1. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Collins R, Peto R. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009; 373:1083–1096. PMID:

19299006.

2. Singh GM, Danaei G, Farzadfar F, Stevens GA, Woodward M, Wormser D, Kaptoge S, Whitlock G, Qiao Q, Lewington S, Di Angelantonio E, Vander Hoorn S, Lawes CM, Ali MK, Mozaffarian D, Ezzati M. Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group. Asia-Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration (APCSC). Diabetes Epidemiology: Collaborative analysis of Diagnostic criteria in Europe (DECODE). Emerging Risk Factor Collaboration (ERFC). Prospective Studies Collaboration (PSC). The age-specific quantitative effects of metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: a pooled analysis. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e65174. PMID:

23935815.

3. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017; 390:2627–2642. PMID:

29029897.

4. Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Zeltser LM, Drewnowski A, Ravussin E, Redman LM, Leibel RL. Obesity pathogenesis: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2017; 38:267–296. PMID:

28898979.

5. Waterson MJ, Horvath TL. Neuronal regulation of energy homeostasis: beyond the hypothalamus and feeding. Cell Metab. 2015; 22:962–970. PMID:

26603190.

6. Gautron L, Elmquist JK, Williams KW. Neural control of energy balance: translating circuits to therapies. Cell. 2015; 161:133–145. PMID:

25815991.

7. Spiegelman BM, Flier JS. Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell. 2001; 104:531–543. PMID:

11239410.

8. Cho YM, Fujita Y, Kieffer TJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1: glucose homeostasis and beyond. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014; 76:535–559. PMID:

24245943.

9. Davies MJ, D'Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, Rossing P, Tsapas A, Wexler DJ, Buse JB. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018; 41:2669–2701. PMID:

30291106.

10. Ko SH, Hur KY, Rhee SY, Kim NH, Moon MK, Park SO, Lee BW, Kim HJ, Choi KM, Kim JH. Committee of Clinical Practice Guideline of Korean Diabetes Association. Antihyperglycemic agent therapy for adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus 2017: a position statement of the Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes Metab J. 2017; 41:337–348. PMID:

29086531.

11. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, Greenway F, Halpern A, Krempf M, Lau DC, le Roux CW, Violante Ortiz R, Jensen CB, Wilding JP. SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes NN8022-1839 Study Group. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:11–22. PMID:

26132939.

13. O'Neil PM, Birkenfeld AL, McGowan B, Mosenzon O, Pedersen SD, Wharton S, Carson CG, Jepsen CH, Kabisch M, Wilding JPH. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide compared with liraglutide and placebo for weight loss in patients with obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo and active controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018; 392:637–649. PMID:

30122305.

14. Lockie SH, Heppner KM, Chaudhary N, Chabenne JR, Morgan DA, Veyrat-Durebex C, Ananthakrishnan G, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Drucker DJ, DiMarchi R, Rahmouni K, Oldfield BJ, Tschop MH, Perez-Tilve D. Direct control of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis by central nervous system glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling. Diabetes. 2012; 61:2753–2762. PMID:

22933116.

15. Xu F, Lin B, Zheng X, Chen Z, Cao H, Xu H, Liang H, Weng J. GLP-1 receptor agonist promotes brown remodelling in mouse white adipose tissue through SIRT1. Diabetologia. 2016; 59:1059–1069. PMID:

26924394.

16. Beiroa D, Imbernon M, Gallego R, Senra A, Herranz D, Villarroya F, Serrano M, Ferno J, Salvador J, Escalada J, Dieguez C, Lopez M, Frühbeck G, Nogueiras R. GLP-1 agonism stimulates brown adipose tissue thermogenesis and browning through hypothalamic AMPK. Diabetes. 2014; 63:3346–3358. PMID:

24917578.

17. van Can J, Sloth B, Jensen CB, Flint A, Blaak EE, Saris WH. Effects of the once-daily GLP-1 analog liraglutide on gastric emptying, glycemic parameters, appetite and energy metabolism in obese, non-diabetic adults. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014; 38:784–793. PMID:

23999198.

18. Secher A, Jelsing J, Baquero AF, Hecksher-Sorensen J, Cowley MA, Dalboge LS, Hansen G, Grove KL, Pyke C, Raun K, Schaffer L, Tang-Christensen M, Verma S, Witgen BM, Vrang N, Bjerre Knudsen L. The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide-dependent weight loss. J Clin Invest. 2014; 124:4473–4488. PMID:

25202980.

19. Alhadeff AL, Rupprecht LE, Hayes MR. GLP-1 neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract project directly to the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens to control for food intake. Endocrinology. 2012; 153:647–658. PMID:

22128031.

