Abstract

Purpose

As prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide, finding novel markers for prognosis is crucial. BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP-1), a nuclear-localized deubiquitinating enzyme, has been reported in several human cancers. However, its prognostic role in PCa remains unknown. Herein, we assessed the prognostic and clinicopathologic significance of BAP-1 in PCa.

Materials and Methods

Seventy surgical specimens from radical prostatectomy cases were examined. Two cores per case were selected for construction of tissue microarrays (TMAs). After the exclusion of two cases because of tissue sparsity, BAP-1 immunohistochemical expression was evaluated in 68 cases of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded TMA tissue blocks. The immunohistochemical stain was scored according to proportion of nuclear staining: negative (<10% of tumor cells) or positive (≥10% of tumor cells).

Results

BAP-1 expression was negative in 30 cases (44.1%) and positive in 38 cases (55.9%). Positive BAP-1 expression was more common in pT3b disease than in pT2 (p=0.038). A high preoperative prostate-specific antigen level was correlated with BAP-1 expression (p=0.014). Age, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and grade group were not significantly correlated with BAP-1 expression. Patients with positive BAP-1 expression showed significantly shorter disease-free survival (p=0.013). Additionally, BAP-1 was an independent prognostic factor of PCa (p=0.035; hazard ratio, 9.277; 95% confidence interval, 1.165–73.892).

Prostate cancer (PCa) is diagnosed in 13.5% of male cancer patients worldwide, making it the second most frequently diagnosed cancer in men [1]. PCa usually appears in a localized form, but clinical outcomes vary considerably. Current clinical prognostic factors are very limited in their ability to improve individual triaging of patients to refine prognosis or recurrent risk. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate PCa progression factors and to find novel biomarkers for predicting PCa prognosis.

BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP-1), a deubiquitinating protein [2], regulates cell cycles and DNA damage by interacting with the BRCA1/BARD1 tumor-suppressor heterodimer [3]. Also, nuclear-localized BAP-1 functions as an independent inhibitor in cell proliferation and as a regulator of apoptosis [4]. In addition to these growth inhibitory functions, BAP-1 also acts as an activator of cell proliferation. By forming complexes with host cell factor 1 (HCF-1) and through deubiquitination, BAP-1 acts as a cell cycle progression factor at the G1/S transition [5]. Depletion of BAP-1 has even been shown to slow the S phase [3]. Thus, BAP-1 plays dual roles in cell cycle regulation as an activator and deactivator [6].

In recent years, a BAP-1 loss-of-function mutation has been described for several cancers. According to earlier reports, a germline BAP-1 mutation is associated with several hereditary cancer syndromes, including uveal melanoma, malignant pleural mesothelioma, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, and cholangiocarcinoma [78910]. Additional studies identified somatic BAP-1 mutations that were also associated with corresponding cases [111213]. However, the view of BAP-1 as a prognostic biomarker is controversial. Patients with BAP-1 loss-of-function mutations have shorter overall survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and uveal melanoma [14]. In contrast, malignant pleural mesothelioma patients with high BAP-1 expression have shorter overall survival [15]. Thus, the prognostic role of BAP-1 depends on cancer type.

A previous study showed that immunohistochemical staining for BAP-1 protein was a good surrogate marker for locating BAP-1 mutations [16]. Thus, BAP-1 protein analysis by immunohistochemistry (IHC) might be useful for prognostic evaluation during routine work-up. Here, we evaluated BAP-1 expression in PCa and estimated the correlations between BAP-1 and clinicopathologic parameters, as well as disease-free survival.

