This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

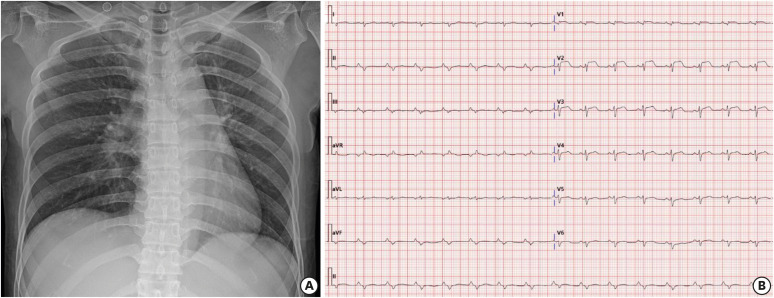

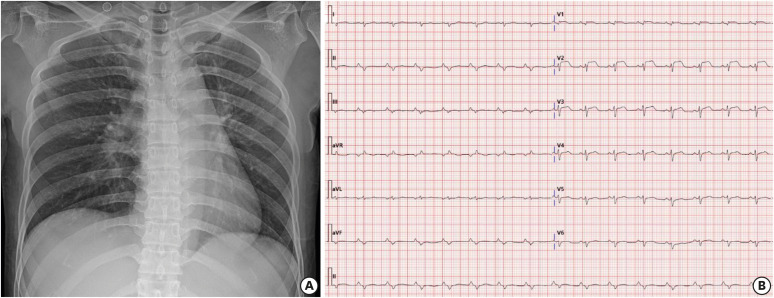

A 42-year-old female without previous medical history visited for febrile sensation, myalgia, and shortness of breath for two days. Her entrance to the emergency room (ER) was delayed due to the triage process during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak. Mild cardiomegaly with left atrial enlargement on chest X-ray and ST-elevation on electrocardiography were noted (

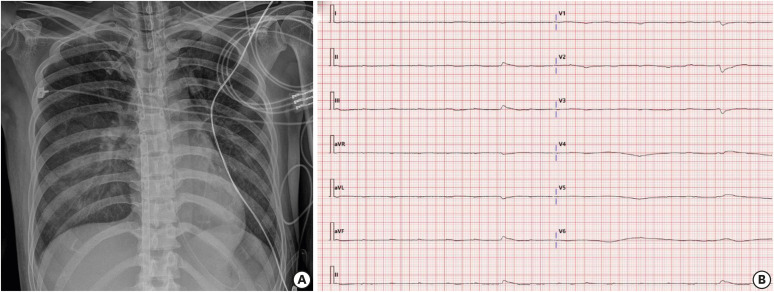

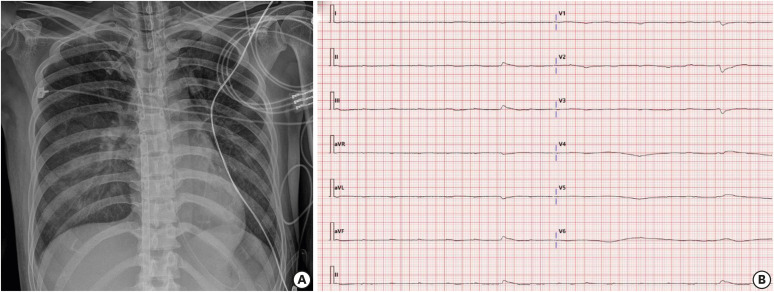

Figure 1). Sudden cardiac arrest developed at ER and immediate extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was applied. No coronary obstruction was present. The test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) was negative and the repeated tests consistently showed negative results. On post-admission day 5, there was only p wave without corresponding ventricular conduction on electrocardiography (

Figure 2) which was correlated with echocardiographic finding (

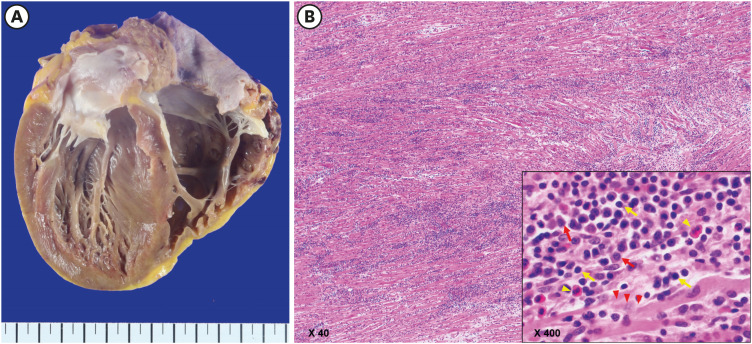

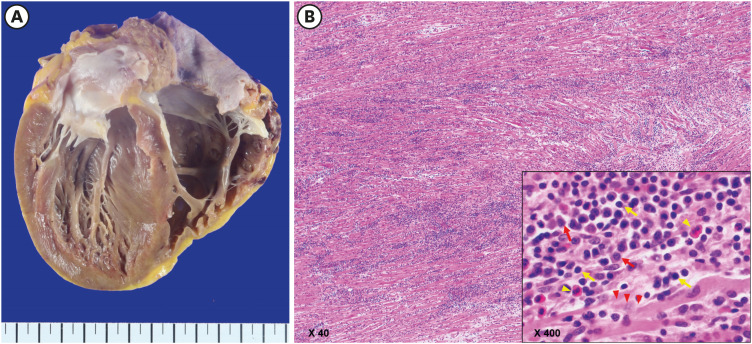

Supplementary Video 1). We put the patient for heart transplantation (HT) waitlist due to the aggravating course of fulminant myocarditis. Three days later, a 27-year-old male donor was matched with negative crossmatch result. The donor test of SARS-CoV-2 revealed negative. The hospital organ procurement organization in other region hesitated to allow the procurement team from the city (Daegu) where the COVID-19 outbreak was prevalent due to the concern of SARS-CoV-2 spread. Our procurement team decided to take a nasopharyngeal swab to prove negative of SARS-CoV-2 infection before the departure. After the confirmation of the negative result, successful HT could be performed. Explanted heart showed extensive myocyte damage corresponding to her grave course (

