Abstract

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma (PHL) is a rare malignant tumor, which originates from smooth muscles. Clinical presentation and imaging features are non-specific and can mimick the most frequent primary liver tumors namely hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. We report here two cases of PHL including one from the portal vein. The literature was searched for studies reporting cases of PHL reported from 2011 and 2019. The two patients were operated with R0 resection. Diagnosis of PHL was confirmed by histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations. Surgery remains the mainstay of the management of PHL. R0 resection is the main prognostic factor. Our literature search identified 16 additional cases from 12 reports. Preoperative diagnosis of PHL needs a high degree of suspicion due to atypical clinical presentation and non-specific imaging features. Surgery is the mainstay of the management of PHL. R0 resection is the main prognostic factor.

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcomas (PHL) include 6–16% of the primary hepatic sarcomas which in turn represent 0.2–2% of primary hepatic cancers.1 Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma (PHL) is a rare malignant tumor, which originates from smooth muscles. Clinical presentation and imaging features are non-specific and can mimick the most frequent primary liver tumors namely hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. This tumor has aggressive metastatic potential and is usually diagnosed in a locally advanced or metastatic disease. Radical R0 hepatectomy remains the only curative treatment of PHL, but the large majority of unoperated patients had technically non-resectable disease and/or extra-hepatic metastases. We report here two cases of PHL including one arising from the portal vein to update the nosology, incidence, diagnosis and management of this rare disease. The cases reported here comply with the CARE guidelines checklist for case reports.2

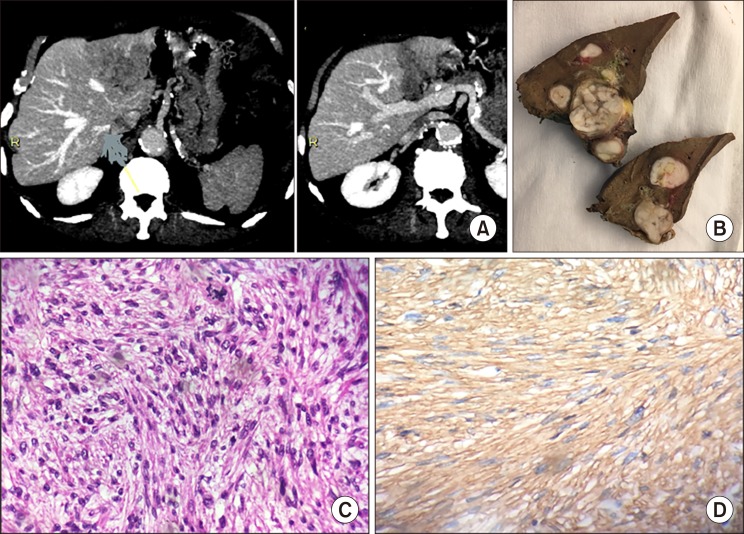

A left liver mass was incidentally discovered during cardiac ultrasonography in an asymptomatic 78-year old male patient. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a large tumor (57 mm in diameter), well defined, heterogeneous and spontaneously hypodense (Fig. 1A). Contrast imaging showed mild and mostly peripheral wash-in and no wash-out. The whole left portal vein system was enlarged by a tumor thrombus (TT) enhanced on arterial phase. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the tumor was heterogeneous and hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images without encapsulation. At arterial and portal phase, the TT was discretely hypervascular. The non-tumor liver parenchyma was normal on cross imaging. Thorax and pelvis imaging as well as upper gastrointestinal and recto-colonoscopy were normal. Screening for viruses B, and C was negative, and the following laboratory parameters including complete peripheral blood cell count, kidney and liver function tests, and tumor markers (CEA, CA 19-9, AFP) were within normal limits. Liver tumor board concluded to the diagnosis of probable hepatocellular carcinoma with left portal vein TT developed on healthy liver and advised upfront surgery. At laparoscopy, there was no ascites and no suspect lymph node in the liver pedicle. Intraoperative ultrasonography confirmed the tumor characteristics and ruled out additional intra-hepatic lesions. A laparoscopic left hepatectomy was performed. Post-operative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged home nine days after surgery. Specimen analysis confirmed the resection was R0 and the healthy non-tumor parenchyma. The tumor was composed of atypical spindle cells with a fascicular growth pattern. The proliferation index was estimated at 10% of tumor cells. Immunohistochemical staining against α-smooth muscle actin was strongly positive (Fig. 1B–D). The liver tumor board decided no adjuvant treatment. Eighteen months after surgery, the patient was well without recurrence. The tumor was grade 2 according to the FNCLCC (Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer).3