From January 2009 to November 2013, surgical specimens from patients diagnosed with prostate adenocarcinoma who underwent radical prostatectomy at Korea University Anam Hospital were examined. Patients who had other primary malignancy were excluded. Finally, 70 cases were chosen. None of the patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Patients' clinicopathologic features, including age at diagnosis, preoperative prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, metastasis status, pathologic T-stage, and disease-free survival, were retrospectively obtained. One pathologist (YJL) reevaluated the tumors and classified them according to recently updated Gleason score and grade group [17]. Pathologic T-stage was modified according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition, in which all organ-confined PCa cases were assigned as pT2 without subclassification [18]. The cutoff point for biochemical recurrence was persistent PSA >0.2 ng/mL [19]. The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University College of Medicine (approval number: 2019AN0125).

Two cores were obtained from each formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded prostate adenocarcinoma tissue block. The 3-mm-diameter PCa tissue cores were transferred and embedded into a tissue microarray (TMA) block. There were two selection criteria for cores: 1) an area with the highest Gleason score and 2) an area with sufficient tumor extent that was larger than 3 mm in diameter.

The BAP-1 antibody (clone C-4, 1:50 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was used for IHC staining. Sections 4-µm thick from the TMA tissue blocks were stained by use of an automated staining facility (Leica BOND-MAX; Leica Microsystems, Melbourne, Australia). Normal pancreatic tissue and malignant mesothelioma sections were used as positive and negative controls, respectively, for BAP-1 immunostaining.

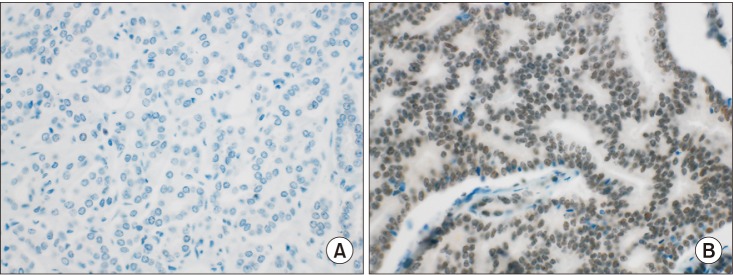

IHC staining for BAP-1 was interpreted according to the proportion of stained cells. Only nuclear staining was considered, and cytoplasmic staining was regarded as negative. The proportion was scored based on the average staining proportion of the two cores. BAP-1 staining was considered positive if any intensity of nuclear staining was noted in ≥10% of tumor cells and negative if staining was noted in <10% of tumor cells (Fig. 1). The cutoff value was set according to the criteria defined previously by Shah et al. [20].

All statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The correlation between BAP-1 expression and clinicopathologic features of prostate adenocarcinoma were calculated using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. Disease-free survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the significance of the difference between BAP-1 expression was analyzed using the log-rank test. Each clinical factor was evaluated for independent prognostic significance using the Cox proportional-hazards regression model, and factors yielding a p-value <0.05 in univariate analyses were included in the multivariate model. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sixty-eight of 70 cases were analyzed for this study. Two cases were excluded because they lacked tumor cells in the TMA. Patient age ranged from 49 to 76 years, with a mean age of 63 years. PSA level ranged from 3.34 to 45.91 ng/mL, with a mean of 11.36 ng/mL. There were 17, 45, 4, and 2 cases with Gleason scores of 6, 7, 8, and 9, respectively. There were 17, 36, 9, 4, and 2 cases in grade group 1 (Gleason score ≤6), group 2 (Gleason score 3+4), group 3 (Gleason score 4+3), group 4 (Gleason score 8), and group 5 (Gleason score 9 or 10), respectively. Lymphovascular invasion was present in 4 cases, and perineural invasion was present in 35 cases. Among the 68 cases, 47, 10, and 11 cases were stage pT2, pT3a, and pT3b, respectively. All cases were of localized PCa without metastasis at the time of diagnosis. The median follow-up time was 92 months (range, 2–120 months).

