This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Hydatid disease is a zoonotic infection in humans. The disease is endemic in some parts of the world, including Africa, Australia, and Asia, where cattle grazing is common; the disease is spread by an enteric route following the consumption of food contaminated with the eggs of the parasite. Failure to identify this parasite results in delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity to the patient. Upon diagnosis, every possible step should be taken, both surgical and medical, to prevent anaphylactic reactions from the cystic fluid. Postsurgical long-term follow up along with periodical ultrasonography of the liver and computed tomography scan of the abdomen is essential to rule out possible recurrence.

Keywords: Zoonotic infection, Hydatid disease, Pterygomandibular cyst

I. Introduction

Hydatid disease is a zoonotic infection in humans that is caused by the larval hydatid worm of

Echinococcus granulosus. Although infection is mostly commonly observed in the liver (75%), followed by the lungs (5%–15%), the spleen, brain, heart, and kidneys (10%–20%)

1, its incidence in the head and neck region is rare. Occasional cases have been reported in the salivary glands, neck, nasopharynx, maxillary sinus, pterygopalatine or the infra-temporal fossa region

2.

The disease is endemic in some parts of the world, including Africa, Australia, and Asia, where cattle grazing is common; the disease is spread by an enteric route following the consumption of food contaminated with eggs of the parasite

3. The signs and symptoms depend on the site of infection and size of the cyst. Here we present a case of hydatid disease involving the pterygomandibular region.

II. Case Report

A 30-year-old female patient reported to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Amala Institute of Medical Sciences, Thrissur, with a chief complaint of severe pain on the right posterior jaw region and difficulty in opening the mouth over the previous week. On examination, reduced mouth opening (2.5 cm) with severe pericoronal inflammation and swelling in the pterygomandibular and lateral pharyngeal region was observed along with an impacted third molar.(

Fig. 1) A prompt diagnosis of pericoronal infection was confirmed; the patient was put on an antibiotic regimen and the tooth was surgically removed. There was no resolution of the swelling postoperatively and during one month review. An orthopantomogram was taken, which was inconclusive, and followed up with a computed tomographic scan (

Fig. 2), which revealed a well-defined, thin-walled cystic lesion (4.6 cm×2.6 cm×5.3 cm) in the right pterygomandibular space with medial displacement of the parapharyngeal fat. The lesion was displacing the right pterygoid muscles anterolaterally and closely abutting the deep lobe of the right parotid. There was also a notable erosion of the retromolar region.

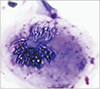

Since the computed tomography (CT) revealed a cystic lesion, fine needle aspiration cytology was conducted. During the procedure, the aspirate yielded clear fluid, but during withdrawal of the needle, the patient exhibited possible signs of a mild anaphylactic reaction, which was promptly managed. Concurrently, the patient was put on dexamethasone 0.5 mg and pheniramine maleate 25 mg for one week. Cytological examination of the aspirate revealed scolices with hooklets, suggestive of a hydatid cystic lesion (

E. granulosus).(

Fig. 3) A course of albendazole was immediately started and then an ultrasonography of the liver and CT scan of the abdomen was performed to rule out other sites of infection.

1. A surgical excision was planned under general anesthesia.

2. The patient was continued on the steroid and antihistamine therapy until surgery to avoid anaphylactic reactions during surgery.

3. Since a plethora of reports have indicated the possibility of anaphylactic reaction caused by the fluid from hydatid lesions, all necessary steps were taken, both surgically and medically, to prevent any untoward incidents.

4. A mandibular midline split access osteotomy was used to gain access to the lesion.

5. The lesion was enucleated

in-toto to prevent spillage of the cystic content.(

Fig. 4)

6. A thorough wound toileting was done to prevent possibilities of recurrence. The course of albendazole was continued for 6 weeks.

7. Postoperative CT of the abdomen followed by ultrasonography of the liver was performed to rule out visceral involvement. The surgery was conducted in 2016 and at the time of writing, the patient still showed no signs of recurrence.

III. Discussion

Hydatid cysts in the maxillofacial region are extremely rare with very few case reports of the disease in the literature. Tongue, parotid and submandibular glands, thyroid gland, maxillary sinuses, nasopharynx, pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossae, and soft tissues in the neck are several sites that have been found to be involved in the faciocervical region

2. The incidence of hydatid cyst is directly proportional to its prevalence in domestic animals. Humans are exposed to eggs of the tapeworm after close contact, after which the larvae pass through the liver and are trapped in pulmonary arterial capillaries, subsequently developing into hydatid cysts. Sometimes these exit the pulmonary arterial capillaries to travel elsewhere in the body

4.

The symptoms of hydatid cysts mimic those of a benign, slow-growing tumor or cyst and vary based on the location and size of the cyst and degree of compression of the surrounding structures

5. Even in hydatid cyst endemic areas, its occurrence in the head and region is rare, which facilitates the dismissal as a possible differential diagnosis in the head and neck region

6. A fine needle aspiration is sufficient for diagnosis and should always be preferred over fine needle biopsy because of the tendency of the cystic content to cause anaphylactic reactions. In addition, the same reason warrants the removal of the entire cystic lesion without breakage.

In-toto removal also helps to prevent development of daughter cysts

7.

PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection, and reaspiration) is an additional non-invasive technique to manage hydatid cysts. A mixture of 95% ethanol, 20% hypertonic saline, and 0.5% silver nitrate has been used as a scolicidal agent and is injected into the cyst before attempting removal

4. The area around the cyst can also be protected from contamination with surgical pads soaked with a scolicidal agent

6.

Untreated conditions will lead to the development of complications, which include anaphylaxis by spontaneous rupture of the cyst, pyogenic abscess in secondarily infected cysts, compression symptoms, and internal organ damage. A pyogenic abscess in the infected cyst was the cause for the chief complaint in the current patient. The antibiotic regimen helped to reduce the infection, but the causative lesion persisted, leading to non-resolution of the lesion. Although these cysts typically appear as a cystic lesion, chances of multiorgan involvement should never be dismissed

8.

Various serological tests like ELISA and hemagglutination tests are there, but are of low sensitivity and specificity with high rates of false positive and negative results. However, once the disease has been diagnosed, these tests do aid in assessing the effectiveness of treatment, recurrence, or possibility of additional cysts. Diagnostic imaging with ultrasonography, CT scan, or magnetic resonance imaging is of high value in locating and evaluating the extent of the cyst

9.

Surgical enucleation of the cyst is the mainstay treatment for hydatid cysts in the maxillofacial region. Extreme caution and care should be taken to prevent rupture of the cyst during removal, which may lead to life-threatening anaphylactic reactions as well as increased chances of recurrence. Injection of 20% hypertonic saline or 5% silver nitrate solution into the cyst can cause inactivation of the daughter cysts before surgery. Additional treatment with albendazole has been recommended by a few researchers to reduce the risk of contamination and to prevent recurrence

6. Multiorgan involvement has been reported in 2% to 40% of cases and thus thorough examination and investigations are required to rule out additional lesions elsewhere in the body.

In conclusion, the current case is one of those instances in which the occupation of the patient or their exposure to such occupational environments plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis of the lesion. Failure to identify this disease entity results in delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity to the patient. Upon diagnosis, every possible step should be taken, both surgical and medical, to prevent anaphylactic reactions from the cystic fluid. Postsurgical long-term follow up along with periodic ultrasonography of the liver and CT scan of the abdomen is essential to rule out possible recurrence.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download