PCI for STEMI. A Japanese study concluded no differences in mortality between AMI patients that had undergone primary PCI at low- vs. high-volume primary PCI hospitals (9.9% vs. 10.5%, p=0.688). However, other studies conducted in the US, France, and a meta-analysis concluded mortality rates are higher at low-volume PCI hospitals.

4)5)6)7)15)22)

The hospital PCI volume-outcome relationship has been discussed for a long time, which is not surprising because the findings of studies on the topic are discordant. These differences may have been caused by cohort heterogeneities in terms of CAD severity, concurrent diseases, methods of categorization, and the definition of PCI volume used.

A retrospective analysis of the database of the National Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service and Korean National Statistical Office failed to detect a difference in the risk-adjusted 30-day mortality rates after PCI between the low (<200 cases/year), medium (200–399 cases/year), and high (≥400 cases/year) volume hospitals.

23)

The 2013 ACCF/AHA/SCAI clinical competence statement eased minimum requirements for PCI to >200 procedures per annum for institutes and ≥50 procedures per annum for operators, and the 2014 PCI guidelines of the ESC/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery recommend a minimum of 75 procedures per year for operators.

24)25) A recent Japanese PCI (J-PCI) registry report showed the probability of mortality plateaued at approximately 100 procedures per year.

21) Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology (KSIC) certified hospitals are required to carry out at least 100 PCI cases each year, and thus, the study subjects were divided and compared using a cut-off of 100 PCI cases per year. Therefore, the occurrence of MACCE, death, and non-fatal MI was statistically higher in hospitals with less than 100 PCI cases per year (

Supplementary Figure 1). The results of the present study based on 2014 K-PCI registry data support the currently required minimum threshold of 100 PCI cases per year for the accreditation of institutes by the KSIC.

Currently, the KSIC recommends ≥150 PCI procedures every 2 years to meet interventional cardiologist certification requirements and ≥100 PCIs/year for an institute to be certified by the KSIC. However, in our opinion, the KSIC recommendation of ≥75 PCI procedures/year for each operator is over-demanding. Inohara et al.

21) reported that lower institutional PCI volume was inversely related to in-hospital outcomes. However, the predicted probability of mortality decreased with increasing institutional PCI volume and flattened out at approximately >100 procedures per year. The association between annual operator volume and outcomes was less clear in the J-PCI registry. Furthermore, the median numbers of cases per annum per Japanese and US operator have been reported to be 28 and 33, respectively.

9) However, we do not think the results of the J-PCI registry are much worse than those of the Korean K-PCI registry, and therefore, it would appear hospital PCI volume is more important than operator PCI volume.

In a recently published study, PCI hospitals were divided into 3 groups according to operator volume; the 75th percentile (>30 cases/year), between 75th and 25th percentiles (10–30 cases/year), and below the 25th percentile (<10 cases/year). The researchers reported that in-hospital clinical outcomes were not significantly dependent on operator volume, which was not found to predict adverse outcomes before discharge.

10) We suggest the number of PCI cases required by KSIC for certified interventional cardiologists be reduced based on the findings of the present study and those of other studies.

9)24)26)

The number of hospitals that perform fewer PCI cases is expected to gradually increase in Korea, as is the case in Japan. Even in low volume hospitals, at least 3 interventional cardiologists are required for primary PCI to treat STEMI patients, and thus, the number of operators who cannot perform 75 PCI cases/year will increase, and operators affiliated to low-volume centers are likely to give up KSIC certification. The 2013 ACCF/AHA/SCAI clinical competence statement has eased the minimum requirements for PCI performance (>200 PCIs per year per institute and ≥50 PCIs per year for operators) to reflect the recent decline in the number of PCIs performed.

24)27)28)

In the present study, about 75% of all AMI patients were treated at a high-volume PCI hospital, and the remainder were treated at a low-volume PCI hospital. Low-volume PCI hospitals in small and medium-sized cities continue to make major contributions to the treatment of AMI, and thus, continuous quality control of low-volume PCI hospitals is critical.