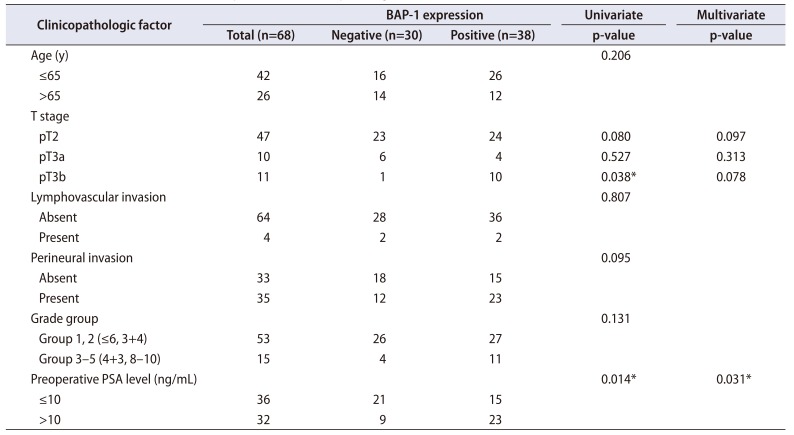

Of the 68 cases, BAP-1 expression was negative in 30 (44.1%) and positive in 38 (55.9%). BAP-1-positive PCa was significantly correlated with higher preoperative PSA level by univariate logistic regression analysis (p=0.014; odd ratio, 3.578). BAP-1 expression was more common in pT3b disease than in pT2 (p=0.038; odd ratio, 9.583). Age, grade group, lymphovascular invasion, and perineural invasion showed no significant correlation with BAP-1 expression. By multivariate logistic regression analysis, preoperative PSA level was significantly correlated with BAP-1 expression (p=0.031; odd ratio, 3.350; Table 1).

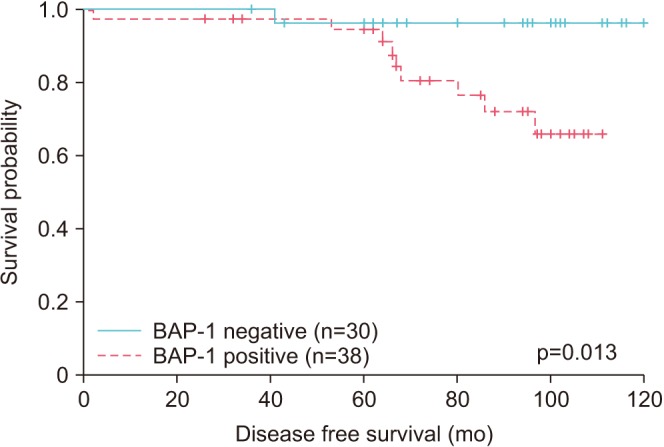

Ten of the 68 total cases experienced biochemical recurrence: 1 had negative BAP-1 expression, and the other 9 cases had positive BAP-1 expression. Because survival was greater than 50% at the last time point, median survival was undefined. The 86-month survival percentages of BAP-1-negative and BAP-1-positive cases were 96.6% and 72%, respectively. Patients with positive BAP-1 expression had significantly shorter disease-free survival (p=0.013; Fig. 2). There was no cancer-related death in the 68 cases.

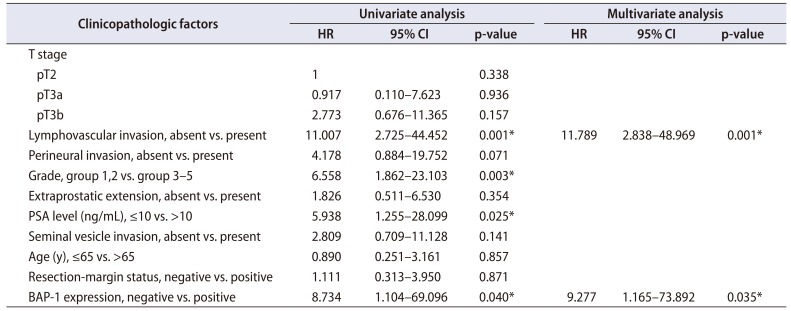

Univariate survival analysis via the Cox proportionalhazards regression model showed that BAP-1 expression was related to shorter disease-free survival (p=0.040). Preoperative PSA level (>10 ng/mL), higher grade group, and lymphovascular invasion were significantly associated with shorter disease-free survival (p=0.025, 0.003, and 0.001, respectively). T-stage, perineural invasion, resection-margin status, and age were not significantly correlated with disease-free survival. In the multivariate survival analysis including preoperative PSA level, grade group, and lymphovascular invasion by back variable selection using the Wald method, BAP-1 expression and lymphovascular invasion were final independent variables that were significantly correlated with disease-free survival (p=0.035 and 0.001, respectively; Table 2).

