Abstract

Background

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is one of the most common postoperative complications. Despite this, few papers have reported the incidence and independent risk factors associated with PONV in the context of oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS). Therefore, we sought to determine the incidence of PONV, as well as to identify risk factors for the condition in patients who had undergone OMFS under general anesthesia.

Methods

A total of 372 patients' charts were reviewed, and the following potential risk factors for PONV were analyzed: age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, history of PONV and/or motion sickness, duration of anesthesia, amount of blood loss, nasogastric tube insertion and retention and postoperative opioid used. Univariate analysis was performed, and variables with a P-value less than 0.1 were entered into a multiple logistic regression analysis, wherein P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The overall incidence of PONV was 25.26%. In the multiple logistic regression analysis, the following variables were independent predictors of PONV: age < 30 years, history of PONV and/or motion sickness, and anesthesia duration > 4 h. Furthermore, the number of risk factors was proportional to the incidence of PONV.

Conclusions

The incidence of PONV in patients who have undergone OMFS varies from center to center depending on patient characteristics, as well as on anesthetic and surgical practice. Identifying the independent risk factors for PONV will allow physicians to optimize prophylactic, antiemetic regimens.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), which is defined as nausea and/or vomiting occurring within 24 h of surgery, affects between 20% and 30% of patients who have undergone surgery [1]. It is one of the most common complications after surgery, and the most important peri-operative concern for patients [234]. Several previous studies have associated the following risk factors with PONV: patient characteristics (age, sex, smoking status, and history of PONV and/or motion sickness), anesthetic techniques (mask ventilation, volatile anesthetic agents, use of nitrous oxide, and use of opioids), patient hydration, surgery-related factors such as the type and length of surgical procedures, and postoperative factors such as pain level and the use of postoperative opioids [56789]. Nonetheless, few papers have reported the incidence and independent risk factors of PONV in the context of oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS). Specifically, blood swallowing is thought to stimulate PONV in patients who have undergone tonsillectomy [10]. Therefore, it may be that blood in the stomach, or the use of large amounts of irrigating fluid during the intraoral approach, has an emetic effect after OMFS.

Relatedly, we ourselves have postulated that nasogastric (NG) tube insertion and suction reduce the incidence of PONV, and that the smell of blood, blood drainage down the throat, oro-facial swelling, and lip numbness are contributing factors to PONV in patients who have undergone OMFS.

In turn, PONV is a risk factor for airway obstruction, especially in patients with inter-maxillary fixation after OMFS. For this reason, with a view to ultimately reducing the PONV incidence, we performed a retrospective study to determine the incidence of PONV after OMFS under general anesthesia. We also sought to ascertain the risk factors for the condition.

After approval had been acquired from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculties of Dentistry and Pharmacy at Mahidol University, a total of 390 charts of patients who had undergone OMFS under general anesthesia between January 2011 and December 2011 were analyzed retrospectively. This represented all inpatients and outpatients of all ages who had undergone OMFS at our institution during this period.

Patients were excluded if they had (1) undergone extraoral surgery, (2) retained their endotracheal tube for more than 24 h, or (3) incomplete data.

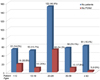

Ultimately, 18 patients were excluded from the study: eight had undergone extraoral surgery, seven had retained their endotracheal tube more than 24 h, and three had incomplete data. Therefore, only 372 patients were enrolled in the study; their ages ranged from 2 to 79 years (mean: 26 years). The patients were divided into five groups according to age: < 10, 11–19, 20–29, 30–39, and > 40 years (Fig. 1).

PONV was defined as either nausea alone or nausea and vomiting, and it was recorded 24 h postoperatively. Potential risk factors associated with PONV were recorded and analyzed.

The following data were collected before surgery: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), history of PONV and/or motion sickness, and smoking status. During surgery, data were collected concerning duration of anesthesia, NG tube insertion, NG tube retention, and blood loss. Data regarding postoperative opioid use were also collected.

