This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

We aimed to confirm the long-term effect of patellar nonresurfacing (patellar decompression) in preventing anterior knee pain after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and to investigate the possible complications.

Methods

Among patients who underwent primary TKA after being diagnosed as having advanced osteoarthritis (Kellgren-Lawrence grade 4) at our institution from January 2004 to December 2010, 121 patients who were followed up for more than 7 years were included in this study. Patients who underwent TKA with and without patellar decompression were classified as the study group and control group, respectively. A clinical knee rating score was used to compare the postoperative clinical outcomes between groups. To identify complications after patellar decompression, simple radiographs (weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral views, patella in 30° and 45° axial views, and whole scanogram) were taken during follow-up.

Results

There were no complications such as patellar fracture, osteonecrosis, and subluxation. At 2 years after surgery, the prevalence of anterior knee pain was 12.7% and 18.0% in the study group and control group, respectively (p = 0.42), and the number of patients with patellofemoral osteoarthritis grade II or over was lower in the study group (p = 0.03). At 7 years after surgery, the prevalence of anterior knee pain was 18.3% and 24.0% in the study group and control group, respectively (p = 0.45), and there was no statistically significant intergroup difference in the number of patients with patellofemoral osteoarthritis grade II or over (p = 0.11).

Conclusions

Patellar nonresurfacing TKA reduces anterior knee pain in the early postoperative period. The procedure can be considered a relatively safe option with fewer complications; however, its effectiveness appears to decrease over time.

Go to :

Keywords: Knee, Osteoarthritis, Total knee replacement arthroplasty, Patellar decompression

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has been shown to be a successful procedure for treating advanced knee joint arthritis. Despite advances in techniques and implants, anterior knee pain is one of the most common problems after TKA. In the literature, anterior knee pain has been reported in 8% to 50% of cases after TKA.

1234) Thus, after periprosthetic infection, patellofemoral joint problems are the second most common cause of revision TKA.

567)

The causes of anterior knee pain can be divided into functional (muscle imbalance and dynamic valgus), structural (chondromalacia of the patella), mechanical (incorrect positioning of prosthetic components and aseptic loosening), and pathophysiologic (patellar hypertension syndrome).

89101112) Patellar resurfacing has been attempted to solve the structural problem, but the effect remains controversial.

131415)

The increase in intraosseous pressure of the distal femur causes anterior knee pain.

12) Several studies have reported on the pathophysiologic factors of anterior knee pain.

1617) Since the introduction of patellar hypertension syndrome, new treatment concepts such as intraosseous drilling (patellar decompression) have been suggested.

16) Several studies have reported on the short-term effects of patellar decompression in anterior knee pain.

916) However, there are a limited number of studies on anterior knee pain after TKA with patellar hypertension. In this study, we aimed to confirm through long-term follow-up the effect of patellar decompression in preventing anterior knee pain after TKA without resurfacing and to investigate the possible complications.