Ubiquitin attaches to proteins and causes post-translational modification that either alters target protein function or suppresses protein expression. Deubiquitinase removes ubiquitin via hydrolysis. Depending on its target, the function of deubiquitinase on cellular regulation could differ. When tumor suppressors are deubiquitinated, their expression is preserved, preventing uncontrolled cellular proliferation. In this case, deubiquitinase acts as a tumor suppressor. Overall, the role of BAP-1, a nuclear-localized deubiquitinating protein [2], could differ according to target protein.

Earlier studies reported that BAP-1 binds to the RING finger motif of BRCA1 and enhances the BRCA1-mediated cellular growth suppressor function by deubiquitination [2]. By serving as a regulator of the BRCA1 pathway, BAP-1 acts as a tumor suppressor.

However, several other studies reported that BAP-1 participates in cell proliferation. BAP-1 depletion by RNAi inhibits proliferation of breast cancer cells (MCF-7 and T-47D). Furthermore, previous research argued that the interaction between BAP-1 and HCF-1 is critical for BAP-1-mediated cell growth. HCF-1, a cell cycle modulator, is a heterodimer composed of HCF-1N and HCF-1C. In particular, BAP-1 regulates cell proliferation by deubiquitinating HCF-1N, which promotes G1-phase progression and S-phase entry [321]. Another study revealed that BAP-1 loss downregulates the downstream targets of E2F, an important cell cycle progression factor, including cyclin A2, E2F1, p107, and CDC25C [11]. Taken together, these findings indicate that BAP-1 may play a dual role in cellular growth, both preventing excessive growth and ensuring appropriate cell growth.

BAP-1 status can be evaluated by three methods. First, genomic hybridization can inspect for deletions in the BAP-1 gene locus at 3p21. Second, the BAP-1 gene can be sequenced to identify any mutations. Third, IHC can detect BAP-1 proteins [20]. Evaluating BAP-1 protein expression via IHC is considered the superior method for evaluating BAP-1's functional status, rather than evaluating deletions or mutations in coding lesions [16]. Moreover, because most BAP-1 mutations cause rapid degradation of proteins or reduce nuclear localization, BAP-1 mutations are highly associated with negative immunohistochemical staining [22].

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide evidence of correlations between BAP-1 expression and clinicopathologic factors in PCa cases using IHC. In our study, PCa cases with positive BAP-1 expression had significantly higher T-stage and higher PSA level. Consistently, PCa patients with positive BAP-1 expression had shorter disease-free survival than did patients with negative BAP-1 expression. Also, high preoperative PSA level, high grade group, and lymphovascular invasion were significantly associated with shorter disease-free survival. However, a preexisting staging score, including T-stage, extraprostatic extension, and seminal vesicle invasion, were not correlated with disease-free survival. This result could be explained by the relatively small number of cases. Despite our limited sample size, our study adds to the literature suggesting BAP-1 immunoexpression as a potential prognostic biomarker.

Although BAP-1 has been discussed in a broad spectrum of cancers, consensus has not been reached for it prognostic role. BAP-1 loss is associated with poor prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and uveal melanoma [14]. In contrast, however, BAP-1 loss was found to have a protective role in malignant mesothelioma, which is consistent with our results for PCa [15]. These conflicting results support the view that BAP-1 may have many yet unknown biological functions, and that its activity might have a tissue-specific pattern. Especially in PCa cases, the BAP-1 gene may play an oncogenic role rather than a generally well-known tumor-suppressor role.