20. Richard JE, Farkas I, Anesten F, Anderberg RH, Dickson SL, Gribble FM, Reimann F, Jansson JO, Liposits Z, Skibicka KP. GLP-1 receptor stimulation of the lateral parabrachial nucleus reduces food intake: neuroanatomical, electrophysiological, and behavioral evidence. Endocrinology. 2014; 155:4356–4367. PMID:

25116706.

21. Krieger JP, Arnold M, Pettersen KG, Lossel P, Langhans W, Lee SJ. Knockdown of GLP-1 receptors in vagal afferents affects normal food intake and glycemia. Diabetes. 2016; 65:34–43. PMID:

26470787.

22. Jastreboff AM, Lacadie C, Seo D, Kubat J, Van Name MA, Giannini C, Savoye M, Constable RT, Sherwin RS, Caprio S, Sinha R. Leptin is associated with exaggerated brain reward and emotion responses to food images in adolescent obesity. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37:3061–3068. PMID:

25139883.

23. van Bloemendaal L, IJzerman RG, Ten Kulve JS, Barkhof F, Konrad RJ, Drent ML, Veltman DJ, Diamant M. GLP-1 receptor activation modulates appetite- and reward-related brain areas in humans. Diabetes. 2014; 63:4186–4196. PMID:

25071023.

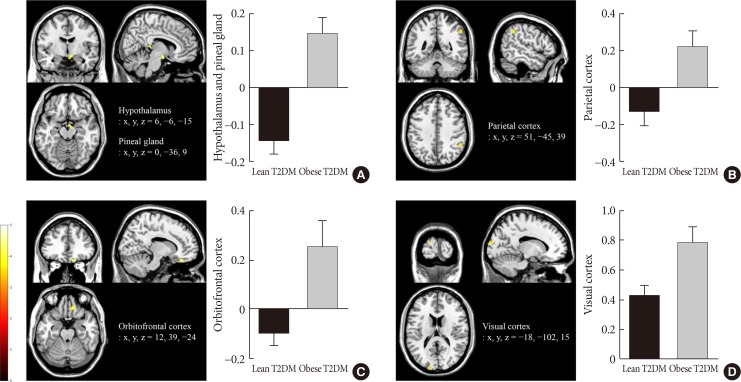

24. Schlogl H, Kabisch S, Horstmann A, Lohmann G, Muller K, Lepsien J, Busse-Voigt F, Kratzsch J, Pleger B, Villringer A, Stumvoll M. Exenatide-induced reduction in energy intake is associated with increase in hypothalamic connectivity. Diabetes Care. 2013; 36:1933–1940. PMID:

23462665.

25. Eldor R, Daniele G, Huerta C, Al-Atrash M, Adams J, DeFronzo R, Duong T, Lancaster J, Zirie M, Jayyousi A, Abdul-Ghani M. Discordance between central (brain) and pancreatic action of exenatide in lean and obese subjects. Diabetes Care. 2016; 39:1804–1810. PMID:

27489336.

26. Farr OM, Sofopoulos M, Tsoukas MA, Dincer F, Thakkar B, Sahin-Efe A, Filippaios A, Bowers J, Srnka A, Gavrieli A, Ko BJ, Liakou C, Kanyuch N, Tseleni-Balafouta S, Mantzoros CS. GLP-1 receptors exist in the parietal cortex, hypothalamus and medulla of human brains and the GLP-1 analogue liraglutide alters brain activity related to highly desirable food cues in individuals with diabetes: a crossover, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2016; 59:954–965. PMID:

26831302.

27. Ten Kulve JS, Veltman DJ, van Bloemendaal L, Barkhof F, Drent ML, Diamant M, IJzerman RG. Liraglutide reduces CNS activation in response to visual food cues only after short-term treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016; 39:214–221. PMID:

26283736.

28. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004; 363:157–163. PMID:

14726171.

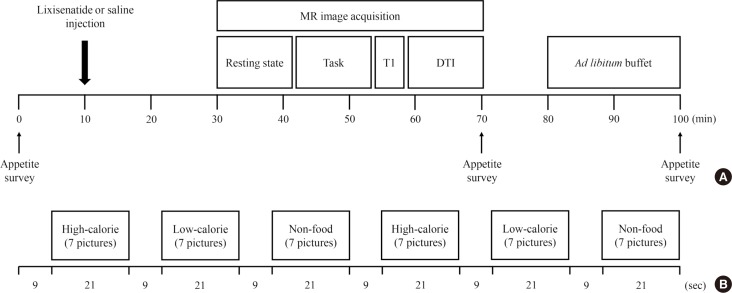

29. Flint A, Raben A, Blundell JE, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000; 24:38–48. PMID:

10702749.

