INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) has a high prevalence and a poor prognosis, and the medical costs for treating HF patients are also enormous, which is a huge burden on people worldwide.

1)2) Although recent advancement in drugs and devices allows patients with HF to live longer,

3)4) HF prognosis is still poor, not as good as that of cancer.

5)6)7) Therefore, further strategies are always needed to improve HF prognosis. For the effective treatment and prognosis improvement of HF, medical staffs as well as the general public should first be familiar with HF. However, even though HF is serious, the public awareness of HF reported in a small number of studies is very low. Since 1990, a little research on HF awareness in the general public has been conducted mostly in Europe.

8)9)10)11) As a consistent result, the recognition rate of HF was very low in the general population. In Asia, HF patients also continue to grow and health care costs are increasing, but no study of HF awareness has been conducted except for one of our studies.

12) Recently, our group published an article on HF awareness in the general population of Korea, and showed that the public's HF awareness was still low.

12) To be more specific, although 80% of the participants had heard of HF, only 47% exactly defined what HF was. A minority of participants correctly recognized the lifetime risk of developing HF (21%) as well as the mortality (16%)/readmission risk (18%) of HF and the cost burden of HF admission (28%). These differences in severity and perception of HF can eventually slow treatment and worsen the prognosis of HF patients.

13) Therefore, it is important to find out the factors related to HF awareness in order to improve it. With this background, this study was performed to investigate to find out which demographic features would be associated with low HF awareness in the general population of Korea.