Since BAP-1 functions as a deubiquitinating enzyme, it can act as either an oncogene or a tumor-suppressor gene, depending on the target protein for deubiquitination. As previously mentioned, cell cycle proliferation pathways such as the HCF-1 molecular pathway and E2F related proteins would be affected by BAP-1 oncogenic action [311]. Other molecular pathways associated with BAP-1 need to be clarified in further studies.

BAP-1 was initially discovered as a BRCA1-associated protein [2], and many studies are now attempting to identify the association between BAP-1 and BRCA1, especially the pathways associated with histone H2A, heterochromatin, and DNA damage response [23]. A study by Omari et al. [24] reported that BRCA1 gene loss along with BRCA1 gene gain is associated with ALDH1 expression, which is a stem cell marker. This indicates that BRCA1 gene gain is associated with PCa dedifferentiation. The poor prognosis among patients with positive BAP-1 expression might be explained by BRCA1 gene gain affecting dedifferentiation. Also, the cooperative activity between BRCA1 and BAP-1 could be a future drug target.

Our study limitations included our relatively small cohort study size and the lack of genomic or mutational testing in our analyses. Despite these limitations, ours is the first study to correlate BAP-1 immunoexpression with clinicopathologic factors in PCa, and we revealed that BAP-1 is a potential prognostic marker for PCa. Larger-scaled and molecular studies will further enhance the validity of our research, and they could also serve to elucidate new therapeutic strategies. Finally, IHC for BAP-1 may be used for preoperative biopsy specimens for PCa treatment planning.

The purpose of our study was to determine whether BAP-1 IHC can stratify PCa prognoses in a clinically useful way. In our dataset, BAP-1 immunoexpression predicted poor prognosis in PCa patients. Analyzing BAP-1 expression by IHC may be a valuable way to stratify more aggressive PCa cases from less aggressive cases. The precise role of BAP-1 in PCa deserves further investigation and validation in future studies.

Notes

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS:

Research conception and design: Yoo Jin Lee and Yang-Seok Chae.

Data acquisition: Sung Gu Kang, Bokyung Ahn, and Eojin Kim.

Statistical analysis: Harim Oh and Youngseok Lee.

Data analysis and interpretation: Harim Oh, Yoo Jin Lee, Jeong Hyeon Lee, and Chul Hwan Kim.

Drafting of the manuscript: Harim Oh.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Chul Hwan Kim.

Supervision: Chul Hwan Kim.

Approval of the final manuscript: Chul Hwan Kim.

References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018; 68:394–424. PMID: 30207593.

2. Jensen DE, Proctor M, Marquis ST, Gardner HP, Ha SI, Chodosh LA, et al. BAP1: a novel ubiquitin hydrolase which binds to the BRCA1 RING finger and enhances BRCA1-mediated cell growth suppression. Oncogene. 1998; 16:1097–1112. PMID: 9528852.

3. Nishikawa H, Wu W, Koike A, Kojima R, Gomi H, Fukuda M, et al. BRCA1-associated protein 1 interferes with BRCA1/BARD1 RING heterodimer activity. Cancer Res. 2009; 69:111–119. PMID: 19117993.

4. Ventii KH, Devi NS, Friedrich KL, Chernova TA, Tighiouart M, Van Meir EG, et al. BRCA1-associated protein-1 is a tumor suppressor that requires deubiquitinating activity and nuclear localization. Cancer Res. 2008; 68:6953–6962. PMID: 18757409.

5. Machida YJ, Machida Y, Vashisht AA, Wohlschlegel JA, Dutta A. The deubiquitinating enzyme BAP1 regulates cell growth via interaction with HCF-1. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284:34179–34188. PMID: 19815555.

6. Rai K, Pilarski R, Cebulla CM, Abdel-Rahman MH. Comprehensive review of BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome with report of two new cases. Clin Genet. 2016; 89:285–294. PMID: 26096145.