Propofol or sevoflurane were used as induction agents, depending on the individual patient's co-operation. Nitrous oxide, sevoflurane, and opioids (morphine, pethidine, or fentanyl) were used to maintain anesthesia in all cases.

Atracurium or cisatracurium was also used; they were reversed at the end of anesthesia. The attending surgeon decided whether to insert the NG tube, and whether to retain or remove it after the operation. A throat pack was placed in every case. Blood loss was calculated using volumetry and gravimetry. Data were coded for computer analysis.

The results were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 13). Continuous variables are reported as means ± standard deviations, while categorical variables are reported as numbers. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the association between the potential risk factors and PONV; in this regard, the χ2 test was used for categorical variables, and the t-test was used for continuous data. Variables with a P-value less than 0.1 were entered into a multivariate analysis, wherein P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

The majority of patients in this study underwent either minor oral surgery (56.6%) or orthognathic surgery (33.4%). Of the 372 patients enrolled in this study, 44.6% (166/372) were male and 55.4% (206/372) were female patients. As shown in Fig. 1, the overall incidence of PONV was 25.3% (94/372).

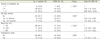

Using univariate analysis, neither sex nor smoking status reached a P-value of 0.1; therefore, they were not evaluated using multivariate analysis. The following variables met the criteria for multivariate analysis: age (Table 1), BMI, history of PONV and/or motion sickness, duration of anesthesia, blood loss, NG tube insertion, NG tube retention, and postoperative opioid used (Tables 2 & 4).

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the patients' age was associated with the incidence of PONV (P < 0.05; Table 3). Specifically, patients below 30 years old showed a significantly higher incidence of PONV than did older patients. In patients younger than 10 years old, the incidence of PONV was almost 20 times higher than that in adults older than 40 years old (P = 0.001, OR = 19.4, 95% CI = 3.58–106.56). Furthermore, the incidence of PONV decreased as age increased.

With regard to BMI, 34.7% (129/372), 54.0% (201/ 372), 8.6% (32/372), and 2.69% (10/372) of the patients were underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese, respectively. The patients were divided into three groups as follows: “underweight”, “normal weight”, and “overweight and obese”. We included overweightness and obesity in the same category because only 10 patients were obese. PONV showed decreased incidence as BMI increased: 33.1%, 21.0%, and 16.7%, in the “underweight”, “normal weight”, and “overweight and obese” groups, respectively (Table 2). However, the relationship between BMI and PONV was not statistically significant (P > 0.05; Table 3).

In the present study, 23.9% (89/372) of the patients had a history of PONV and/or motion sickness. Of these, 33.7% (30/89) had PONV, while only 22.6% (64/283) of the patients without a history of PONV and/or motion sickness had PONV (Table 2). This constituted a significant difference (P = 0.011, OR = 2.26, 95% CI = 1.2– 4.25; Table 3).

The mean duration of anesthesia among all patients was 204.11 ± 105.02 min, while that among patients with PONV (247.61 ± 109.22 min) was significantly higher than that among patients without PONV (189.41 ± 99.54 min; P < 0.01). We divided the duration of anesthesia into three categories: < 2 h, 2–4 h, and > 4 h. The incidences of PONV were 9.6%, 22.2%, and 42.6%, respectively, in these groups. This showed that longer durations of anesthesia were associated with greater incidences of PONV. Indeed, when the duration of anesthesia was longer than 4 h, there was a strong relationship between the duration of anesthesia and PONV (P = 0.001). In patients who had been under anesthesia for more than 4 h, the incidence of PONV was six times higher than in those who had been under anesthesia for less than 2 h (P = 0.01, OR = 6.46, 95% CI = 2.08–20.01; Table 3).

