“What’s true of all the evils in the world is true of plague as well. It helps men to rise above themselves.”

– Albert Camus, The Plague

About two months have just passed since the first report of patients with pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. The outbreak of infection with the novel coronavirus, now named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has spread to 25 countries since [1]. The global number of cases exceeded 70,000, of which more than 800 occurred outside China. Some suggest that the epidemic is showing signs of slowing down, as the number of new cases in China has been declining in recent days. However, it seems to be too early to relax; during the last two weeks troubling signs have been observed elsewhere in the world – cases without identifiable links are being reported in countries with close proximity and a high volume of traffic with China, including Korea.

Transmission dynamics from the earliest period of the outbreak showed the characteristics which might make containment difficult [23]. A relatively large proportion of mild cases, high viral shedding at the symptom onset, and slowly progressive clinical course undermine the effectiveness of the classic “search and isolate” strategy. Characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) more closely resemble those of influenza A(H1N1) pdm09, which we failed to contain, than those of SARS-CoV in 2003. However, prevention and control strategies are more difficult than those for influenza pandemic, since morbidity is different and no vaccine or specific treatment agents against this new virus are expected in the near future. The recent identification of locally transmitted cases outside China without identifiable links suggests that the containment strategy might have reached its limit. While we have concentrated our effort on the containment of imported cases so far, what we have observed are calls for the preparation for the next stage: sustained transmission in countries outside China.

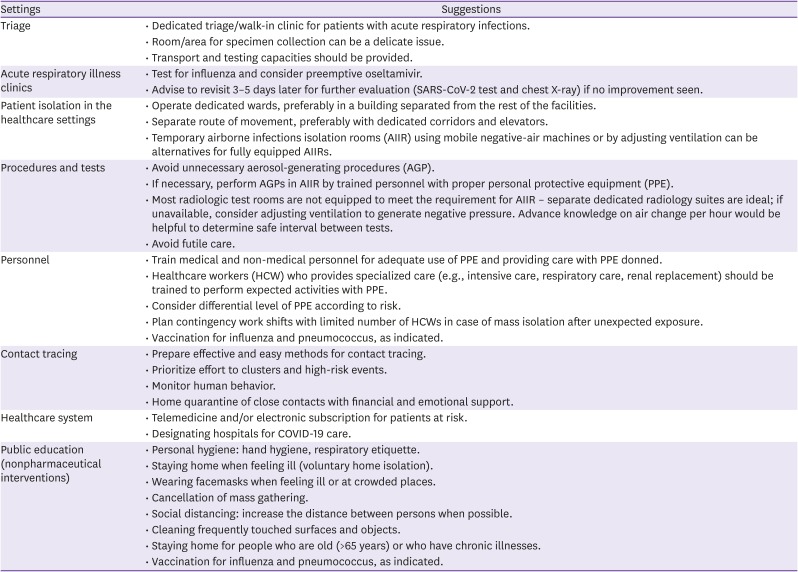

Even if a widespread epidemic does occur, the magnitude and velocity of the epidemic would be the critical factors determining its impact on society. Rapid spread with a high number of cases will saturate the capacity of healthcare system, resulting in excessively high toll of mortality and morbidity; in contrast, slower propagation will allow us time and resources for adequate preparation and management. Thus, efforts for mitigating transmission risk is still important even in the worst situation. Weak spots in systems and societies should be identified. History of recent epidemics – SARS, Ebola, and MERS – universally taught us that healthcare facilities, which comprise the pillars of our healthcare, are at particular risk at the time of epidemic. Hospitals have become stages of super-spreading events during SARS and MERS outbreaks [45]. Outpatients and emergency departments, which serve as gatekeepers of hospitals, are expected to be most exposed. Facilities should formulate detailed plans for safe and effective screening, isolation, and testing of suspected cases (Table 1); otherwise, an increased number of patients and confusion on the front line may make those places epicenter of hospital-associated outbreaks. A dedicated triage area, perhaps makeshift, can serve as a safety barrier for a healthcare facility. Triage could utilize a clinical pathway to manage patients with symptoms of acute respiratory illness: for example, test and treat for influenza or other bacterial causes first with voluntary home isolation, then test for COVID-19 if unresponsive 3 - 5 days later [6]. Use of telemedicine or electronic prescription can be considered to reduce the need for outpatient visits. Hospitals should also build contingency plans for general wards and intensive care units. Care for numerous patients with COVID-19 would require a large number of airborne infections isolation rooms (AIIR) which greatly exceed the current capacity. Building temporary AIIRs with mobile negative-air machines or by adjusting ventilation systems can be useful alternatives, as demonstrated in Korea during the MERS outbreak. Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC), along with sewage and waste handling, should be reviewed when general-purpose wards need be used for management of COVID-19 patients. Private practices and pharmacies face unique challenges, due to lack of capacity for isolation and testing. Effective workflow for screening and referral of patients are necessary, and public health authorities should work with the community to provide adequate support to this foundation of our healthcare.

