Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to report the surgical outcomes of postoperative management of ice-cooling combined with moist-open dressing and intravenous prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) injection. Ice cooling as postoperative management was also discussed.

Methods

Forty-one fingertip amputation of 38 patients between January 2007 and December 2017 were investigated retrospectively. Fingertip amputations were managed with postoperative ice bag application for 72 hours followed by moist open dressing and PGE1 injection.

Results

Twenty-five composite grafts (61.0%) survived with complete healing at 8 weeks after surgery, with favorable outcomes in cases with low injury level (type I, 82.3%) and guillotine injury (77.8%). A higher survival rate was significantly correlated with female sex, guillotine injury, injury without osseous tissue (type I), and cold outdoor temperature (p<0.05). Multivariate analysis revealed that differences between types I and III injuries, injury mode, and outdoor temperature were independent clinical parameters associated with composite graft survival.

Conclusion

The present study reported comparable results with postoperative ice cooling in cases with low injury level, guillotine injury, and low outdoor temperature. Prospective studies on the specific parameters of ice cooling and standards of manageable postoperative care should be conducted to enhance survival.

The fingertips are the most distal part of the upper extremities, and its composite tissues include volar dermocutaneous tissue, the head of the distal phalanx, nail, and nailbed. Fingertip amputation has been managed with several methods including microvascular free tissue transfer, local flap and composite grafting. Since Komatsu and Tamai1 have reported successful microvascular finger replantation in 1968, many hand surgeons have established high replantation success rate. Although microvascular anastomosis may be an ideal reconstruction option, it is difficult and unreliable because of small vessel diameter and the unavailability of candidate vessels.

Composite grafting, which is the reattachment of an amputated stump to the proximal finger without microvascular anastomosis, is a simple and quick reconstruction method. With its highly variable surgical outcomes (52.6%–93.5%), appropriate postoperative management was tried to improve the results2. Hirase3 first utilized lipo-prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) with ice-cooled grafting at the postoperative period, which resulted in successful reattachment. Eo et al.4 also showed satisfactory results of composite grafting with intravenous PGE1 injection and stump cooling of the fingers5. Son et al.6 maintained a moist condition and used loose dressing during the postoperative period and gained comparable result of complete survival rate.

The purpose of the present study was to report the surgical outcomes of postoperative management with graft ice cooling and emphasize the milieu factors for composite grafting.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB No. 2018-08-005-001) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The need for informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

We retrospectively analyzed the data of patients with fingertip amputation who underwent composite grafting between January 2007 and December 2017. The exclusion criteria for this study were the following: composite grafting performed over 12 hours after injury, as irreversible tissue damage is highly possible and may lead to result bias; cases with any microvascular anastomosis during the reattachment procedure; more injuries proximal to the fingertip; lack of medical record less than 2 months after surgery. Patient information including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), underlying hypertension, whether smoker or not, location of injury, and injury level and mode was collected. The injury level was categorized according to the Das classification: type I, no distal phalangeal bone injury; type II, injury up to one-third of the distal phalangeal bone; type III, more distal phalangeal bone injury. Additionally, based on the theory that external temperature may have an effect on tissue destruction during the preoperative period and before revascularization, the outdoor temperature on the injury date was investigated7. We determined the minimum and maximal temperatures on the date of injury and compared the survival rate between patients who were injured at warm temperature (minimal temperature ≥20℃ or maximal temperature ≥24℃) and the rest of the patients who were injured at cooler temperature. Ice bag was applied for 72 hours postoperatively. Additionally, intravenous PGE1 was administered from postoperative days 3 to 10 day with moist open dressing without compression. Graft survival was defined as complete engraftment without tissue loss, or partial loss but healed within 8 weeks after surgery. Graft failure was defined as complete tissue necrosis that needed other reconstruction procedures such as free flap or stump revision or partial loss that needed more than 8 weeks of postoperative wound care.

All operations were performed by the corresponding author. The amputated stumps were temporarily stored in plastic bag with saline gauze cover and kept in a refrigerator 4℃ to prevent the stump from tissue degeneration. In aseptic condition, the amputated fingers and stumps were repetitively irrigated and irregular wound margin was debrided. If the amputated stump contained part of the distal phalanx (less than one-fourth), the osseous tissue was removed from the stump using Metzenbaum scissors and the proximal part of the distal phalanx was rasped. Rongeur or other surgical instruments that could inflict blunt damage to tissue leading to destruction of vascularity were not used. When the amputated stump had more than one-fourth of the distal phalanx, simple reattachment without bone removal was performed and one or more Kirschner wire fixation was performed. Bleeding control was not always implemented but if bleeding would result in hematoma formation on the reattachment surface, accurate hemostasis was performed using bipolar electrocauterization. The skin was closed with 5-0 nylon. Concomitant nail bed injury was closed with 7-0, Vicryl and the extracted nail was reinserted to the eponychium and fixed by 4-0 Prolene.

