Abstract

Background

Autologous stem cell transplantation (autoSCT) can extend remission of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), but the management of subsequent relapse is challenging.

Methods

We examined consecutive patients with MCL who underwent autoSCT at Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System between 2009 and 2017 (N=37).

Results

Ten patients experienced disease progression after autoSCT and were included in this analysis. Median progression free survival after autoSCT was 1.8 years (range, 0.3–7.1) and median overall survival after progression was only 0.7 years (range, 0.1 to not reached). The 3 patients who survived more than 1 year after progression were treated with ibrutinib.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma that follows a variable but typically aggressive course. For those younger than 65 years old and fit with advanced stage disease requiring treatment, an intensive, multi-phase treatment regimen is standard. This commonly includes induction using cytarabine-containing chemo-immunotherapy and, for those in remission, consolidation with high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (autoSCT) followed by up to three years of maintenance rituximab [1234]. With this approach, median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) exceeds 5 and 10 years, respectively.

Nevertheless, progression after autoSCT in MCL regularly occurs and management of such cases can be a challenge within the context of extensive prior therapy. While evidence supporting each phase of the initial therapies is established, studies that inform prognosis and management of post-autoSCT relapse of MCL are relatively few [5678]. Several biologically targeted agents have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for relapsed or refractory MCL, including the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, two Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors (ibrutinib and acalabrutinib), and the immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide. Venetoclax, an inhibitor of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2, has shown promising activity as well and is listed for consideration of use in relapsed MCL by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, though to date it has not been FDA-approved for this indication [9]. Cytotoxic chemotherapies with or without rituximab are also routinely used in relapsed MCL, especially in cases where extended remissions were achieved with related regimens. Combinations of targeted and cytotoxic agents are also emerging as attractive options. Navigating among these choices and providing patients an evidence-based prognosis for MCL progressing after autoSCT has become increasingly complex.

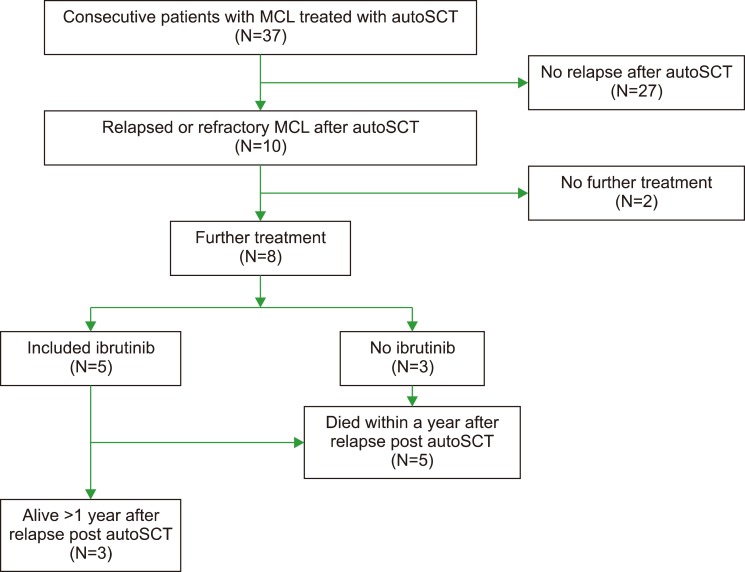

We performed a retrospective analysis of patients with MCL that underwent autoSCT at Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) between 2009 and 2017. Consecutive patients (N=37) with a histopathologic diagnosis of MCL and treated with autoSCT were evaluated and those with progression of disease after transplant (N=10) were included (Fig. 1). Records were examined for physician documentation of symptoms and physical exam, as well as standard laboratory tests and relevant imaging to determine disease stage and response to therapy per standard criteria [10]. After autoSCT, follow-up and treatment decisions were performed according to each patient's local managing oncologist. PFS and OS after autoSCT, starting with the date of transplant, were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System.