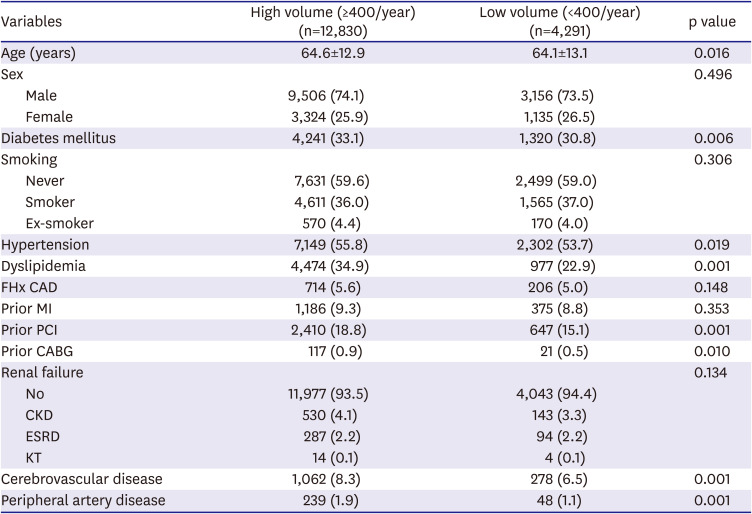

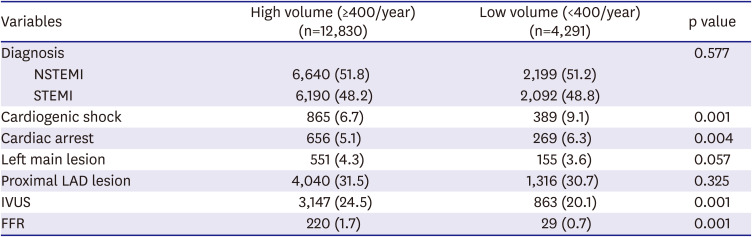

We found significant variations between high vs. low-volume PCI hospitals in terms of baseline clinical and procedural characteristics and in-hospital outcomes. Furthermore, rates of atherosclerosis risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidemia, and histories of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease were higher in high-volume PCI hospitals. This concurs with that found in a study registered in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry conducted from July 1, 2009, to March 31, 2015, which showed high-risk CAD patients are more likely to visit high-volume PCI hospitals.

29) Although no difference was observed between STEMI or NSTEMI rates among cases treated at high or low-volume hospitals, initial presentations of cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest were found to be more common for low-volume PCI hospitals. These results differ from those of the Paris Metropolitan PCI registry study, in which rates of cardiogenic shock were similar for high and low-volume PCI hospitals, and the cardiac arrest rate was lower for low-volume PCI hospitals.

We compared patients in the 2 study groups that presented with cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest. Baseline characteristics revealed no difference in clinical characteristics except for a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia in the high-volume group. Like that observed for all study subjects, a greater proportion of patients with cardiogenic shock were treated in low-volume hospitals. However, there was no difference in the proportion of cardiac arrest, left main lesion, proximal LAD lesion, and using IVUS and FFR in the patients with cardiogenic shock and arrest between 2 groups. In addition, MACCE rates were similar in the 2 groups.

Several recent clinical trials and one meta-analysis have reported that IVUS guidance PCI significantly decreased MACE, death, and stent thrombosis rates in patients with complex lesions or acute coronary syndrome.

19)30) We found IVUS was used more frequently in the high-volume group, and examined whether its use independently predicted MACCE. Multivariate analysis revealed that implementation of IVUS significantly reduced MACCE. Therefore, we cautiously suggest that increasing IVUS use during PCI in low-volume hospitals would reduce MACCE rates.

Technical issues are also important in terms of reducing MACCE rates after PCI, and according to a recent study based on 2014 K-PCI registry data, low volume PCI operators tend to experience higher rates of repeated PCI,

10) which indicates technical issues are importantly associated with the rate of non-fatal MI after PCI.

Emergency PCI for AMI is being implemented in low volume PCI hospitals in rural areas and small-sized private hospitals in Korea. KSIC accreditation of high-quality hospitals and implementation of the interventional cardiologist accreditation system have led to significant improvements in the skills of doctors and catheterization room staff in low-volume PCI hospitals. Also, recently developed coronary PCI devices such as DES and PCI with IVUS guidance have effectively reduced MACCE rates, and thus, nowadays, the effects of hospital PCI volumes on outcomes may be substantially attenuated, which we propose is a reason why hospital PCI volume was not found to independently predict MACCE in the present study. We suggest that hospital and operator accreditation requirements could be eased in Korea to less than minimum 2013 ACCF/AHA/SCAI requirements (>200 PCIs per year per institute and ≥50 PCIs per year for operators). However, to do so, a well-planned prospective study is needed to confirm the relationship between hospital PCI volume and in-hospital outcomes after the treatment of AMI in Korea.

The present study has a number of limitations that warrant consideration. First, only the 92 hospitals that participated in the 2014 K-PCI registry study were included. Therefore, we need to be careful in incorporating our study findings into all of the PCI hospitals and patients in Korea. Nevertheless, the hospitals that participated were recognized by KSIC and most university hospitals participated. Second, the study was based on registry data, which raises the possibility of input bias as individual institutions submitted data. However, the K-PCI data management and inspection program determined whether collected data were accurate and complete, and CRF variables were refined based on the results obtained. The 2014 K-PCI committee also performed data management quality verification during data collection. Third, we could not take into account the experience of operators at low- or high-volume PCI centers, and did not analyze in-hospital outcomes according to the number of procedures performed annually by operators. Forth, we used in-hospital outcomes as the study endpoint, and thus, a long-term follow-up study is needed to confirm the relationship between hospital PCI volumes and long-term clinical outcomes. Lastly, in-hospital clinical outcomes could not be compared concerning the presence or absence of cardiac intensive care teams and facilities because the K-PCI registry did not collect such data from each study participated hospitals.

In conclusion, this is the first Korean study to evaluate the relationship between hospital PCI volume and in-hospital clinical outcomes after PCI for AMI patients using 2014 K-PCI registry data. The study shows MACCE and non-fatal MI rates were higher at low-volume PCI hospitals, but that hospital PCI volume did not independently predict in-hospital outcomes.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download