Abstract

Background

DNMT3A mutations occur in approximately 20% of AML cases and are associated with changes in DNA methylation. CDKN2B plays an important role in the regulation of hematopoietic progenitor cells and DNMT3A mutation is associated with CDKN2B promoter methylation. We analyzed the characteristics of DNMT3A mutations including their clinical significance in AML and their influence on promoter methylation and CDKN2B expression.

Methods

A total of 142 adults, recently diagnosed with de novo AML, were enrolled in the study. Mutations in DNMT3A, CEBPA, and NPM1 were analyzed by bidirectional Sanger sequencing. We evaluated CDKN2B promoter methylation and expression using pyrosequencing and RT-qPCR.

Results

We identified DNMT3A mutations in 19.7% (N=28) of enrolled patients with AML, which increased to 29.5% when analysis was restricted to cytogenetically normal-AML. Mutations were located on exons from 8–23, and the majority, including R882, were found to be present on exon 23. We also identified a novel frameshift mutation, c.1590delC, in AML with biallelic mutation of CEBPA. There was no significant difference in CDKN2B promoter methylation according to the presence or type of DNMT3A mutations. CDKN2B expression inversely correlated with CDKN2B promoter methylation and was significantly higher in AML with R882H mutation in DNMT3A. We demonstrated that DNMT3A mutation was associated with poor AML outcomes, especially in cytogenetically normal-AML. The DNMT3A mutation remained as the independent unfavorable prognostic factor after multivariate analysis.

In hematologic malignancies, recurrent chromosomal abnormalities play a significant role in leukemogenesis [1]. Gene fusions and mutations, including those in CEBPA and NPM1, are major recurrent genetic abnormalities in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and have been established as major indicators for classification [2]. Further, genes involved in DNA methylation, including DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, and TET2, were found to be frequently mutated, especially in the cytogenetically normal karyotype (CN)-AML [3456]. DNA methylation, involved in the silencing of tumor-suppressor genes, has been associated with not only leukemogenesis but also with the clonal evolution of the myelodysplastic syndrome to AML [78]. Therefore, mutations in these genes may alter DNA methylation and may play an important role in disease pathogenesis in CN-AML. Somatic mutations in DNMT3A have been reported in approximately 20% and ~30%–35% of total AML and CN-AML, respectively [4]. Most DNMT3A mutations in AML have been found to be heterozygous and have been associated with changes in DNA methylation [910]. A missense mutation, R882H, located in the methyltransferase domain, has been found to be the most common mutation [1112]. R882H DNMT3A inhibits the expression of the wild-type DNMT3A and reduces the de novo methyltransferase activity, which results in the focal hypomethylation at specific CpGs throughout the genomes of AML cells [13].

CDKN2B, located in band 9p21 adjacent to CDKN2A, encodes a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, which forms a complex with the cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) or CDK6, and induces a G1-phase cell-cycle arrest by inhibiting CDK4/6. It also plays an important role in the regulation of cellular commitment of the hematopoietic progenitor cells and myeloid cell differentiation [14]. DNMT3A mutations in patients with AML have been reported to cause different degrees of the DNMT3A activity and have resulted in a heterogeneous DNA methylation (hyper-methylation or hypo-methylation) [15]. Various studies have shown conflicting data on the association of DNMT3A mutation and CDKN2B promoter methylation in AML. CDKN2B has been reported to be commonly silenced by deletion or hypermethylation in AML, but R882 DNMT3A has been reported to reduce the DNA methylation activity, causing a focal methylation loss [16]. A comprehensive understanding of the association of DNMT3A mutation with CDKN2B promoter methylation remains to be elucidated, along with the effect on its expression and clinical significance.

In this study, we analyzed the characteristics and clinical significance of DNMT3A mutations in AML and their influence on promoter methylation and expression of CDKN2B. In addition, we evaluated the changes of the R882H DNMT3A mutational burden after chemotherapy to understand its significance.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, the Catholic University of Korea (KC17SESE0768). A total of 142 adult patients, recently diagnosed with de novo AML at the Seoul St. Mary's Hospital from June 2015–February 2017, were enrolled in the study, consecutively. Patients who had undergone chemotherapy previously or had an antecedent hematologic disease, acute promyelocytic leukemia with PML-RARA, pure erythroid leukemia, acute megakaryoblastic leukemia, and acute leukemias of an ambiguous lineage were excluded. Diagnosis and classification of AML were based on the guidelines by WHO (2016) [17].