RESULTS

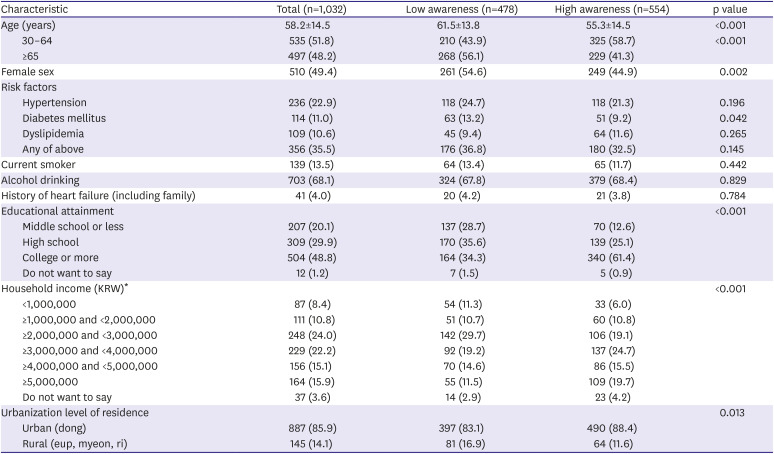

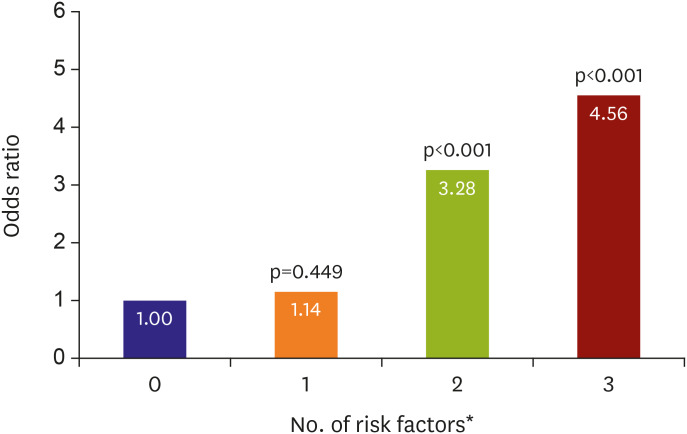

The characteristics of the study subjects are demonstrated in

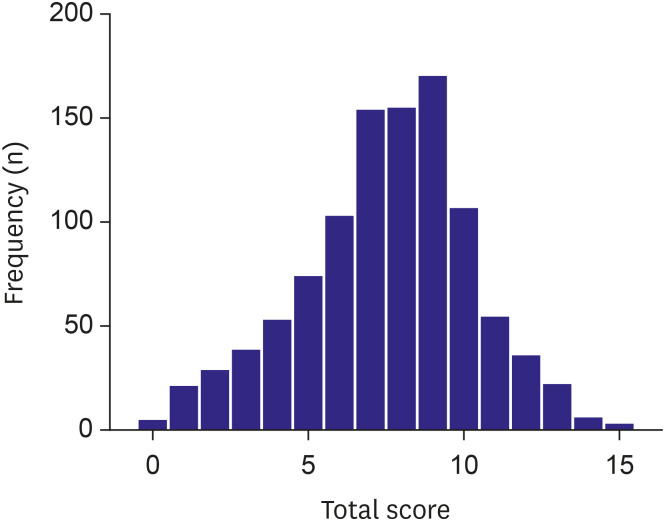

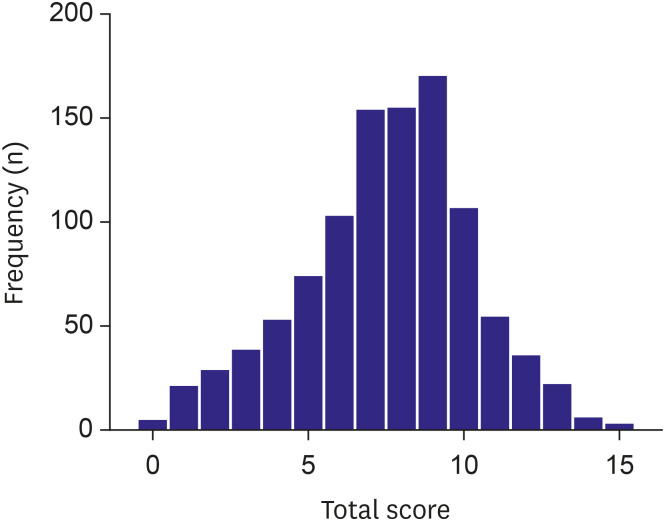

Table 1. In the total study population, mean age was 58.2±14.5 years, and about half (48.2%) of them were elderly (≥65 years). The male to female ratio was similar (female, 49.4%). The proportions of subjects with hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia were 22.9%, 11.0%, and 10.6%, respectively. The proportions of subjects with cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking were 13.5% and 68.1%, respectively. There were 41 subjects (4.0%) having a history of HF in themselves or in their family members. About half (48.8%) had college or higher educational status, 43.2% had monthly household income of less than 3 million Korean won (KRW), and 14.1% living in rural areas. In the survey results for 15 questions, the mean score was 7.53±2.75 points and the median score was 8 points. The score distribution is shown in

Figure 1. The subjects were divided into 2 groups, based on this median value of score, high awareness group (score ≥8, n=554) and the low awareness group (score <8, n=478). We compared clinical characteristics between the 2 groups (

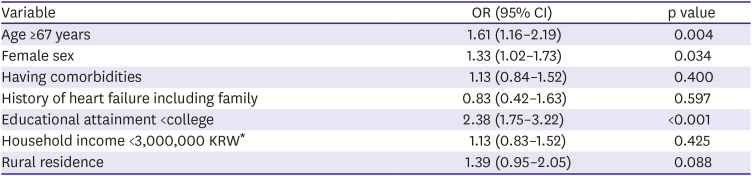

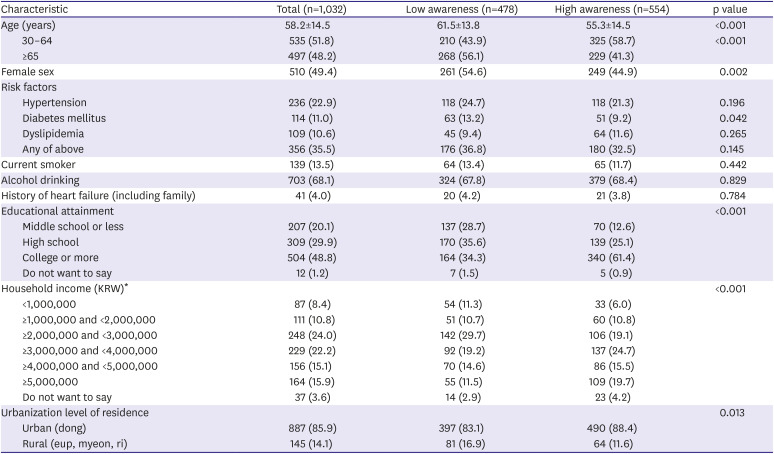

Table 1). Subjects with low awareness were older and more female-dominant. More subjects had diabetes mellitus in low awareness group than in the high awareness group. Subjects with low awareness had lower levels of education and income, and higher rates of living in rural areas than those with high awareness. In ROC curve analysis, the cut-off value of age in the best prediction of low HF awareness was 67 years (sensitivity, 74.2%; specificity, 45.6%; area under curve, 0.742; p<0.001). The results of multivariable analysis on independent risk factors for low HF awareness are shown in