30. Blechert J, Meule A, Busch NA, Ohla K. Food-pics: an image database for experimental research on eating and appetite. Front Psychol. 2014; 5:617. PMID:

25009514.

31. Desmond JE, Glover GH. Estimating sample size in functional MRI (fMRI) neuroimaging studies: statistical power analyses. J Neurosci Methods. 2002; 118:115–128. PMID:

12204303.

32. Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW. Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature. 2006; 443:289–295. PMID:

16988703.

33. Sweeney P, Yang Y. Neural circuit mechanisms underlying emotional regulation of homeostatic feeding. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017; 28:437–448. PMID:

28279562.

34. Stefater MA, Seeley RJ. Central nervous system nutrient signaling: the regulation of energy balance and the future of dietary therapies. Annu Rev Nutr. 2010; 30:219–235. PMID:

20225935.

35. Thaler JP, Guyenet SJ, Dorfman MD, Wisse BE, Schwartz MW. Hypothalamic inflammation: marker or mechanism of obesity pathogenesis. Diabetes. 2013; 62:2629–2634. PMID:

23881189.

36. Grosshans M, Vollmert C, Vollstaedt-Klein S, Nolte I, Schwarz E, Wagner X, Leweke M, Mutschler J, Kiefer F, Bumb JM. The association of pineal gland volume and body mass in obese and normal weight individuals: a pilot study. Psychiatr Danub. 2016; 28:220–224. PMID:

27658830.

37. Gamble KL, Berry R, Frank SJ, Young ME. Circadian clock control of endocrine factors. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014; 10:466–475. PMID:

24863387.

38. Freedman DJ, Ibos G. An integrative framework for sensory, motor, and cognitive functions of the posterior parietal cortex. Neuron. 2018; 97:1219–1234. PMID:

29566792.

39. Murdaugh DL, Cox JE, Cook EW 3rd, Weller RE. fMRI reactivity to high-calorie food pictures predicts short- and long-term outcome in a weight-loss program. Neuroimage. 2012; 59:2709–2721. PMID:

22332246.

40. Grabenhorst F, Rolls ET. Value, pleasure and choice in the ventral prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011; 15:56–67. PMID:

21216655.

41. Levy DJ, Glimcher PW. Comparing apples and oranges: using reward-specific and reward-general subjective value representation in the brain. J Neurosci. 2011; 31:14693–14707. PMID:

21994386.

42. Suzuki S, Cross L, O'Doherty JP. Elucidating the underlying components of food valuation in the human orbitofrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2017; 20:1780–1786. PMID:

29184201.

43. Raun K, von Voss P, Gotfredsen CF, Golozoubova V, Rolin B, Knudsen LB. Liraglutide, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 analog, reduces body weight and food intake in obese candy-fed rats, whereas a dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor, vildagliptin, does not. Diabetes. 2007; 56:8–15. PMID:

17192459.

44. Cornier MA, Salzberg AK, Endly DC, Bessesen DH, Rojas DC, Tregellas JR. The effects of overfeeding on the neuronal response to visual food cues in thin and reduced-obese individuals. PLoS One. 2009; 4:e6310. PMID:

19636426.

45. Castellanos EH, Charboneau E, Dietrich MS, Park S, Bradley BP, Mogg K, Cowan RL. Obese adults have visual attention bias for food cue images: evidence for altered reward system function. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009; 33:1063–1073. PMID:

19621020.

46. Nijs IM, Muris P, Euser AS, Franken IH. Differences in attention to food and food intake between overweight/obese and normal-weight females under conditions of hunger and satiety. Appetite. 2010; 54:243–254. PMID:

19922752.

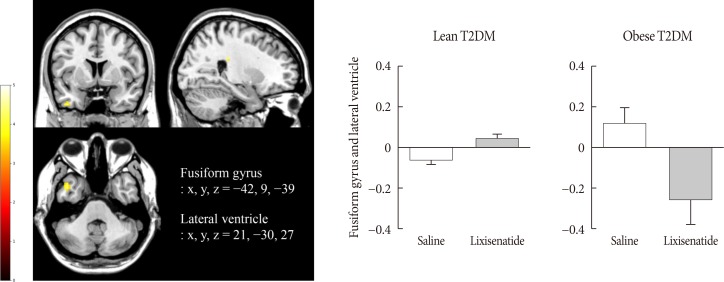

47. Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J Neurosci. 1997; 17:4302–4311. PMID:

9151747.