Bone marrow cells were aspirated from patients, cultured under unstimulated culture conditions for 1 d–2 d, and harvested. Karyotyping was carried out using the Giemsa banding techniques. At least 20 metaphase-cells were analyzed. Cytogenetic abnormalities were classified according to the 2016 guidelines of the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature [18]. Mutations in DNMT3A, CEBPA, and NPM1 were analyzed by a bidirectional Sanger sequencing using primers designed with Primer3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3/) and described in terms of GenBank sequences (DNMT3A, NM_022552.4; CEBPA, NM_004364.4; NPM1, NM_002520.6). Internal tandem duplications of FLT3 (FLT3-ITD) were analyzed, as per a previously reported method [19]. Primer sequences have been listed in Supplementary Table 1.

CpG methylation in the promoter region of CDKN2B was quantified using pyrosequencing. The EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used for bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA; the PyroMark Gold Q96 Reagents (Qiagen) and the PyroMarkTM Q96 ID instrument (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden) were used for pyrosequencing, according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of seven CpG sites were analyzed per sample. The primers for the analysis of CDKN2B-specific CpG regions were the same as those used by our group in a previous study [20].

CDKN2B mRNA expression was measured by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) using TaqMan (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was isolated from the bone marrow aspirates using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Taqman probes for CDKN2B (HS00793225_m1) with transcript p15, and the endogenous control (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH); Hs99999905_m1) were used. All reactions were performed using an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression levels were calculated based on the 2−ΔΔCt×1,000 method, after normalization to the transcript levels of GAPDH.

Primers and probes were derived from RefSeq NM_022552.4 using the OLIGO ver. 7.51 software (Molecular Biology Insights, Inc., Cascade, CO, USA). The PCR reaction was carried out as follows: 2 min at 50℃, 10 min at 95℃, 50 cycles of 15 s at 95℃, and 1 min at 60℃ on a Mx3000PTM Real-Time PCR system (Stratagene, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using the MxPro version 4.10 (Stratagene). DNMT3A mutant allele burden was calculated as a ratio of the copy number of DNMT3A mutant to that of β-actin. The analytical performance of the quantitative PCR assay has been described in the Supplementary data.

The correlations between parameters compared in contingency tables were found using the Chi-squared (χ2) test. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to estimate overall survival (OS) and to compare differences between survival curves. OS was measured from date of initial diagnosis to the date of death, or last follow-up, from any cause. The multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression method was used to analyze independent prognostic factors for OS. The variables, including age; karyotype; presence of mutations in DNMT3A and FLT3-ITD; subgroup of AML, such as a biallelic CEBPA mutation with a mutated NPM1, and AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (AML-MRC), were used as covariates. All statistical analyses were done using MedCalc (MedCalc Software, Ltd., Ostend, Belgium) and the level of statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