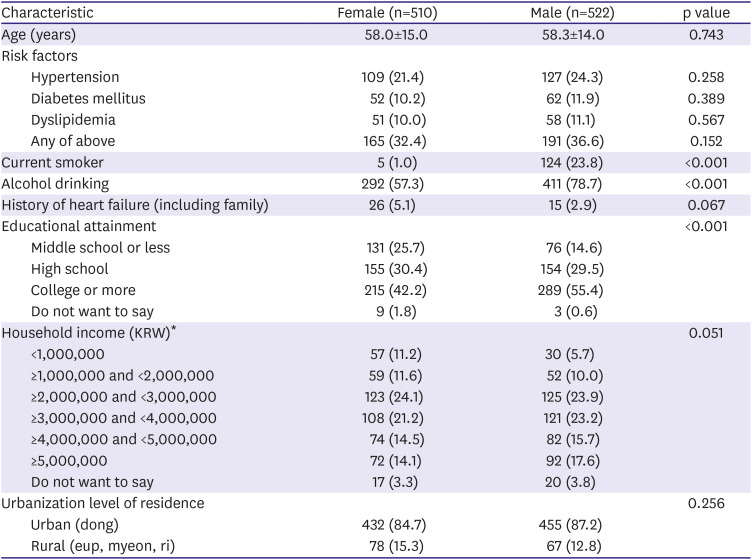

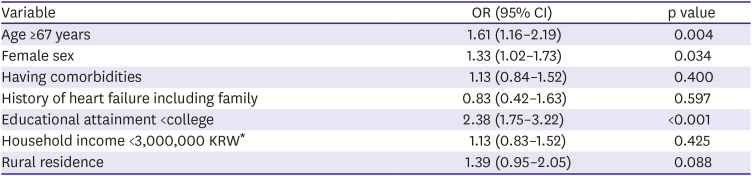

Table 2. Age (≥67 vs. <67 years: OR, 1.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.16–2.19; p=0.004), female sex (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.02–1.73; p=0.034), and low educational level (high school graduate or less vs. college graduate: OR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.75–3.22; p<0.001) were associated with low HF awareness even after controlling for potential confounders. Cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking were less frequently observed in females than in males. Females were less educated than males (