An ice bag was applied for 72 hours postoperatively on the operated finger distally to cool down the graft site. Patients were instructed to apply the ice bag on the most distal area and to handle it gently to avoid further trauma. Most of the patients were wearing a short arm splint; thus, the ice bag was applied on the alternative side of the splint. An elastic net bandage (Surgifix; BSN Medical, Hamburg, Germany) was used when the patient was sleeping or unable to apply the ice bag by himself or herself in order to hold the ice bag near the operation site. Applying ice on the graft was prohibited to avoid freezing it.

Intravenous PGE1 (10 µg/2 mL, mixed with 500 mL normal saline; Eglandin; Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Osaka, Japan) was administered 72 hours postoperatively, which was the estimated start of angiogenesis, and was continued for 7 days. If the patient preferred to stay in the hospital, PGE1 was intravenously administered for 3 more days.

The fingertips were dressed with foam materials without compression and with open space distally. Patients were encouraged to apply 0.5 mL of antibiotic ointment (Terramycin Ophthalmic Ointment; Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) through the space 10 times a day to keep the grafted stump moist (Fig. 1). However, an excessively moist condition was avoided to prevent maceration. The wound was dressed twice a day during the first 3 days postoperatively in order to familiarize the patient with the adequate amount of the ointment. The moist open dressing was continued until the day when the stitches were removed. All stitches were removed between postoperative weeks 2 and 3 if tissue necrosis did not hinder suture site engraftment. After stitch removal, wet closed foam dressing was applied on the open wound twice a week until complete healing.

The graft site was cleaned and evaluated daily for fingertip color, eschar formation, and whether it was kept moist. Smoking was completely prohibited right after surgery. A short arm splint was applied if there was accompanying bone injury. If any partial congestive color was noticed, some stitches were removed to help the drainage from the contact surface.

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows ver. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The correlations between survival rate and sex, hypertension, smoking, injured finger, injury level, injury mode, and outdoor temperature were analyzed using Pearson chi-square test. The correlations between survival rate and age and BMI were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U-test. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine the final independent risk factors.

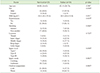

Forty-one fingertip amputations in 38 patients (28 male and 10 female) were included in this study. The demographic characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. According to the Das classification, injuries were classified as type I (n=17, 41.5%), type II (n=10, 24.4%), or type III (n=14, 34.1%)8. Twenty-one cases were due to guillotine injury and had clean-cut amputation surface, whereas 20 cases were due to crushing injury. Twentyfive composite grafts (61.0%) survived with complete healing at 8 weeks after surgery (Fig. 2, 3). Among 16 grafts that regarded to have engraftment failure, 11 cases completely healed with partial debridement and further dressing, 4 cases had to undergo thenar flap reconstruction, and 1 case underwent abdominal flap reconstruction. Tissue survival was significantly correlated with female sex, guillotine injury, injury without osseous tissue (type I), and cold outdoor temperature (p<0.05) (Table 2). The multivariate analysis revealed three independent clinical parameters associated with favorable surgical outcome: injury level type I versus type II (odds ratio [OR] 14.586; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.408–151.070, p=0.025), guillotine injury (OR 11.782, 95% CI 1.618–85.776, p=0.015), and cold outdoor temperature (OR 10.029, 95% CI 1.391–72.295, p=0.022) (Table 3).

Composite grafting is the nonmicrovascular reattachment of soft tissue usually including skin and adipose tissue9. It can be used for fingertip amputation if replantation is impossible10. Many authors had successful outcomes in children, but composite grafting in adult patients has a relatively low survival rate8. It may be attributed to the limited vascularity of the adipose tissue in stump, which leads to limited microvascular anastomosis.

In our study, 41 fingertip amputations were managed with ice bag application for 72 hours postoperatively. Cooling of the grafted stump can be helpful for the survival rate until angiogenesis begins because of the following reasons. First, exposure of the hypoperfused stump to lower temperature delays the generation of radical oxygen3. Radical oxygen, which has a strong oxidizing power, attacks and destroys normal tissues11, and exposure to more radical oxygen accelerates tissue degeneration. Second, the metabolism of cooled tissue may decrease as the speed of the whole cell cycle decreases. This may preserve the stump from cellular destruction until the new vessel structure grows.

However, freezing of the stump would not be helpful because it prevents neovascularization to the stump. This means that the stump should be cooled down to 0℃. To fulfill that condition, we chose to apply an ice bag over the fingertip but not immerse it in ice.