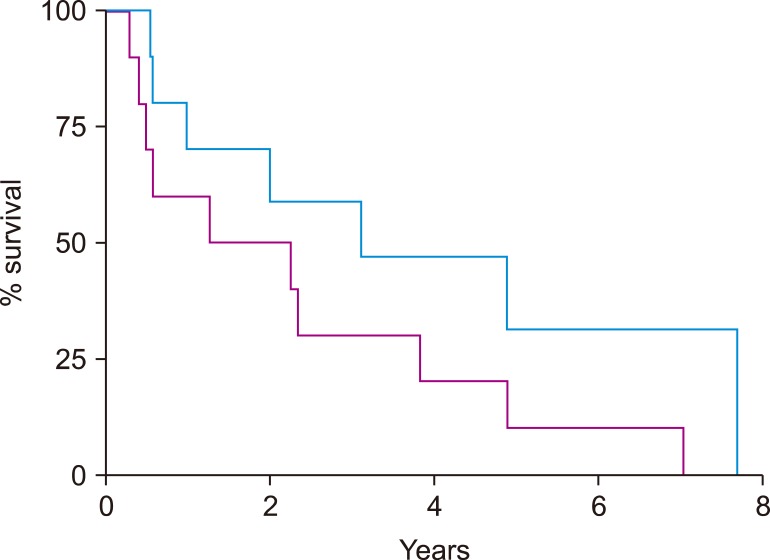

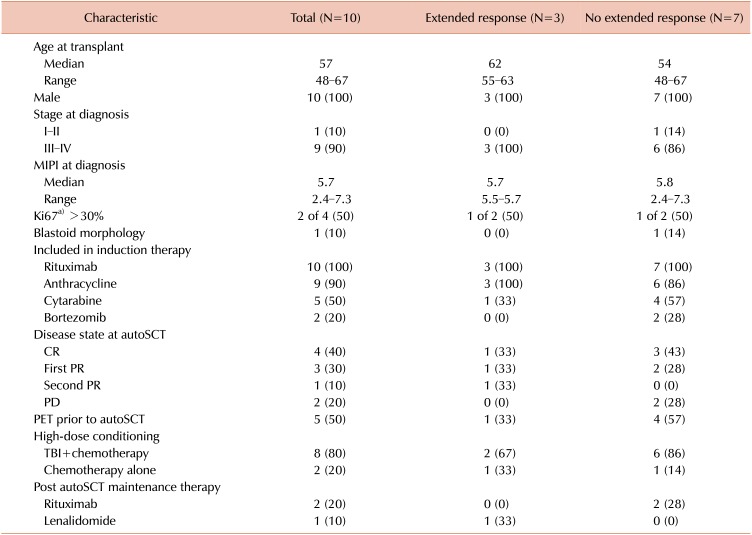

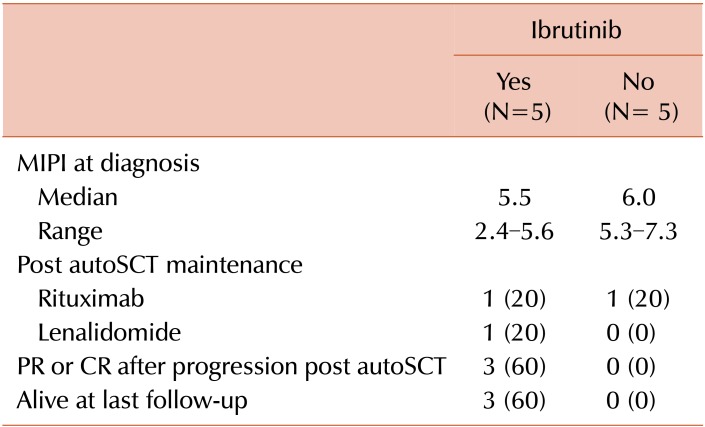

Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. All patients were male, reflective of the VA population and the increased incidence of MCL in males. The median mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index (MIPI) at diagnosis was 5.7 (range, 2.4–7.3). At transplant, median age was 57 years (range, 48–67) and MCL was in first complete remission (CR) in 4 patients, first partial remission (PR) in 3 patients, and second PR in 1 patient. Two patients had progressive disease (PD) at autoSCT. High-dose conditioning therapy consisted of a total body irradiation (TBI) based regimen in 8 patients and 2 patients received chemotherapy only, consisting of carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM). Median follow-up after autoSCT was 2.6 years (range, 0.5–7.7). Three patients received post-autoSCT maintenance therapy (rituximab in 2, lenalidomide in 1). After autoSCT the median PFS was 1.8 years (range, 0.3–7.1) and the median OS was 3.1 years (range, 0.5 to not reached) (Fig. 2). Progression was observed both early, within 6 months of transplant (N=3), and late, >3 years after transplant (N=3).

