Abstract

Background

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a known cause of morbidity and mortality after bariatric surgery. However, the data concerning appropriate thromboprophylaxis after bariatric surgery is uncertain. The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of extended duration thromboprophylaxis in post-bariatric surgery patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of consecutive patients who underwent bariatric surgery from November 2014 to October 2018 at King Fahad General Hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. All included patients were treated with extended duration thromboprophylaxis.

Results

We identified 374 patients who underwent bariatric surgery during the study period. Of these, 312 patients (83%) were followed for at least 3 months. The most common type of surgery was a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (N=357) and the median weight was 110 kg. The cumulative incidence of symptomatic postoperative VTE at 3 months was 0.64% (95% confidence interval, 0.20–1.52). All events occurred after hospital discharge. The most commonly used pharmacological prophylaxis (91%) for VTE prevention after bariatric surgery was enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously twice daily for 10–14 days after hospital discharge. There were no reported cases of bleeding or VTE related mortality after 3 months.

Go to :

Obesity is a global nutritional problem, putting a high burden on health care resources [1]. The incidence of obesity has been increasing dramatically in the last 3 decades, affecting more than one third of the general population in Saudi Arabia [2]. Bariatric surgeries, which include gastric sleeve, bypass, and banding, are widely used procedures to reduce weight and the incidence of related co-morbidities in obese patients [3]. Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a known cause of morbidity and mortality after bariatric surgery [4]. Obesity is an independent risk factor for VTE; a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 has been shown to increase the VTE risk 2-fold [5]. The reported postoperative incidence of VTE after bariatric surgery, however, varies widely, from 0.2 to 5% [16]. Similarly, the rate of bleeding after surgery varies from 0% to 6% [7]. This variation is likely due to differences in patient characteristics, the type of bariatric surgery, dose of thromboprophylaxis (weight adjusted vs. fixed dose), duration of thromboprophylaxis, and outcomes measured (symptomatic vs. asymptomatic VTE). Fatal PE is a frequent cause of postoperative mortality in the bariatric surgery population [89]. An autopsy study of 10 patients who died after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass concluded that PE was the cause of death for 3 patients [10]. Reported risk factors for VTE after bariatric surgery include: aged over 50 years, postoperative anastomotic leak, history of smoking, and a prior VTE [11].

Although the rate of VTE after bariatric surgery is modest, the increasing prevalence of obesity and bariatric surgeries could lead to a considerable number of VTE complications. VTE is a preventable disease, and thromboprophylaxis is a key strategy for reducing VTE-related mortality and morbidity after bariatric surgery.

There is no consensus regarding the optimal dose or duration of thromboprophylaxis. Despite an agreement that VTE prevention is necessary after bariatric surgery, data concerning the optimal thromboprophylaxis regimen is lacking. Since the majority of VTE complications occur after hospital discharge, an extended thromboprophylaxis approach is necessary, especially for high risk patients [12]. The Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative study, which was conducted to compare different types of thromboprophylaxis, showed that low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) was superior to unfractionated heparin (UFH) for thromboprophylaxis after bariatric surgery with a similar risk of bleeding [13]. Scholten et al. [14] reported greater efficacy with enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily compared to 30 mg twice daily in preventing VTE complications with similar bleeding risk among patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

We believe that an extended thromboprophylaxis regimen is an effective strategy for preventing VTE complications after bariatric surgery. We retrospectively assessed the risk of VTE, bleeding, and mortality among patients undergoing bariatric surgery who received extended fixed dose thromboprophylaxis.

Go to :

We conducted a retrospective study of patients who underwent bariatric surgery at King Fahad General Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia from November 2014 to October 2018. We included adult patients (≥18 yr), with BMIs ≥30 kg/m2 who underwent a sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, or gastric banding. Patients on a full dose of anticoagulation treatment were excluded.