A sensible right hepatomegaly was discovered in a 53 year-old man complaining of abdominal pain. CT scan showed right liver tumor (29 cm in diameter) with compressed but patent portal and hepatic veins. Contrast imaging showed peripheral enhancement at late arterial phase. At MRI, the tumor was hyperintense and hypointense on T2-weighted and T1-weighted images, respectively. Peripheral contrast uptake was seen at arterial phase followed by reinforcement at the portal phase. The right portal vein could not be identified (Fig. 2A, B). Thoracic CT showed 2 infra-centimetric non-specific pulmonary nodules. Percutaneous tumor biopsy at the referring center concluded to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Upper and lower gastro- intestinal endoscopies as well as liver and kidney function tests, and tumor markers (CEA, CA 19-9, AFP) were normal. Screening for viruses B, C, and HIV was negative. The decision was to perform upfront liver resection with the diagnosis of massive symptomatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. At laparotomy, there was neither suspicious lymph node nor extrahepatic lesion. Right extended hepatectomy under total vascular exclusion of the liver with hypothermic portal perfusion and veno-venous bypass was performed4 together with lymph node dissection of the liver pedicle. Postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged home 24 days following surgery. The specimen weighed 5300 g and contained more than 1 L of hemorrhagic liquid (Fig. 2C, D). No tumor invasion was found in 5 lymph nodes, and the non-tumor liver parenchyma was normal. The tumor was not encapsulated, and no vascular invasion was found. Immuno-histochemistry showed homogenous and diffuse staining for smooth muscle markers i.e., α-smooth muscle actin, h-Caldesmone, and desmin. In addition, the tumor was negative for CD 34, cytokeratin CKAE1/AE3, C-Kit/CD117, PS100, hepatocyte antigen, and Glypican-3. The proliferation index was estimated at 30% of tumor cells. The tumor was graded FNCLCC grade 3. Multiple lungs metastases were diagnosed 7 months following surgery. In accordance with the patient, only best supportive care was given, and the patient died with terminal diffuse disease 14 months following surgery.

A systematic review of the literature by Chi et al.5 already identified 109 cases of PHL reported from 1900 to March 2011. To update the latter, our search used the same searching data bases and MeSH terms applied to the period April 2011-April 2019. Reference lists of related articles and review articles were manually screened for additional citations. Our literature search identified 16 additional cases from 12 reports.67891011121314151617 One registry was not included to obviate redundancy.18

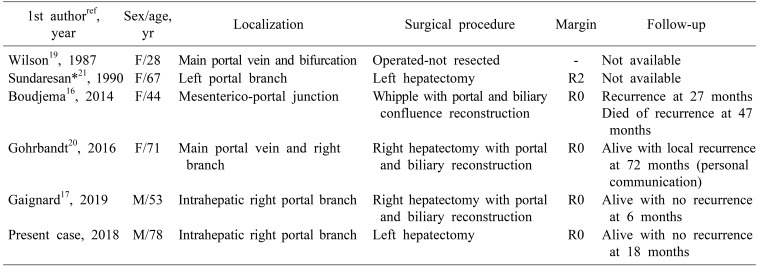

Originating from smooth muscle, PHLs can arise from intrahepatic vascular structures, bile ducts or the round ligament.6 The presence of a portal vein TT in our first case claims for a portal vein origin of the tumor. Among vascular leiomyosarcomas, those arising from portal vein are very rare and only five cases have been reported.1617192021 These cases are summarized in Table 1. R0 resection could be performed in 4 out of 5 evaluable patients. Logically, hepatocellular carcinoma developed in healthy liver with portal vein TT is the first differential diagnosis for this type of PHL. Our first case was treated as so.25 The following indirect arguments claim for a biliary origin of the second case: the round ligament and the vessels of the specimen were tumor free.