METHODS

Patients

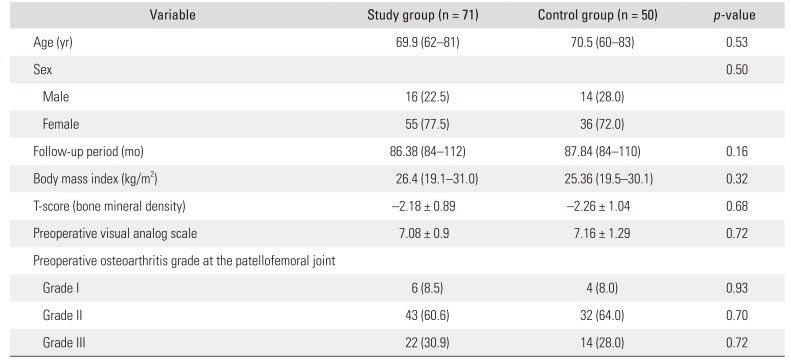

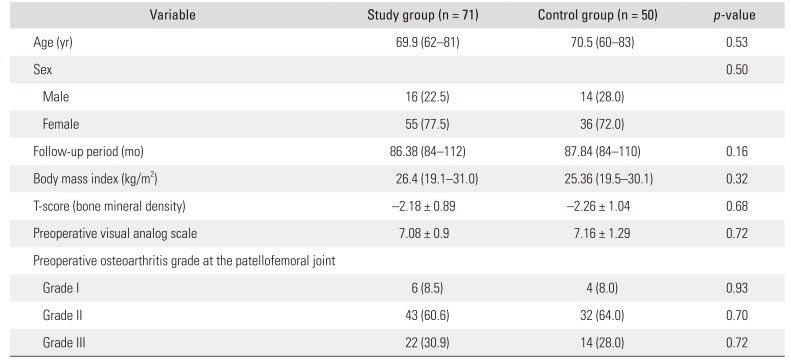

The study was conducted retrospectively by reviewing plain radiographs, medical records, and patient interviews. We conducted this study in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The design and protocol of this retrospective study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kosin University Gospel Hospital (IRB No. 2019-04-020). Written informed consents were waived since this study was conducted retrospectively. Among patients who underwent primary TKA (Duracon; Howmedica, Rutherford, NJ, USA) after diagnosis of advanced osteoarthritis (Kellgren-Lawrence grade 4) at our institution from January 2004 to December 2010, 121 patients who were followed up for more than 7 years were included in this study. The exclusion criteria were history of systemic inflammatory disease, any disease causing lower extremity pain (e.g., herniated disc, spinal stenosis, and arteriosclerosis obliterans), and/or signs or symptoms of infection during follow-up. Patients who underwent TKA with and without patellar decompression were classified as the study group and control group, respectively. Patient data are shown in

Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic Data

|

Variable |

Study group (n = 71) |

Control group (n = 50) |

p-value |

|

Age (yr) |

69.9 (62–81) |

70.5 (60–83) |

0.53 |

|

Sex |

|

|

0.50 |

|

Male |

16 (22.5) |

14 (28.0) |

|

|

Female |

55 (77.5) |

36 (72.0) |

|

|

Follow-up period (mo) |

86.38 (84–112) |

87.84 (84–110) |

0.16 |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

26.4 (19.1–31.0) |

25.36 (19.5–30.1) |

0.32 |

|

T-score (bone mineral density) |

−2.18 ± 0.89 |

−2.26 ± 1.04 |

0.68 |

|

Preoperative visual analog scale |

7.08 ± 0.9 |

7.16 ± 1.29 |

0.72 |

|

Preoperative osteoarthritis grade at the patellofemoral joint |

|

|

|

|

Grade I |

6 (8.5) |

4 (8.0) |

0.93 |

|

Grade II |

43 (60.6) |

32 (64.0) |

0.70 |

|

Grade III |

22 (30.9) |

14 (28.0) |

0.72 |

Surgical Procedure

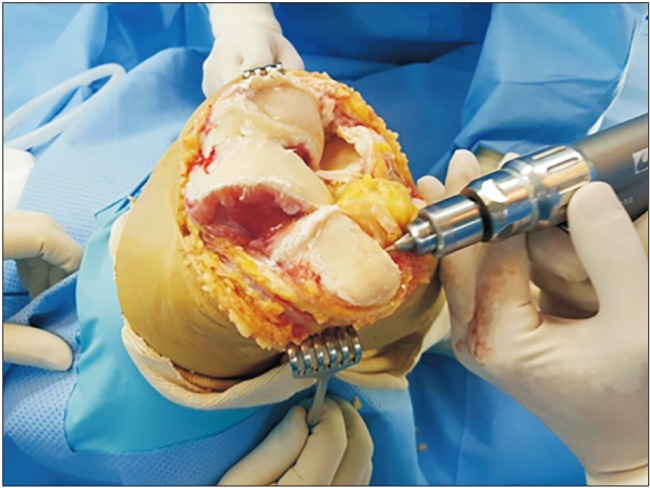

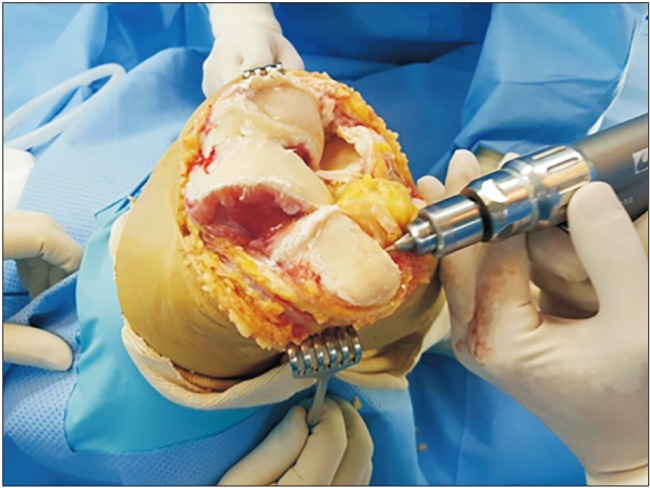

All operations were done by a single surgeon (JS). All surgical approaches were performed with a midline skin incision and mid-vastus approach (

Fig. 1). The desired angle was 8° valgus. A posterior cruciate ligament–retaining cemented implant was used in all patients (Duracon, Howmedica). Patellar resurfacing was not performed in any cases. In the study group, we first performed osteophyte removal of the patellar rim. Then, we used a 3.5-mm drill to drill the patella via the fat pad under tissue protection in a parallel pattern (

Fig. 2). Four to six holes were drilled parallel to the leg axis in the patella (

Fig. 3).

| Fig. 1Before patellar decompression, severe osteophytes and cartilage defect were identified.

|

| Fig. 2We used a 3.5-mm drill to drill the patella via the fat pad under tissue protection in a parallel pattern.

|

| Fig. 3Patellar decompression and osteophyte removal were performed.

|

Evaluation

We conducted a patient interview and used a simple clinical anterior knee pain rating to assess anterior knee pain.

9) The interview included following questions on the presence of pain, limitation of activity, and the need for additional surgery: (1) does anterior knee pain occur when rising from the chair? (2) Does anterior knee pain occur when ascending or descending the stairs? (3) Does anterior knee pain occur when squatting? (4) Does anterior knee pain occur when resting? (5) Is it difficult to fall asleep due to anterior knee pain? A clinical knee rating score was used to compare postoperative clinical outcomes. To identify complications after patellar decompression, simple radiographs (weight-bearing anteroposterior, lateral view, patella 30° and 45° axial views, and whole scanogram) were taken during follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS ver. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Paired sample t-tests were used to compare preoperative and postoperative rates of the clinical knee rating score. Pearson's chi-square test was used to compare the anterior knee pain of the study and control groups. Student t-test was used to compare the demographic differences of the study and controls. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Go to :

RESULTS

A total of 121 patients were followed up for more than 7 years after TKA. There were no statistically significant differences in demographics between the study and control groups (

Table 1). Postoperative radiographs were assessed for knee alignment, patellar tilt, and patellar height, and no significant differences were found between the groups. Follow-up radiography was performed every year until the last follow-up. There were no complications such as patellar fracture, osteonecrosis, and subluxation.

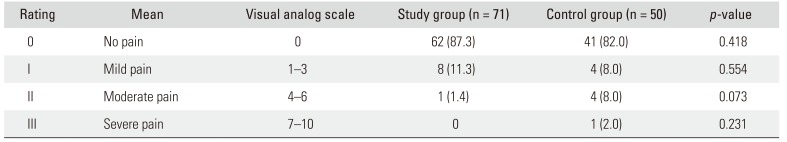

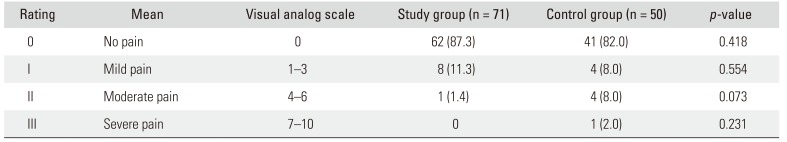

The prevalence of anterior knee pain was 12.7% in the study group and 18.0% in the control group at 2 years after surgery (

Table 2), showing no statistically significant differences between groups (

p = 0.42). However, the number of patients with patellofemoral osteoarthritis grade II or over was significantly lower in the study group (