A standardized protocol of 10–14 days of extended thromboprophylaxis was implemented at our institution. The following data on identified patients were collected by reviewing the electronic medical record: demographics, weight, BMI, comorbidities, surgery modality, VTE-related complications, mortality, and bleeding. The dose and duration of thromboprophylaxis including pharmacological and mechanical prophylaxis were recorded. Follow-up data were extracted from the day of admission to the last encounter or death.

The primary outcome of the study was the incidence of symptomatic VTE, including PE, DVT, and splanchnic vein thrombosis within 3 months of bariatric surgery in patients who received thromboprophylaxis. A VTE was recorded after objective identification using a computed tomography pulmonary angiography or a ventilation-perfusion lung scan for PE; a Doppler ultrasonography for DVT; or a CT scan or Duplex ultrasound for splanchnic vein thrombosis. Bleeding was defined according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis [15]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with local research ethics.

We used JASP software (University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), version 0.11.1 to carry out the statistical analysis. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and proportions, and as median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables.

Go to :

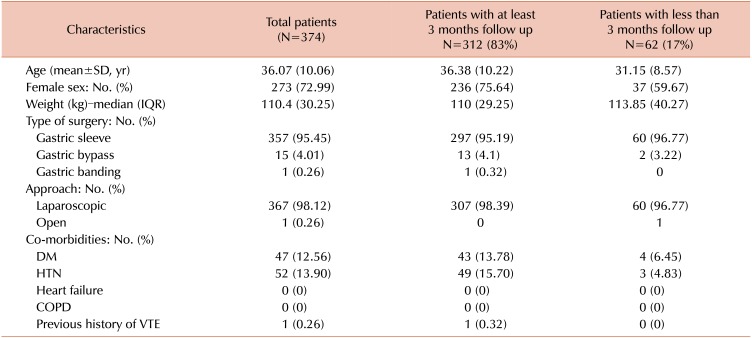

In total, 374 patients underwent bariatric surgery between November 2014 and October 2018. Of these, 312 patients (83%) completed at least 3 months of follow up, while 62 (17%) completed their follow up at another hospital or were followed for less than 3 months.

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age of all patients was 36 years (standard deviation±10 yr) and most them were under 50 years of age. There were more females (273; 73%) than males (101; 27%). The majority of patients (357; 95%) underwent sleeve gastrectomy, while 15 patients (4%) had a gastric bypass, and 1 underwent gastric banding. The median body weight was 110 kg (IQR, 84–180). The BMIs of 239 patients (64%) were between 40 and 59 and were ≥60 in 11 patients (3%). The median follow up time was 4 months (IQR, 0–10).

All patients received thromboprophylaxis after surgery. The majority of patients (91%) were prescribed enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously twice daily for 10–14 days. However, enoxaparin 40 mg once daily was prescribed in 8% of patients and 3 patients were prescribed UFH 5000 units twice daily for 10–14 days due to elevated serum creatinine. All the patients were mobilized on post-operation day 1. Mechanical thromboprophylaxis using graduated compression stocking (GCS) or intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) were not used on our patients. Additionally, antiplatelet medications were not administered to any patient after surgery.

The cumulative incidence of symptomatic postoperative VTE at 3 months was 2/312 patients, or 0.64% (95% confidence interval, 0.20–1.52). Both VTE cases were diagnosed after hospital discharge. Details regarding the patients who developed VTE are shown in Table 2. At the 3-month follow up, there was no reported bleeding or VTE-related mortality.

Go to :

In this study of patients undergoing bariatric surgery, we have demonstrated that extended duration thromboprophylaxis is effective and safe in preventing VTE after bariatric surgery. Nearly all patients in this cohort were managed with a fixed dose of enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily for 10–14 days. The bleeding and mortality rate were 0% at the 3-month follow up.