The mean blood loss was 285.32 ± 383.90 ml. The mean blood loss in patients with PONV (380.21 ± 370.61 ml) was significantly higher than that in patients without PONV (253.64 ± 383.67 ml; P < 0.01). We divided blood loss into three categories: ≤ 100 ml, 101–499 ml, and ≥ 500 ml. The incidences of PONV in these groups were 18.5% (37/200), 25.3% (23/91), and 42% (34/81), respectively (Table 4), showing that, with less blood loss, the incidence of PONV was lower. However, multiple logistic regression showed no statistical significance in this regard (P > 0.05; Table 3).

An NG tube was inserted in 32.3% (120/372) of the patients. Among these, 39.2% (47/120) retained the NG tube for least 24 h. We divided the patients into three groups according to the following criteria: those without NG tube insertion, those with NG tube insertion and removal after gastric decompression at the end of surgery, and those who retained NG tube for at least 24 h. The incidence of PONV in these three groups was 20.6% (52/252), 41.1% (30/73), and 25.5% (12/47), respectively (Table 2). The incidence was highest in patients whose NG tube was removed immediately after the operation (Table 4). However, there was no significant difference among the groups (P > 0.05; Table 3).

Opioids were administered after surgery in 13.9% (52/372) of the patients. The incidence of PONV was higher in patients who had received postoperative opioids than in those who had not (34.6% vs. 23.75%). In the multivariate analysis, the relationship between postoperative opioids and PONV was almost significant (P = 0.06, OR = 2.18, 95% CI = 0.97–4.93).

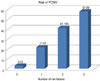

The incidences of PONV in the patients with zero, one, two, or all three of the risk factors that were significant in the multivariate analysis (age under 30 years, history of PONV and/or motion sickness, duration of anesthesia more than 4 h) were 3.03% (2/66), 21.62% (40/185), 41.196% (41/102), and 57.89% (11/19), respectively (Fig. 2).

Nowadays, the development of surgical techniques, discovery of new anesthetics, and introduction of sophisticated monitoring equipment reduce serious life-threatening complications. However, the “big little problem” of PONV still exists; that is, none of the currently used antiemetics can fully prevent PONV [1112]. The incidence of PONV depends on several factors, some of which are related to surgical procedures. Indeed, certain procedures are associated with a particularly high risk of PONV, such as strabismus repair, adeno-tonsillectomy, and laparoscopy. In these operations, the incidence of PONV can be as high as 70% [12].

The overall incidence of PONV in this study was 25.3%. However, this may have been underestimated because nausea without vomiting is difficult to identify in small children. Perrott et al. [13] found that vomiting was the most frequent complication in the recovery room after OMFS under general anesthesia and deep sedation, with an incidence of 0.3%. Meanwhile, Chye et al. [14] reported that, in the context of oral surgery, the incidence of PONV after general anesthesia was 14%, while that after local anesthesia and sedation was 6%. Similarly, Alexander et al. [15] reported a PONV incidence of 11.3% after OMFS without prophylactic antiemetics, while Silva et al. [16] recounted a 40.08% incidence of PONV after orthognathic surgery during the patients' hospital stay. Thus, the reported incidence of PONV after OMFS has varied from center to center, ranging from 0.3% in (Perrott et al. [13]) to 40.8% (Silva et al. [16]). In particular, the incidence was low in the study by Perrott et al. [13] because their population was from an office-based, outpatient setting; some of their patients had been placed under deep sedation, while others underwent general anesthesia. The incidence was high in the study by Silva et al. [16] because these investigators had recruited only patients who had undergone orthognathic surgery, and because they followed the patients for more than 24 h. Thus, the high variability in incidence of PONV results from differences in the kind of surgery performed, the patient population, anesthesia practice, and study design (e.g. follow-up time).

To identify patients who are at high risk of suffering PONV, it is important that surgeons know the risk factors associated with the condition. Routine antiemetic prophylaxis is not required in all patients: patients at low risk of PONV may not benefit at all from such drugs. In fact, the side effects of antiemetics may worsen the condition of low-risk patients and increase their risk of a more difficult recovery.