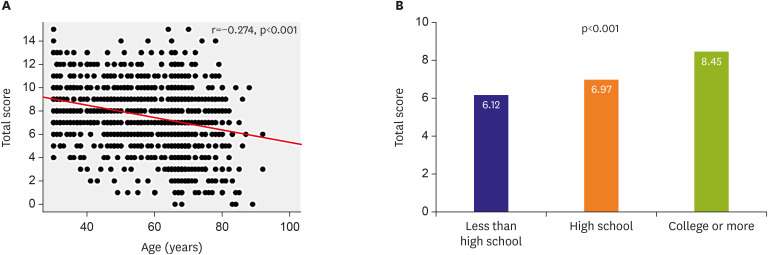

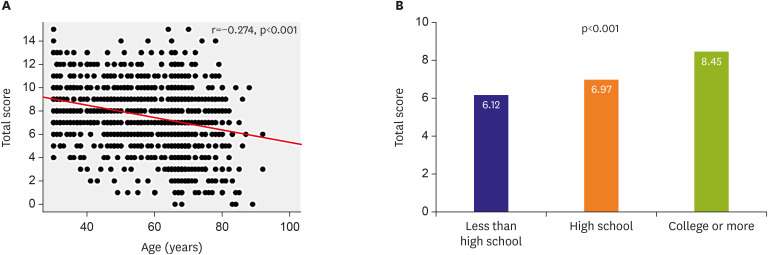

Table 3). The associations of the score of HF awareness with age (

r=−0.274; p<0.001) and educational level (p<0.001) are demonstrated in

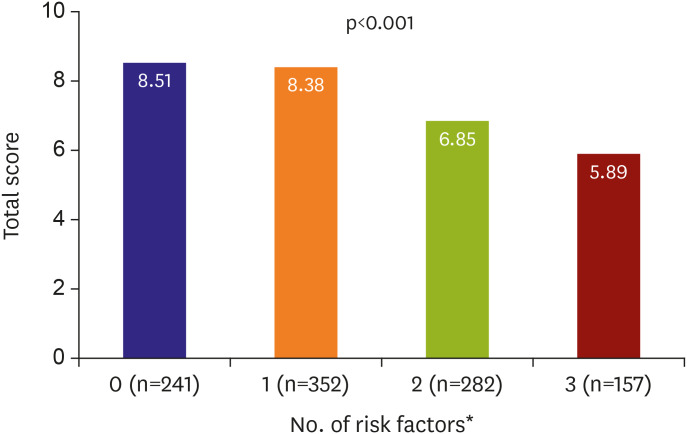

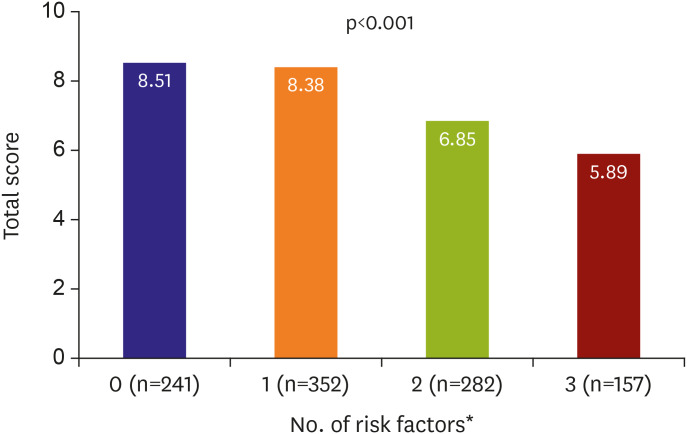

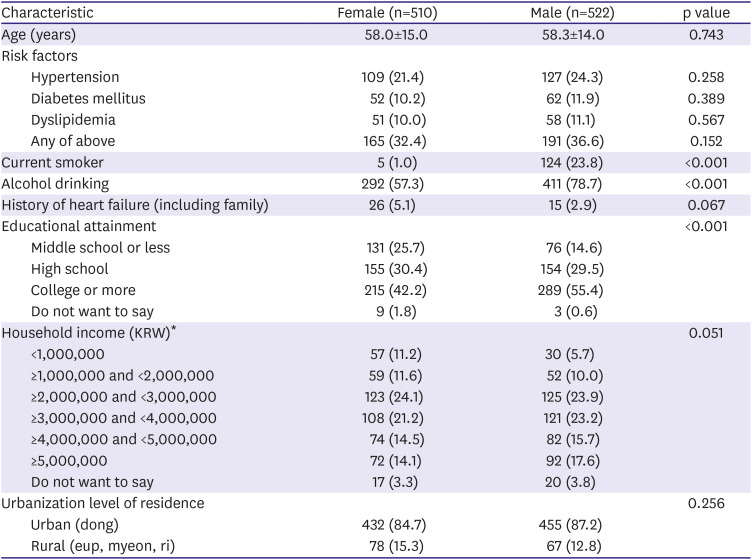

Figure 2. In regard to the 3 risk factors, old age (≥67 years), female sex and low education level (high school or less) showing statistical significance in multivariable analysis, the number of risk factors increased with decreasing score of HF awareness (p<0.001) (

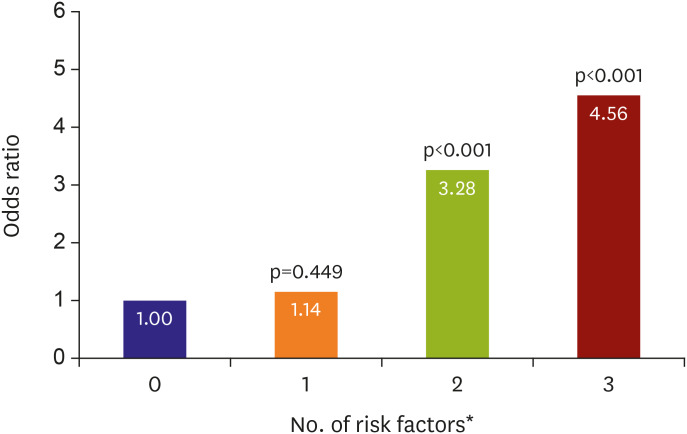

Figure 3). The score of HF awareness was significantly higher in subjects with ≤1 risk factor than those with 2 or 3 risk factors (6.47±2.88 vs. 8.42±2.27; p<0.001). With increasing the number of risk factors, OR for low HF awareness increased (OR for subjects with 2 risk factors compared to those with no risk factors; 3.28; p<0.001; OR for those with 3 risk factors compared to those with no risk factors; 4.56; p<0.001) (