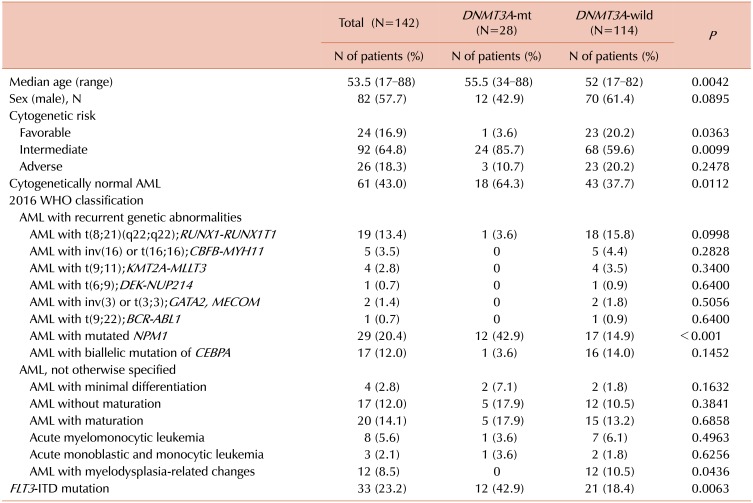

Among the 142 patients enrolled with de novo AML, 82 were males and 60 were females. The median age was 53.5 years (range, 17–88 yr). DNMT3A mutations were identified in 28 patients (19.7%). Patients with DNMT3A mutations were older than those with wild type DNMT3A (median age, 55.5 vs. 52 yr; P=0.0042). For recurrent genetic abnormalities, DNMT3A mutations were not detected in patients with fusions, except for one with t(8;21) and Q842R DNMT3A. On the other hand, DNMT3A mutations were more commonly detected in patients with NPM1 mutations (P<0.001). DNMT3A mutations were more frequently identified in patients with cytogenetically normal (CN)-AML (P=0.0112). In addition, the incidence of DNMT3A mutations was higher in patients with FLT3-ITD mutations than in those without FLT3-ITD mutations (P=0.0063) (Table 1).

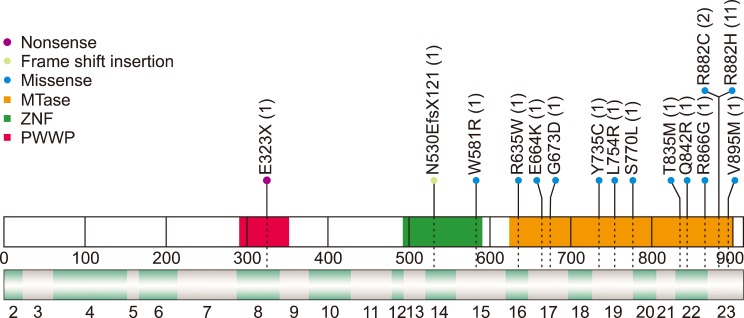

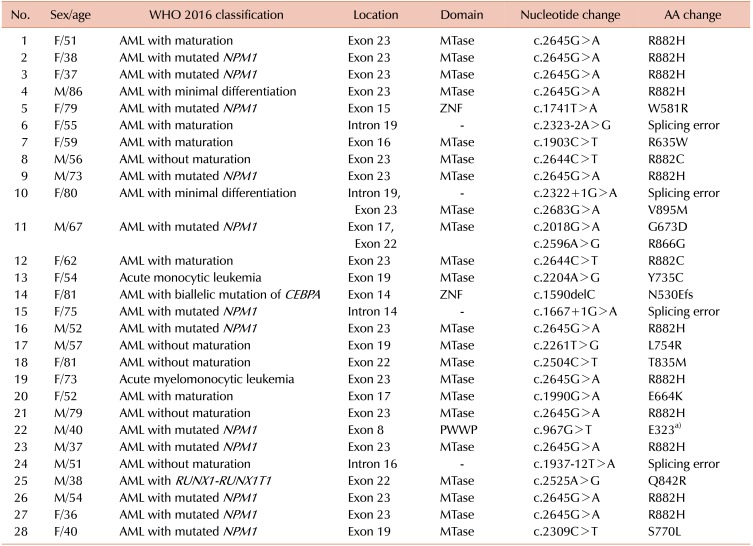

We identified 19 different DNMT3A mutations in 28 patients with AML (Fig. 1, Table 2); 13 missense mutations, one nonsense mutation, one deletion mutation, and four splicing mutations. The most common mutation was c.2645 G>A (R882H, N=11), followed by c.2644C>T (R882C, N=2). Mutations were located in all exons, from exon 8 to exon 23, and the majority (N=14), including R882 mutations, occurred on exon 23. We identified a novel frameshift mutation, c.1590delC [p.(Asp530Glufs*121)], in AML with a biallelic mutation of CEBPA.