For further minor postoperative care, after 72 hours, the ice bag was removed to prevent vascular contracture of newly developing vessels, and PGE1 was administered to help angiogenesis for 7 days. Cooling was prohibited during this period because it might cause vasoconstriction of newly developed vessels, as angiogenesis is known to start 72 hours after contact between the edges of the wound3. PGE1 has been reported to help composite graft survival by promoting angiogenesis3. Moist open dressing was chosen because it can help the drainage from the wound and prevent dermal necrosis, which can cause irreversible tissue degeneration of the stump6. Angiogenesis can be also accelerated by moist condition12, as shown by the increased number of vessel in porcine skin models with moist condition13.

In a previous moist open dressing study, Son et al.6 focused on the moist and open condition without compression and reported a 65% survival rate, which was slightly higher than the survival rate in this study. The study discussed the association of composite graft survival rate with the moist condition of the stump, but it did not mention the use of postoperative ice cooling or PGE1 injection. Direct comparison between that study and the present was not easy because patient selection might have been biased, the categorization of injury level was different, and the hospital or operative condition might be different.

In this study, 25 of 41 composite grafts (61.0%) showed complete survival at 8 weeks after surgery, under the condition of postoperative management of graft ice cooling combined with intravenous PGE1 injection and moist open dressing. The present study reported comparable results in cases with low injury level and guillotine injury. In cases with type I injury level, survival rate was 82.4% (14/17), whereas the success rates were 60.0% (6/10) and 35.7% (5/14) in type II and III injuries, respectively (p<0.05). Regarding injury mode, cases with guillotine injury showed a survival rate of 85.7% (18/21); however, the survival rate of crushing injuries was 35.0% (7/20) (p<0.05). Other studies also had high survival rates. The study by Eo et al.4, in which the postoperative wound care method was slightly modified by applying ice cooling, PGE1 administration, proximal compression moist dressing with elastic tape, also had a favorable survival rate (89.3%). Hirase3 was the first to use PGE1 for engraftment after 3 days of ice cooling and reported a final survival rate of 81.0%. Son et al.6 had 65.0% complete engraftment without any further procedure.

The present study also investigated the clinical parameters associated with composite graft survival in patients with fingertip injury. Female sex, low level of injury, guillotine injury mode, and cold temperature were correlated with higher graft survival rate. However, in the multivariate analysis, injury level difference between types I and III, injury mode, and outdoor temperature were the three independent clinical parameters associated with composite graft survival. The female sex showed significantly higher survival rate; however, the multivariate study revealed that the higher survival rate in females may have inaccurately resulted from the non-exclusion of the association between sex and other independent variables (level of injury, injury mode, etc.). The main injury mode in males was due to grinders, hammers, or conveyer belts, which were crushing injuries. On the contrary, most fingertip injuries in females were due to guillotine injury, and most occurred while they were cooking, and a kitchen knife can scarcely harm the bone beyond the soft tissue or crush the tissue severely. This might may have resulted in the pseudo-higher survival rate in females.

In literatures, several authors presented many variables affecting composite graft success in the fingertips. The injury type, injury level, and duration of ischemic time before graft were reported to influence engraftment414. Eo et al.4 indicated that the delay in time from injury to operation was significantly shorter in the survival group than in the failure group. Heistein and Cook14 reported that smoking was the only significant factor that had a strong and independent association with composite graft loss. Furthermore, according to Eo et al.4, failure of the composite graft was independently associated with a crushing injury.

For possible explanation for the effect of injury level difference between types I and III, we believe that in injuries with larger volume of stump tissue, the circulation through the contact surface was not enough to nourish the stump tissue until new vessels grow. The mode of injury was also an independent factor for survival rate. Crushing injury includes soft tissue injury around the wound site as well as destruction of the vasculature. This vascular insufficiency lowers the circulation to the stump after composite grafting. Furthermore, the contact surface is irregular in crushing injury compared with that of lacerated injury, which usually has an even surface, implying that the total contact surface would not fit to each other. Thus, these possibly explain the difficult survival in crushing injury. The outdoor temperature was evaluated as a baseline investigation of circumstances; however, unexpectedly, the cold temperature was statistically helpful for graft survival1516. Low temperature reduces the degeneration of amputated tissue, and it is assumed that the outdoor temperature affected the tissue temperature when the stump has been exposed to the external atmosphere during the referral7. Public advertising of immediate cooling of the amputee after an accident occurs could be beneficial to graft survival.

This study has some limitations. Because of the nature of the retrospective design, our present study could not quantify the effect of ice bag cooling accurately. Further large prospective study with control group would be helpful to elucidate the limitation of the present study and to set a new protocol of postoperative ice bag cooling after composite grafting. Another drawback is that as we strongly prohibited smoking during the hospitalization and recovery period; hence, the effect of smoking on survival could have been neglected in this study. Based on the report of Heistein and Cook14 that smoking was the only independent factor with composite graft failure, smoking as a risk factor of surgical failure should be verified in other studies with large sample size. Lastly, the patients in this study were not able to undergo hyperbaric oxygen therapy because the hospital did not have a hyperbaric chamber. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is known to improve the survival of hypoperfused tissue17. The increased pressure of oxygen can compensate for the decreased oxygen supply with normal pressure during the early postoperative period. Future study with hyperbaric chamber facility should be conducted.