48. Grill-Spector K, Kourtzi Z, Kanwisher N. The lateral occipital complex and its role in object recognition. Vision Res. 2001; 41:1409–1422. PMID:

11322983.

49. van der Laan LN, de Ridder DT, Viergever MA, Smeets PA. The first taste is always with the eyes: a meta-analysis on the neural correlates of processing visual food cues. Neuroimage. 2011; 55:296–303. PMID:

21111829.

50. DiFeliceantonio AG, Coppin G, Rigoux L, Edwin Thanarajah S, Dagher A, Tittgemeyer M, Small DM. Supra-additive effects of combining fat and carbohydrate on food reward. Cell Metab. 2018; 28:33–44. PMID:

29909968.

51. Richards P, Parker HE, Adriaenssens AE, Hodgson JM, Cork SC, Trapp S, Gribble FM, Reimann F. Identification and characterization of GLP-1 receptor-expressing cells using a new transgenic mouse model. Diabetes. 2014; 63:1224–1233. PMID:

24296712.

52. Cork SC, Richards JE, Holt MK, Gribble FM, Reimann F, Trapp S. Distribution and characterisation of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor expressing cells in the mouse brain. Mol Metab. 2015; 4:718–731. PMID:

26500843.

53. Kroemer NB, Krebs L, Kobiella A, Grimm O, Vollstadt-Klein S, Wolfensteller U, Kling R, Bidlingmaier M, Zimmermann US, Smolka MN. (Still) longing for food: insulin reactivity modulates response to food pictures. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013; 34:2367–2380. PMID:

22461323.

54. Guthoff M, Grichisch Y, Canova C, Tschritter O, Veit R, Hallschmid M, Haring HU, Preissl H, Hennige AM, Fritsche A. Insulin modulates food-related activity in the central nervous system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010; 95:748–755. PMID:

19996309.

55. Kern W, Benedict C, Schultes B, Plohr F, Moser A, Born J, Fehm HL, Hallschmid M. Low cerebrospinal fluid insulin levels in obese humans. Diabetologia. 2006; 49:2790–2792. PMID:

16951936.

56. Johnson KA, Becker JA. The whole brain atlas. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;1999.

57. Silva-Vargas V, Maldonado-Soto AR, Mizrak D, Codega P, Doetsch F. Age-dependent niche signals from the choroid plexus regulate adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2016; 19:643–652. PMID:

27452173.

58. Botfield HF, Uldall MS, Westgate CSJ, Mitchell JL, Hagen SM, Gonzalez AM, Hodson DJ, Jensen RH, Sinclair AJ. A glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist reduces intracranial pressure in a rat model of hydrocephalus. Sci Transl Med. 2017; 9:eaan0972. PMID:

28835515.

59. Zlokovic BV, Jovanovic S, Miao W, Samara S, Verma S, Farrell CL. Differential regulation of leptin transport by the choroid plexus and blood-brain barrier and high affinity transport systems for entry into hypothalamus and across the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. Endocrinology. 2000; 141:1434–1441. PMID:

10746647.

60. Glage S, Klinge PM, Miller MC, Wallrapp C, Geigle P, Hedrich HJ, Brinker T. Therapeutic concentrations of glucagon-like peptide-1 in cerebrospinal fluid following cell-based delivery into the cerebral ventricles of cats. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2011; 8:18. PMID:

21575271.

61. Christensen M, Sparre-Ulrich AH, Hartmann B, Grevstad U, Rosenkilde MM, Holst JJ, Vilsboll T, Knop FK. Transfer of liraglutide from blood to cerebrospinal fluid is minimal in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015; 39:1651–1654. PMID:

26228460.

62. Dietrich MO, Spuch C, Antequera D, Rodal I, de Yebenes JG, Molina JA, Bermejo F, Carro E. Megalin mediates the transport of leptin across the blood-CSF barrier. Neurobiol Aging. 2008; 29:902–912. PMID:

17324488.

63. Imai K, Tsujimoto T, Goto A, Goto M, Kishimoto M, Yamamoto-Honda R, Noto H, Kajio H, Noda M. Prediction of response to GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014; 6:110. PMID:

25349635.

64. Monami M, Dicembrini I, Nreu B, Andreozzi F, Sesti G, Mannucci E. Predictors of response to glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: a meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Diabetol. 2017; 54:1101–1114. PMID:

28932989.

65. Vilsboll T, Christensen M, Junker AE, Knop FK, Gluud LL. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on weight loss: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012; 344:d7771. PMID:

22236411.

66. Meier JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonists for individualized treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012; 8:728–742. PMID:

22945360.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download