Figure 4). When we stratified study subjects into 3 groups according to their awareness scores (<7 vs. 7–9 vs. ≥10), older age, female sex and lower educational level were also associated with lower HF awareness (score <7), which is the same finding to result obtained from the 2-group analysis (

Supplementary Tables 2 and

3).

Figure 1

Distribution of heart failure awareness score.

Figure 2

Associations of heart failure awareness score with age (A) and education levels (B).

Figure 3

Association between number of risk factors and heart failure awareness score.

*Risk factors includes old age (≥67 years), female sex and low education level (high school or less).

Figure 4

Odds ratio for low heart failure awareness according to the number of risk factors.

*Risk factors includes old age (≥67 years), female sex and low education level (high school or less). The p values are obtained from the comparison with group with no risk factor.

Table 1

Characteristics of survey responders

|

Characteristic |

Total (n=1,032) |

Low awareness (n=478) |

High awareness (n=554) |

p value |

|

Age (years) |

58.2±14.5 |

61.5±13.8 |

55.3±14.5 |

<0.001 |

|

30–64 |

535 (51.8) |

210 (43.9) |

325 (58.7) |

<0.001 |

|

≥65 |

497 (48.2) |

268 (56.1) |

229 (41.3) |

|

Female sex |

510 (49.4) |

261 (54.6) |

249 (44.9) |

0.002 |

|

Risk factors |

|

|

|

|

|

Hypertension |

236 (22.9) |

118 (24.7) |

118 (21.3) |

0.196 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

114 (11.0) |

63 (13.2) |

51 (9.2) |

0.042 |

|

Dyslipidemia |

109 (10.6) |

45 (9.4) |

64 (11.6) |

0.265 |

|

Any of above |

356 (35.5) |

176 (36.8) |

180 (32.5) |

0.145 |

|

Current smoker |

139 (13.5) |

64 (13.4) |

65 (11.7) |

0.442 |

|

Alcohol drinking |

703 (68.1) |

324 (67.8) |

379 (68.4) |

0.829 |

|

History of heart failure (including family) |

41 (4.0) |

20 (4.2) |

21 (3.8) |

0.784 |

|

Educational attainment |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

Middle school or less |

207 (20.1) |

137 (28.7) |

70 (12.6) |

|

High school |

309 (29.9) |

170 (35.6) |

139 (25.1) |

|

College or more |

504 (48.8) |

164 (34.3) |

340 (61.4) |

|

Do not want to say |

12 (1.2) |

7 (1.5) |

5 (0.9) |

|

Household income (KRW)*

|

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

<1,000,000 |

87 (8.4) |

54 (11.3) |

33 (6.0) |

|

≥1,000,000 and <2,000,000 |

111 (10.8) |

51 (10.7) |

60 (10.8) |

|

≥2,000,000 and <3,000,000 |

248 (24.0) |

142 (29.7) |

106 (19.1) |

|

≥3,000,000 and <4,000,000 |

229 (22.2) |

92 (19.2) |

137 (24.7) |

|

≥4,000,000 and <5,000,000 |

156 (15.1) |

70 (14.6) |

86 (15.5) |

|

≥5,000,000 |

164 (15.9) |

55 (11.5) |

109 (19.7) |

|

Do not want to say |

37 (3.6) |

14 (2.9) |

23 (4.2) |

|

Urbanization level of residence |

|

|

|

0.013 |

|

Urban (dong) |

887 (85.9) |

397 (83.1) |

490 (88.4) |

|

Rural (eup, myeon, ri) |

145 (14.1) |

81 (16.9) |

64 (11.6) |

Table 2

Independent risk factors for low awareness

|

Variable |

OR (95% CI) |

p value |

|

Age ≥67 years |

1.61 (1.16–2.19) |

0.004 |

|

Female sex |

1.33 (1.02–1.73) |

0.034 |

|

Having comorbidities |

1.13 (0.84–1.52) |

0.400 |

|

History of heart failure including family |

0.83 (0.42–1.63) |

0.597 |

|

Educational attainment <college |

2.38 (1.75–3.22) |

<0.001 |

|

Household income <3,000,000 KRW*

|

1.13 (0.83–1.52) |

0.425 |

|

Rural residence |

1.39 (0.95–2.05) |

0.088 |

Table 3

Characteristics of survey responders according to sex

|

Characteristic |