7. Testa JR, Cheung M, Pei J, Below JE, Tan Y, Sementino E, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant esothelioma. Nat Genet. 2011; 43:1022–1025. PMID: 21874000.

8. Popova T, Hebert L, Jacquemin V, Gad S, Caux-Moncoutier V, Dubois-d'Enghien C, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to renal cell carcinomas. Am J Hum Genet. 2013; 92:974–980. PMID: 23684012.

9. Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Murali R, Fried I, Griewank KG, Ulz P, et al. Germline mutations in BAP1 predispose to melanocytic tumors. Nat Genet. 2011; 43:1018–1021. PMID: 21874003.

10. Klebe S, Driml J, Nasu M, Pastorino S, Zangiabadi A, Henderson D, et al. BAP1 hereditary cancer predisposition syndrome: a case report and review of literature. Biomark Res. 2015; 3:14. PMID: 26140217.

11. Bott M, Brevet M, Taylor BS, Shimizu S, Ito T, Wang L, et al. The nuclear deubiquitinase BAP1 is commonly inactivated by somatic mutations and 3p21.1 losses in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nat Genet. 2011; 43:668–672. PMID: 21642991.

12. Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, Duan S, Cao L, Worley LA, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010; 330:1410–1413. PMID: 21051595.

13. Peña-Llopis S, Vega-Rubín-de-Celis S, Liao A, Leng N, Pavía-Jiménez A, Wang S, et al. BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012; 44:751–759. PMID: 22683710.

14. Wang XY, Wang Z, Huang JB, Ren XD, Ye D, Zhu WW, et al. Tissue-specific significance of BAP1 gene mutation in prognostic prediction and molecular taxonomy among different types of cancer. Tumour Biol. 2017; 39:1010428317699111. PMID: 28618948.

15. Arzt L, Quehenberger F, Halbwedl I, Mairinger T, Popper HH. BAP1 protein is a progression factor in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014; 20:145–151. PMID: 23963927.

16. Wiesner T, Murali R, Fried I, Cerroni L, Busam K, Kutzner H, et al. A distinct subset of atypical Spitz tumors is characterized by BRAF mutation and loss of BAP1 expression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012; 36:818–830. PMID: 22367297.

17. Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, Delahunt B, Srigley JR, Humphrey PA. Grading Committee. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016; 40:244–252. PMID: 26492179.

18. Amin MB. American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer;2017.

19. Freedland SJ, Sutter ME, Dorey F, Aronson WJ. Defining the ideal cutpoint for determining PSA recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Prostate-specific antigen. Urology. 2003; 61:365–369. PMID: 12597949.

20. Shah AA, Bourne TD, Murali R. BAP1 protein loss by immunohistochemistry: a potentially useful tool for prognostic prediction in patients with uveal melanoma. Pathology. 2013; 45:651–656. PMID: 24247622.

21. Julien E, Herr W. Proteolytic processing is necessary to separate and ensure proper cell growth and cytokinesis functions of HCF-1. EMBO J. 2003; 22:2360–2369. PMID: 12743030.

22. Luchini C, Veronese N, Yachida S, Cheng L, Nottegar A, Stubbs B, et al. Different prognostic roles of tumor suppressor gene BAP1 in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016; 55:741–749. PMID: 27223342.

23. Fukuda T, Tsuruga T, Kuroda T, Nishikawa H, Ohta T. Functional link between BRCA1 and BAP1 through histone H2A, heterochromatin and DNA damage response. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2016; 16:101–109. PMID: 26517537.

Fig. 1

Immunohistochemical staining for BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP-1): (A) BAP-1 negative, (B) BAP-1 positive (all cases 400×).

Fig. 2

Kaplan–Meier curves showing association of disease-free survival with BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP-1) expression.

Table 1

The correlation between BAP-1 expression and clinicopathologic factors

Table 2

Cox proportional hazard regression model survival analysis

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download