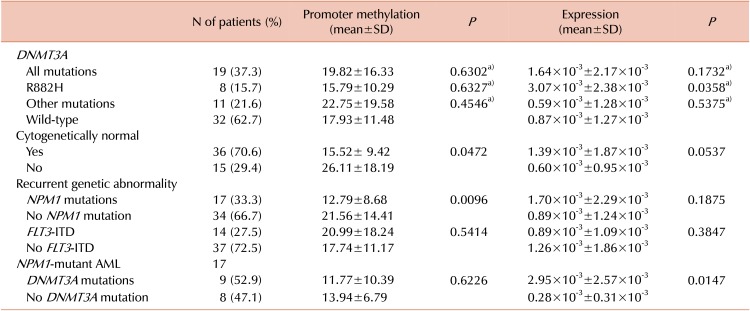

We measured the value of CDKN2B promoter methylation using pyrosequencing and evaluated the association of methylation with DNMT3A mutation (N=51). The average value of CDKN2B promotor methylation was 18.63±13.36%. It was lower in CN-AML and in patients with NPM1 mutations (P=0.0472 and P=0.0096, respectively). There was no significant difference of CDKN2B promoter methylation, based on the presence or type of DNMT3A mutations.

We also measured CDKN2B expression using RT-qPCR and analyzed its association with CDKN2B promoter methylation. CDKN2B expression was inversely correlated with CDKN2B promoter methylation (R=−0.50, P<0.001). CDKN2B expression was significantly higher in R882H DNMT3A AML than in DNMT3A wild-type AML (P=0.0358) (Table 3). In addition, patients with R882H DNMT3A showed higher CDKN2B expression compared to patients with AML and other DNMT3A mutations (P=0.0094). Among patients with the NPM1 mutations (N=17), CDKN2B promoter methylation was not different between the DNMT3A mutated and the wild-type AML. CDKN2B expression was significantly different in accordance with the NPM1 mutation with the DNMT3A status (Table 3).

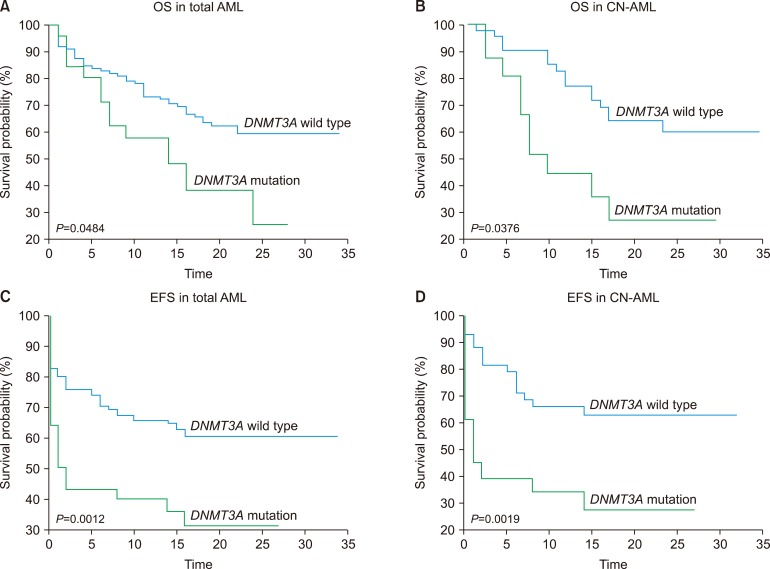

DNMT3A mutated AML showed poor OS and event-free survival (EFS), compared to that from the DNMT3A wild-type AML (P=0.0484 and P=0.0012, respectively) (Fig. 2A, B). In addition, we analyzed the prognostic effect of DNMT3A mutations in CN-AML and found that the DNMT3A-mutated CN-AML showed poorer OS and EFS compared to that shown by the DNMT3A wild-type CN-AML (P=0.0376 and P=0.0019) (Fig. 2C, D).