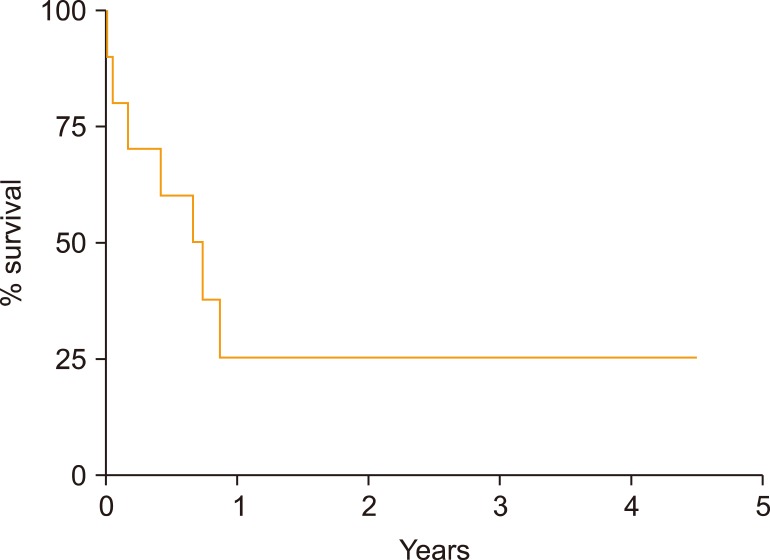

In these 10 patients with relapsed MCL after autoSCT, median survival after relapse was 0.7 years (range, 0.1 to not reached) (Fig. 3). Seven of 10 patients died within 1 year, with 3 remaining alive at the time of this analysis. Eight received at least one line of additional therapy: 2 received rituximab with cytotoxic chemotherapy [bendamustine (BR) in 1 and ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (RICE) in 1]; 1 received bortezomib plus rituximab, and 5 received therapy that included ibrutinib (ibrutinib monotherapy in 3, ibrutinib with BR in 1, and ibrutinib with rituximab in 1). Three patients received further lines of therapy, including BR after failure of ibrutinib with rituximab, an allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) with nonmyeloablative conditioning after RICE, and venetoclax followed by chimeric- antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy after failure of ibrutinib with BR.

The 3 patients alive more than 1 year post-autoSCT relapse were treated initially with ibrutinib monotherapy at progression. All were documented to have at least a PR with ibrutinib, with a median duration of remission of 14.8 months (range, 5.7–50.4); none required additional therapies. They had similar baseline characteristics to the cohort as a whole (Table 1) and relapsed at various times after autoSCT (0.3, 2.3, and 3.8 yr). Ibrutinib was well tolerated at standard dose in each of these cases without major toxicity or need for dose adjustment. No objective remissions were seen in the patients that received ibrutinib-combination regimens, cytotoxic chemotherapy, or bortezomib-based therapy in the post-autoSCT relapse setting (Table 2).

In our cohort we found that relapse of MCL after autoSCT is associated with an extremely poor prognosis. Nonetheless, there is a subset of patients that achieve significant benefit from additional therapy. While our cohort size is relatively small, the findings align with previously published retrospective data from other groups. Dietrich et al. [5] performed a large registry database study and reported a median OS of patients with MCL relapsing after autoSCT of 19 months. In their cohort, which pre-dated availability of ibrutinib, 82% of patients receiving treatment for post-autoSCT disease progression were initially administered a cytotoxic chemotherapy-based regimen and 22% of patients ultimately proceeded to alloSCT, which can be effective in refractory MCL [6]. An additional observation was that patients treated with cytarabine based induction had significantly worse outcomes, possibly reflecting a selection for more aggressive disease biology at relapse. Visco et al. [8] recently published an analysis showing relapse or progression of MCL within 2 years following intensive induction chemoimmunotherapy to be a powerful factor associated with worse survival. Twenty-two percent of the patients in their cohort also went on to undergo alloSCT; otherwise, limited data on treatments post-autoSCT relapse were included.

Employing targeted rather than conventional cytotoxic agents in the setting of disease progression post autoSCT is attractive both for the potential efficacy of harnessing an untapped therapeutic mechanism and for the relatively acceptable tolerability. In support of this hypothesis, Rule et al. [11] pooled data from 3 studies of ibrutinib in relapsed/refractory MCL (N=370), which included patients who underwent prior autoSCT, and found an objective response rate of 66% with a median PFS and OS of 12.8 and 25.0 months, respectively. That all patients in our series with extended survival after relapse following autoSCT were treated initially with ibrutinib further suggests that use of a biologically targeted approach may be preferable in cases of MCL relapsed after chemo- and radiation- based therapy.