Silva et al. [16] found that the following risk factors were associated with PONV in orthognathic surgical patients: younger age (particularly 15–25 years old), history of PONV, surgical duration longer than 1 h, maxillary surgery, use of inhalational agent, use of postoperative opioids, and high levels of pain in the post-anesthesia care unit.

Similarly, Alexander et al. [15] found a significant association between PONV and female sex, use of ketamine, duration of surgery, and specific surgical procedure (oncological procedures, temporo-mandibular joint surgery).

In our own study, we found that age was significantly related to PONV. Patients younger than 30 years old demonstrated a significantly higher incidence of PONV than did older patients.

Sinclair et al. [17] reported that a 10-year increase in age decreased the likelihood of PONV by 13%. In the context of orthognathic surgery, Silva et al. [16] found that significantly fewer emetic events occur with increasing age. Furthermore, many previous studies have established that childhood after infancy and younger adulthood are risk factors for PONV [111819].

Although female sex has been the strongest risk factor for PONV in many previous publications [151718192021] and almost all risk scoring systems [5], we did not find any significant correlation between sex and PONV using the χ2 test. We only found that a higher percentage of women than men experienced PONV (27.2% vs. 22.9%). Silva et al. [16] found that the relationship between female sex and PONV was almost significant in orthognathic surgical patients (P = 0.0654).

On a different note, increased BMI is almost always mentioned in the literature as a risk factor for PONV. This is thought to be due to slower gastric emptying times and the accumulation of emetic drugs in fat tissue, although this concept is controversial. For instance, Kranke et al. [22] found no evidence of a positive relationship between BMI and PONV in either their systematic review or their original research. Gan [5] went as far as to declare that obesity has been disproven as a risk factor for PONV. The present study found that the incidence of PONV decreased when BMI increased, but multivariate analysis was unable to detect any positive correlation (Table 3). Silva et al. [16] also found a trend of decreased PONV with increased BMI.

A history of PONV and/or motion sickness is a well-known risk factor for PONV. Most previous studies have shown that patients with prior PONV and/or motion sickness are more likely to have a future emetic episode; our study found the same result. Silva et al. [16] also found that prior PONV was the strongest predictor of PONV. Indeed, a history of PONV and/or motion sickness has been used in all reported PONV risk scoring systems [5].

Many previous studies have found that smokers are less susceptible to PONV than non-smokers; this may be due to an effect on the dopaminergic system [23] or increased hepatic enzymes, especially P450, which breaks down drugs and expedites excretion, thus reducing the emetic effect of anesthetics [24]. Most PONV risk scoring systems include non-smoking status as a well-established risk factor [5]. In the present, only a small number of patients smoked (4.3%); this proportion is not representative of the whole population. The relationship between smoking status and PONV in our study, based on the χ2 test, was not significant. However, the incidence of PONV in smokers was half of that in non-smokers (12.50% and 25.84%, respectively). Likewise, Silva et al. [16] mentioned no relationship between PONV and smoking status.

A number of previous papers have reported an association between the duration of anesthesia and PONV. Sinclair et al. [17] determined that, for every 30-minute increase in duration of anesthesia, there was an increase of 59% in the PONV risk. Thus, a baseline risk of 10% increases to 16% after 30 min of anesthesia. Koivuranta et al. [21] found that an operation time of more than 60 min is a risk factor associated with PONV, probably because of the increased accumulation of emetogenic general anesthetic drugs. Silva et al. [16] found a significant increase in PONV after surgery or more than 2 h. Tabriz et al. [25] reported that, when the operation time was above 165 min, 89% of patients had PONV after orthognathic surgery. The present study found a similar result.