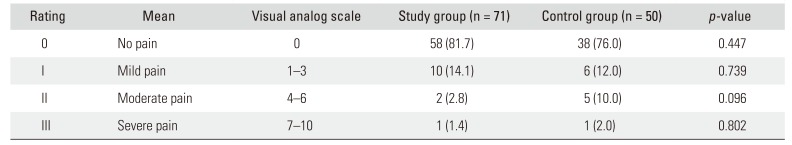

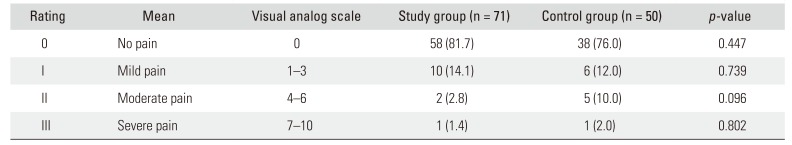

p = 0.03). The prevalence of anterior knee pain was 18.3% in the study group and 24% in the control group at 7 years after surgery (

Table 3), showing no statistically significant differences between groups (

p = 0.45). The number of patients with patellofemoral osteoarthritis grade II or over was not statistically significantly different between groups at 7 years after surgery (

p = 0.11).

Table 2

Anterior Knee Pain Rating at 2 Years after Surgery

|

Rating |

Mean |

Visual analog scale |

Study group (n = 71) |

Control group (n = 50) |

p-value |

|

0 |

No pain |

0 |

62 (87.3) |

41 (82.0) |

0.418 |

|

I |

Mild pain |

1–3 |

8 (11.3) |

4 (8.0) |

0.554 |

|

II |

Moderate pain |

4–6 |

1 (1.4) |

4 (8.0) |

0.073 |

|

III |

Severe pain |

7–10 |

0 |

1 (2.0) |

0.231 |

Table 3

Anterior Knee Pain Rating at 7 Years after Surgery

|

Rating |

Mean |

Visual analog scale |

Study group (n = 71) |

Control group (n = 50) |

p-value |

|

0 |

No pain |

0 |

58 (81.7) |

38 (76.0) |

0.447 |

|

I |

Mild pain |

1–3 |

10 (14.1) |

6 (12.0) |

0.739 |

|

II |

Moderate pain |

4–6 |

2 (2.8) |

5 (10.0) |

0.096 |

|

III |

Severe pain |

7–10 |

1 (1.4) |

1 (2.0) |

0.802 |

The mean knee score improved from 43.25 points (range, 5 to 75 points) to 89.04 points (range, 70 to 100 points) in the study group and from 44.62 points (range, 10 to 75 points) to 85.24 points (range, 65 to 95 points) in the control group. The mean knee score was higher in the study group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.18). The postoperative mean knee function score was 76.42 points (range, 25 to 100 points) in the study group and 73.53 points (range, 20 to 100 points) in the control group, showing no statistically significant difference (p = 0.33).

Go to :

DISCUSSION

The principle finding of this study is that patellar decompression performed by using a 3.5-mm drill could reduce postoperative anterior knee pain in the early postoperative period, but the effect decreased in the long-term follow-up. Anterior knee pain after TKA is one of the most common complications. Many studies have focused on the structural characteristics to prevent this complication. Surgical methods suggested in these studies include patellar osteotomy, distal realignment procedure, and patellar resurfacing, but their effect remains controversial.

131415) A previous study conducted at our hospital introduced the concept of increased intraosseous pressure and patellar hypertension, which have been reported as one of the causes of anterior knee pain.

9) Some studies have reported that an impaired venous drainage induces intraosseous hypertension.

1617) Schneider et al.

16) reported that if the venous pathway of the patella is impaired, patellar drilling leads to the immediate reduction of intraosseous pressure and pain relief.

In this study, we focused on the pathophysiologic factors of anterior knee pain and suggested patellar decompression as a solution. If anterior knee pain arises from patellar hypertension after TKA, it can be solved by patellar decompression. In the literature, anterior knee pain has been reported in 8%–50% of cases after TKA.