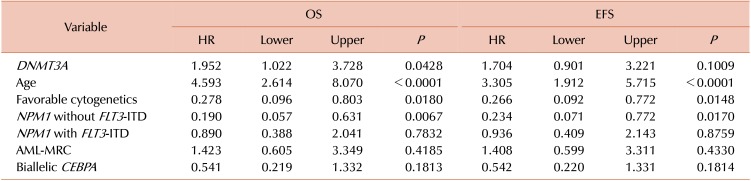

We performed multivariate analysis with variables that included the DNMT3A mutation, age, favorable cytogenetics, the NPM1 mutation without FLT3-ITD, the NPM1 mutation with FLT3-ITD, a biallelic CEBPA mutation, and AML-MRC. Among these, old age (>60 yr) remained an independent unfavorable prognostic factor. For OS, DNMT3A mutations remained an independent unfavorable prognostic factor. However, DNMTA mutations did not show significant difference in the prognosis of EFS. Favorable cytogenetics and presence of the NPM1 mutation in the absence of FLT3-ITD were independent favorable prognostic factors (Table 4).

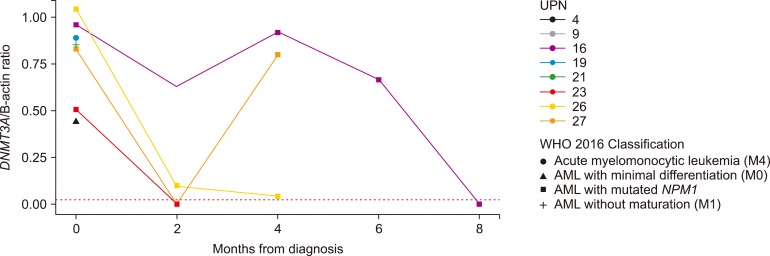

We performed quantitative analysis of the R882H mutation in DNMT3A in 17 samples from eight patients. We used DNMT3A/β-actin ratio as quantitative R882H mutation index. The average value of the mutation (DNMT3A/β-actin ratio) was 0.81±0.22 at the time of diagnosis. Sequential follow-up was done for four patients (UPN 16, 23, 26, and 27) of AML with NPM1 mutation. The DNMT3A mutant burden decreased after induction chemotherapy; however, the reduced value was variable. DNMT3A mutations disappeared after induction chemotherapy in the patient, UPN23. Patient UPN27 showed a marked decrement of the mutant burden in complete remission status (0.39% of the initial value), but it increased up to the initial value at relapse (96.57%). Patient UPN16 showed persistent DNMT3A mutations after achieving morphological CR (65.16%, 94.46%, and 69.34%). The patient received an allogeneic stem-cell transplantation, after which the DNMT3A mutation disappeared. In patient UPN26, the DNMT3A mutant burden decreased to 8.70% and 4.16% in the CR status (Fig. 3).

DNMT3A is a de novo DNA methyltransferase that catalyzes the addition of a methyl group to the cytosine residue of CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine. DNA methyltransferase plays a significant role in epigenetically regulated gene expression and repression. In this study, we identified DNMT3A mutations in 19.7% of the enrolled patients with AML, which increased to 29.5% when restricted to the CN-AMLs. For the WHO 2016-based classification, DNMT3A mutations were frequently accompanied in AML with NPM1 mutations and were less frequently observed in AML-MRC. Noteworthy, we found a Q842R mutation in AML with t(8;21). To our knowledge, AML with t(8;21), inv(16), and inv(3)/t(3;3) rarely harbored the DNMT3A mutation, and this is the first reported case of DNMT3A mutation in AML with t(8;21) [52122]. R882H DNMT3A was the most commonly found mutation, consistent with previous reports [2324]. We also detected a novel frameshift mutation located on ZNF.

Previously, a strong correlation between decreased DNA methylation and DNMT3A mutations in the methylation of 12 select tumor suppressor genes, including CDKN2B, has been reported [9]. However, we did not find a significant difference in CDKN2B promoter methylation, in patients with DNMT3A mutations, although promoter methylation was low in AML with R882H DNMT3A. Moreover, methylation levels were significantly lower in CN-AML and in AML with the NPM1 mutations, which frequently accompanied the DNMT3A mutations. These differences may be due to the presence of heterogeneous DNMT3A mutations, a limited number of patients with mutations, and the technique used to determine the level of methylation, in the present study. Previously, various techniques, including Southern blotting, methylation specific PCR, and pyrosequencing, have been used to determine CDKN2B methylation. However, no standardized method has been identified; therefore, the methylation was heterogeneous with inter-individual differences [14].