The etiology of emesis involves both central and peripheral stimulation. Blood in the stomach is thought to be one of the strongest peripheral emetogenic stimuli, which stimulate the vomiting center via the gastrointestinal vagal nerve fiber. We hypothesized that more blood loss during the intraoral procedure would increase the chance of blood pooling in the stomach and thus raise the incidence of PONV. Therefore, insertion of an NG tube and gastric evacuation is thought to reduce the incidence of PONV. In the present study, blood loss did not predict the incidence of PONV as well as NG tube insertion and evacuation did. Hence, our routine throat pack, which we use during intraoral approach surgery, may prevent the blood from entering the stomach.

Hovorka et al. [26] and Jones et al. [27] reported that routine suctioning of gastric contents before the conclusion of general anesthesia has no effect on the incidence of PONV. In contrast, Bolton et al. [28] performed a systematic review and meta-analysis, stating that the evidence suggests gastric aspiration prevents PONV in children undergoing tonsillectomy. Nonetheless, it is still not clear whether the NG tube reduces PONV.

Opioid analgesics are used after many kinds of operations. Theoretically, they cause nausea and vomiting by stimulating the chemoreceptor trigger zone, slowing gastrointestinal motility, and prolonging gastric emptying time. A study by Tramer et al. [11] found that around 50% of patients who received opioids as part of patient-controlled analgesia suffer from PONV. Silva et al. [16] reported that 73.93% of their patients used postoperative opioid, and that use of such drugs was correlated with PONV, with an odds ratio of 2.7. Only 13.9% of the patients in this study needed opioids postoperatively because we routinely use non-narcotic analgesics to treat postoperative pain. Multivariate analysis showed no positive relationship between postoperative opioids and PONV in our study.

Evidence from well-designed controlled trials has suggested that prophylactic antiemetics should be administered to patients with a moderate or high risk of PONV [1]. In this regard, a study by Golembiewski et al. [29] suggested that the decision to administer antiemetic prophylaxis should be based on the patient's risk factors. In low-risk patients (zero to one risk factor), no antiemetic is needed; in those with moderate risk (two risk factors), severe risk (three risk factors), and very severe risk (four risk factors), one, two, and three antiemetic prophylaxis drugs should be used.

A number of PONV risk scoring systems have been developed. Apfel et al. [20] developed a simplified risk score consisting of four predictors: female sex, history of PONV and/or motion sickness, non-smoking status, and use of opioids for postoperative analgesia. If none, one, two, three, or four of these risk factors were present, the incidences of PONV were 10%, 21%, 39%, and 78%, respectively. In our own patients, the significant risk factors were as follows: age < 30 years, history of PONV and/or motion sickness, and duration of anesthesia of more than 4 h. The incidence increased as the number of risk factors increased (Fig. 2).

In conclusion, in the context of OMFS, we found that the incidence of PONV and its risk factors varies depending on patient characteristics, as well as on anesthetic and surgical practice. The amount of intraoral blood loss did not predict the incidence of PONV. To ensure that appropriate antiemetic prophylaxis is given, it is important that surgeons know the significant risk factors for PONV.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Number of patients and incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in each group in this study. PONV: Postoperative nausea and vomiting. |

| Fig. 2The number of risk factors and the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting. PONV: Postoperative nausea vomiting |

Table 1

Univariate analysis of postoperative nausea and vomiting by patient age

| Age (years) | P-value | Crude OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| < 10 | < 0.001* | 10.80 (2.98, 39.21) |

| 10–19 | 4.83 (1.25, 18.67) | |

| 20–29 | 10.05 (3.00, 33.64) | |

| 30-39 | 4.20 (1.09, 16.16) | |

| ≥0 | 1 |

Table 2

Univariate analysis of postoperative nausea and vomiting by patient body mass index, history of postoperative nausea and vomiting and/or motion sickness, and smoking status

Table 3

Multiple logistic regression analysis of postoperative nausea and vomiting and its possible risk factors

Table 4

Univariate analysis of postoperative nausea and vomiting by intra-operative and postoperative factors

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the staff and dental assistants, including our colleagues at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, and in the operating room of the Faculty of Dentistry at Mahidol University.

References

1. McCracken G, Houston P, Lefebvre G. Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada. Guideline for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008; 30:600–607.

2. Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg. 1999; 89:652–658.

3. Eberhart L, Morin AM, Wulf H, Geldner G. Patient preferences for immediate postoperative recovery. Br J Anaesth. 2002; 89:760–761.

4. Gan T, Sloan F, Dear GL, El-Moalem HE, Lubarsky DA. How much are patients willing to pay to avoid postoperative nausea and vomiting? Anesth Analg. 2001; 92:393–400.

6. Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Eubanks S, et al. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2003; 97:62–71.

7. Gan TJ, Meyer TA, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Habib AS, et al. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2007; 105:1615–1628.

8. Islam S, Jain PN. Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV): A review article. Indian J Anaesth. 2004; 48:253–258.

9. Rüsch D, Eberhart LHJ, Wallenborn J, Kranke P. Nausea and vomiting after surgery under general anesthesia—An evidence-based review concerning risk assessment, prevention, and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010; 107:733–741.

10. Roberts RG, Jones RM. Paediatric tonsillectomy and PONV-Big little problem remained big! Anaesthesia. 2002; 57:619–620.

11. Tramer MR. A rational approach to the control of postoperative nausea and vomiting: evidence from systematic reviews. Part I. Efficacy and harm of antiemetic interventions, and methodological issues. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001; 45:4–13.

12. Apfel CC, Kortilla K, Abdalla M, Kerger H, Turan A, Vedder I, et al. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:2441–2451.

13. Perrott DH, Yuen JP, Anderson RV, Dodson TB. Office-Based Ambulatory Anesthesia: Outcomes of Clinical Practice of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 61:983–995.

14. Chye EPY, Young IG, Osborne GA, Rudkin GE. Outcomes after same-day oral surgery: A review of 1,180 cases at a major teaching hospital. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993; 51:846–849.

15. Alexander M, Krishnan B, Yuvraj V. Prophylactic antiemetics in oral and maxillofacial surgery- a requiem? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67:1873–1877.

16. Silva AC, O'Ryan F, Poor DB. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) after orthognathic surgery: a retrospective study and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:1385–1397.

17. Sinclair DR, Chung F, Mezei G. Can postoperative nausea and vomiting be predicted? Anesthesiology. 1999; 91:109–118.

18. Van den Bosch JE, Moons KG, Bonsel GJ, Kalkman CJ. Does measurement of preoperative anxiety have added value for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting? Anesth Analg. 2005; 100:1525–1532.

19. Eberhart LH, Geldner G, Kranke P, Morin AM, Schäuffelen A, Treiber H, et al. The development and validation of a risk score to predict the probability of postoperative vomiting in pediatric patients. Anesth Analg. 2004; 99:1630–1637.

20. Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. 1999; 91:693–700.

21. Koivuranta M, Laara E, Snare L, Alahuhta S. A survey of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 1997; 52:443–449.

22. Kranke P, Apfel CC, Papenfuss T, Rauch S, Löbmann U, Rübsam B, et al. An increased body mass index is no risk factor for postoperative nausea and vomiting. A systematic review and results of original data. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001; 45:160–166.

23. Apfel CC, Rauch S, Goepfert C, Sefrin P, Rower N. The impact of smoking on postoperative vomiting. Anesthesiology. 1997; 87:A25.

24. Chimbira W, Sweeney BP. The effect of smoking on postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 2000; 55:540–544.

25. Tabrizi R, Eftekharian HR, Langner NJ, Ozkan BT. Comparison of the effect of 2 hypotensive anesthetic techniques on early recovery complications after orthognathic surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2012; 23:e203–e205.

26. Hovorka J, Korttila K, Erkola O. Gastric aspiration at the end of anesthesia does not decrease post operative nausea and vomiting. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1990; 18:58–61.

27. Jones JE, Glasgold R, Gomillion MC. Efficacy of gastric aspiration in reducing posttonsillectomy vomiting. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001; 127:980–984.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download