This study is limited by its modest size and retrospective nature; additionally, since patients returned to their primary oncologist after transplantation some details of their follow- up, such as MIPI score and disease bulk at the time of their post-autoSCT treatment, are not uniformly accessible. It is possible that selection of ibrutinib monotherapy was made in the context of less-aggressive features of relapse. Also Ki67, an important prognostic marker for MCL, was performed at diagnosis in a minority of this cohort (Table 1) [12]. Newer biomarkers such as aberrations in TP53 and disease-specific gene proliferation signatures, which are emerging as useful MIPI-independent prognostic markers and predictors of lack of response to standard therapy, were not examined [1314].

Future research is required to better define the best treatment for patients with MCL relapsed after autoSCT. Rationally combining targeted and cytotoxic therapies promises additional progress, though where these options fit alongside therapies including salvage alloSCT and, potentially, CAR-T therapy remains to be defined [151617]. For now, individualization of treatment recommendations after review of available treatments, toxicities, and clinical trial options will continue to guide management in this challenging situation.

References

1. Gerson JN, Handorf E, Villa D, et al. Survival outcomes of younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2019; 37:471–480. PMID: 30615550.

2. Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al. Rituximab after autologous stem-cell transplantation in mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:1250–1260. PMID: 28953447.

3. Hermine O, Hoster E, Walewski J, et al. Addition of high-dose cytarabine to immunochemotherapy before autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients aged 65 years or younger with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL Younger): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. Lancet. 2016; 388:565–575. PMID: 27313086.

4. Graf SA, Stevenson PA, Holmberg LA, et al. Maintenance rituximab after autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2015; 26:2323–2328. PMID: 26347113.

5. Dietrich S, Boumendil A, Finel H, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma relapsing after autologous stem-cell transplantation: a retrospective study of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Ann Oncol. 2014; 25:1053–1058. PMID: 24585719.

6. Vaughn JE, Sorror ML, Storer BE, et al. Long-term sustained disease control in patients with mantle cell lymphoma with or without active disease after treatment with allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Cancer. 2015; 121:3709–3716. PMID: 26207349.

7. Stefoni V, Pellegrini C, Broccoli A, et al. Lenalidomide in pretreated mantle cell lymphoma patients: an Italian observational multicenter retrospective study in daily clinical practice (the Lenamant Study). Oncologist. 2018; 23:1033–1038. PMID: 29674440.

8. Visco C, Tisi MC, Evangelista A, et al. Time to progression of mantle cell lymphoma after high-dose cytarabine-based regimens defines patients risk for death. Br J Haematol. 2019; 185:940–944. PMID: 30407625.

9. Davids MS, Roberts AW, Seymour JF, et al. Phase I first-in-human study of venetoclax in patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35:826–833. PMID: 28095146.

10. Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014; 32:3059–3068. PMID: 25113753.

11. Rule S, Dreyling M, Goy A, et al. Outcomes in 370 patients with mantle cell lymphoma treated with ibrutinib: a pooled analysis from three open-label studies. Br J Haematol. 2017; 179:430–438. PMID: 28832957.

12. Hoster E, Rosenwald A, Berger F, et al. Prognostic value of Ki-67 index, cytology, and growth pattern in mantle-cell lymphoma: results from randomized trials of the european mantle cell lymphoma network. J Clin Oncol. 2016; 34:1386–1394. PMID: 26926679.

13. Eskelund CW, Dahl C, Hansen JW, et al. TP53 mutations identify younger mantle cell lymphoma patients who do not benefit from intensive chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2017; 130:1903–1910. PMID: 28819011.

14. Scott DW, Abrisqueta P, Wright GW, et al. New molecular assay for the proliferation signature in mantle cell lymphoma applicable to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies. J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35:1668–1677. PMID: 28291392.

15. Tam CS, Anderson MA, Pott C, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for the treatment of mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:1211–1223. PMID: 29590547.

16. Lin RJ, Ho C, Hilden PD, et al. Allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation impacts on outcomes of mantle cell lymphoma with TP53 alterations. Br J Haematol. 2019; 184:1006–1010. PMID: 30537212.

17. Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies for lymphoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018; 15:31–46. PMID: 28857075.

Fig. 1

Diagram of treatments and outcomes after progression of mantle cell lymphoma post autologous stem cell transplantation.

Fig. 2

Progression-free survival (purple) and overall survival (blue) after autologous stem cell transplantation of patients that experienced progression of mantle cell lymphoma after transplant.

Fig. 3

Overall survival after progression following autologous stem cell transplantation of cohort of patients that experienced progression of mantle cell lymphoma after transplant.

Table 1

Patient characteristics, including the whole cohort and according to duration of response to therapy after disease progression post autologous stem cell transplantation.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download