Early diagnosis and isolation of cases will slow the transmission, mitigate the risk of outbreaks, and improve clinical outcomes. Most recent cases diagnosed in Singapore, Japan, and Korea demonstrate that the case definition based on travel history or contact with confirmed cases became insufficient. More systematic surveillance among acute respiratory illness is now required. United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention recently announced that it will consider adding SARS-CoV-2 to its existing influenza-like illness surveillance [7]. We believe that other countries should also prepare for implementing similar measures, and they could benefit from global coordination. Healthcare facilities need to conceive effective pathways to screen, test, and isolate patients with acute respiratory infections in various care settings. Surge capacity of laboratories is also of important concern and the development of rapid, point-of-care test will greatly relieve the laboratory burden and contribute to rapid diagnosis.

Sustained transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the community will result in a surge of patients, both with and without COVID-19. Efforts should be made to provide adequate care for both groups of patients. Multiple media reports from Wuhan and Hubei province tell the story of sick people unable to access medical care. Overflow of healthcare system will unequivocally lead to suboptimal outcome in all patients regardless of their diagnosis. Surge capacities should be prepared, in terms of infrastructures, human and material resources, procedures, and organizations. Healthcare facilities should secure extra beds and instruments (e.g., ventilators) for surge capacity. Patients who could be cared at home or at long-term care facilities should be discharged, and elective medical care could be postponed. Resources for care of patients with COVID-19 needs to be checked and stocked. While their effects are yet to be proven by clinical trials, agents such as lopinavir/ritonavir, interferon, chloroquine, and remdesivir have been used for treatment [89]. Antibiotics are expected to be administered to many patients, thus their stocks and contingency supply plan must be reviewed. Medical surge operation cannot be executed effectively by individual facilities alone. Public health authorities should coordinate joint operations to utilize limited resources in the most effective way. Designating hospitals for COVID-19 care would be more beneficial for the efficient use of limited resources and could maintain essential healthcare for patients requiring emergent or intensive management for other diseases.

Control of a large epidemic will require individual cooperation from the public [10]. Common sense etiquettes will help mitigate the risk of transmission: hand hygiene, cough etiquette, and avoiding crowded places for high-risk people (e.g., elderly or immunocompromised). People with mild symptoms of acute respiratory illness are not likely to benefit from medical care, regardless of etiologic agents. Visiting healthcare facilities without proper protection will risk others if one has COVID-19, or risk oneself otherwise. The public should be advised to stay home if mildly ill, and seek medical care in a coordinated way if symptoms persist or aggravate. There still remains approximately a month until the flu season is expected to end and Streptococcus pneumoniae causes bacterial pneumonia year wise. Vaccination for influenza and pneumococcus, particularly for the high-risk population, should be recommended. Decrease in those conditions will reduce the burden on healthcare system and also lower the risk of contracting COVID-19 in healthcare settings. Healthcare authorities should prepare a sufficient amount of influenza vaccines for the next season.

Places of mass congregation, such as supermarkets, hotels, conferences, religious services, and schools, deserve special interest. They can serve as focal points of small outbreaks; even when they don't, patients visiting public places before isolation leads to massive contact tracing, which consumes precious resources and elicits public anxiety. Temporary closure of schools and non-critical services could be considered. At places staying open, observation of personal hygiene is likely to be helpful for lowering transmission risk.

As physicians working in the field of infectious diseases, it is heartbreaking to hear reports on the current situation in Wuhan. Much of the sufferings of people in the city are for the good of us outside, rather than for their own good. We are greatly indebted to their sacrifice; it has earned us valuable time to prepare for the next stage. We, as medical professionals and as a society, should not spend in vain the time earned with so much suffering.

Special thanks to the people in Wuhan and the great effort of China.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Express sincere gratitude to Dr. Yea-Jean Kim for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), Situation Report – 29. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO;2020. 2. 18.

2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020; 395:497–506. PMID: 31986264.

3. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, Yu J, Kang M, Song Y, Xia J, Guo Q, Song T, He J, Yen HL, Peiris M, Wu J. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

4. McDonald LC, Simor AE, Su IJ, Maloney S, Ofner M, Chen KT, Lando JF, McGeer A, Lee ML, Jernigan DB. SARS in healthcare facilities, Toronto and Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004; 10:777–781. PMID: 15200808.

5. Cho SY, Kang JM, Ha YE, Park GE, Lee JY, Ko JH, Lee JY, Kim JM, Kang CI, Jo IJ, Ryu JG, Choi JR, Kim S, Huh HJ, Ki CS, Kang ES, Peck KR, Dhong HJ, Song JH, Chung DR, Kim YJ. MERS-CoV outbreak following a single patient exposure in an emergency room in South Korea: an epidemiological outbreak study. Lancet. 2016; 388:994–1001. PMID: 27402381.

6. Zhang J, Zhou L, Yang Y, Peng W, Wang W, Chen X. Therapeutic and triage strategies for 2019 novel coronavirus disease in fever clinics. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

7. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Transcript for CDC media telebriefing: update on COVID-19. Accessed February 20 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/t0214-covid-19-update.html.html.

8. Mo Y, Fisher D. A review of treatment modalities for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016; 71:3340–3350. PMID: 27585965.

9. Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, Spitters C, Ericson K, Wilkerson S, Tural A, Diaz G, Cohn A, Fox L, Patel A, Gerber SI, Kim L, Tong S, Lu X, Lindstrom S, Pallansch MA, Weldon WC, Biggs HM, Uyeki TM, Pillai SK. Washington State 2019-nCoV Case Investigation Team. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

Table 1

Practical suggestions for contingency plans

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download