Meanwhile, the study has its strengths. This study showed successful outcomes with postoperative ice bag cooling combined with PGE1 injection and moist open dressing and addressed the variety of factors that might affect survival rate. Future prospective study with control group of ice bag cooling postoperative care and survival rate may reveal more specific association. Furthermore, as the associated risk factors revealed in this study were noncontrollable, investigating reliable controllable factors for graft survival should be conducted.

The present study reported comparable results with postoperative ice bagging. The other two postoperative methods, PGE1 injection and moist open dressing, are now widely used. Postoperative management (i.e., changing the milieu) is a controllable factor to enhance the survival rate. A standard combination of postoperative management is needed.

This study revealed favorable surgical outcomes, especially in cases with low injury level (type I, 82.3%) and guillotine injury (77.8%). The multivariate analysis revealed that injury level difference between types I and III, injury mode, and outdoor temperature were the three independent clinical parameters associated with composite graft survival. However, these factors are uncontrollable. Conducting prospective study on milieu factors such as ice cooling or moist open dressing is necessary to save amputated stump and to set a new protocol of postoperative management after composite grafting.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Open moist dressing: (A) dorsal view, (B) palmar view, (C) fingertip view, and (D) fingertip view with ointment. |

| Fig. 2Level I injury caused by crushing trauma on the right thumb of a 45-year-old male patient: (A) day of trauma day, (B) immediately postoperative, (C) postoperative day 2, and (D) postoperative day 31. The thumb showed complete survival. |

| Fig. 3Level II injury caused by guillotine injury on the left third and fourth fingers of a 56-year-old male patient: (A) day of trauma, (B) immediately postoperative, (C) postoperative day 13, (D) postoperative week 8 (anteroposterior view), and (E) postoperative week 8 (fingertip view). The third finger showed complete survival, whereas the fourth finger had partial failure. |

References

1. Komatsu S, Tamai S. Successful replantation of a completely cut-off thumb. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968; 42:374–377.

2. Elliot D, Moiemen NS. Composite graft replacement of digital tips. 1. Before 1850 and after 1950. J Hand Surg Br. 1997; 22:341–345.

3. Hirase Y. Salvage of fingertip amputated at nail level: new surgical principles and treatments. Ann Plast Surg. 1997; 38:151–157.

4. Eo S, Doh G, Lim S, Hong KY. Analysis of the risk factors that determine composite graft survival for fingertip amputation. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2018; 43:1030–1035.

5. Eo S, Hur G, Cho S, Azari KK. Successful composite graft for fingertip amputations using ice-cooling and lipo-prostaglandin E1. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009; 62:764–770.

6. Son D, Chu H, Yeo H, Kim JH, Han K. Finger tip composite grafting managed with moist-exposed dressing. J Korean Soc Surg Hand. 2012; 17:9–15.

7. Conley JJ, Vonfraenkel PH. The principle of cooling as applied to the composite graft in the nose. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946). 1956; 17:444–451.

10. Kiuchi T, Shimizu Y, Nagasao T, Ohnishi F, Minabe T, Kishi K. Composite grafting for distal digital amputation with respect to injury type and amputation level. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2015; 49:224–228.

11. Bergamini CM, Gambetti S, Dondi A, Cervellati C. Oxygen, reactive oxygen species and tissue damage. Curr Pharm Des. 2004; 10:1611–1626.

12. Son D, Han K, Chang DW. Extending the limits of fingertip composite grafting with moist-exposed dressing. Int Wound J. 2005; 2:315–321.

13. Svensjö T, Pomahac B, Yao F, Slama J, Eriksson E. Accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds in a wet environment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:602–612. discussion 613–4.

14. Heistein JB, Cook PA. Factors affecting composite graft survival in digital tip amputations. Ann Plast Surg. 2003; 50:299–303.

15. Choo J, Sparks B, Kasdan M, Wilhelmi B. Composite grafting of a distal thumb amputation: a case report and review of literature. Eplasty. 2015; 15:e5.

16. Idone F, Sisti A, Tassinari J, Nisi G. Cooling composite graft for distal finger amputation: a reliable alternative to microsurgery implantation. In Vivo. 2016; 30:501–505.

17. McFarlane RM, Wermuth RE. The use of hyperbaric oxygen to prevent necrosis in experimental pedicle flaps and composite skin grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966; 37:422–430.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download