Female (n=510) |

Male (n=522) |

p value |

|

Age (years) |

58.0±15.0 |

58.3±14.0 |

0.743 |

|

Risk factors |

|

|

|

|

Hypertension |

109 (21.4) |

127 (24.3) |

0.258 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

52 (10.2) |

62 (11.9) |

0.389 |

|

Dyslipidemia |

51 (10.0) |

58 (11.1) |

0.567 |

|

Any of above |

165 (32.4) |

191 (36.6) |

0.152 |

|

Current smoker |

5 (1.0) |

124 (23.8) |

<0.001 |

|

Alcohol drinking |

292 (57.3) |

411 (78.7) |

<0.001 |

|

History of heart failure (including family) |

26 (5.1) |

15 (2.9) |

0.067 |

|

Educational attainment |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

Middle school or less |

131 (25.7) |

76 (14.6) |

|

High school |

155 (30.4) |

154 (29.5) |

|

College or more |

215 (42.2) |

289 (55.4) |

|

Do not want to say |

9 (1.8) |

3 (0.6) |

|

Household income (KRW)*

|

|

|

0.051 |

|

<1,000,000 |

57 (11.2) |

30 (5.7) |

|

≥1,000,000 and <2,000,000 |

59 (11.6) |

52 (10.0) |

|

≥2,000,000 and <3,000,000 |

123 (24.1) |

125 (23.9) |

|

≥3,000,000 and <4,000,000 |

108 (21.2) |

121 (23.2) |

|

≥4,000,000 and <5,000,000 |

74 (14.5) |

82 (15.7) |

|

≥5,000,000 |

72 (14.1) |

92 (17.6) |

|

Do not want to say |

17 (3.3) |

20 (3.8) |

|

Urbanization level of residence |

|

|

0.256 |

|

Urban (dong) |

432 (84.7) |

455 (87.2) |

|

Rural (eup, myeon, ri) |

78 (15.3) |

67 (12.8) |

DISCUSSION

Using the telephone survey data from the whole country, we sought to find out factors associated with low HF awareness in the general public in Korea. Our main finding showed that older age, female sex and lower educational level were independently associated with low HF awareness in the general Korean population. As increased number of these risk factors, HF awareness score decreased and the risk of low HF awareness increased proportionally. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study primarily focusing on factors that predict low HF awareness.

There are several studies on HF awareness in the general public. Perhaps the Study of Heart failure Awareness and Perception in Europe (SHAPE) study was the first step in the study of HF awareness.

8)15) The SHAPE study conducted a survey of about 8,000 subjects in 9 European countries, and demonstrated low HF awareness in the general population. In that study, only 3% of the subjects were able to correctly identify HF from a description of typical symptoms and signs; on the other hand, 31% correctly identified angina, and 51% identified transient ischemic attack/stroke.

8) In a study of 850 subjects who visited the European Heart Failure Awareness Day 2011 event in Slovenia, the public's HF awareness was also low. The study results showed that HF was perceived as less important than cancer, myocardial infarction, stroke and diabetes with only 6%, 12%, 7%, and 5% of subjects ranking HF as number 1 in terms of prevalence, cost, quality of life, and survival, respectively.

9) A survey study of 2,438 subjects conducted in 4 European countries, showed that 31% considered HF as a normal condition at older ages, and only 38% realized the particularly poor prognosis after HF hospitalization.

14) A more recent study in Germany reported that only 40% of the study subjects knew about HF symptoms such as shortness of breath, reduced exercise tolerance and leg edema.

10) A study of the elderly in the United States found that approximately 70% of the subjects had incorrect understanding of the term “HF” and thought it meant that the heart had actually stopped working.