Diagnostic of PHL needs a high level of suspicion because clinical scenario,6 and cross-imaging1123 are not specific. Further, the absence of serological markers often delays diagnosis at the stage of large and/or metastatic tumor.5 Concordant with our cases, hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma are the main differential diagnoses. Indeed, tumor biopsy is the only mean to achieve formal diagnosis of PHL. Intentionally, preoperative tumor biopsy was not performed in our first case because i) cross imaging strongly suggested hepatocellular carcinoma, ii) upfront surgery was indicated for obviously malignant tumor independently of a specific tumor diagnosis, iii) the risks of tumor biopsy (of severe bleeding=0.6% to 1.7%,2425 of tumor seeding for hepatocellular carcinoma= 2.7%26) was not balanced by the potential benefit of any neoadjuvant treatment. Nevertheless, we acknowledge preoperative biopsy should be considered on a case-by-case basis. Immunohistochemistry easily makes the right diagnostic and staging.3 This was not performed at the referral center in our second case and explains the wrong initial diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma.

Radical R0 hepatectomy is the cornerstone of successful management of PHL. Considering the present update of the systematic review by Chi et al.,5 111 cases could be analyzed for treatment of which 71 could be operated (64%). The vast majority of unoperated patients had technically non-resectable disease and/or extra-hepatic metastases. In terms of survival, Chi et al.5 could analyze 84 cases. A median overall survival of 19 months (range 0–181 months) with 1-, 2-, and 5-year survival rates of 61.2%, 41.1%, and 14.5%, respectively was found. Smaller size of lesion and more importantly tumor-free resection margin were identified as independent predictors of improved survival. Specific survival following R0 surgery was not reported. The role of chemotherapy (either for neoadjuvant, adjuvant or for palliative purposes) for PHL, as for leiomyosarcomas in general, is unclear. The role of liver transplantation remains controversial.

In conclusion, leiomyosarcomas of the liver are rarely primitive and preoperative diagnosis needs a high degree of suspicion due to atypical clinical presentation and non-specific imaging features. Surgery is the mainstay of the management of PHL. R0 resection is the main prognostic factor. The place of perioperative chemotherapy remains debated.

References

1. Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Primary liver cancer in Japan. Clinicopathologic features and results of surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1990; 211:277–287. PMID: 2155591.

2. Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley D. CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014; 67:46–51. PMID: 24035173.

3. Coindre JM. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: review and update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006; 130:1448–1453. PMID: 17090186.

4. Azoulay D, Lim C, Salloum C, Andreani P, Maggi U, Bartelmaos T, et al. Complex liver resection using standard total vascular exclusion, venovenous bypass, and in situ hypothermic portal perfusion: an audit of 77 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2015; 262:93–104. PMID: 24950284.

5. Chi M, Dudek AZ, Wind KP. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in adults: analysis of prognostic factors. Onkologie. 2012; 35:210–214. PMID: 22488093.

6. Shivathirthan N, Kita J, Iso Y, Hachiya H, Kyunghwa P, Sawada T, et al. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011; 3:148–152. PMID: 22046492.

7. Takehara K, Aoki H, Takehara Y, Yamasaki R, Tanakaya K, Takeuchi H. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma with liver metastasis of rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012; 18:5479–5484. PMID: 23082067.

8. Chelimilla H, Badipatla K, Ihimoyan A, Niazi M. A rare occurrence of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma associated with epstein barr virus infection in an AIDS patient. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013; 2013:691862. PMID: 24024048.