Our results are consistent with other studies suggesting that an extended duration of thromboprophylaxis may be more effective and safer than in-hospital thromboprophylaxis. In one prospective study, the rate of postoperative VTE and bleeding was 0% for 735 patients who underwent bariatric surgery and received extended duration (1–3 wk) thromboprophylaxis with LMWH [16]. Similarly, Tseng et al. [6], in a retrospective study of 817 patients, reported a 0.5% rate of postoperative VTE in those managed with extended duration (10 days) of tinzaparin.

Early mobilization is essential for this population; therefore, the patients in our study were mobilized on post-operative day 1. Mechanical prophylaxis including GCS and IPC were not used in our patients due to the difficulty in applying these devices in morbidly obese patients. In addition, only limited data based on retrospective studies have compared mechanical prophylaxis to pharmacological prophylaxis [1718]. However, patients with a high risk of bleeding may benefit from mechanical prophylaxis.

Many proposed regimens of thromboprophylaxis have been used postoperatively in bariatric surgery patients, however, the optimal dose and duration is uncertain. Agarwal et al. [19] concluded in a systematic review that UFH 5000 units three times daily or enoxaparin 30–40 mg twice daily are acceptable choices for extended thromboprophylaxis. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies assessing the efficacy and safety of thromboprophylaxis after bariatric surgery, the authors concluded that a fixed thromboprophylaxis dose was as effective as a weight adjusted dose with lower bleeding complications [20]. In contrast, Ikesaka et al. [7] conducted a meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy and safety of weight adjusted thromboprophylaxis (defined as more than enoxaparin 30 mg twice daily or UFH 5000 units three times daily or equivalent) compared to lower, fixed dose thromboprophylaxis after bariatric surgery. They included 6 studies and the rate of VTE was lower in the weight adjusted thromboprophylaxis group (0.5% vs. 2%) without an increased risk of major bleeding [7].

The lack of high-quality randomized trials to assess the appropriate dose and duration of thromboprophylaxis after bariatric surgery has generated a wide variation in published guidelines. In addition, the heterogeneity of available data regarding the type of bariatric surgery, the outcomes measured, type and dose of pharmacological prophylaxis, and duration of extended prophylaxis have added more complexity to determining the most effective and safest thromboprophylaxis regimen for this population. Therefore, The American College of Chest Physicians has not reported specific recommendations for this population [21]. However, the VTE risk after bariatric surgery is considered moderate based on the risk scores used (Caprini or Rogers). Therefore, thromboprophylaxis was recommended but with no specific guidelines for the dose or duration. The European Society of Anesthesiology has recommended extended duration thromboprophylaxis for 10–15 days with LMWH 4000 to 6000 IU every 12 hours for high risk patients [22]. They define high risk VTE patients as those aged >55 years, with a BMI >55 kg/m2, and a history of VTE, venous disease, sleep apnea, hypercoagulability, or pulmonary hypertension. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has suggested extended duration thromboprophylaxis, but due to insufficient data they have not specified a dose or duration [23].

The rate of VTE after bariatric surgery is modest but with the global increase of obesity and associated need for bariatric surgery as an effective approach to reduce weight and the incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity, VTE remains an important preventable complication in this population. Additional large, high quality, randomized, and prospective studies are needed to address unanswered questions regarding VTE prevention in bariatric surgery.

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature and its inclusion of patients only from a single center. Additionally, 3 months of follow up was not available for the 62 patients (17%) who followed up at another hospital after surgery. Furthermore, the sample size and total number of VTE events were relatively small, which prevented us from performing an analysis to identify risk factors for VTE after bariatric surgery.

In summary, VTE is a preventable complication that poses a risk of morbidity and mortality after surgery. However, extended duration thromboprophylaxis appears to be effective after bariatric surgery without increasing the bleeding risk. Additional prospective trials are needed to evaluate the best regimen for VTE prevention after bariatric surgery.

Go to :

Notes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Go to :

References

1. Lau DC, Douketis JD, Morrison KM, et al. 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. CMAJ. 2007; 176:S1–13.

