This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Ovarian pregnancies comprise approximately 3% of ectopic pregnancies. Moreover, ovarian pregnancies in the second trimester are extremely rare. We herein present a case of ruptured ovarian pregnancy in the second trimester. A 26-year-old Asian woman presented to our hospital complaining of an abrupt mental change. She was pregnant; however, she had not been receiving antenatal care. Her initial vital signs were unstable, and pelvic ultrasound revealed pelvic fluid collection. We analyzed the hemoperitoneum and performed exploratory laparotomy. When her abdomen was opened, we observed that her right ovary was ruptured. Placental cord insertion originated from the ovary, and a fetus was found in the pelvic cavity. The ovarian pregnancy was detected in a delayed state. Pregnant women require appropriate antenatal care, and pelvic ultrasound should be performed in the second trimester to ensure that the fetus is in the intrauterine cavity.

Go to :

Keywords: Pregnancy, ovarian, Pregnancy trimester, second

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy, which is the implantation of the fetus in a site other than the uterine cavity, is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in women of reproductive age. Ectopic pregnancy is approximately 2% of the total pregnancies, and ovarian pregnancies account for less than 3% of all cases of ectopic pregnancy [

1234]. An ectopic pregnancy is usually diagnosed in the first trimester, when antenatal care is initiated and patients present with symptoms, such as abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding. Therefore, an ovarian pregnancy in the second trimester is extremely rare. Here, we present a case of ruptured ovarian pregnancy in the second trimester.

Go to :

Case report

A 26-year-old Asian woman (gravida 2, para 1) presented to the emergency room with an abrupt mental change. She was pregnant; however, she had not been receiving antenatal care, and the period of amenorrhea was unknown. No specific symptoms were noted before she visited the hospital.

The patient presented with coma, and the pulse oximeter revealed an oxygen saturation of 53% and absence of spontaneous breathing. She was intubated and provided with ventilator support. Her initial vital signs were unstable (blood pressure, 80/40 mmHg; body temperature, 34.0°C; heart rate, 137 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 14 breaths per minute).

Initially, chest disease including pulmonary embolism was suspected because she could not breathe by herself and there was no indication of surgical abdomen. The emergent chest computed tomography revealed no lesions in the lungs; however, her abdomen became distended 30 minutes later. Secondly, we suspected hemoperitoneum with active bleeding. Pelvic ultrasound revealed pelvic fluid collection. The blood tests revealed a hemoglobin level of 4.8 g/dL; white blood cell count, 4,480/µL; and platelet count, 239,000/µL. The prothrombin time (PT) was prolonged to 19.4 seconds (range: 11.8–14.3 seconds), and the PT/international normalized ratio was 1.72.

On immediate exploratory laparotomy, massive bloody fluid was found in her pelvic cavity. Following removal of the fluid, we detected that a placental cord insertion originated from the ovary (

Fig. 1A), a normal sized uterus was seen, and a fetus was found dead in the pelvic cavity (

Fig. 1B). The fallopian tube was separated from the ovary (

Fig. 1C). Ruptured ovarian pregnancy was suspected based on the surgical findings. We performed a right oophorectomy; however, oozing from multiple sites during the surgery persisted due to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) along with excessive bleeding. After the bleeding was controlled, the oozing gradually decreased and the operation was completed. In the operation room, 22 packs of red blood cell, 12 packs of fresh frozen plasma, 10 packs of platelet concentrates, and 10 packs of cryoprecipitate were transfused into the patient because of bleeding and DIC. Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for close monitoring. Twelve hours post-operatively, her urine output was approximately 70 cc (5.8 cc/hour), and her creatinine level was elevated to 1.69 mg/dL (reference: 0.5–0.9 mg/dL). Acute kidney injury due to hypovolemic shock was presumed, and the patient was administered diuretics to maintain an urine output of 40 cc/hour. At 3 days post-operatively, the urine output increased to 150 cc/hour, and diuretics were discontinued. Her creatinine level increased to 7.51 mg/dL. at 8 days post-operatively, and then decreased spontaneously. Acute kidney injury was relieved, and the patient was discharged 18 days post-operatively. The actual weight of the dead fetus was 600 g.