Moreover, the presence of CDKN2B methylation is not always associated with reduced expression of CDKN2B mRNA; therefore, it will be important to investigate the expression of CDKN2B in AML with various DNMT3A mutations. We found that CDKN2B expression was inversely correlated with CDKN2B promoter methylation. Notably, patients with R882H DNMT3A showed higher CDKN2B expression compared to those with the wild-type DNMT3A or other DNMT3A mutations.

In addition, we observed that CDKN2B expression showed significant difference in accordance with the NPM1 mutation with the DNMT3A mutation status. However, in this study, the number of cases analyzed were limited and further studies will be necessary to determine whether the statistical difference arises from DNMT3A R882H (Table 3).

We demonstrated that the DNMT3A mutations were associated with poor outcomes in AML, especially in CN-AML. Multivariate analysis results showed that DNMT3A mutations remained a factor affecting poor OS. Previously, DNMT3A mutations have been shown to be independently associated with poor outcomes [422]; however, there is no consensus on the effect of DNMT3A mutations [25]. It seems worthwhile to evaluate their effect on prognosis in the presence of other known prognostic markers and therapeutic strategies, such as the hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation [2627]. Studies that have investigated the suitability of DNMT3A mutations for MRD monitoring, have shown the persistence of DNMT3A mutations during CR [2829]. However, pre-leukemic hematopoietic clones with DNMT3A mutations may be resistant to leukemic therapy and may lead to further clonal expansion during remission, and may eventually cause recurrent disease [30]. We have developed a qPCR method to measure the R882H DNMT3A allele burden accurately. The mutant allele burden was variable at the time of diagnosis and changed differently during CR. A recent study has shown that the R882 DNMT3A mutant allele burden determined AML prognosis [31]. Although no clear association between the persistence of DNMT3A mutations and clinical outcomes has been reported, a large prospective study, using a suitable method to measure DNMT3A mutations, will clarify the significance of the initial mutant allele burden and its change after treatment.

Notes

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no. HI18C0480) and the research fund of the Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea.

References

1. Betz BL, Hess JL. Acute myeloid leukemia diagnosis in the 21st century. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010; 134:1427–1433. PMID: 20923295.

2. Figueroa ME, Lugthart S, Li Y, et al. DNA methylation signatures identify biologically distinct subtypes in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2010; 17:13–27. PMID: 20060365.

3. Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Della Valle V, et al. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:2289–2301. PMID: 19474426.

4. Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:2424–2433. PMID: 21067377.

5. Ley TJ, Miller C, Ding L, et al. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:2059–2074. PMID: 23634996.

6. Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1058–1066. PMID: 19657110.

7. Jang W, Park J, Kwon A, et al. CDKN2B downregulation and other genetic characteristics in T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Exp Mol Med. 2019; 51:4.

8. Jiang Y, Dunbar A, Gondek LP, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation is a dominant mechanism in MDS progression to AML. Blood. 2009; 113:1315–1325. PMID: 18832655.

9. Hájková H, Marková J, Haškovec C, et al. Decreased DNA methylation in acute myeloid leukemia patients with DNMT3A mutations and prognostic implications of DNA methylation. Leuk Res. 2012; 36:1128–1133. PMID: 22749068.

10. Qu Y, Lennartsson A, Gaidzik VI, et al. Differential methylation in CN-AML preferentially targets non-CGI regions and is dictated by DNMT3A mutational status and associated with predominant hypomethylation of HOX genes. Epigenetics. 2014; 9:1108–1119. PMID: 24866170.

11. Im AP, Sehgal AR, Carroll MP, et al. DNMT3A and IDH mutations in acute myeloid leukemia and other myeloid malignancies: associations with prognosis and potential treatment strategies. Leukemia. 2014; 28:1774–1783. PMID: 24699305.

12. Yan XJ, Xu J, Gu ZH, et al. Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011; 43:309–315. PMID: 21399634.

13. Russler-Germain DA, Spencer DH, Young MA, et al. The R882H DNMT3A mutation associated with AML dominantly inhibits wild-type DNMT3A by blocking its ability to form active tetramers. Cancer Cell. 2014; 25:442–454. PMID: 24656771.