Figure 3). She was managed in the positive pressure isolation room with the complete isolation from the COVID-19 patients in the negative pressure isolation room located on the different floor. The essence of successful HT is to maintain the best level of mutual co-operation between organizations.

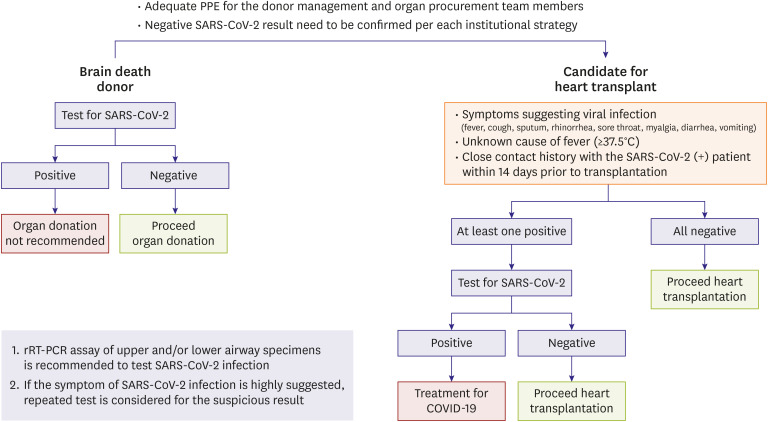

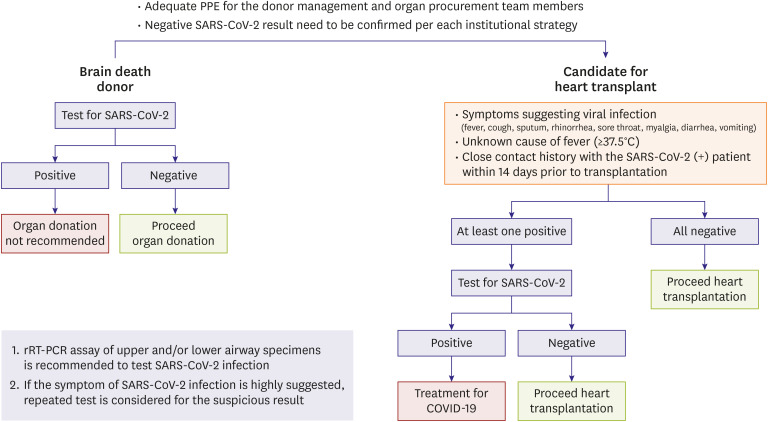

1) During the outbreak of COVID-19, a balanced strategy to ensure the safety of HT recipient and medical staff is crucial in the consideration of each individual circumstance (

Figure 4).

1)-5)

| Figure 1Anteroposterior chest radiography (A), electrocardiography (B) on first presentation. The chest radiography shows mild cardiomegaly with flattening of left cardiac border suggesting left atrial enlargement (A), and electrocardiography shows sinus rhythm with a nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay and ST-segment elevation in precordial leads (B).

|

| Figure 2Anteroposterior chest radiography (A), electrocardiography (B) on post-admission day 5. The chest radiography and computed tomography shows slightly decreased cardiac size with increased both lung congestion after the extracorporeal membrane oxygenator apply (A), and electrocardiography shows a few faint ventricular escape rhythm with non-conducted baseline p waves (B).

|

| Figure 3Gross specimen and microscopic findings of the explanted heart. Gross specimen shows enlarged ventricular chambers (A), and H&E stain shows lymphocyte dominant with plasma cell and eosinophil infiltration (lymphocyte – yellow arrow, plasma cell – red arrow, eosinophil – yellow arrowhead) and diffuse myocyte damage (red arrowhead) compatible with fulminant myocarditis by Dallas criteria (B).

|

| Figure 4

Algorithm of the SARS-CoV-2 Test Strategy for the brain death donor and candidate for heart transplantation during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain death donors should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection (preferably rRT-PCR assay from upper and/or lower respiratory tract specimens). If the test result is negative, organ donation can be safely proceeded. When the heart transplantation recipient has symptoms suggesting viral infection, unknown cause of fever, or close contact history with the SARS-CoV-2 infected patients prior 14 days, test for SARS-CoV-2 infection should be performed and proceed heart transplantation when the result is negative. Members of the donor management team and the organ procurement team should apply adequate personal protective equipment. Confirmation of the negative SARS-CoV-2 result need to be ensured according to the strategy of each hospital organ procurement organization. If the symptom of SARS-CoV-2 infection is highly suggested, repeated test need to be performed for the suspicious result.

SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; rRT-PCR = real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; PPE = personal protective equipment.

|

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download