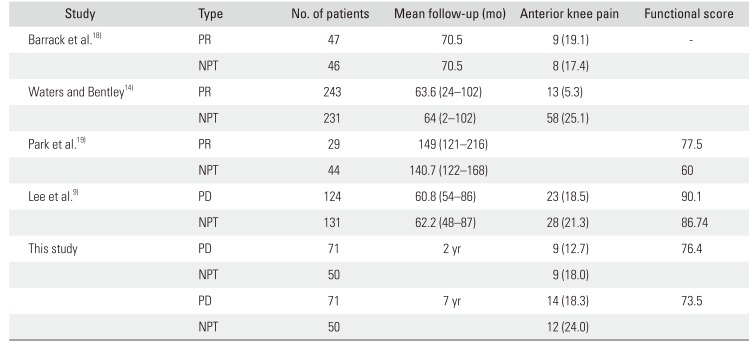

1234) Patellar resurfacing is the most commonly used method, but the results are controversial and can lead to complications such as patellar replacement component wear, loosening, fractures, and osteonecrosis (

Table 4).

9141819) In this study, there were no complications such as fracture or osteonecrosis after patellar decompression during follow-up, which is consistent with the findings of previous reports on patellar decompression.

9)

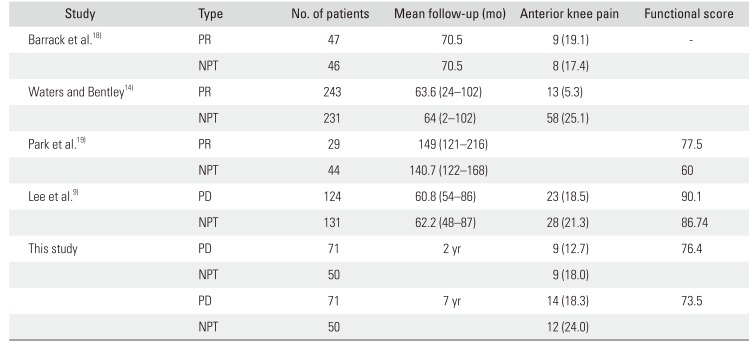

Table 4

Publications on Anterior Knee Pain after Total Knee Arthroplasty

|

Study |

Type |

No. of patients |

Mean follow-up (mo) |

Anterior knee pain |

Functional score |

|

Barrack et al.18)

|

PR |

47 |

70.5 |

9 (19.1) |

- |

|

NPT |

46 |

70.5 |

8 (17.4) |

|

|

Waters and Bentley14)

|

PR |

243 |

63.6 (24–102) |

13 (5.3) |

|

|

NPT |

231 |

64 (2–102) |

58 (25.1) |

|

|

Park et al.19)

|

PR |

29 |

149 (121–216) |

|

77.5 |

|

NPT |

44 |

140.7 (122–168) |

|

60 |

|

Lee et al.9)

|

PD |

124 |

60.8 (54–86) |

23 (18.5) |

90.1 |

|

NPT |

131 |

62.2 (48–87) |

28 (21.3) |

86.74 |

|

This study |

PD |

71 |

2 yr |

9 (12.7) |

76.4 |

|

NPT |

50 |

|

9 (18.0) |

|

|

PD |

71 |

7 yr |

14 (18.3) |

73.5 |

|

NPT |

50 |

|

12 (24.0) |

|

The prevalence of anterior knee pain at two years after surgery was similar to that reported by Lee et al.

9) In both studies, compared to the group without patellar decompression, the group with patellar decompression had a greater number of patients with less than moderate pain at 2 years after surgery. However, in our study, there was no statistically significant intergroup difference in anterior knee pain at 7 years' follow-up. This is different from the result of Lee et al.

9) The reason for this difference may be attributable to the fact that the average follow-up period of Lee's study was approximately 60 months. On the basis of our 7-year follow-up results, we think that the effect of patellar decompression is maintained for up to 5 years, but the effect decreases thereafter.

This study has some limitations. First, there are few studies on the effect of patellar decompression; thus, comparison of the results was limited. However, patellar decompression is considered an effective technique in reducing anterior knee pain because it can be performed by drilling during primary TKA without the need for additional procedures. Second, because the intraosseous pressure was not directly measured in this study, there were some limitations in demonstrating the effectiveness of patellar decompression.

Patellar nonresurfacing in TKA can be performed during primary TKA without an additional incision. This procedure can reduce anterior knee pain in the early postoperative period. In conclusion, patellar nonresurfacing TKA can be a relatively safe and simple procedure with fewer complications, but its effect on relief of anterior knee pain appears to decrease in the long term.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download