| Fig. 1 (A) Placenta originating from ovary_the placental cord insertion is seen to originate from the ovary. (B) Cord insertion to ovary and fetus in pelvic cavity_fetus (a) occupies the position of ovary (b), and the uterus (c) is intact. (C) Fallopian tube is seen separated from the ovary_ovary (a) connected to the uterus (b) by ovarian ligament (small arrow) and fallopian tube (large arrow) is seen separated from the ovary.

|

Go to :

Discussion

Here, we present a rare case of ruptured ovarian pregnancy that occurred in the second trimester. Ectopic pregnancy is defined as the implantation of a fertilized ovum outside the uterine cavity. The morbidity and mortality of ectopic pregnancies are high among women of reproductive ages [

5]. Important risk factors in ectopic pregnancy include a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, prior ectopic pregnancy, insertion of an intrauterine device, tubal surgery, and tubal ligation [

67]. Recently, the prevalence of ectopic pregnancies has increased due to more accurate diagnostic tools and an increase in assisted reproductive technologies [

8].

Ectopic pregnancy is mostly diagnosed in the first trimester. Ovarian pregnancy usually ends in rupture during the first, second, and third trimesters in 91%, 5.3%, and 3.7% of cases. However, there have been a few reported cases of full-term ovarian pregnancies [

9].

Physicians can detect ectopic pregnancies by performing pelvic ultrasound and examining serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin levels [

10]. Acute abdominal pain is the most common symptom in patients with ruptured ectopic pregnancy, and there have been many cases where the ectopic pregnancy was diagnosed because of acute abdominal pain when the patient was unaware of the pregnancy. There are 2 options for the management of an ectopic pregnancy: medically using methotrexate or surgically by removal of the ectopic mass [

1112]. In a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, the patient usually experiences hemodynamic instability due to the bleeding from the rupture site. Therefore, physicians prefer the surgical option for the management of a ruptured ectopic pregnancy [

12]. In an ovarian pregnancy, ovarian cystectomy or ovarian wedge resection is a common surgical procedure [

1314]. In 1878, Spiegelberg described 4 diagnostic criteria for ovarian pregnancies [

15]: intact fallopian tube on the affected side, fetal sac occupying the position of the ovary, connection of ovary to the uterus by the ovarian ligament, and histological confirmation of ovarian tissue in the gestational sac wall.

The patient arrived at the hospital in an altered mental state without acute abdominal pain, which is the most common symptom of an ectopic pregnancy. It is possible that the mental state was due to hemodynamic instability that are sometimes observed in cases of ruptured ectopic pregnancy. However, based on the abrupt mental change and absence of pain, we considered neurologic problems such as syncope, seizure, and brain damage. Initially, because she presented with low oxygen saturation and inability to breathe, we suspected cardiopulmonary issues. The diagnosis of ruptured ectopic pregnancy was challenging due to the absence of common symptoms, such as acute abdomen, and the presence of an altered mental change, which is uncommon.

