|

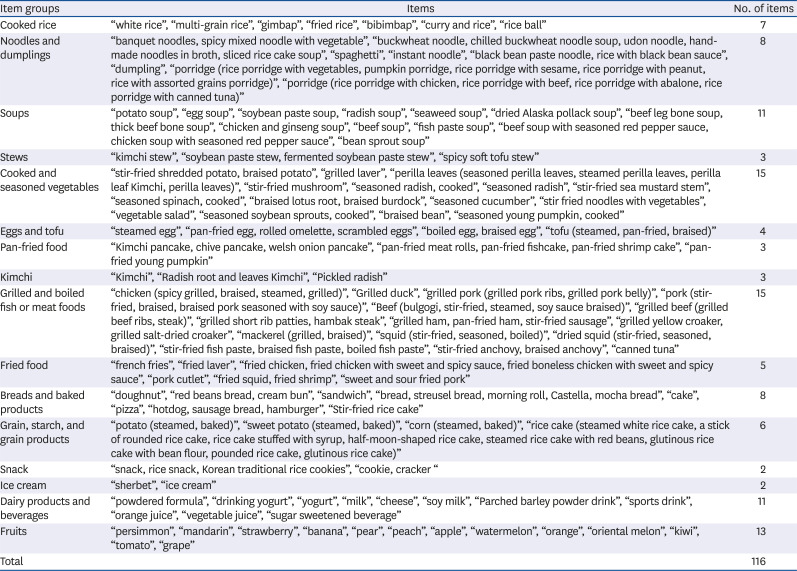

Cooked rice |

“white rice”, “multi-grain rice”, “gimbap”, “fried rice”, “bibimbap”, “curry and rice”, “rice ball” |

7 |

|

Noodles and dumplings |

“banquet noodles, spicy mixed noodle with vegetable”, “buckwheat noodle, chilled buckwheat noodle soup, udon noodle, hand-made noodles in broth, sliced rice cake soup”, “spaghetti”, “instant noodle”, “black bean paste noodle, rice with black bean sauce”, “dumpling”, “porridge (rice porridge with vegetables, pumpkin porridge, rice porridge with sesame, rice porridge with peanut, rice with assorted grains porridge)”, “porridge (rice porridge with chicken, rice porridge with beef, rice porridge with abalone, rice porridge with canned tuna)” |

8 |

|

Soups |

“potato soup”, “egg soup”, “soybean paste soup, “radish soup”, “seaweed soup”, “dried Alaska pollack soup”, “beef leg bone soup, thick beef bone soup”, “chicken and ginseng soup”, “beef soup”, “fish paste soup”, “beef soup with seasoned red pepper sauce, chicken soup with seasoned red pepper sauce”, “bean sprout soup” |

11 |

|

Stews |

“kimchi stew”, “soybean paste stew, fermented soybean paste stew”, “spicy soft tofu stew” |

3 |

|

Cooked and seasoned vegetables |

“stir-fried shredded potato, braised potato”, “grilled laver”, “perilla leaves (seasoned perilla leaves, steamed perilla leaves, perilla leaf Kimchi, perilla leaves)”, “stir-fried mushroom”, “seasoned radish, cooked”, “seasoned radish”, “stir-fried sea mustard stem”, “seasoned spinach, cooked”, “braised lotus root, braised burdock”, “seasoned cucumber”, “stir fried noodles with vegetables”, “vegetable salad”, “seasoned soybean sprouts, cooked”, “braised bean”, “seasoned young pumpkin, cooked” |

15 |

|

Eggs and tofu |

“steamed egg”, “pan-fried egg, rolled omelette, scrambled eggs”, “boiled egg, braised egg”, “tofu (steamed, pan-fried, braised)” |

4 |

|

Pan-fried food |

“Kimchi pancake, chive pancake, welsh onion pancake”, “pan-fried meat rolls, pan-fried fishcake, pan-fried shrimp cake”, “pan-fried young pumpkin” |

3 |

|

Kimchi |

“Kimchi”, “Radish root and leaves Kimchi”, “Pickled radish” |

3 |

|

Grilled and boiled fish or meat foods |

“chicken (spicy grilled, braised, steamed, grilled)”, “Grilled duck”, “grilled pork (grilled pork ribs, grilled pork belly)”, “pork (stir-fried, braised, braised pork seasoned with soy sauce)”, “Beef (bulgogi, stir-fried, steamed, soy sauce braised)”, “grilled beef (grilled beef ribs, steak)”, “grilled short rib patties, hambak steak”, “grilled ham, pan-fried ham, stir-fried sausage”, “grilled yellow croaker, grilled salt-dried croaker”, “mackerel (grilled, braised)”, “squid (stir-fried, seasoned, boiled)”, “dried squid (stir-fried, seasoned, braised)”, “stir-fried fish paste, braised fish paste, boiled fish paste”, “stir-fried anchovy, braised anchovy”, “canned tuna” |

15 |

|

Fried food |

“french fries”, “fried laver”, “fried chicken, fried chicken with sweet and spicy sauce, fried boneless chicken with sweet and spicy sauce”, “pork cutlet”, “fried squid, fried shrimp”, “sweet and sour fried pork” |

5 |

|

Breads and baked products |

“doughnut”, “red beans bread, cream bun”, “sandwich”, “bread, streusel bread, morning roll, Castella, mocha bread”, “cake”, “pizza”, “hotdog, sausage bread, hamburger”, “Stir-fried rice cake” |

8 |

|

Grain, starch, and grain products |

“potato (steamed, baked)”, “sweet potato (steamed, baked)”, “corn (steamed, baked)”, “rice cake (steamed white rice cake, a stick of rounded rice cake, rice cake stuffed with syrup, half-moon-shaped rice cake, steamed rice cake with red beans, glutinous rice cake with bean flour, pounded rice cake, glutinous rice cake)” |

6 |

|

Snack |

“snack, rice snack, Korean traditional rice cookies”, “cookie, cracker “ |

2 |

|

Ice cream |

“sherbet”, “ice cream” |

2 |

|

Dairy products and beverages |

“powdered formula”, “drinking yogurt”, “yogurt”, “milk”, “cheese”, “soy milk”, “Parched barley powder drink”, “sports drink”, “orange juice”, “vegetable juice”, “sugar sweetened beverage” |

11 |

|

Fruits |

“persimmon”, “mandarin”, “strawberry”, “banana”, “pear”, “peach”, “apple”, “watermelon”, “orange”, “oriental melon”, “kiwi”, “tomato”, “grape” |

13 |

|

Total |

|

116 |

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download