16) Most recently, our group also indicated that HF awareness remained poor in the general Korean population. Specifically, more than half of the participants (59%) thought that HF patients should live quietly and reduce all physical activities.

12) Most of the studies mentioned consistently emphasized the low HF awareness in the public, but did not analyze which risk factors are associated with low HF awareness. Azhar et al.

16) addressed that low HF awareness was associated with male sex, non-Hispanic race and low educational level; however, the number of the subjects enrolled was small (n=182), study participants were limited to the elderly, and multivariable analysis was not performed. In our previous study,

12) several survey questions were analyzed in respect to the socio-economic factors; however, only few survey items were addressed separately with univariable comparisons. In this context, we believe that the present study is valuable and noteworthy in that it summed 15 scorable survey questions and focused on clinical factors associated with low HF awareness using multivariable analysis.

Campaigns to raise HF awareness have been conducted in many countries around the world. In 2010, the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology launched the Heart Failure Awareness Day to initiate public campaigns about HF awareness across Europe. Since then, each year, the Heart Failure Awareness Campaign has been performed in various ways such as public lectures, opening of HF clinics, surveys, panel discussions, and promotion using media and social media. The Heart Failure Society of America also holds Heart Failure Awareness Week every February to improve HF awareness. The campaign aims to promote self-health awareness by encouraging regular checkups, educating about the signs and symptoms of HF, providing information on diet and exercise, and stressing the importance of regular screenings. In Korea, Korean Society of Heart Failure set HF week during every March, and is making efforts to raise HF awareness through various activities such as press conference, release of viral videos, public lecture, education and survey on HF. Links to the campaign homepages to improve HF awareness worldwide are listed in

Supplementary Data 1. Also, there were several articles on HF awareness based on survey results during campaign.

9)10)11) As it is expected that high HF awareness can lead to early diagnosis and treatment and eventually improved clinical outcomes, various efforts are being made around the world to improve HF awareness. However, there is a lack of evidence that these efforts actually improved HF awareness. Prospective research would be ideal for seeing which people can get a good clinical outcome by increasing HF awareness. Additional longitudinal studies are needed to clarify this. In this context, we think that our study deserves clinical attention because we identified risk factors for low HF awareness, and suggested the need of social attention and concentration on people with these risk factors to improve HF awareness. Ultimately it will lead to a better outcome.

Our study showed that age, female sex, and lower educational level were factors associated with low HF awareness. From a general point of view, it makes sense that the older and the lower the educational level, the lower the HF awareness. In our study, a lower educational level may have led to lower HF awareness in women than in men (

Table 3).

It is important to be aware of HF first to improve patients' outcome by quick diagnosis and appropriate treatment of HF.

2)13)17) Nevertheless, little research has been conducted on HF awareness. There have been only a few studies on HF awareness centered on Europe, but most were just descriptions of low HF awareness.

8)9)10)11) Although these studies suggested that efforts are needed to raise HF awareness in the public, they did not mention what factors should be focused on raising it. In the present study, factors related to low HF awareness were presented, which were older age, female sex and lower educational level. Increasing HF awareness will require attention and education for those with these risk factors. In particular, our finding showing that HF awareness was lower in elderly women who are more vulnerable to HF may be an important issue not only clinically but also socially in the rapidly aging Korean society.

18) In more specific ways to improve HF awareness in the general population, home visits, education through caregivers, HF campaign and increased opportunities for media contact should be focused especially on elderly women with low educational levels in Korea. Poor health literacy is associated with failure to seek medical help, decreased utilization of health care services and worse clinical outcome.

19)20)21) In our study, people with low HF awareness were older and less educated; hence, they will need easy access to the information and easier and useful education tools such as picture-based explanations could be more helpful. Improved HF awareness may lead to a visit to the hospital when suspected HF, and early treatment of HF may improve the prognosis.

There are several limitations to this study. First, selection bias might exist because only those who could answer all of the survey items were enrolled in the study. Second, although survey items used in our study were originated from published studies and were reviewed by HF specialists, it was not validated. Third, data on some other possible factors affecting HF awareness such as occupations and family members (whether there is a family member or family member with HF) was not collected. Lastly, since our study population was all Korean, our results cannot be applied to other ethnic groups.

In conclusion, older age, female sex, and lower educational level were independently associated with low HF awareness in the general Korean population. More attention and education are needed for these vulnerable groups to improve HF awareness.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download