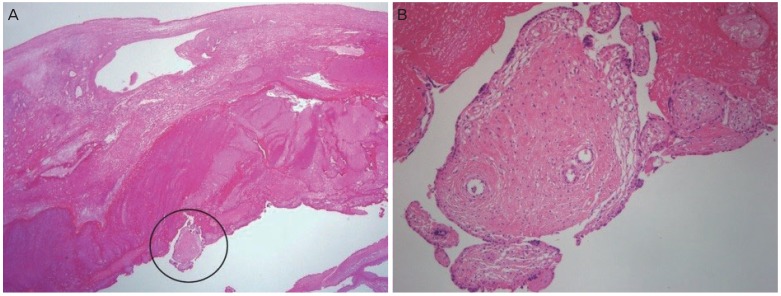

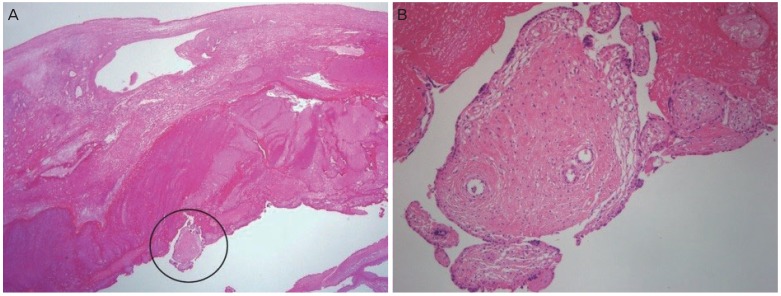

In our case, we confirmed the ovarian pregnancy through gross and microscopic examination of the specimen, which met all the criteria described by Spiegelberg, including ovarian tissues in the gestational sac wall (

Fig. 2). DIC resulted in continuous bleeding of the operation site after the fetus was removed. As a result, we operated using techniques for oophorectomy instead of techniques for cystectomy or wedge resection.

| Fig. 2 Histological finding of oophorectomy_chorionic villi tissues in the wall of ovary, high magnification (×40) (A) and low magnification (×100) (B).

|

Ruptured ovarian pregnancy is usually accompanied by symptoms such as acute abdomen, and it is usually found in the first trimester of pregnancy. However, if the ovarian pregnancy continues to an unruptured state, it can progress and undergo delayed rupture after the first trimester. Ectopic pregnancies can be detected early if pregnant women undergo an antenatal care program. At a minimum, an ultrasound should be performed to ensure that the fetus is in the intrauterine cavity in cases lacking antenatal care.

Go to :

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to our patient for providing informed consent for the publication of this case report.

Go to :

Notes

Go to :

References

1. Seeber BE, Barnhart KT. Suspected ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 107:399–413. PMID:

16449130.

2. Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, Pouly JL, Job-Spira N. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10 year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod. 2002; 17:3224–3230. PMID:

12456628.

3. Grimes HG, Nosal RA, Gallagher JC. Ovarian pregnancy: a series of 24 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1983; 61:174–180. PMID:

6823359.

4. Hallatt JG. Primary ovarian pregnancy: a report of twenty-five cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982; 143:55–60. PMID:

7081312.

5. Chow WH, Daling JR, Cates W Jr, Greenberg RS. Epidemiology of ectopic pregnancy. Epidemiol Rev. 1987; 9:70–94. PMID:

3315720.

6. Ankum WM, Mol BW, Van der Veen F, Bossuyt PM. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 1996; 65:1093–1099. PMID:

8641479.

7. Murray H, Baakdah H, Bardell T, Tulandi T. Diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy. CMAJ. 2005; 173:905–912. PMID:

16217116.

8. Seo MR, Choi JS, Bae J, Lee WM, Eom JM, Lee E, et al. Preoperative diagnostic clues to ovarian pregnancy: retrospective chart review of women with ovarian and tubal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017; 60:462–468. PMID:

28989923.

9. Prabhala S, Erukkambattu J, Dogiparthi A, Kumar P, Tanikella R. Ruptured ovarian pregnancy in a primigravida. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015; 5:151–153. PMID:

26097828.

10. Tuomivaara L, Kauppila A, Puolakka J. Ectopic pregnancy--an analysis of the etiology, diagnosis and treatment in 552 cases. Arch Gynecol. 1986; 237:135–147. PMID:

3485406.

11. Barnhart KT, Gosman G, Ashby R, Sammel M. The medical management of ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis comparing “single dose” and “multidose” regimens. Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 101:778–784. PMID:

12681886.

12. Stovall TG, Ling FW. Ectopic pregnancy. Diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms minimizing surgical intervention. J Reprod Med. 1993; 38:807–812. PMID:

8263872.

13. Van Coevering RJ 2nd, Fisher JE. Laparoscopic management of ovarian pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1988; 33:774–776. PMID:

2971805.

14. Tinelli A, Hudelist G, Malvasi A, Tinelli R. Laparoscopic management of ovarian pregnancy. JSLS. 2008; 12:169–172. PMID:

18435892.

15. Elwell KE, Sailors JL, Denson PK, Hoffman B, Wai CY. Unruptured second-trimester ovarian pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015; 41:1483–1486. PMID:

26017365.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download