9. Majumder S, Dedania B, Rezaizadeh H, Joyal T, Einstein M. Tumor rupture as the initial manifestation of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2014; 7:33–34. PMID: 24558513.

10. Lin YH, Lin CC, Concejero AM, Yong CC, Kuo FY, Wang CC. Surgical experience of adult primary hepatic sarcomas. World J Surg Oncol. 2015; 13:87. PMID: 25880743.

11. Lv WF, Han JK, Cheng DL, Tang WJ, Lu D. Imaging features of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: a case report and review of literature. Oncol Lett. 2015; 9:2256–2260. PMID: 26137052.

12. Hamed MO, Roberts KJ, Merchant W, Lodge JP. Contemporary management and classification of hepatic leiomyosarcoma. HPB (Oxford). 2015; 17:362–367. PMID: 25418451.

13. Iida T, Maeda T, Amari Y, Yurugi T, Tsukamoto Y, Nakajima F. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. CEN Case Rep. 2017; 6:74–78. PMID: 28509136.

14. Giakoustidis D, Giakoustidis A, Goulopoulos T, Arabatzi N, Kainantidis A, Zaraboukas T. Primary gigantic leiomyosarcoma of the liver treated with portal vein embolization and liver resection. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2017; 21:228–231. PMID: 29264587.

15. Zhou F, Huang HZ, Zhou MT, Han SL. Surgical treatment and chemotherapy of adult primary liver sarcoma: experiences from a single hospital in China. Dig Surg. 2019; 36:46–52. PMID: 29346784.

16. Boudjema K, Sulpice L, Levi Sandri GB, Meunier B. Portal vein leiomyosarcoma, an unusual cause of jaundice. Dig Liver Dis. 2014; 46:1053–1054. PMID: 25087678.

17. Gaignard E, Bergeat D, Stock N, Robin F, Boudjema K, Sulpice L, et al. Portal vein leiomyosarcoma: a rare case of hepatic hilar tumor with review of the literature. Indian J Cancer. 2019; 56:83–85. PMID: 30950452.

18. Konstantinidis IT, Nota C, Jutric Z, Ituarte P, Chow W, Chu P, et al. Primary liver sarcomas in the modern era: resection or transplantation? J Surg Oncol. 2018; 117:886–891. PMID: 29355969.

19. Wilson SR, Hine AL. Leiomyosarcoma of the portal vein. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987; 149:183–184. PMID: 3495979.

20. Gohrbandt AE, Hansen T, Ell C, Heinrich SS, Lang H. Portal vein leiomyosarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Surg. 2016; 16:60. PMID: 27580598.

21. Sundaresan M, Kelly SB, Benjamin IS, Akosa AB. Primary hepatic vascular leiomyosarcoma of probable portal vein origin. J Clin Pathol. 1990; 43:1036.

22. Zhang XP, Wang K, Li N, Zhong CQ, Wei XB, Cheng YQ, et al. Survival benefit of hepatic resection versus transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2017; 17:902. PMID: 29282010.

23. Ferrozzi F, Bova D, Zangrandi A, Garlaschi G. Primary liver leiomyosarcoma: CT appearance. Abdom Imaging. 1996; 21:157–160. PMID: 8661764.

24. Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009; 49:1017–1044. PMID: 19243014.

25. West J, Card TR. Reduced mortality rates following elective percutaneous liver biopsies. Gastroenterology. 2010; 139:1230–1237. PMID: 20547160.

26. Silva MA, Hegab B, Hyde C, Guo B, Buckels JA, Mirza DF. Needle track seeding following biopsy of liver lesions in the diagnosis of hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2008; 57:1592–1596. PMID: 18669577.

Fig. 1

Leiomyosarcoma of the left portal vein. (A) Computed tomography. (B) Resected specimen. (C) Microscopic examination shows a tumor composed of atypical spindle cells with a fascicular growth pattern. Atypical mitoses were observed. (D) Immunohistochemical staining against alpha-smooth muscle actin was strongly positive.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download