14. De Braekeleer M, Douet-Guilbert N, De Braekeleer E. Prognostic impact of p15 gene aberrations in acute leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017; 58:257–265. PMID: 27401303.

15. Sandoval JE, Huang YH, Muise A, Goodell MA, Reich NO. Mutations in the DNMT3A DNA methyltransferase in acute myeloid leukemia patients cause both loss and gain of function and differential regulation by protein partners. J Biol Chem. 2019; 294:4898–4910. PMID: 30705090.

16. Spencer DH, Russler-Germain DA, Ketkar S, et al. CpG island hypermethylation mediated by DNMT3A is a consequence of AML progression. Cell. 2017; 168:801–816.e13. PMID: 28215704.

17. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016; 127:2391–2405. PMID: 27069254.

18. McGowan-Jordan J, Simons A, Schmid M, editors. ISCN 2016: An International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (2016). Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger;2016.

19. Kim Y, Lee GD, Park J, et al. Quantitative fragment analysis of FLT3-ITD efficiently identifying poor prognostic group with high mutant allele burden or long ITD length. Blood Cancer J. 2015; 5:e336. PMID: 26832846.

20. Kwon A, Kim Y, Kim M, et al. Tissue-specific differentiation potency of mesenchymal stromal cells from perinatal tissues. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:23544. PMID: 27045658.

21. Jiang D, Hong Q, Shen Y, et al. The diagnostic value of DNA methylation in leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e96822. PMID: 24810788.

22. Ribeiro AF, Pratcorona M, Erpelinck-Verschueren C, et al. Mutant DNMT3A: a marker of poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012; 119:5824–5831. PMID: 22490330.

23. Hou HA, Kuo YY, Liu CY, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: stability during disease evolution and clinical implications. Blood. 2012; 119:559–568. PMID: 22077061.

24. Marcucci G, Metzeler KH, Schwind S, et al. Age-related prognostic impact of different types of DNMT3A mutations in adults with primary cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30:742–750. PMID: 22291079.

25. Brunetti L, Gundry MC, Goodell MA. DNMT3A in leukemia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017; 7:a030320. PMID: 28003281.

26. Ahn JS, Kim HJ, Kim YK, et al. DNMT3A R882 mutation with FLT3-ITD positivity is an extremely poor prognostic factor in patients with normal-karyotype acute myeloid leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016; 22:61–70. PMID: 26234722.

27. Tang S, Shen H, Mao X, et al. FLT3-ITD with DNMT3A R882 double mutation is a poor prognostic factor in Chinese patients with acute myeloid leukemia after chemotherapy or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2017; 106:552–561. PMID: 28616699.

28. Bhatnagar B, Eisfeld AK, Nicolet D, et al. Persistence of DNMT3A R882 mutations during remission does not adversely affect outcomes of patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2016; 175:226–236. PMID: 27476855.

29. Jeziskova I, Musilova M, Culen M, et al. Distribution of mutations in DNMT3A gene and the suitability of mutations in R882 codon for MRD monitoring in patients with AML. Int J Hematol. 2015; 102:553–557. PMID: 26290145.

30. Shlush LI, Zandi S, Mitchell A, et al. Identification of preleukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature. 2014; 506:328–333. PMID: 24522528.

31. Yuan XQ, Chen P, Du YX, et al. Influence of DNMT3A R882 mutations on AML prognosis determined by the allele ratio in Chinese patients. J Transl Med. 2019; 17:220. PMID: 31291961.

Fig. 2

Prognostic factors for patients with acute myeloid leukemia. (A) OS and (C) EFS in total patients with AML. (B) OS and (D) EFS in patients with CN-AML. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for OS in 142 total patients with AML (P=0.0484) and (B) 61 patients with CN-AML (P=0.0376). (C) EFS curve in total 142 patients with AML (P=0.0012) and (D) EFS curve in 61 patients with CN-AML (P=0.0019).

Fig. 3

The results of quantitative analysis of DNMT3A R882H in eight patients with acute myeloid leukemia with regard to the WHO 2016 classification.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download