2. Memish ZA, El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, et al. Obesity and associated factors--Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014; 11:E174. PMID: 25299980.

3. Colquitt JL, Picot J, Loveman E, Clegg AJ. Surgery for obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; CD003641. PMID: 19370590.

4. Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008; 133(6 Suppl):381S–453S. PMID: 18574271.

5. Allman-Farinelli MA. Obesity and venous thrombosis: a review. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011; 37:903–907. PMID: 22198855.

6. Tseng EK, Kolesar E, Handa P, et al. Weight-adjusted tinzaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after bariatric surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2018; 16:2008–2015. PMID: 30099852.

7. Ikesaka R, Delluc A, Le Gal G, Carrier M. Efficacy and safety of weight-adjusted heparin prophylaxis for the prevention of acute venous thromboembolism among obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2014; 133:682–687. PMID: 24508449.

8. Sapala JA, Wood MH, Schuhknecht MP, Sapala MA. Fatal pulmonary embolism after bariatric operations for morbid obesity: a 24-year retrospective analysis. Obes Surg. 2003; 13:819–825. PMID: 14738663.

9. Morino M, Toppino M, Forestieri P, Angrisani L, Allaix ME, Scopinaro N. Mortality after bariatric surgery: analysis of 13,871 morbidly obese patients from a national registry. Ann Surg. 2007; 246:1002–1007. PMID: 18043102.

10. Melinek J, Livingston E, Cortina G, Fishbein MC. Autopsy findings following gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002; 126:1091–1095. PMID: 12204059.

11. Gonzalez R, Haines K, Nelson LG, Gallagher SF, Murr MM. Predictive factors of thromboembolic events in patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006; 2:30–35. PMID: 16925311.

12. Oger E. Incidence of venous thromboembolism: a community-based study in Western France. EPI-GETBP Study Group. Groupe d'Etude de la Thrombose de Bretagne Occidentale. Thromb Haemost. 2000; 83:657–660. PMID: 10823257.

13. Birkmeyer NJ, Finks JF, Carlin AM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism following bariatric surgery. Arch Surg. 2012; 147:994–998. PMID: 23165612.

14. Scholten DJ, Hoedema RM, Scholten SE. A comparison of two different prophylactic dose regimens of low molecular weight heparin in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2002; 12:19–24. PMID: 11868291.

15. Schulman S, Angerås U, Bergqvist D, Eriksson B, Lassen MB, Fisher W. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2010; 8:202–204. PMID: 19878532.

16. Magee CJ, Barry J, Javed S, Macadam R, Kerrigan D. Extended thromboprophylaxis reduces incidence of postoperative venous thromboembolism in laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010; 6:322–325. PMID: 20510295.

17. Clements RH, Yellumahanthi K, Ballem N, Wesley M, Bland KI. Pharmacologic prophylaxis against venous thromboembolic complications is not mandatory for all laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2009; 208:917–921. discussion 921-3. PMID: 19476861.

18. Frantzides CT, Welle SN, Ruff TM, Frantzides AT. Routine anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism prevention following laparoscopic gastric bypass. JSLS. 2012; 16:33–37. PMID: 22906327.

19. Agarwal R, Hecht TE, Lazo MC, Umscheid CA. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for patients undergoing bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010; 6:213–220. PMID: 20176509.

20. Becattini C, Agnelli G, Manina G, Noya G, Rondelli F. Venous thromboembolism after laparoscopic bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: clinical burden and prevention. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012; 8:108–115. PMID: 22014482.

21. Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012; 141(2 Suppl):e227S–e277S. PMID: 22315263.

22. Afshari A, Ageno W, Ahmed A, et al. European Guidelines on perioperative venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: Executive summary. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018; 35:77–83. PMID: 29112553.

23. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Clinical Issues Committee. ASMBS updated position statement on prophylactic measures to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism in bariatric surgery patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013; 9:493–497. PMID: 23769113.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download